The Rigveda and the Avesta the Final Evidence

Book Specification

| Item Code: | IDK935 |

| Author: | Shrikant G. Talageri |

| Publisher: | ADITYA PRAKASHAN |

| Edition: | 2018 |

| ISBN: | 9788177420852 |

| Pages: | 417 (7 B/W Illustrations) |

| Cover: | Hardcover |

| Other Details | 8.8” X 5.8” |

Book Description

From the Jacket

The location of the Original Homeland of the Indo-European family of languages is the single most significant unresolved problem in the study of World History today. This is because it is the most important family of languages in terms of the number of primary as well as secondary speakers, as also in terms of geographical spread, ethnic diversity, and political and economic clout. This family of languages has twelve branches stretching between Celtic and Germanic in the west to Tocharian (extinct) and Indo-Aryan in the east. The question of the homeland of this diverse family has been hotly debated among linguists, historians, archaeologists and, especially in India, also among political writers of every brand.

In his two earlier books, The Aryan Invasion Theory: A Reappraisal (1993) and The Rigveda: A Historical Analysis (2000), the author of this book put forward the hypothesis, backed by detailed arguments and evidence, that this Original Homeland lay in the northern parts of India, and that the other branches of Indo-European languages spread out from India to their respective historical habitats. In this book, he presents the final case with conclusive new evidence based on a cogent interpretation of old but hitherto universally misinterpreted data.

By analyzing the ancient texts in full detail, this book establishes the relative chronology of the Rigveda vis-à-vis the Avesta and the Mitanni inscriptions; the geography of the Rigveda; the internal chronology of the (different parts of) the Rigveda; and, finally, the first steps in the establishment of the absolute chronology of the Rigveda, i.e. the actual point of time BCE when the hymns of the text were composed. Moreover, it presents linguistic evidence for the Indian Homeland hypothesis as the only one that explains all the linguistic problems arising in the course of the quest for the Original Homeland.

While the beginnings of the history of the Egyptian and the Mesopotamian Civilizations are known to lie at least as far back as the fourth millennium BCE on the basis of detailed decipherable and deciphered records, the beginnings of Indian Civilization as we know it could not really be traced far earlier than the Ashokan inscriptions of the third century BCE. The earlier records, the seals of the Harappan Civilization, are not yet convincingly deciphered; neither their language nor even whether they represent a language at all. However, ironically, decipherable records have been found in ‘West Asia, dating to the mind-second millennium BCE, which record the presence of Indo-Aryan-speakers, especially in the Mitanni kingdom. The analysis of the textual data in this book shows that the culture common to the Rigveda, the Avesta and the Mitanni records developed in northern India in the Late Rigvedic Period, and that the earlier periods, Middle Rigvedic and Early Rigvedic, saw not only the Indo-Aryans but also the proto-Iranians as inhabitants of areas deeper within northern India, whence they only expanded westwards towards the end of the Early Rigvedic Period.

Among its far-reaching implications, this solution of the academic question of the location of the Indo-European Homeland at once also resolves the puzzle of the Harappan Civilization’s linguistic identity and takes the beginnings of the India’s history (as distinct from its mute prehistory, which in present discourse includes the Harappan age) back by several thousands of years this lends legitimacy to an interpretation of Indian history with indigenous origins going back deep into the fourth millennium BCE, and brings Indian historical traditions (excluding the interpolated mythical elements and exaggerations) as well as the Harappan civilization within the ambits of Indian Civilization as we know it.

Preface

This book is entitled “The Rigveda and the Avesta: The Final Evidence” because it is intended to conclusively complete both the historical analysis of the Rigveda commenced in my second book, “The Rigveda: A Historical Analysis” (2000), as well as my examination of the Aryan invasion theory and the problem of the original homeland of the Indo-European family of languages commenced in my first book, “The Aryan Invasion Theory: A Reappraisal” (1993) [also published, earlier, by Voice of India, with three additional chapters of a political nature, as “The Aryan Invasion Theory and Indian Nationalism” (1993).]

When I started out on my first book, I was impelled by the conviction that the Aryan invasion theory taught in our school text books as fact had no logical basis, and was so totally opposed to everything that our traditional ideas of our history and heritage told us, that the matter required deep and detailed investigation, particularly in view of the blatant political misuse of the theory by various divisive political forces. However, neither then, nor at any other point of time along the course of the journey have I ever allowed my personal views to obscure or distort my perception and conclusions about the correct interpretation of the facts. So, even when my writing may occasionally have been handicapped by a lack of knowledge about some particular other books written on the subject, which therefore may have resulted in some deficiencies, those deficiencies have always been of a minor and incidental nature, and have never led me into the wrong direction. I can confidently (opponents may say, arrogantly) say that this book will set the seal on the controversy, and prove beyond and reasonable doubt that India was the original homeland of the Indo-European family of languages.

One person that I have to genuinely thank for this is Michael Witzel, the Wales Professor of Sanskrit at Harvard University. Throughout this present volume, I will be criticizing him sharply for the elements of fraudulent scholarship, and dirty politics, that he has introduced throughout the bitter debate on the subject, and for all the lies and manipulations that he has been guilty of in the process. But, at this point, I must admit that if he had not done all these things, I would never have been impelled to go as deeply into the matter as I have done after my second book, and this third book would not have been what it is – perhaps I would never have seen the need for a third book. His name will, therefore, necessarily be cropping up throughout this book.

My first book, in 1993, received some very favorable reviews, and even enthusiastic support, in various Indian circles. But even enthusiastic support, in various Indian circles. But western scholars, and Indian AIT scholars and writers, by and large, chose to refrain from reacting to it.

My second book, however, produced sharper reactions from some western scholars and writers. Even now, of course, the majority of AIT schools, Indian and western, involved in the AIT (Aryan Invasion Theory) vs. OIT (Out of India Theory) debate, or simply involved in the academic study of the Indo-European problem, still chose to treat silence as the safest form of defence, and continued to behave as if they had never even heard of my books – after all, it is easier to attack and ridicule the nonsensical notions and wishful writings of more casual or biased OIT writers than to deal with a logical and unassailable new hypothesis backed by a solid phalanx of facts and data. But, a smaller but significant number condescended to mention my name, only to dismiss me, either as a non-academic upstart who had the gall to think he could challenge eminent academic scholars, or simply as a politically motivated polemicist whose writings had no scholarly value.

While polemical discussions on the subject have raged on, mainly on the internet, between critics and defenders of my writings, they have been notable only for the incredibly consummate skill with which my critics managed to keep the discussions moving round and round in circles, centered on trivia and badinage, involving personal details concerning myself (from my alleged political opinions to my alleged lack of academic status, skills and qualifications), while completely skirting the objective issues of fact and data concerning the subject on hand.

The pathetic level of these discussions, and the degree of arrogance, virulence and venom spewed by the AIT protagonists, backed as they are by an immensely powerful array of vested interests, is frightening as a sample of the kind of academic environment prevailing today. But there is really no point in trading abuses or witty repartees with every (to used a typical Indian-English phrase) “time-pass” writer, whatever his academic status, who chooses to shoot off his mouth on the subject. I will only be dealing with Witzel’s shenanigans throughout this book, wherever called upon to do so.

But the fact is that the debate is no more only a debate between the AIT and OIT sides; it is more of a debate between subjective polemics, entrenched prejudices and dogmas, and academic vested interests, on the one hand, and objective analysis, rational logic and honest, open-minded scholarship, on the other. In this debate, the egos and prejudices of many OIT writers are as much a source of strength for the AIT side as they are a liability for the OIT side, not only in providing plenty of grist for the disinformation mills of the AIT writers, but also in contributing to keep the OIT side divided and effectively prevented from arriving at a rational agreement in their viewpoint.

In this context, I will mention only one OIT writer of this kind, because he has chosen to make his personal resentment public: the Greek writer Nicholas Kazanas. In his article “The Rigveda Date and Indigenism”. June 2006, on p. 10, he writes: “Indeed, in recent years also many publications advocated indigenism: Sethna 1992; Elst 1993; Frawley 1994 and with Rajaram 1997; Feuerstein et al 1995; and others”. In the footnote to this, he writes: “S. Talageri should perhaps be included but despite having some good ideas, this author knows no Sanskrit and has no training in Archaeology or other related disciplines and so goes astray constantly”

If Kazanas had merely refrained from mentioning my name in his list of writers who “advocated indigenism”, I would naturally have ignored the matter; but Kazanas chooses to make certain comments, and I will, only for this once, condescend to respond to them:

To begin with, whether or not Kazanas agrees with all the views expressed in my writings, and irrespective of his personal opinions of me, how can Kazanas claim that I do not fit into the single criterion mentioned by himself: of being the author of a publication which “advocated indigenism”, i.e. of being an “OIT” writer? What am I then to be classified as: an AIT writer? I would not, even in childish retaliation, seriously argue that Kazanas himself is not an OIT writer, any more than I could argue that he is not Greek, or he could argue that I am not an Indian. In fact, how many of those, named by himself in his list, would seriously agree with him, not only on my exclusion from a list of writers who “advocated indigenism”, but even on the deeper question of whether I “go astray constantly” and whether my work is therefore unfit for consideration? And even, let me add (even at the risk of sounding arrogant), on the basic question of whether their own names can be there in this particular context while mine is expressly excluded?

Secondly, do all the scholars named in his above list know Sanskrit (and Vedic Sanskrit at that), and do they all have “training in Archaeology or other related disciplines”?

The truth is that Kazanas initiated a discussion with me by e-mail, from 26/2/2005 to 28/4/2005, in which he tried to point-out mistakes in my book (TALAGERI 2000). I am always extremely grateful to people who point out mistakes (whether printing mistakes, or mistakes of fact, data or reasoning) in my writings, since it helps me to correct those mistakes; and, as I told him in that e-mail correspondence, I prefer to have alleged instances of serious mistakes and errors in my writings to be pointed out to me now, when I am alive to be able to either justify myself or to correct those mistakes, than to have them bandied about much later when I am dead and gone and no more able to reply. But, the discussion took an unfortunate turn, due to unreasonable remarks and arguments from his side, and I noticed that it was starting to move round and round in circles (like the internet discussions mentioned above); so we mutually, and (at least on my side) as amicably as possible, decided to close the discussion without bearing any resentment.

Apparently, Kazanas could not leave it at that. He had ended his side of the discussion with a Witzellian thrust, telling me that I was not really qualified to discuss, or write on, the subject since I “do not know” Sanskrit. One year later, in his above article (see quotation above), he again takes up the attack from that point. On the same grounds, he will be summarily dismissing my analysis of the evidence of the Avestan names, in this present volume, on the ground that I “do not know” Avestan.

[Significantly, in his mail to me dated 12/04/2002, Kazanas had written: “I changed my views about IAs and the RV date because facts compelled my mind (and your 1993 opus helped greatly)”. And now I am not even to be counted among writers who “advocated indigenism”.]

There is a saying in various Indian languages: “you can wake up a person who is asleep, but you cannot wake up a person who is only pretending to be asleep”. I will, accordingly, henceforward only be concentrating on waking up people who are asleep, and not waste my time in trying to wake up people from either the OIT side or the AIT side, who pretend to be asleep.

For various reasons, I feel it necessary to say a few words, and to give a few details, on errors and mistakes of different kinds in my earlier books:

1. The first mistake I made in my first book (TALAGERI 1993) was in having the book published in two versions. The paperback Voice of India edition, entitled “The Aryan Invasion Theory and Indian Nationalism”, was published slightly earlier, with a political section (Section 1 in that book) with three chapters. The hardcover Aditya Prakashan edition, entitled “The Aryan Invasion Theory: a Reappraisal”, was published a few months later without those three chapters (so that section 2 of the VOI edition became section 1 in the AP edition), and with a foreword by Dr. S R Rao.

The mistake did not lie in my making my political views clear (although, as I have clarified in the preface to the reprint in 2003, I would rephrase many of the sentences drastically if I wrote those chapters now; and my political views are more precisely expressed in TALAGERI 1997 and TALAGERI 2005a.): the chapters were absolutely necessary in order to clarify the political misuse being made of the AIT in Indian politics, society and academia, and the logic of those chapters is unanswerable.

The mistake lay in the fact that the different titles gave the impression that I had written two different books, and this left me prey to different emotions: embarrassment, when introduced (at that time) as the writer of two books, guilt when I thought of anyone possibly having purchased both books and wasted their money, and a bemused feeling when anyone earnestly assured me that they had read “both” my books.

In hindsight, the three chapters should have been published as a separate booklet.

2. In addition, the book contained quite a few printing errors and other minor errors in the VOI edition, only some of which were corrected in the AP edition later on in the year. The reprint of both the editions, in 2003, did not, however, correct these errors. For example, on p. 188 of the VOI edition, the sentence “which cannot occur in the medial position in a word” has been corrected in the AP edition, in 1993 itself, to “which cannot occur in the initial position in a word”, but was not yet corrected in the 2003 reprint of the VOI edition. However, most such errors were probably not even noticed by the readers, and in any case, did not make much material difference to the main thesis.

3. On some basic points, my second book, “The Rigveda: a Historical Analysis”, published in 2000, contained a drastic revision of some aspects of what I had written in my first book My first book dealt with all the different kinds of arguments on which the AIT is based, and hence was more important as a complete introduction to all aspects of the problem. But, the second book represented a more direct study of the literary evidence (which, in my first book was more based on second-hand references: Shendge, Bhargava, etc.), and also of the linguistic material, all of which led to a clearer perspective and some rethinking on many points.

The main rethinking, of course, was on the question of the geographical aspects: it was clear that the (almost) consensus view, that the Rigveda was composed in the Punjab, was totally without any basis in the geographical data in the Rigveda. In my first book, I had blindly accepted this view, but as actual examination of the data showed that the Rigveda was composed in the region of Kuruksetra, to the east of the Punjab, and that the Punjab was originally the home not of the Rigvedic Aryans (the Purus), but of their western neighbours, the proto-Iranians (the Anus). This fundamental shift in perspective led to many related corrections in the course of analysis of the Rigveda.

There are many other minor points, pertaining to the literary, linguistic and comparative mythological aspects of the problem, which have undergone rethinking or revision in my second book. I will not go into them here: suffice it to say that where the second book contradicts the first on any point, the second is to be taken as right.

To give one example, in my first book, in the course of pointing out the connections between the Teutonic Vanir and the Panis, I wrote: “It is not, as we have seen, merely a similarity in names (else we could have tried to identify the Greek Pan with the Panis due to the chance resemblance of the names), but in identity and incidents” (TALAGERI 1993:390). But further research, in the course of my second book, showed that there actually was an even closer correspondence, in identity and incidents, between the Greek Pan and the Panis than between the Teutonic Vanir and the Panis (see TALAGARI 2000:486-491).

Likewise, in my first book, I assumed (TALAGERI 1993:370, 375) THAT THE Druhyus in the Dasarajna battle hymns specifically referred to the Celtic and Italic branches (rather than, as I realized later, to the residual elements of a large amorphous group of branches to whom the Druis or Druids were the common priestly factor), and that these two branches were therefore present in the northwest at the time of the battle and were among the later emigrants. However, I realized later that they were among the earlier emigrants (TALAGERI 2000:260-282).

Even more important, I realized, on my own examination of the Rigvedic evidence, that while the Puranas were reliable insofar as some of their basic data was concerned, they were quite unreliable when it came to placing the different kings/rsis from different dynasties/tribes/clans in their relative chronological position vis-à-vis each other both within the dynastic lastis as well as between different dynastic lists, so that five different scholars who try to collate the lists arrive at five mutually incompatible versions of the dynastic lists. Historical or mythical persons (kings or rsis) whom the Rigveda indicates as belonging to the latest Rigvedic period are placed in the earliest periods in Puranic mythology, and some of them seem to be present in every period. Therefore, I decided that the Rigveda would be the sole authority for unraveling the ancient-most history of the Vedic Aryans, or the Indo-Iranians or Indo-Europeans in general, and that any data from any later text (including even post-Rigvedic Vedic literature itself) is absolutely null and void where it seems to contradict the evidence of the Rigveda. It will be noticed, in my last book as well as this present one, that I accept supporting evidence from any other text only when it helps to logically explain certain aspects of the Rigvedic data without contradicting other Rigvedic data.

| Bibliography | vii | |

| Preface | xv | |

| | ||

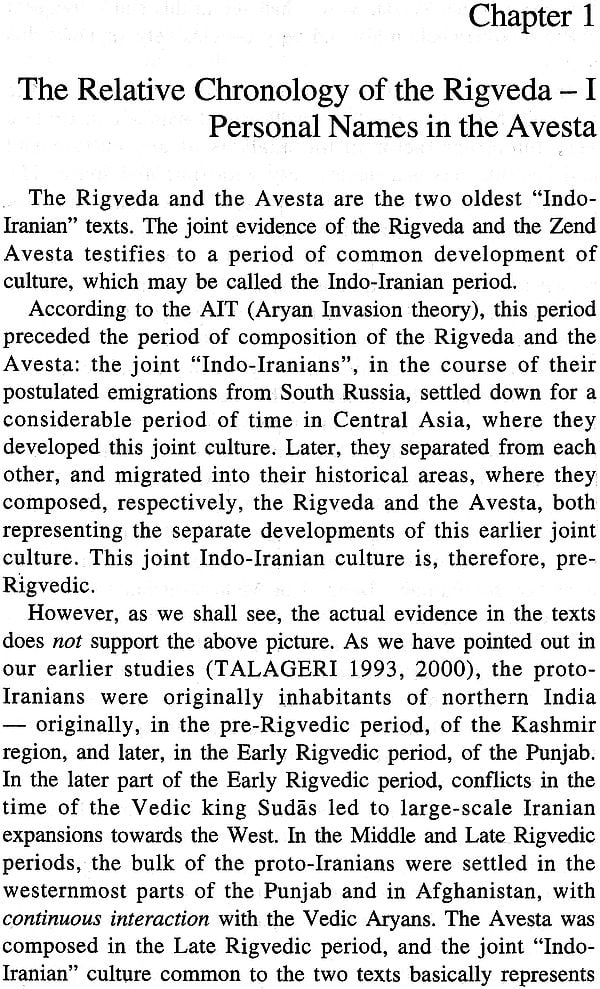

| Ch. 1. | The Relative Chronology of the Rigveda – I Personal Names in the Avesta | 3-53 |

| 1A. | The Early Rigveda – Rigvedic Names. | 6 |

| 1A-1. The Early Books. | 7 | |

| 1A-2. The Avesta. | 8 | |

| 1A-3. The Middle and Late Books. | 9 | |

| 1A-4. Certain Basic Words. | 12 | |

| 1B. The Early Rigveda – Iranian Names | 14 | |

| 1C. The Middle Rigveda | 16 | |

| 1D. The Late Rigveda. | 20 | |

| 1D-1. Composer Names. | 24 | |

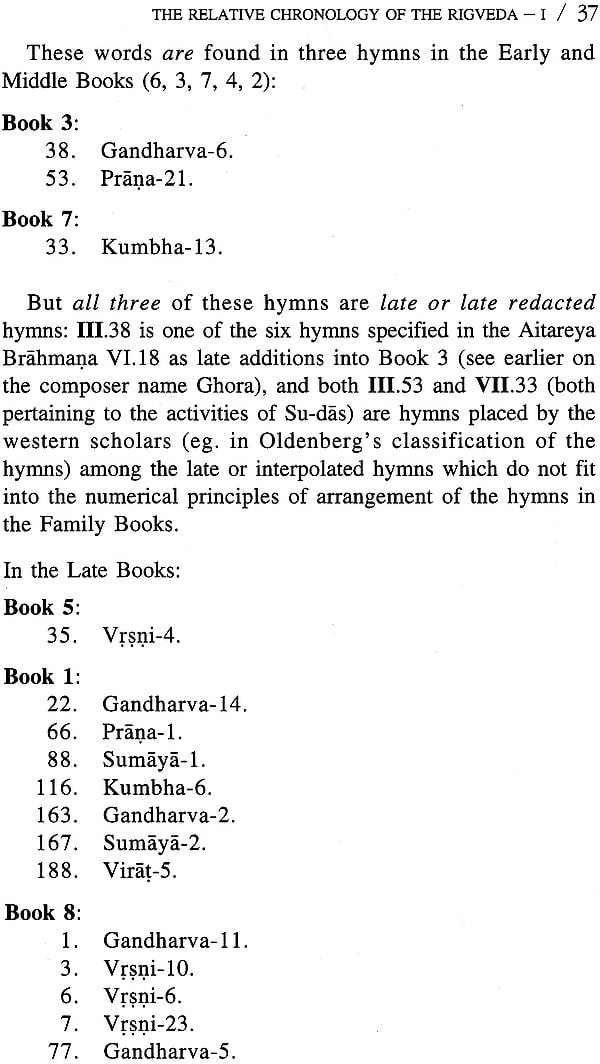

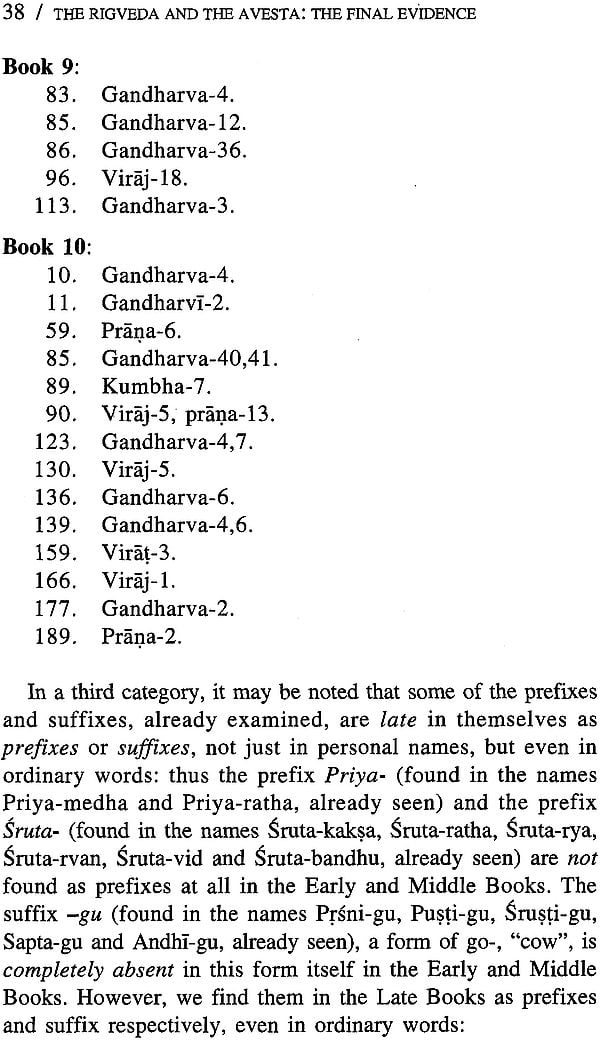

| 1D-2. Names in the Text. | 29 | |

| 1D-3. Other Words in the Text. | 35 | |

| 1E. Three “BMAC” words in Rigvedic Names | 40 | |

| 1F. What the Evidence Shows. | 43 | |

| 1G. Footnote: An “Iranian” Vasistha? | 49 | |

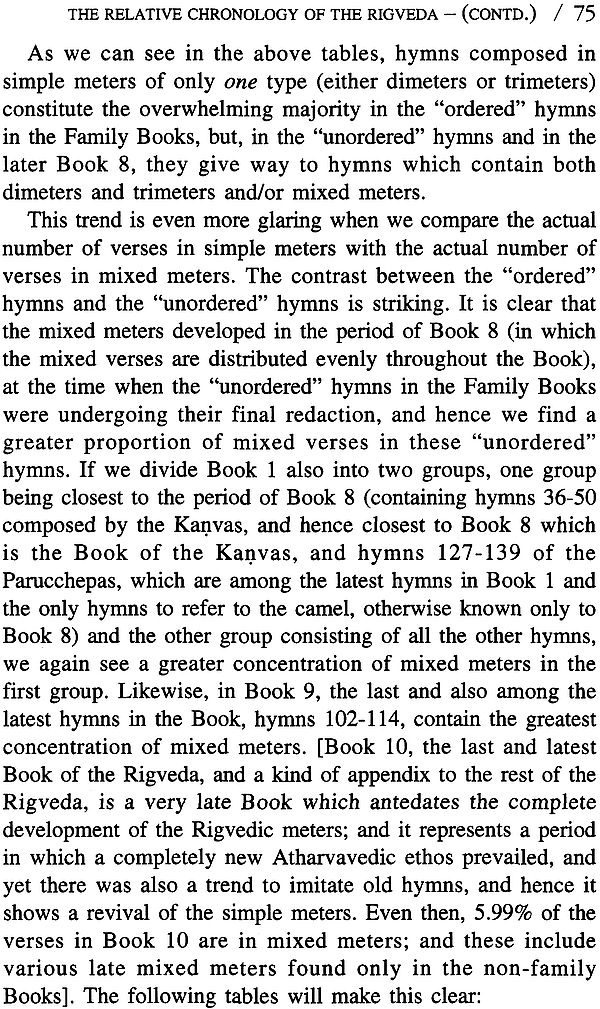

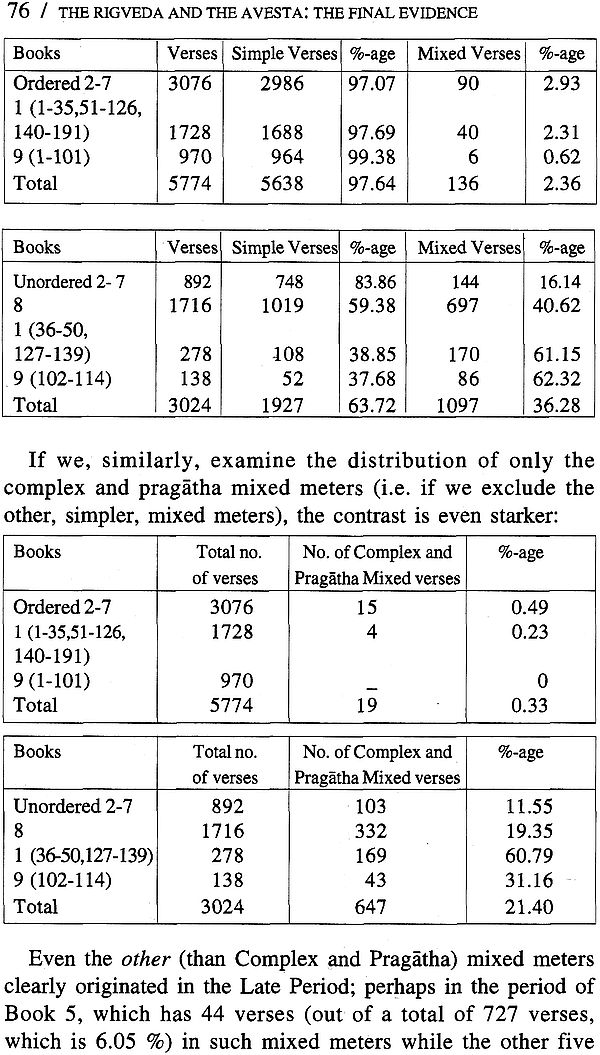

| Ch. 2. | The Relative Chronology of the Rigveda – I (contd). The Evidence of the Meters. | 54-80 |

| 2A. The Rigvedic Meters. | 54 | |

| 2B. The Chronology of the Dimeters. | 66 | |

| 2C. The Chronology of Other Meters. | 73 | |

| 2D. The Avestan Meters. | 77 | |

| Ch. 3. | The Geography of the RV. | 81-129 |

| 3A. The Eastern Region: The Sarasvati River and East. | 84 | |

| 3B. The Western region: The Indus River and West. | 88 | |

| 3C. The Central Region: Between the Sarasvati and the Indus. | 92 | |

| 3D. Summary of the Data. | 95 | |

| 3E. Appendix 1: Other Geographical Evidence | 98 | |

| 3E-1. Climate and Topography | 99 | |

| 3E-2. Trees and Wood. | 101 | |

| 3E-3. Rice and Wheat. | 102 | |

| 3E-4. The Traditional Vedic Attitude towards the Northwest. | 104 | |

| 3F. Appendix 2. The Topsy-turvy Logic of AIT Geography. | 107 | |

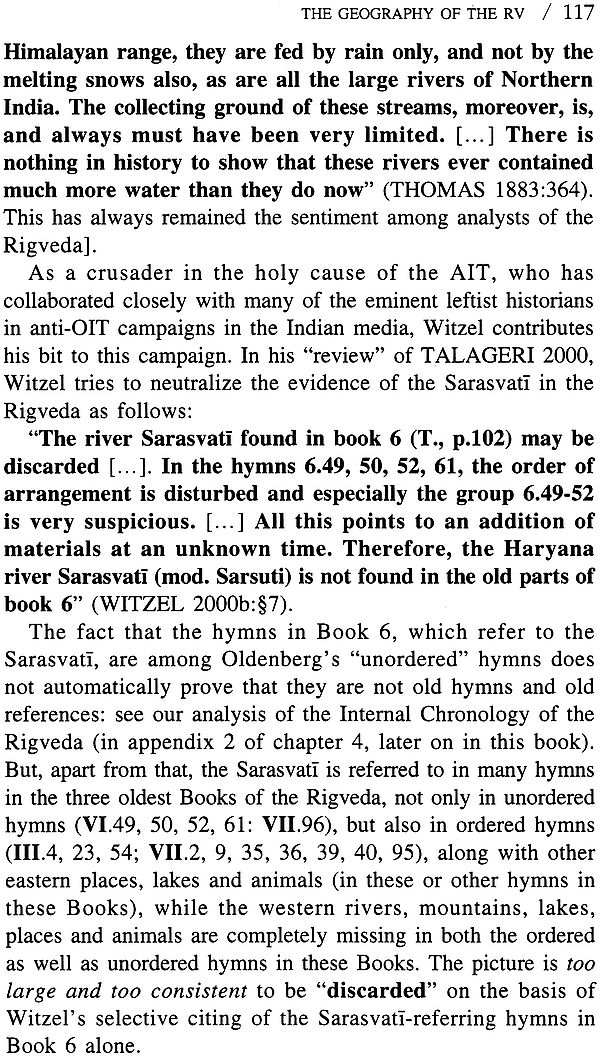

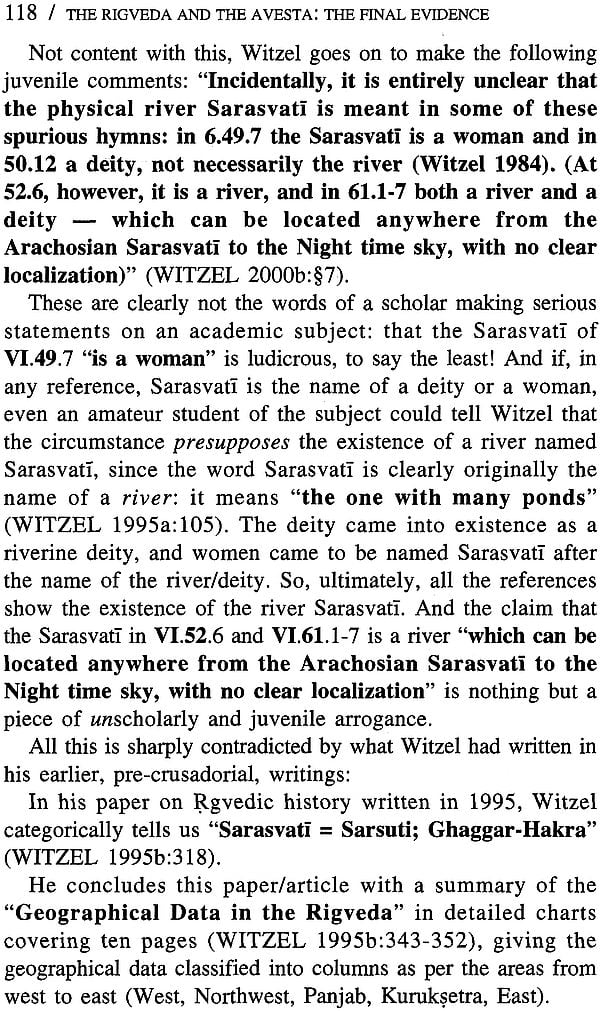

| 3F-1. The Sarasvati. | 115 | |

| 3F-2. The Ganga. | 122 | |

| Ch. 4. | The Internal Chronology of the Rigveda | 130-167 |

| 4A. The Late Books as per the Western Scholars Themselves. | 131 | |

| 4B. Can This Evidence be Refuted? | 135 | |

| 4C. Appendix 1: The Internal Order of the Early and Middle Books. | 142 | |

| 4C-1. The Early vis-à-vis the Middle Books. | 144 | |

| 4C-2. The Early Books. | 146 | |

| 4C-3. The Middle Books. | 147 | |

| 4D. Appendix 2: “Late” Hymns | 149 | |

| 4D-1. Facts. | 150 | |

| 4D-2. Testimony. | 151 | |

| 4D-3. Deductions. | 152 | |

| 4D-4. Speculations. | 163 | |

| Ch. 5. | The Relative Chronology of the Rigveda – II The Mitanni Evidence. | 168-183 |

| 5A. Witzel’s Fraudulent Arguments. | 168 | |

| 5B. The Actual Evidence. | 175 | |

| 5C. Footnote: Edward W. Hopkins. | 180 | |

| Ch. 6. | The Absolute Chronology of the Rigveda. | 184-201 |

| 6A. The Mitanni Evidence. | 186 | |

| 6B. The Additional Chronological Evidence. | 189 | |

| 6C. The Implications. | 200 | |

| | ||

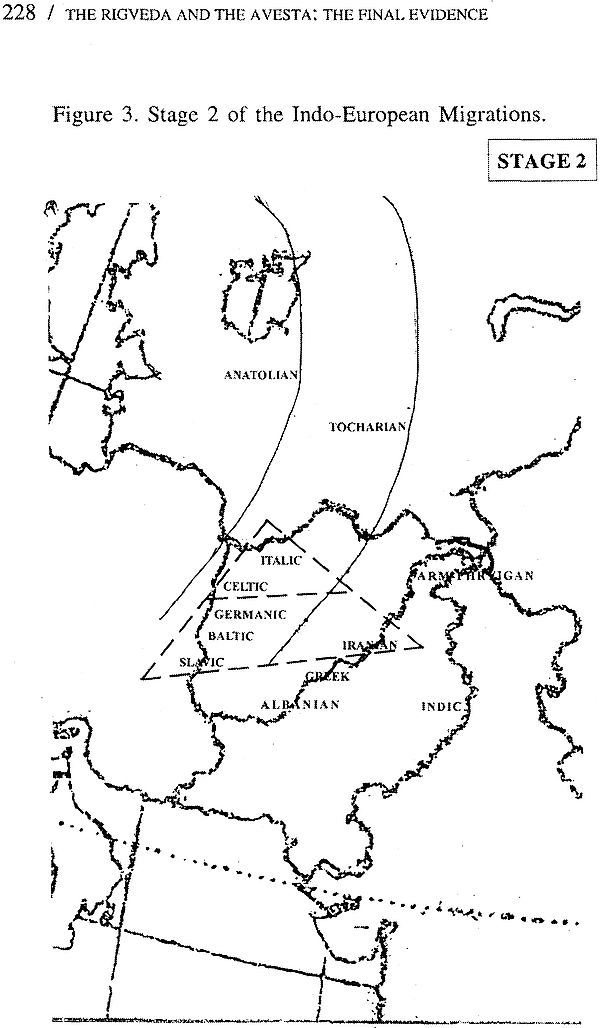

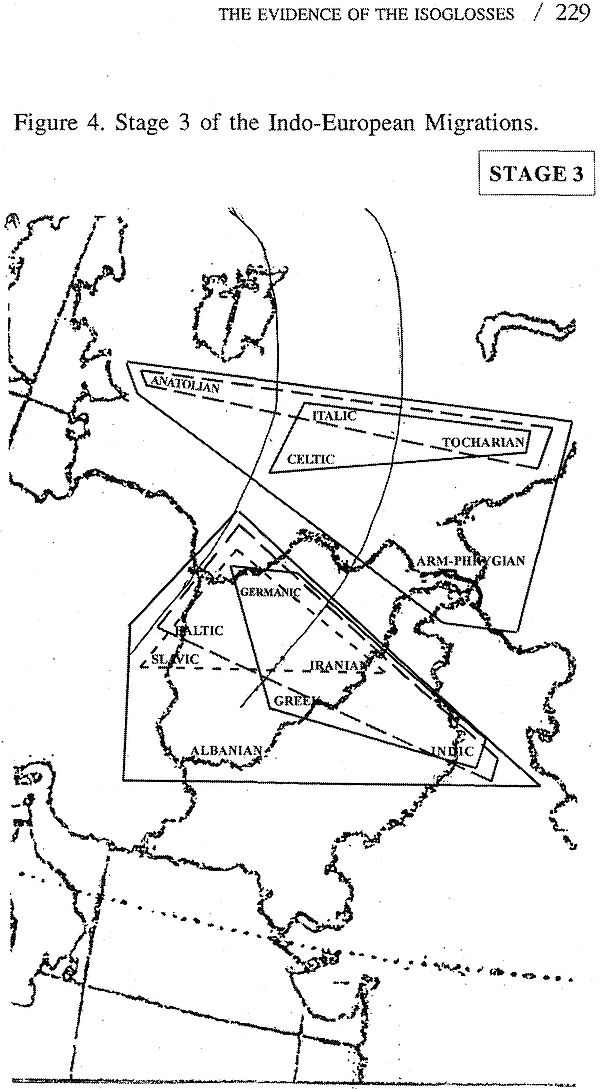

| Ch. 7. | The Evidence of the Isoglosses | 205-307 |

| 7A. Hock’s Linguistic Case. | 213 | |

| 7B. Hock’s Case Examined. | 218 | |

| 7C. The Evidence of the Isogosses. | 223 | |

| 7D. The Evidence in Perspective | 236 | |

| 7D-1. The Early Dialects. | 236 | |

| 7D-2. The European Dialects. | 240 | |

| 7D-3. The Last Dialects. | 251 | |

| 7E. The Last Two of the Last Dialects. | 258 | |

| 7E-1. The Textual Evidence. | 259 | |

| 7E-2. The Uralic Evidence. | 273 | |

| 7F. The Linguistic Roots in India. | 277 | |

| 7G. Appendix: Witzel’s Linguistic Arguments against the OIT. | 290 | |

| Ch. 8. | The Archaeological Case | 308-354 |

| 8A. The Archaeological Case Against the AIT. | 312 | |

| 8B. The Case for the OIT. | 332 | |

| 8B-1. The PGW (painted grey ware) Culture as the Vedic Culture. | 332 | |

| 8B-2. The Harappan Civilization as the Rigvedic Culture. | 333 | |

| 8B-3. The Indo-European Emigrations. | 345 | |

| 8C. The Importance of the Rigveda. | 347 | |

| Postscript: Identities Past and Present | 355-370 | |

| Index | 371-375 |