Consciousness, Indian Psychology and Yoga

Book Specification

| Item Code: | NAF974 |

| Author: | D.P. Chattopadhyaya |

| Publisher: | Centre for Studies in Civilizations |

| Language: | English |

| Edition: | 2012 |

| ISBN: | 9788187586173 |

| Pages: | 533 |

| Cover: | Hardcover |

| Other Details | 11.5 inch X 9.0 inch |

| Weight | 1.60 kg |

Book Description

The volumes of the PROJECT OF THE HISTORY OF INDIAN SCIENCE, PHILOSOPHY AND CULTURE [PHISPC] aim at discovering the main aspects of India’s heritage and present them in an interrelated way. These volumes, in spite of their unitary look, recognize the difference between the areas of material civilization and those of ideational culture. The Project is not being executed by a single group of thinkers and writers who are methodologically uniform or ideologically identical in their commitments. In fact, contributions are made by different scholars with different ideological persuasions and methodological approaches. The project is marked by what may be called ‘methodological pluralism’. In spite of its primary historical character, this Project, both in its conceptualization and execution, has been shaped by many scholars drawn from different disciplines. It is for the first time that an endeavour of such a unique and comprehensive character has been undertaken to study critically a major world civilization like India.

CONSCIOUSESS, INDIAN PSYCHOLOGY AND YOGA is one of a set of four volumes purported to launch the sub-project CONSCIOUSNESS, SCIENCE, SOCIETY, VALUE AND YOGA [CONSSAVY], which is an extension of the PHISPC. Devoted to the exploration of consciousness, this volume is part of an on-going effort to bring the Indic tradition and the social science closer together. Its focus is on three major contributions: a deep and many-faceted understanding of consciousness, a well-worked out methodology to arrive at reliable knowledge of the subject domain, and a variety of effective methods to transcend and transform human nature. Just as western science has used physical technology to increase our knowledge and power in the physical domain, so the Indic traditions has used yoga to create an immense wealth of insight and wisdom in the psychological domain. The five section of this book deal with: the central role of consciousness in Indian psychology; different paths of Yoga; the coming together of Indian and Western systems of psychological thought; Indian approaches to core issues of theoretical psychology; and finally, Indian contributions to various aspects of applied psychology, which range from physical health to sustainable development, management and psychotherapy.

D.P. CHATTOPADHYAYA, M.A., LL.B., Ph.D. (Calcutta and London School of Economics), D. Litt., (Honoris Causa), studied, researched on Law, philosophy and history and taught at various Universities in India, Asia, Europe and USA from 1954 to 1994. Founder-Chairman of the Indian Council of Philosophical Research (1981-1990) and President-cum-Chairman of the Indian Institute of Advanced Study, Shimla (1984-1991), Chattopadhyaya is currently the Project Director of the multidisciplinary ninety-six volume Project of History of Indian Science, Philosophy and Culture (PHISPC) and Chairman of the Centre for Studies in Civilizations (CSC). Among his 37 publications, authored 19 and edited or co-edited 18, are Individuals and Societies (1967); Societies Individuals and Worlds (1976); Sri Aurobindo and Karl Marx (1988); Anthropology and Historiography of Science (1990); Induction, Probability and Skepticism (1991); Sociology, ideology and Utopia (1997); Societies, Cultures and Ideologies (2000); Interdisciplinary Studies in Science, Phenomenlogy and Other Essays (2003); Philosophical Consciousness Background (2004); Self, Society and Science: Theoretical and Historical Perspectives (2004); Religion, Philosophy and Science (2006); Aesthetic Theories and Forms in Indian Tradition (2008) and Love, Life and Death (2010). He has also held high public offices, namely, of Union cabinet minister and state governor. He is a Life Member of the Russian Academy of Sciences and a Member of the International Institute of Philosophy, Paris. He was awarded Padma Bhushan in 1998 and Padmavibhushan in 2009 by the Government of India.

KIREET JOSHI, Education Advisor to the Chief Minister of Gujarat, was earlier Registrar of Sri Aurobindo International Centre of Education, Pondicherry (till 1976), Education Adviser to Government of India (1976-77) and Special Secretary in the Union Ministry of Human Resource Development (1983-88). He was also Chairman of Indian Council of Philosophical Research for two terms (2000-2006), Chairman of Auroville Foundation (1999-2004), Member-Secretary of Rashtriya Veda Vidya Pratishthan (1987-1993) and Vice-Chairman of the UNESCO Institute of Education, hamburg (1987-1989). He is currently staying in Sri Aurobindo Ashram, Puducherry. Among his 48 publications, 28 authored, 17 edited and 3 compiled, are A National Agenda for Education; Education for Character Development; Education for Tomorrow; Education at Crossroads; Sri Aurobindo and Integral Yoga; Ssri Aurobindo and the; Mother, Landmarks of Hinduism; The Veda and Indian Culture, Glimpses of Vedic Literrature, The Portals of Vedic Knowledge, Bhagavad Gita and Contemporary Crisis; Philosophy and Yoga of Sri Aurobindo and Other Essays; A Philosophy of Evolution for the Contemporary Man; Consciousness, Indian Psychology and Yoga; The Aim of Life, The Good Teacher and the Good Pupil; Mystery and Excellence of Human Body, Gods and the World; Nala and Damayanto; Alexander the Great; Siege of Troy, Homer and the Iliad; Sri Aurobindo and Ilion; Catherine the Great, Parvati’s Tapasya; Sri Krishna in Vrindavan; Socrates, Nachiketas; Sri Rama; Child, Teacher and Teacher Education and Philosophy of Supermind and Contemporary Crisis.

MATTHIJS CORNELISSEN, member of the editorial team overseeing the publication of The Complete Words of Sri Aurobindo, teaches Integral Psychology at the Sri Aurobindo International Centre of Education, Pondicherry. A qualified physician, he came to India in 1976 to study the confluence of Yoga and psychotherapy. Together with Neeltje Huppes he founded in 1981 Mirambika, an experimental teacher training college in New Delhi. His recent publications include Consciousness and Its Transformation and papers like Towards an Integral Epistemology of Consciousness and The Need for the Indian Tradition.

The present volume is part of an ongoing effort to bring the Indian tradition and science closer together. That the Indian civilization has much to contribute to the emerging global culture in terms of arts, dance, music and spirituality, is widely recognised. What is much less well appreciated is how much the humanities and social sciences could gain from a greater familiarity with insights derived from Indian philosophy and yoga. The core of what the Indian tradition can contribute in these areas consists of three closely related elements: a deep and many-faceted understanding of consciousness, a well-worked out methodology to arrive at reliable knowledge of the subjective domain, and methods to change our own psychological nature. Just as western science has made its phenomenal progress over the last few centuries with the help of physical technology, so the Indian tradition has created its immense wealth of psychological insight with the help of yoga.

Yoga in its essence is the path that leads to union with the Divine. There are many different ways to describe this ultimate aim of yoga, and many different paths to arrive there. Together these many different paths have explored the entire range of what human nature is capable of, right from the lowest abysms of ignorance to the highest peaks of wisdom. In the process, over many millennia of collective labour, the Indian tradition has become incomparably rich in psychological insight about every aspect of human nature and consciousness.

In terms of theory it is not easy to bring the paths of yoga and science together, as their philosophical starting points and methods of enquiry are entirely different. The issues at stake are rather complex, but we could perhaps formulate the starting points of the two knowledge systems as follows: mainstream science starts from the physical world, and presumes that our consciousness and inner states are generated by a combination of physical and environmental factors. The dominant trend in the Indian tradition is to begin with consciousness, to look even at the physical world as a manifestation of consciousness, and to presume that it is our inner being, which is responsible for creating our outer circumstances. Things are not that simple of course and both lines of thought are embedded in complex worlds of ideas in which all elements are interdependent, but roughly these seem to be the two directions in which knowledge is sought.

In terms of method, western psychology tries to be as objective as possible, and relies on observations that can be made by all. To get over the obvious limitations this entails, it calls in the help of large population surveys, physical instruments, and sophisticated mathematical analysis. The Indian approach is essentially subjective. To get over the obvious difficulties this entails, it relies on our ability to perfect our inner instrument of knowledge, hte antahkarana. As this is difficult and cannot be done by all, the Indian tradition relies for its knowledge base on the findings of a few, highly evolved or “realised” sages, somewhat in the same manner as physics depends on those few who have exceptional mathematical skills.

While it is difficult to bring these two knowledge systems together theoretically, it is much easier to do so in the applied field. To introduce elements of yoga into therapy, education or management, for example, is fairly straightforward. This might hint at the possibility that the underlying reality, which both approaches try to grasp in their opposing theoretical networks, rests somewhere in between.

There are five sections in the present volume. The first section contains four papers about consciousness. The first describes yoga as a practical technology of consciousness leading to insight, siddhis and finally liberation and transformation. The second discusses Sri Aurobindo’s concept of evolution of consciousness, in which the nature of spirituality itself evolves over time. The third is an overview of the relation between western and Indian psychology and the role of consciousness in both. The last gives a detailed description of the Vedantic view culminating in a discussion of the role of rasa and ananda in art.

The second section deals with various methods and experience of Yoga, right from the Vedas to modern times. The expositions given here are only illustrative, since it is impossible in this volume to attempt a comprehensive account. What is presented here gives a broad coverage, and the authors are all prominent authorities in their respective fields. Together they give a good impression of the tremendous richness of insight available within the Indian tradition.

The third section deals with the difficulties encountered in bringing the western and Indian traditions together. As such several of the papers in this section have a distinct autobiographical element. The six papers in this section approach the issue from a number of entirely different angles. The first looks at the position of western and Indian approaches on a series of conceptual dichotomies, the second at the (in) ability of different psychological schools to give meaning to life, the third to the origin and role of relativism, the fourth at the importance of personal growth in the teaching of psychology, and the last two at the demands of the future.

Section four contains a number of papers on some core issues in theoretical psychology. There are four chapters on different aspects of knowledge and mind, followed by one on emotion (focusing on Bharata’s treatment of the concepts of rasa and bhava), one on different personality typologies, and one on the structure of the personality. The last paper covers the extremely important field of developmental psychology, which is one of the areas where western and Indian approaches can perhaps make the most useful contributions to each other.

Section five brings nine interesting papers together in the field of applied psychology. The first one deals with the effect of the yogic way of life on happiness and physical health. The second is a touching description of how ideas from the Indian tradition have helped to develop a programme of sustainable development in the Himalayas. The next two deal with the use of Indian psychology in organisational behaviour, one in the management of an extraordinary private eye care organisation in South India, and the other in a nationalised rural bank in West Bengal. After this there are four papers dealing with different aspects of psychotherapy: the first is centred round the concept of sattvavajaya, the second on the concept of sahya as a core quality of psychotherapist, and the third on grhastha, as used in family therapy. The fourth is on the use of a new form of integral psychotherapy to increase the general well-being of cancer patients. The last chapter provides a light note on the development of “spiritual intelligence”.

We would like to express our profound gratitude to Mr. A.K. Sen Gupta and to Ms. Lynn Crawford for their untiring labours and encouragement, without which this book would not have materialized.

The spectrum of the Indian views on consciousness is very wide and varied. There is no single view in this country, marked by the variety of a vast continent, which can rightly be claimed to be its paradigmatic view. That the body is not consciousness seems to be universally acknowledged. Also it generally recognized that the human body is different from other living and non-living bodies. What distinguishes, at least apparently, a living body from a non-living body deserves and has received very many careful considerations, leading to different conclusions.

While the pro-materialists like the Carvaka and Lokayata sects emphasize the primacy of matter-in-motion, the defenders of the primacy of consciousness affirm that all seemingly unconscious or non-conscious things are consciousness in essence. In between pro-reductionist materialism and pro-reductionist immaterialism or cetanavada there are several other notable views, for example, those of the Samkhya-Yoga, Advaita Vedanta and Buddhism. Both affirmation and rejection of consciousness are sought to be buttressed by various types of reasoning, from logical to analogical and rhetorical.

It is interesting to note that paranormal forms of experience have drawn deep attention and elaborate discussion, supportive or refutive, in all types of Indian thinkers, pre-systematic and systematic, orthodox and heterodox.

Careful distinction has been drawn between sense-linked mentality and disembodied spirituality. Questions like (i) whether consciousness obeys the law of locality, and (ii) whether non-locality, implying universality, is its essence, have been discussed at length.

In the Indian systems of thought and sadhana, one finds that Yoga occupies a very important place. In almost all systems, yoga figures in some way or other. The recognized forms of Yoga are numerous. The practice of Yoga is claimed to have a profound transformative influence on the human body and mind and even on collective entities like community and society. The whole human species, says Sri Aurobindo, can be and is being upwardly transformed by the power and light of Yoga.

A majority of the articles in the current Volume are based on presentations made in the seminar on “Yoga and Indian Approaches to Psychology” held in Pondicherry in September 2002. The seminar was sponsored by the Indian Council of Philosophical Research (ICPR). Five articles of the Volume are based on presentations made in another seminar on “Yoga and Consciousness”, held in New Delhi in December 2003. The seminar was sponsored by the Indian Institute of Advanced Studies (IIAS), Shimla. I am grateful to both ICPR and IIAs for making available the proceedings of their seminars for a PHISPC Volume. The Volume also contains three articles, of which two by the editors, which were not presented in the above seminars.

The rich contributions of Indian thinkers and sadhakas to psychology and other kinds of consciousness studies have been imaginatively and rigorously brought out in this well-edited Volume. The editors, Professor Kireet Joshi and Dr. Matthijs Cornelissen, and their collaborators deserve our heartfelt thanks and gratitude. I hope this publication will open up a new horizon for study of psychology in India.

It is understandable that man, shaped by Nature, would like to know Nature. The human ways of knowing Nature are evidently diverse, theoretical and practical, scientific and technological, artistic and spiritual. This diversity has, on scrutiny, been found to be neither exhaustive nor exclusive. The complexity of physical nature, life world and, particularly, human mind is so enormous that it is futile to follow a single method for comprehending all the aspects of the world in which we are situated.

One need not feel bewildered by the variety and complexity of worldly phenomena. After all, both from traditional wisdom and our daily experience, we know that our own nature is not quite alien to the structure of the world. Positively speaking, the elements and forces that are out there in the world are also present in our body-mind complex, enabling us to adjust ourselves to our environment. Not only the natural conditions but also the social conditions of life have instructive similarities between them. This is not to underrate in any way the difference between the human ways of life all over the world. It is partly due to the variation in climatic conditions and partly due to the distinctness of production-related tradition, history and culture.

Three broad approaches are discernible in the works on historiography of civilization, comprising science and technology, art and architecture, social sciences and institutions. Firstly, some writers are primarily interested in discovering the general laws which govern all civilizations spread over different continents. They tend to underplay what they call the noisy local events of the external world and peculiarities of different languages, literatures and histories. Their accent is on the unity of Nature, the unity of science and the unity of mankind. The second group of writers, unlike the generalist or transcendentalist ones, attach primary importance to the distinctiveness of every culture. To these writers human freedom and creativity are extremely important and basic in character. Social institutions and the cultural articulations of human consciousness, they argue, are bound to be expressive of the concerned people’s consciousness. By implication they tend to reject concepts like archetypal consciousness, universal mind and providential history. There is a third group of writers who offer a composite picture of civilizations, drawing elements both from their local as well as common characteristics. Every culture has its local roots and peculiarities. At the same time, it is pointed out that due to demographic migration and immigration over the centuries an element of compositeness emerges almost in every culture. When, due to a natural calamity or political exigencies, people move from one part of the world to another, they carry with them, among other things, their language, cultural inheritance and their ways of living.

In the light of the above facts, it is not at all surprising that comparative anthropologists and philologists are intrigued by the striking similarity between different language families and the rites, rituals and myths of different peoples. Speculative philosophers of history, heavily relying on the findings of epigraphy, ethnography, archaeology and theology, try to show in very general terms that the particulars and universals of culture are "essentially" or "secretly" interrelated. The spiritual aspects of culture like dance and music, beliefs pertaining to life, death and duties, on analysis, are found to be mediated by the material forms of life like weather forecasting, food production, urbanization and invention of script. The transition from the oral culture to the written one was made possible because of the mastery of symbols and rules of measurement. Speech precedes grammar, poetry, prosody. All these show how the "matters" and "forms" of life are so subtly interwoven.

II

The PHISPC publications on History of Science, Philosophy and Culture in Indian Civilization, in spite of their unitary look, do recognize the differences between the areas of material civilization and those of ideational culture. It is not a work of a single author. Nor is it being executed by a group of thinkers and writers who are methodologically uniform or ideologically identical in their commitments. In conceiving the Project we have interacted with, and been influenced by, the writings and views of many Indian and non-Indian thinkers.

The attempted unity of this Project lies in its aim and inspiration. We have in India many scholarly works written by Indians on different aspects of our civilization and culture. Right from the pre-Christian era to our own time, India has drawn the attention of various countries of Asia, Europe and Africa. Some of these writings are objective and informative and many others are based on insufficient information and hearsay, and therefore not quite reliable, but they have their own value. Quality and view-points keep on changing not only because of the adequacy and inadequacy of evidence but also, and perhaps more so, because of the bias and prejudice, religious and political conviction, of the writers.

Besides, it is to be remembered that history, like Nature, is not an open book to be read alike by all. The past is mainly enclosed and only partially disclosed. History is, therefore, partly objective or "real" and largely a matter of construction. This is one of the reasons why some historians themselves think that it is a form of literature or art. However, it does not mean that historical construction is "anarchic" and arbitrary. Certainly, imagination plays an important role in it.

But its character is basically dependent upon the questions which the historian raises and wants to understand or answer in terms of the ideas and actions of human beings in the past ages. In a way, history, somewhat like the natural sciences, is engaged in answering questions and in exploring relationships of cause and effect between events and developments across time. While in the natural sciences, the scientist poses questions about nature in the form of hypotheses, expecting to elicit authoritative answers to such questions, the historian studies the past, partly for the sake of understanding it for its own sake and partly also for the light which the past throws upon the present, and the possibilities which it opens up for moulding the future. But the difference between the two approaches must not be lost sight of. The scientist is primarily interested in discovering laws and framing theories, in terms of which different events and processes can be connected and anticipated. His interest in the conditions or circumstances attending the concerned events is secondary. Therefore, scientific laws turn out to be basically abstract and easily expressible in terms of mathematical language. In contrast, the historian's main interest centres round the specific events, human ideas and actions, not general laws. So, the historian, unlike the scientist, is obliged to pay primary attention to the circumstances of the events he wants to study. Consequently, history, like most other humanistic disciplines, is concrete and particularist. This is not to deny the obvious truth that historical events and processes consisting of human ideas and actions show some trend or other and weave some pattern or other. If these trends and patterns were not there at all in history, the study of history as a branch of knowledge would not have been profitable or instructive. But one must recognize that historical trends and pattern, unlike scientific laws and theories, are not general or purported to be universal in their scope.

III

The aim of this Project is to discover the main aspects of Indian culture and present them in an interrelated way. Since our culture has influenced, and has been influenced by, the neighbouring cultures of West Asia, Central Asia, East Asia and South- East Asia, attempts have been made here to trace and study these influences in their mutuality. It is well known that during the last three centuries, European presence in India, both political and cultural, has been very widespread. In many volumes of the Project, considerable attention has been paid to Europe and through Europe to other parts of the world. For the purpose of a comprehensive cultural study of India, the existing political boundaries of the South Asia of today are more of a hindrance than help. Cultures, like languages, often transcend the bounds of changing political territories.

If the inconstant political geography is not a reliable help to the understanding of the layered structure and spread of culture, a somewhat comparable problem is encountered in the area of historical periodization. Periodization or segmenting time is a very tricky affair. When exactly one period ends and another begins is not precisely ascertainable. The periods of history designated as ancient, medieval and modern are purely conventional and merely heuristic in character. The varying scopes of history, local, national and continental or universal, somewhat like the periods of history, are unavoidably fuzzy and shifting. Amidst all these difficulties, the volume-wise details have been planned and worked out by the editors in consultation with the Project Director and the General Editor. I believe that the editors of different volumes have also profited from the reactions and suggestions of the contributors of individual chapters in planning the volumes.

Another aspect of Indian history which the volume-editors and contributors of the Project have carefully dealt with is the distinction and relation between civilization and culture. The material conditions which substantially shaped Indian civilization have been discussed in detail. From agriculture and industry to metallurgy and technology, from physics and chemical practices to the life sciences and different systems of medicines - all the branches of knowledge and skill which directly affect human life - form the heart of this Project. Since the periods covered by the PHISPC are extensive - prehistory, proto-history, early history, medieval history and modern history of India - we do not claim to have gone into all the relevant material conditions of human life. We had to be selective. Therefore, one should not be surprised if one finds that only some material aspects of Indian civilization have received our pointed attention, while the rest have been dealt with in principle, or only alluded to.

One of the main aims of the Project has been to spell out the first principles of the philosophy of different schools, both pro-Vedic and anti-Vedic. The basic ideas of Buddhism, jainism and Islam have been given their due importance. The special position accorded to philosophy is to be understood partly in terms of its proclaimed unifying character and partly to be explained in terms of the fact that different philosophical systems represent alternative world-views, cultural perspectives, their conflict and mutual assimilation.

Most of the volume-editors and at their instance the concerned contributors have followed a middle path between the extremes of narrativism and theoreticism. The underlying idea has been this: If, in the process of working out a comprehensive Project like this, every contributor attempts to narrate all those interesting things that he has in the back of his mind, the enterprise is likely to prove unmanageable. If, on the other hand, particular details are consciously forced into a fixed mould or presupposed theoretical structure, the details lose their particularity and interesting character. Therefore, depending on the nature of the problem of discourse, most of the writers have tried to reconcile in their presentation, the specificity of narrativism and the generality of theoretical orientation. This is a conscious editorial decision.

Because, in the absence of a theory, however inarticulate it may be, the factual details tend to fall apart. Spiritual network or theoretical orientation makes historical details not only meaningful but also interesting and enjoyable.

Another editorial decision which deserves spelling out is the necessity or avoid- ability of duplication of the same theme in different volumes or even in the same volume. Certainly, this Project is not an assortment of several volumes. Nor is any volume intended to be a miscellany. This Project has been designed with a definite end in view and has a structure of its own. The character of the structure has admittedly been influenced by the variety of the themes accommodated within it. Again, it must be understood that the complexity of structure is rooted in the aimed integrality of the Project itself.

IV

Long and in-depth editorial discussion has led us to several unanimous conclusions. Firstly, our Project is going to be unique, unrivalled and discursive in its attempt to integrate different forms of science, technology, philosophy and culture. Its comprehensive scope, continuous character and accent on culture distinguish it from the works of such Indian authors as P.C. Ray, B.N. Seal, Binoy Kumar Sarkar and S.N. Sen and also from such Euro-American writers as Lynn Thorndike, George Sarton and Joseph Needham. Indeed, it would be no exaggeration to suggest that it is for the first time that an endeavour of so comprehensive a character, in its exploration of the social, philosophical and cultural characteristics of a distinctive world civilization - that of India - has been attempted in the domain of scholarship.

Secondly, we try to show the linkages between different branches of learning as different modes of experience in an organic manner and without resorting to a kind of reductionism, materialistic or spiritualistic. The internal dialectics of organicism without reductionism allows fuzziness, discontinuity and discreteness within limits.

Thirdly, positively speaking, different modes of human experience - scientific, artistic, etc., have their own individuality, not necessarily autonomy. Since all these modes are modification and articulation of human experience, these are bound to have between them some finely graded commonness. At the same time, it has been recognized that reflection on different areas of experience and investigation brings to light new insights and findings. Growth of knowledge requires humans, in general, and scholars, in particular, to identify the distinctness of different branches of learning.

Fourthly, to follow simultaneously the twin principles of: (a) individuality of human experience as a whole, and (b) individuality of diverse disciplines, is not at all an easy task. Overlap of themes and duplication of the terms of discourse become unavoidable at times. For example, in the context of Dharmasastra, the writer is bound to discuss the concept of value. The same concept also figures in economic discourse and also occurs in a discussion on fine arts. The conscious editorial decision has been that, while duplication should be kept to its minimum, for the sake of intended clarity of the themes under discussion, their reiteration must not be avoided at high intellectual cost.

Fifthly, the scholars working on the Project are drawn from widely different disciplines. They have brought to our notice an important fact that has clear relevance to our work. Many of our contemporary disciplines like economics and sociology did not exist, at least not in their present form, just two centuries ago or so. For example, before the middle of nineteenth century, sociology as a distinct branch of knowledge was unknown. The term is said to have been coined first by the French philosopher Auguste Comte in 1838. Obviously, this does not mean that the issues discussed in sociology were not there. Similarly, Adam Smith's (1723-90) famous work, The Wealth of Nations, is often referred to as the first authoritative statement of the principles of (what we now call) economics. Interestingly enough, the author was equally interested in ethics and jurisprudence. It is clear from history that the nature and scope of different disciplines undergo change, at times very radically, over time. For example, in India "Arthasastra' does not mean the science of economics as understood today. Besides the principles of economics, the Arthasdstra of ancient India discusses at length those of governance, diplomacy and military science.

Sixthly, this brings us to the next editorial policy followed in the Project. We have tried to remain very conscious of what may be called indeterminacy or inexactness of translation. When a word or expression of one language is translated into another, some loss of meaning or exactitude seems to be unavoidable. This is true not only in the bilingual relations like Sanskrit-English and Sanskrit-Arabic, but also in those of Hindi-Tamil and Hindi-Bengali. In recognition of the importance of language-bound and context-relative character of meaning, we have solicited from many learned scholars, contributions, written in vernacular languages. In order to minimize the miseffect of semantic inexactitude we have solicited translational help of that type of bilingual scholars who know both English and the concerned vernacular language, Hindi, Tamil, Telugu, Bengali or Marathi.

Seventhly and finally, perhaps the place of technology as a branch of knowledge in the composite universe of science and art merits some elucidation. Technology has been conceived in very many ways, e.g., as autonomous, as "standing reserve", as liberating or enlargemental, and alienative or estrangemental force. The studies undertaken by the Project show that, in spite of its much emphasized mechanical and alienative characteristics, technology embodies a very useful mode of knowledge that is peculiar to man. The Greek root words of technology are techne (art) and logos (science). This is the basic justification of recognizing technology as closely related to both epistemology, the discipline of valid knowledge, and axiology, the discipline of freedom and values. It is in this context that we are reminded of the definition of man as homo technikos. In Sanskrit, the word closest to techne is kala which means any practical art, any mechanical or fine art. In the Indian tradition, in Saivatantra, for example, among the arts (kala) are counted dance, drama, music, architecture, metallurgy, knowledge of dictionary, encyclopaedia and prosody. The closeness of the relation between arts and sciences, technology and other forms of knowledge are evident from these examples and was known to the ancient people. The human quest for knowledge involves the use of both head and hand. Without mind, the body is a corpse and the disembodied mind is a bare abstraction. Even for our appreciation of what is beautiful and the creation of what is valuable, we are required to exercise both our intellectual competence and physical capacity. In a manner of speaking, one might rightly affirm that our psychosomatic structure is a functional connector between what we are and what we could be, between the physical and the beyond. To suppose that there is a clear-cut distinction between the physical world and the psychosomatic one amounts to denial of the possible emergence of higher logico-mathematical, musical and other capacities. The very availability of aesthetic experience and creation proves that the supposed distinction is somehow overcome by what may be called the bodily self or embodied mind.

v

The ways of classification of arts and sciences are neither universal nor permanent. In the Indian tradition, in the Rg-veda, for example, vidyas (or sciences) are said to be four in number: (i) Trayi, the triple Veda; (ii) anviksiki, logic and metaphysics; (iii) Danda-niti, science of governance; (iv) Vartta, practical arts such as agriculture, commerce, medicine, ete. Manu speaks of a fifth vidya, viz., atma-vidya, knowledge of self or of spiritual truth. According to many others, vidya has fourteen divisions, viz., the four Vedas, the six Vedangas, the Puranas, the Mimamsa; Nyaya, and Dharma or law. At times, the four Upa-vedas are also recognized by some as vidya. Kalas are said to be 33 or even 64.

In the classical tradition of India, the word sastra has at times been used as synonym of vidya. Vidya denotes instrument of teaching, manual or compendium of rules, religious or scientific treatise. The word sastra is usually found after the word referring to the subject of the book, e.g., Dharmasastra, Arthasastra, Alankarasastra and Moksasastra. Two other words which have been frequently used to denote different branches of knowledge are jnana and vijnana. While jnana means knowing, knowledge, especially the higher form of it; vijnana stands for the act of distinguishing or discerning, understanding, comprehending and recognizing. It means worldly or profane knowledge as distinguished from jnana, knowledge of the divine.

It must be said here that the division of knowledge is partly conventional and partly administrative or practical. It keeps on changing from culture to culture, from age to age. It is difficult to claim that the distinction between jnana and vijnana or that between science and art is universal. It is true that even before the advent of the modern age, both in the East and the West, two basic aspects of science started gaining recognition. One is the specialized character of what we call scientific knowledge. The other is the concept of trained skill which was brought close to scientific knowledge. In the medieval Europe, the expression "the seven liberal sciences" has so often been used simultaneously with "the seven liberal arts", meaning thereby, the group of studies by the Trivium (Grammar, Logic and Rhetoric) and Quadrivium (Arithmetic, Music, Geometry and Astronomy).

It may be observed here, as has already been alluded to earlier, that the division between different branches of knowledge, between theory and practice, was not pushed to an extreme extent in the early ages. Praxis, for example, was recognized as the prime techne. The Greek word technologia stood for systematic treatment, for example, of Grammar. Praxis is not the mere application of theoria, unified vision or integral outlook, but it also stands for the active impetus and base of knowledge. In India, one often uses the terms Prayukti-vidya and Prayodyogika-vidya to emphasize the practical or applicative character of knowledge. Prayoga or application is both the test and base of knowledge. Doing is the best way of knowing and learning.

That one and the same word may mean different "things" or concepts in different cultures and thus create confusion has already been stated before. Two such words which in the context of this Project under discussion deserve special mention are dharma and itihasa. Ordinarily, dharma in Sanskrit-rooted languages is taken to be the conceptual equivalent of the English word religion. But, while the meaning of religion is primarily theological, that of dharma seems to be manifold. Literally, dharma stands for that which is established or that which holds people steadfastly together. Its other meanings are law, rule, usage, practice, custom, ordinance and statute. Spiritual or moral merit, virtue, righteousness and good works are also denoted by it. Further, dharma stands for natural qualities like burning (of fire), liquidity (of water) and fragility (of glass). Thus one finds that meanings of dharma are of many types - legal, social, moral, religious or spiritual, and even ontological or physical. All these meanings of dharma have received due attention of the writers in the relevant contexts of different volumes.

This Project, being primarily historical as it is, has naturally paid serious attention to the different concepts of history-epic-mythic, artistic-narrative, scientific-causal, theoretical and ideological. Perhaps the point that must be mentioned first about history is that it is not a correct translation of the Sanskrit word itihasa. Etymologically, it means what really happened (iti-ha-asa). But, as we know, in the Indian tradition purana (legend, myth, tale, etc.), gatha (ballad), itivrtta (description of past occurrence, event, etc.), akhyayika (short narrative) and vamsa-carita (genealogy) have been consciously accorded a very important place. Things started changing with the passage of time and particularly after the effective presence of Islamic culture in India. Islamic historians, because of their own cultural moorings and the influence of the Semitic and Graeco-Roman cultures on them, were more particular about their facts, figures and dates than their Indian predecessors. Their aim to bring history close to statecraft, social conditions and the lives and teachings of the religious leaders imparted a mundane character to this branch of learning. The Europeans whose political appearance on the Indian scene became quite perceptible only towards the end of the eighteenth century brought in with them their own view of historiography in their cultural baggage. The impact of the Newtonian Revolution in the field of history was very faithfully worked out, among others, by David Hume (1711-76) in History of Great Britain from the Invasion of Julius Caesar to the Revolution of 1688 (6 Vol. 1754-62) and Edward Gibbon (1737-94) in The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire (6 Vol., 1776-88). Their emphasis on the principles of causality, datability and continuity/linearity of historical events introduced the spirit of scientific revolution in European historiography. The introduction of English education in India and the exposure of the elites of the country to it largely account for the decline of the traditional concept of itihasa and the rise of the post-Newtonian scientific historiography. Gradually, Indian writers of our own history and cultural heritage started using more and more European concepts and categories. This is not to suggest that the impact of the European historiography on Indian historians was entirely negative. On the contrary, it imparted an analytical and critical temper which motivated many Indian historians of the nineteenth century to try to discover and represent our heritage in a new way.

VI The principles which have been followed for organizing the subjects of different volumes under this Project may be stated in this way. We have kept in view the main structures which are discernible in the decomposible composition of the world. The first structure may be described as physical and chemical. The second structure consists, broadly speaking, of biology, psychology and epistemology. The highest and the most abstract structure nests many substructures within it, for example, logic, mathematics and musical notes. It is well known that the substructures within each structure are interactive, i.e., not isolable. The more important point to be noted in this connection is that the basic three structures of the world, viz., (a) physicochemical, (b) bio-psychological, and (c) logico-mathematical are all simultaneously open to upward and downward causation. In other words, while the physicochemical structure can causally influence the bio-psychological one and the latter can causally influence the most abstract logico-mathematical, the reverse process of causation is also operative in the world. In spite of its relative abstractness and durability, the Iogico-mathematical world has its downward causal impact on our bio-psychological and epistemological processes and products. And the latter can also bring about change in the structures of the physical world and its chemical composition. Applied physics and bio-technology make the last point abundantly clear.

Many philosophers, life-scientists, and social scientists highlight the point that nature loves hierarchies. Herbert Simon, the economist and the management scientist, speaks of four steps of partial ordering of our world, namely; (i) chemical substances, (ii) living organisms, tissues and organs, (iii) genes, chromosomes and DNA, and (iv) human beings, the social organizations, programmes and information process. All these views are in accord with the anti-reductionist character of our Project. Many biologists defend this approach by pointing out that certain characteristics of biological phenomena and processes like unpredictability, randomness, uniqueness, magnitude of stochastic perturbations, complexity and emergence cannot be reduced without recourse to physical laws.

The main subjects dealt with in different volumes of the Project are connected not only conceptually and synchronically but also historically or diachronically. For pressing practical reasons, however, we did not aim at presenting the prehistorical, proto-historical and historical past of India in a continuous or chronological manner. Besides it has been shown in the presentation of the PHISPC that the process of history is non-linear. And this process is to be understood in terms of human praxis and an absence of general laws in history. Another point which deserves special mention is that the editorial advisors have taken a conscious decision not to make this historical Project primarily political. We felt that this area of history has always been receiving extensive attention. Therefore, the customary discussion of dynastic rule and succession will not be found in a prominent way in this series. Instead, as said before, most of the available space has been given to social, scientific, philosophical and other cultural aspects of Indian civilization.

Having stated this, it must be admitted that our departure from conventional style of writing Indian history is not total. We have followed an inarticulate framework of time in organizing and presenting the results of our studies. The first volume, together with its parts, deals with the prehistorical period to A.D. 300. The next two volumes, together with their parts, deal with, among other things, the development of social and political institutions and philosophical and scientific ideas from A.D. 300 to the beginning of the eleventh century A.D. The next period with which this Project is concerned spans from the twelfth century to the early part of the eighteenth century. The last three centuries constitute the fourth period covered by this Project. But, as said before, the definitions of all these periods by their very nature are inexact and merely indicative.

Two other points must be mentioned before I conclude this General Introduction to the series. The history of some of the subjects like religion, language and literature, philosophy, science and technology cannot, for obvious reason, be squeezed within the cramped space of the periodic moulds. Attempts to do so result in thematic distortion. Therefore, the reader will often see the overflow of some ideas from one period to another. I have already drawn attention to this tricky and fuzzy, and also the misleading aspects of the periodization of history, if pressed beyond a point.

Secondly, strictly speaking, history knows no end. Every age rewrites its history. Every generation, best with new issues, problems and questions, looks back to its history and reinterprets and renews its past. This shows why history is not only contemporaneous but also futural. Human life actually knows no separative wall between its past, present and future. Its cognitive enterprises, moral endeavours and practical activities are informed of the past, oriented by the present and addressed to the future. This process persists, consciously or unconsciously, wittingly or unwittingly. In the narrative of this Project, we have tried to represent this complex and fascinating story of Indian civilization.

| Preface | xiii | |

| Foreword | xvii | |

| Contributors | xix | |

| General Introduction | xxvii | |

| I. CONSCIOUSNESS IN THE INDIAN TRADITION | ||

| Chapter 1 | Yoga: Science and Technology of Consciousness | 3 |

| Chapter 2 | Sri Aurobindo's Evolutionary Ontology of Consciousness | 11 |

| Chapter 3 | Centrality of Consciousness in Indian Psychology | 53 |

| Chapter 4 | The Theme of Consciousness in Indian Culture | 76 |

| II. SCHOOLS OF YOGA-SADHANA | ||

| Chapter 5 | The Vedic Seer's Quest for the Supramental Consciousness | 91 |

| Chapter 6 | The Tradition of the Buddhist Yoga | 104 |

| Chapter 7 | Stages of Spiritual Development in Jainism | 117 |

| Chapter 8 | Nature of Consciousness and Yoga in Kasmira Saiva Tantra | 123 |

| Chapter 9 | Chakra Meditation in Achieving Altered States of Consciousness | 130 |

| Chapter 10 | Sikhism and the Yoga Tradition | 137 |

| Chapter 11 | Spiritual Experiences of Ramakrishna-Vivekananda | 145 |

| Chapter 12 | The Science of Kriya Yoga | 177 |

| Chapter 13 | Essentials of Transformative Psychology | 191 |

| III. PSYCHOLOGY AND THE INDIAN TRADITION: | ||

| IN SEARCH OF A MEETING GROUND | ||

| Chapter 14 | Challenges and Opportunities for Indian Psychology | 205 |

| in a Rapidly Globalizing Post-modern World | ||

| Chapter 15 | Psychology in India: Past Trends and Future Possibilities | 224 |

| Chapter 16 | Relativism and Its Relevance for Psychology | 238 |

| Chapter 17 | Personal Growth and Psychology in India | 248 |

| Chapter 18 | Rising Up to the Supramental Consciousness: The Need for a New Psychology | 257 |

| Chapter 19 | Psychology in India: A Future Perspective | 264 |

| IV. INDIAN PSYCHOLOGY: SOME THEORETICAL ISSUES | ||

| Chapter 20 | Yoga and Knowledge | 271 |

| Chapter 21 | Old Ideas of Mind | 278 |

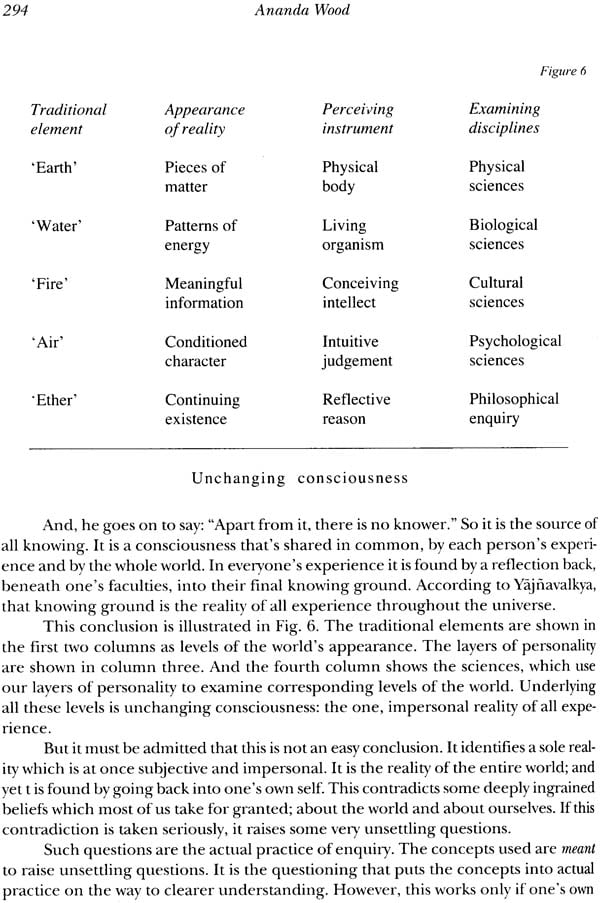

| Chapter 22 | The Concept of Mind in Orthodox Indian Thought: Its Implications for Modern Psychology | 296 |

| Chapter 23 | An Information Theoretic Approach to the Issues of The Collective Unconscious and the Superconscious | 307 |

| Chapter 24 | Emotion in Modern Psychology and Indian Thought | 314 |

| Chapter 25 | Indian Concepts of Personality | 332 |

| Chapter 26 | The Meeting of East and West: The Fusion of Vedanta | 342 |

| and Western Psychology in Integral Psychology | ||

| Chapter 27 | Revitalizing Developmental Psychology: | 353 |

| Sri Aurobindo's Theory of Human Development | ||

| V. INDIAN PSYCHOLOGY APPLIED | ||

| Chapter 28 | The Yogic View of Life with Special Reference to Medicine | 371 |

| Chapter 29 | A Holistic Model of Sustainable Development: An Indian Approach to Environmental Psychology | 379 |

| Chapter 30 | The Flowering of Aravind Eye Care System | 391 |

| Chapter 31 | Spiritual Health of Organizations: A New Vision | 404 |

| of Organizational Change in Rural Bank Development | ||

| Chapter 32 | An Indian Approach of Psychotherapy: | 419 |

| Sattvavajaya- Concept and Application | ||

| Chapter 33 | Sahya: The Concept in Indian Philosophical Psychology and Its Contemporary Relevance | 426 |

| Chapter 34 | Spiritual Depths of Admiration in Family Therapy: | 436 |

| Grhastha -Family Life as a Spiritual Path | ||

| Chapter 35 | Intervention for Cancer through Intergral Psychotherapy | 444 |

| Chapter 36 | Yoga as an Intervention Strategy for Augmenting Spiritual | 461 |

| Intelligence | ||

| Index | 471 |