A Portrayal of People: Essays on Visual Authropology in India (An Old and Rare Book)

Book Specification

| Item Code: | NAJ261 |

| Publisher: | Anthropological Survey of India, Kolkata |

| Language: | English |

| Edition: | 1987 |

| Pages: | 200 (14 B/W Illustrations) |

| Cover: | Paperback |

| Other Details | 8.5 inch X 6 inch |

| Weight | 360 gm |

Book Description

Foreword

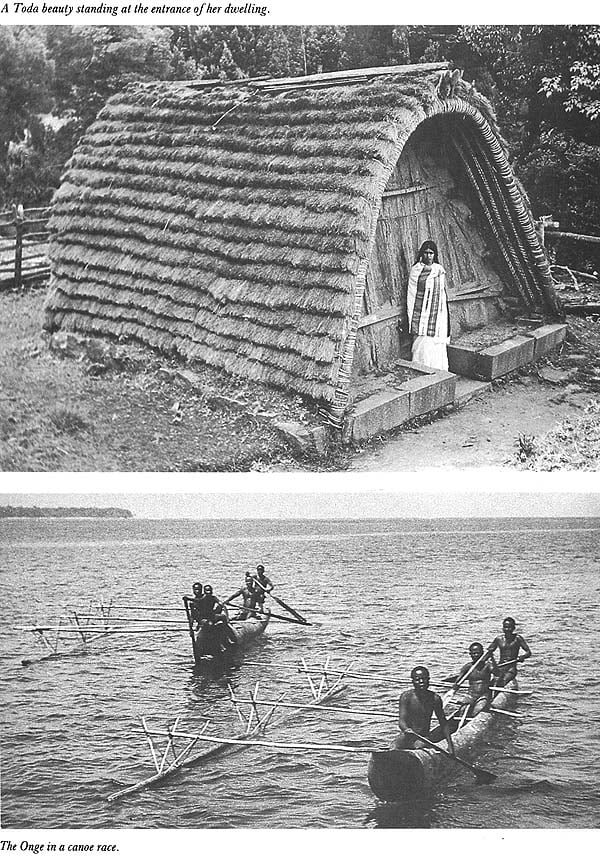

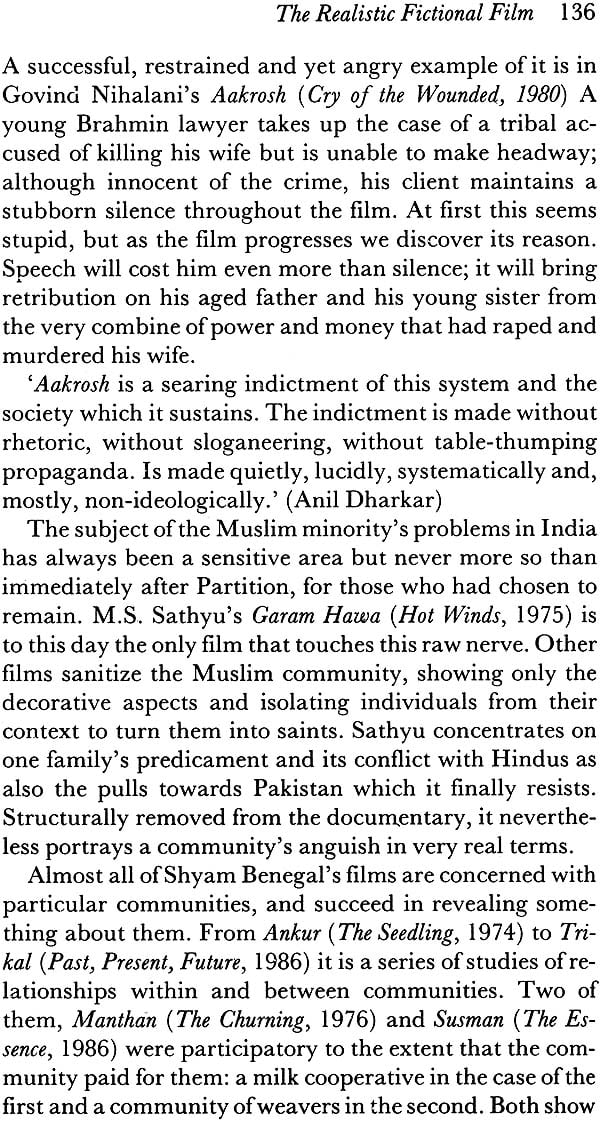

It has often been said that India lives in many centuries at the same time. The complex network of diversity that stretches across time and space has made India a paradise for anthropologists. Not all of them have come from abroad, or represented a colonial relationship; India’s own achievement in this discipline has been considerable, thanks to the outstanding contribution of individual anthropologists and to the Anthropological Survey of India (ASI). Even in the visual field the range of work seems formidable if one takes into account the non-formal, but nonetheless important, study of communities expressed in the documentary film and the fictional cinema meant for the general public, in addition to the visual records for academia made by the Anthropological Survey of India ·n its 50-odd films and thousands of still photographs. Many streams have thus contributed to the development of visual anthropology in India which is a relatively nascent sub-discipline of anthropology.

However, the entire range of activity in this area has suffered from many shortcomings. The formal part of visual anthropology never received sufficient emphasis to adapt itself to changing technologies constantly simplifying and improving the work of the filmmaker. The non formal, addressed to huge audiences, has naturally used technology most suited to its primary purposes of large-scale information and propaganda or entertainment. Even the ASI, after a glorious start, could not keep pace with the advances in technology. It is here that visual anthropology in the West, being consciously tuned to the importance of the visual experience within the academic discipline, has scored by developing a multiplicity of experiments with the form of visual anthropology by adopting light-weight cameras and sound-recording equipment of considerable sophistication and low cost. From l6 mm to video and now to equipment that is extremely small in size and low in weight, a progressive simplification of the paraphernalia is beginning to make film-making as easy and as solitary an act-s-jean Cocteau’s dream-as writing a book.

All you have to know is the language of cinema.

The need for taking the Indian experience forward was articulated by Jaysinhji Jhala, an Indian visual anthropologist working at Harvard, who has made a number of ethnographic films in Gujarat and in North- east India. INTACH agreed readily to his proposal for an international seminar on visual anthropology. With a similar readiness on the part of the ASI the seminar became possible. The Anthropological Survey of India, which has emerged as the largest repository of visual materials, came forward to share its experience not only in formulating the plan for the Seminar but also its resources in organising it. INTACH and ASI are co-sponsors of the seminar and its publications. The ASI seeks to expose its technical experts to the new waves generated in recent years in the field of visual anthropology and looks forward to the experience of the seminar in formulating its own perspective in visual anthropology as part of the larger policy on documentation and dissemination of cultures.

Others who responsed were Dr. Surajit Sinha, Prof. T.N. Madan of the Institute of Economic Growth, Prof. T.K. Oommen of Jawaharlal Nehru University, Prof. K.N. Sahay of Ranchi University, whose advice and help led to the orientation and organisation of the Seminar. It has also been encouraging to note the interest in the Seminar among the media concerned with film-making, such as Doordarshan, Films Division, Government of India (one of the world’s largest producers of documentary films), Directors of Film Festivals and independent film directors.

It was decided to bring together many perspectives-at present somewhat dispersed-in visual anthropology generated by the Anthropological Survey of India, professional anthropologists, filmmakers, etc. In preparing this report on the state of visual anthropology for the Seminar we have amply succeeded. However, one significant dimension that is missing in our effort is the role of the museums of tribal research institutions and some State museums which have done commendable work in building up visual documentation on the people of India. The fictional film, not habitually counted among the forms of visual anthropology, has been given a place in the deliberations of the Seminar. Ashish Rajadhyaksha’s paper at the seminar will deal with it in some detail, and the presence of some noted feature filmmakers should help consolidate this extension of the area of interest for visual anthropology.

The purpose of the present publication is to provide a glimpse, far from comprehensive, of the state of the art in India on the eve of a gathering of some its outstanding exponents from many parts of the world.

Introduction

I welcome the initiative taken by the Indian National Trust for Art and Cultural Heritage and the Anthropological Survey of India in organising an International Seminar on Visual Anthropology at Jodhpur.

Although anthropologists have long been utilising visual representation-sketches, drawings, still photographs, and later, movie cameras for field research, ‘visual anthropoiogy’ emerged as a specialised sub-discipline of anthropology only during the last two decades. Its domain of discourse, however, has still to be clearly defined and the sub-discipline is in a state of, becoming’.

Intensive observation of the activities of a people in the totality of a social and environmental context has been the main method of anthropological field research. Although anthropologists depend primarily upon written representation for the communication of what they observe or hear from the people, it is obvious that many aspects of ‘facework’, socially and culturally defined body movements, and organisation of ‘social space’ are lost in the process. The still camera, the movie camera and the instruments for sound recording can greatly enlarge the scope for probing deeply into the activities and responses of a people, compared to the records based on personal visual memory. Photographic and audio-visual cinematographic records, however, are not merely mechanical extensions of things which can be seen and heard without the aid of instruments. Appropriate use of still and movie cameras demands a meaningful combination of the precision of a natural-historical approach with humane audio-visual sensitivity about the responses of the people. Experiments have been going on in working out the optimal team work for achieving the desired result: a combined team of an anthropologist and filmmaker; an anthropologist turned into a filmmaker (Rouch), a filmmaker turned into an anthropologist (Flaherty). It is obvious that in these collaborative ventures, either in the form of the meeting of two disciplines in a single person or as a combined team of an anthropologist and a filmmaker, the anthropologist must have a clear knowledge of the possibilities and constraints of the language of film, and the anthropological filmmaker must be familiar with the cumulatively developed theoretical and methodological interests in anthropology, particularly with recent trends in ethnographic reporting.

Anthropologists have often been involved in a debate on whether the discipline aims mainly at scientific generalisations about human societies and cultures or is basically an exercise in the ideographic descriptive integration of observed data. I think while the debate continues, in practice, anthropologists have learnt to live with a combined endeavour: controlled comparison of observed data and presentation of ‘thick descriptions’ or portrayals of socially defined activities, probing deeply into the underlying symbolic structure-the world of ‘meaning’ of a group of people. Both anthropologists and filmmakers are in a way fellow-travellers-they are interested in the perceptive and authentic reconstruction and representation of the reality of the human condition. While fictional filmmakers have to transform written scripts into visual representation, anthropologists transform visual impressions into written presentations. Anthropologists, however, do not have the freedom to creatively arrange totally imaginary persons and sequences of events in their ethnographic portrayals. They cannot create Apu, Durga and Indir Thakrun and the events presented in the book and film, Pather Panchali. The perceptive anthropologist will, however, find that the penetrating imaginary construction of social environment and socially situated persons, in fictions and fictional films may sometimes provide deep insights into the human condition, often missed by the anthropologist on account of his excessively cautious concern for mechanical observation of all things happening.

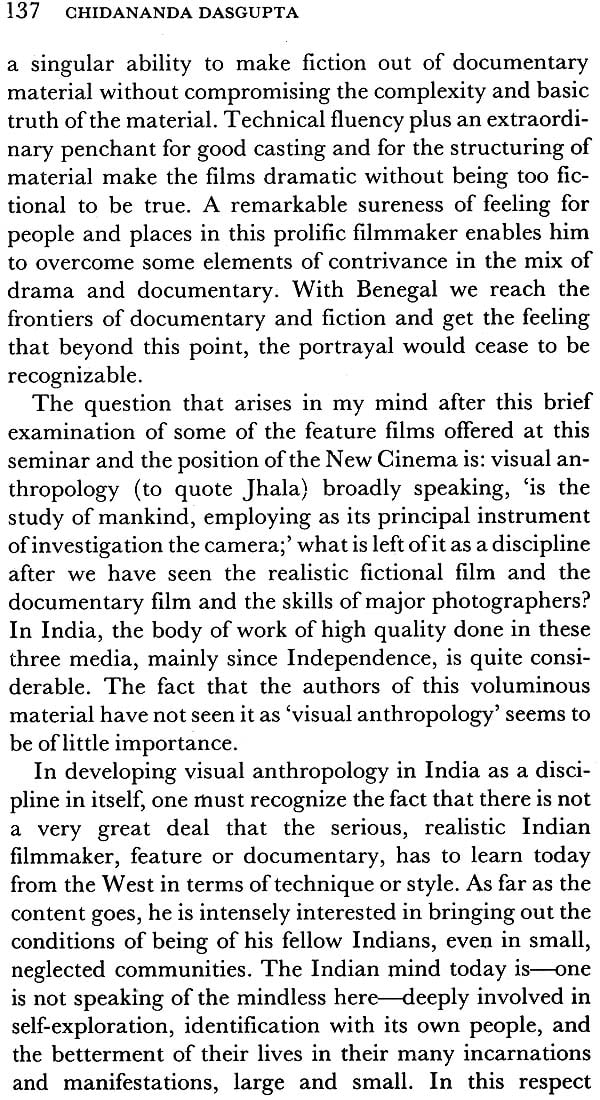

Chidananda Das Gupta in his article ‘The Realistic Fictional Film: How Far From Visual Anthropology?’ points out how, in contrast to documentary films, fictional films are concerned with the ‘reality under the surface’. Das- Gupta raises the question whether, after covering the high quality reached by some professional photographers, documentary filmmakers and realistic fictional filmmakers, much is left for visual anthropology as a discipline!

It is interesting to note that in response to Someswar Bhowmik’s query about how he rated Mrigaya from an anthropological point of view, Mrinal Sen responded: ‘1 frankly tell you 1 haven’t been able to capture the complexity of tribal life.’ Sen feels that ‘any creative worker, whether he is in cinema or in some other medium, has to be some kind of an anthropologist’. Perhaps Sen wanted to emphasise the importance of looking into the behaviour of little known people from their endogenous social norms and world-views.

Several writers in this volume (Jhala and Roy, Das- Gupta and Sahay) have emphasised the need for dialogue, effective two-way communication, between the filmmaker-observer and the observed. It is expected that some of the anthropological films will emerge as genuine forums for wider communication for the silent voices of little known tribal and peasant groups. It is also expected that the ‘subjects’ of anthropological films may become interested not only in seeing themselves in films or making comments on the authenticity of the portrayals, but in being spokesmen of their own societies, as filmmakers. Roy and Jhala in their paper ‘Perceptions of the Self and Other in Visual Anthropology’ present the case of their three experiences in visual anthropology: (i) the Wangchu (Forgotten Headhunters). The Bharvad (Bharvad Predicament) and the Rajput (A Zenana). In the case of the film on the Wangchu of Arunachal Pradesh the recognized official objective was to ‘salvage visual anthropology’. Under the limiting circumstances of official sponsorship there was no sense of participation in an ethnic event-a distance was maintained whereby no meaningful interaction between the people and the filmmakers could take place.

In the case of filming the Bharvad pastoralists of Jesod village of Gujarat, the terrain and the people were already known to the filmmakers. They were able to become ‘the chronicler, confidante and adviser to the filmed other’ Here ideas, inspirations and fears became the central focus of presentation. Jhala and Roy state that one may meet a Bharvad ‘man’ in the bus or town, ‘person’ in his village home and self (jiu) only on the grasslands. For a full understanding of the Bharvad self ‘it is imperative that the filmmakers record Bharvad interaction with their cattle.

The third film venture, A Zenana, focussed on the area of residence of a Hindu Rajput family, to which the filmmakers were son and daughter-in-law. This film was based principally on recording prolonged conversations and carefully focussing on the arrangement of social space.

Contents

| Foreword | v |

| Introduction | ix |

| An Examination of the Need and Potential for Visual Anthropology in India | 1 |

| Anthropological Survey of India and Visual Anthropology | 20 |

| History of Visual Anthropology in India | 49 |

| Perceptions of the Self and Other in Visual Anthropology | 75 |

| My Experiences as a Cameraman in the Anthropological Survey | 99 |

| The Vital Interface | 114 |

| The Realistic Fictional Film: How far from Visual Anthropology? | 127 |

| Phaniyamma and the Triumph of Asceticism | 139 |

| Images of Islam and Muslims on Doordarshan | 147 |

| Man in My Films | 161 |

| The Individual and Society | 169 |

| Notes on Contributors | 174 |