The Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam (Explained)

Book Specification

| Item Code: | NAE958 |

| Author: | Paramhansa Yogananda and Swami Kriyananda |

| Publisher: | Ananda Sangha Publications, Gurgaon |

| Language: | English |

| Edition: | 2008 |

| ISBN: | 9788189430597 |

| Pages: | 399 (10 B/W Illustrations) |

| Cover: | Paperback |

| Other Details | 9.0 inch X 6.0 inch |

| Weight | 450 gm |

Book Description

Omar Khayyam’s famous poem, the Rubaiyat of omar Khayyam is loved by westerners as a hymn of praise to sensual delight. In the east his quatrains enjoy a very different reputation: they are known as a deep allegory of the soul romance with God. Even there however the knowing is based on who and what omar Khayyam was: a sage and mystic. As for what his quatrains actually mean most of them have remained a mystery in the east as much as in the west.

Now after more than eight centuries paramhansa yogananda one of the great mystics of our time a master of yoga and the author of the spiritual classic Autobiography of a yogi explains the mystery behind omar famous poem. In Yogananda introduction he wrote:

I suddenly beheld the walls of its outer meaning crumble away. The vast inner fortress of golden spiritual treasures stood open to y gaze.

This book contains the essence of that great revelation. Unavailable in book form since its first penning over 60 years ago the Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam explained available at last edited by one of yogananda close disciples a bestselling author in his own right swami kriyananda.

Paramhansa Yogannada was one of the best known spiritual teachers of the twentieth century. His autobiography of a yogi, published in 1946 and printed in more than 20 languages has touched the hearts of millions and has been rated the best-selling autobiography of all time. Yogananda was the first true yoga master to settle in the west. He lived in America from 1920 until his death in 1952. During the early years he crisscrossed the united states extensively on lecture tours during which many thousands thronged to hear the yoga master form India. He spent his later life teachings writing and directing an expanding worldwide work. Today hundreds of thousands of seekers around the world consider themselves to be his disciples.

Swami kriyananda (J. Donald Walter) has been a close direct disciple of paramhansa yogananda since 1948. In 1950, yoganada gave him the task of editing his explanation of omar Khayyam Rubiayat a responsibility for which his disciple spent 44 years preparing himself. Kriyananda is the founder of Ananda sangha a worldwide organization which disseminates yoganada teaching. In 1968 he founded a spiritual cooperative community which has expanded to eight communities and ashrams in the U.S., Europe, and India. He has written over 90 books and 400 pieces written over 90 books and 400 pieces of uplifting music. He resides in India.

I was giving a lecture on this book in Sydney, Australia, in the spring of 1997 at the Theosophical Society. Following my talk, a man raised his hand and said, "I fail to see a correlation between this stanza"-he named it-"and Yogananda's explanation of it."

"Several times during the editing process," I replied, "I found that there didn't seem at first to be a clear correlation between the poem and Yogananda's explanation. On fuller reflection, however, I always discovered that the correlation existed, and that it was profound."

At that point a woman in the audience raised her hand to say, "I am from Iran,-and can read ancient Persian. I l-mow the passage to which the gentleman is referring, and I wish to say that, although the correlation with Edward Fitz Gerald's translation may seem tenuous, what Yogananda has written is exactly true to the original Persian."

Her words gave strong support to my own growing conviction as I was editing this book that Yogananda had tuned in to Omar Khayyam's consciousness, not to the words merely, and that he had explained the true, inner meaning of this great poem. Paramhansa Yogananda did not know Persian. What he did, by his amazing depth of insight, was allow Omar Khayyam to speak through him directly.

He did this again when he wrote his commentaries on the bhagavad Gita. As he said to me in 1950 I now know why my great guru never wanted me to read other interpretations of the Gita. It was to keep me from feeling I must relate to their thoughts. What I did rather was ask byasa himself [the author of that great scripture] to write these commentaries through me.

It has become clear to me that paramhansa yogananda was able to penetrate far beneath the words of scripture and to discern the real meaning underlying them. The words themselves especially when they are translated can only be abstractions of that meaning. His explanation were never based on intellectual but always on the deep indeed cosmic perceptions of intuitions.

Who has not heard these lines? Like shakespeare’s tomorrow and tomorrow and tomorrow they have become part o our language almost idioms. Even people who have never heard of the Rubaiyat of omar Khayyam are familiar with many lines from his poem like the sailor who after attending a performance of hamlet for the first time exclaimed in amazement to a friend Did you hear all those platitudes.

Westerners believe and have in fact been old so again and again that the rubaiyat is a love poem one written in celebration of earthly joys. Such is not the case as paramahansa yoganada makes thrillingly clear in this book. Throughout the east omar Khayyam is recognizes as a mystic and his poem accepted as a deep spiritual allegory too deep for ordinary comprehension.

Even as a love poem and celebration of earthly pleasures most of it defies comprehension. As I have written in an editorial comment at the end of one of the commentaries it is like great music: it speaks powerfully to our deepest nature even when its meanings elude us. It is a love poem in a sense both human and divine for when its inner meaning are unveiled yogananda shows how deeply meaningful the quatrains are also in their outward human application. Omark Khayyam was a deep mystic not a hedonist but his mysticism was for all that warmly human.

I’ll say something about him and about his translator Edward fitz Gerald in the next section. First however (since mnay reader will already know their story) there are to more immediate questions to address who was paramhansa yogandsa and why this commentary? The second question I’ll leave to ygananda himself to answer let me endeavor briefly to do justice to the first.

Parmahansa yogananda was one of the great spiritual lights of the twentieth century. His autobiography of a yogi first published in 1946 has come to be ranked among the best selling autobiographies of all time and continues. In Italy as recently as three year ago it was the number one best seller in the non-fiction category. For a book that is quite a records.

Paramhansa Yogananda was one of the great spiritual lights of the twentieth century. His autobiography of a yogi, first published in 1946 has come to be ranked among the best selling autobiographies of all time and continues to appear on best seller lists in various countries. In Italy as recently as three years ago it was the number one best seller in the non-fiction category. For a book that has been in print for nearly fifth years that is quite a record.

Paramhansa yogananda author, poet, lecturer, spiritual, teacher, guide and friend to countless thousands was born in Indian in 1893. He was sent by his spiritual teachers to America in 1920 and remained domiciled in this country lecturing to hundreds of thousand across the land for the remainder of his life until his passing in 1952. He founded a known and respected organization self realization fellowship headquartered in los angles California. The message he delivered was non-sectarian and universal. The very name he gave his organization was intended to highlight universal principles; the organization was not created to be a new sect Paramhansa Yogananda was great not so much in a worldly sense as for his stature as a human being and as a saint.

No man it has been said is great in the eyes of his own valet. To this adage Yogananda was an outstanding exception. Those who held him in the highest teem were those who knew him life and was continually amazed to note that he displayed none even of those perfectly normal foibles which one expects to find in the greatest of human beings. If he didn’t meet my expectations of him as happened sometimes I always found that it was because he exceeded those expectations.

His charity compassion unshakable calmness, loving friendship to all delightful sense of humor and deep insight into human nature were such as to leave me constantly amazed. In my own autobiography, the path which describes what it was like to live with him I wrote: yogananda wore his wisdom without the slightest affectation like a comfortable old jacket that one has been wearing for years. Again in that book I wrote in some ways it was I think his utter respect for other that impressed me the most deeply. It always amazed me that one whose wisdom and power inspired so much awe in other could be at the same time so humbly respectful to everyone.

Such was the man to whom Destiny as Omar Khayyam would have put it gave the task of explaining the rubaiyat if omar work has over been explained in depth before I am not aware of it. Yogananda was in any case the perfect person for the job. His broad mindedness his deeply sensitive poetic nature his keen sense of comedy his non dogmatic view of religion all these combined with absolute devotion to the highest Ruth made him the best imaginable person to confront the challenge of unraveling the centuries mystery that is Omar Khayyam. For in a very real sense Yogananda shared Omar vision of life. His attunement with the poet is manifested throughout these commentaries.

In 1950 Yogananda axed me to work on editing his writing beginnings with this book which had first appeared in serialized form in Inner culture Magazine, 1937-1944. He prefaced his request with a statement that could hardly have failed to make an impression on me. I asked divine mother he said referring to that aspect of God to which he normally prayed whom I should take with me for this work and your face appeared. Twice more I prayed to make sure and each time your face appeared. I did my best at that time. I was only twenty three years old however and woefully inexperienced in matter both literary and spiritual. Divine mother certainly and yogananda man of wisdom that he was could not but have been aware that the task of editing his words was then quite beyond my capabilities obviously a different timing was involved here though my guru made it seem as though I was to do the job as soon as possible. I’ come to realize that their now meant now in this life and not now in 1950! In fact my guru was looking far into the future for he knew that his own remaining years on earth were few.

Since 1950, forty-four years have passed. Now, with some measure of literary experience behind me as author of more than fifty books and with these intervening years of inner growth in understanding I think I may diffidently claim at least this much for my abilities that I am as ready now as I’ll ever be.’

Reader may consider it strange that the words of a wise man should require editing at all. People often confuse wisdom with intellectual learning or with the pleasure some deep thinkers find in making clearly reasoned explanations. True wisdom however is intuitive; it is an arrow that files straight to its mark while the intellect lumbers with labored breathing far behind. An example of such insight was Einstein firs perception of the law of relativity which came to him in a flash. He had to work year before he could tailor the rational clothing for his intuitive perception that would make it presentable to other scientist.

An I reflect on the men and women of great spiritual wisdom whom it has been my good fortune in life to meet it occurs to me that all of them spoke from higher than rational perception. Their manner of self-expression was succinct. Seldom did they explain their ideas at length. It was as though they wanted their listeners to rise and meet them on a higher level of cognition.

Their wisdom was non-verbal. Where most people think in word true sages much of the time are not thinking at all: they are perceiving. I don’t mean to say they are incapable of normal reasoning even of brilliant reasoning. In fact I have found them to be much clearer in this respect than most people. But the slow processes of ratiocination represent for them rather a step away from clarity into the tortuous labyrinth of pros and cons.

Yogananda was a sage of intuitive wisdom who disciplined him mind out of compassion for people of slower understanding to accept the plodding process of common sense and to trudge the twisting byways of ordinary human reasoning. His consciousness soared more naturally however in skies of divine ecstasy. His preferred way of expressing himself was to touch lightly on appoint inviting others to meet him on his own level. It was to us his disciples usually that the left the task of expanding on or explaining the truths he presented in condensed from in his writings.

I did my best throughout this work not to change a single thought and never to introduces any ideas of my own though the logical flow made it necessary sometimes to create a bridge from one idea to the next. My job as editor has been to facilitate the flow of the author ideas. Occasionally while working on the commentary for a particular stanza some idea has occurred to me that it seemed to me might make a helpful addition to the book. In such cases I put that idea at the end of the commentary under the heading editorial comment.

I hope dear reader that you will share with me some of the enthusiasm I felt for this work forty four years ago when I first tried so ineffectually then to edit it. The enthusiasm has remained with me all these years. For this work is I believe one of the greatest spiritual books ever written. And my humble efforts as its editor comprise for me thus far the single most important labor of my life.

Long ago in India I met a hoary Persian poet who told me that the poetry of Persia often has two meanings, one inner and one outer. I remember the great satisfaction I derived from his explanation of the double significance of several Persian poems.

One day, as I was deeply concentrated on the pages of Omar Khayyam's Rubaiyat, I suddenly beheld the walls of its outer meanings crumble away. Lo! vast inner meanings opened like a golden treasure house before my gaze.

Such profound spiritual treatises, by some mysterious divine law, do not disappear from the earth even after centuries of neglect or misunderstanding. Such is the case with The Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam. Not even in Persia is Omar's philosophy deeply understood. Few or none have plumbed it to the depths that I have tried to present here. Because of the spiritual power inherent in this poem, it has withstood the ravages of time the misinterpretations of intellectual scholars, and the distortions of many translators. Ever pristine in its beauty, simplicity, and wisdom, it has remained an untouched and unpalatable shrine to which truth-seekers of all faiths, and of no faith, can go for divine solace and understanding.

In Persia, Omar Khayyam has always been recognized as a highly advanced mystic and spiritual teacher. His rubaiyat have been revered as an inspired Sufi scripture. "The first great Sufi writer was Omar Khayyam," writes Professor Charles F Horne in the Introduction to the Rubaiyat, which appears in Vol. VIII of "The Sacred Books and Early Literature of the East" series." "Unfortunately," he continues, "Omar, by a very large number of Western readers, has come to be regarded as a rather erotic pagan poet, a drunkard interested only in wine and earthly pleasure. This is typical of the confusion that exists on the entire subject of Sufism. The West has insisted on judging Omar from its own viewpoint. But if we are to understand the East at all, we must try to see how is' own people look upon its wittings. It comes as a surprise to many Westerners when they are told that in Persia itself there is no dispute whatever about Omar's verses and the spiritual depth of their meaning. He is accepted quite simply as a great religious poet.

"What then becomes of all [Omar's] passionate praise of wine and love?" demands Professor Horne. "These are merely the thoroughly established metaphors of Sufism; the wine is the joy of the spirit, and the love is the rapturous devotion to God ....

"Omar rather veiled than displayed his knowledge. That such a man would be regarded by the Western world as an idle reveler is absurd. Such wisdom united to such shallowness is self-contradictory."

Omar and other Sufi poets used popular similes and pictured the ordinary joys of life so that the worldly man could compare mundane pleasures with the superior joys experienced in the spiritual life. To the man who drinks wine in order to forget, temporarily, the unbearable sorrows and trials of his life, Omar offers a delightful alternative: the nectar of divine ecstasy, which leads to divine enlightenment, thereby obliterating human woe permanently. Surely Omar did not go through the labor of writing so many exquisite verses merely to "inspire" people to escape sorrow by drugging their senses with alcohol!

J.B. Nicolas, whose French translation of 464 rubaiyat (quatrains) appeared in 1867, a few years after Edward FitzGerald's first edition, opposed FitzGerald's view that Omar was a materialist. FitzGerald refers to this contradiction in the introduction to his own second edition, thus:

M. Nicolas, whose edition has reminded me of several things, and instructed me in others, does not consider Omar to be the material epicurean that I have literally taken him for, but a mystic, shadowing the Deity under the figure of wine, wine-bearer, etc., as Hafiz is supposed to do; in short, a Sufi poet like Hafiz and the rest .... As there is some traditional presumption, and certainly the opinion of some learned men, in favor of Omar's being a Sufi-even some- thing of a saint-those who please may so interpret his wine and cup-bearer." FitzGerald's difficulty lay in the fact that, although some of the stanzas clearly lend themselves to a spiritual interpretation, most of the others seemed to him to defy any but a materialistic one.

In plain fact, Omar distinctly states that wine symbolizes the intoxication of divine love and joy. Many of his stanzas are so purely spiritual that hardly any material meaning can be drawn from them, as for instance in quatrains Forty, Forty-four, Fifty, and Sixty-six. The inner meaning of many other stanzas is more difficult to discern, but it is there nevertheless, and stands clearly revealed in the light of inner vision.

With the help of a Persian scholar, I translated the original rubaiyat into English. But I found that, though literally translated, they lacked the fiery spirit of Omar's original. After I compared that translation with FitzGerald's, I realized that FitzGerald had been divinely inspired to catch exactly, in gloriously musical English, the soul of Omar's writings.

Therefore I decided to interpret the inner hidden meaning of Omar verses from fitz Gerald Translation rather than from my own or from any other that I had read.

Fitz Gerald prepared five different edition of the Rubaiyt. For my explanation I have chosen the first as a person first expression being spontaneous natural and he closest to true soul inspiration is often the deepest and purest.

As I worked on the spiritual explanation of the Rubaiyat I found it taking me into an endless labyrinth of truth until I was rapturously lost in wonderment. The veiling of Omar metaphysical and practical philosophy in these verses reminds me of the revelation of St. John the Divine indeed the Rubaiyat might justly be called the revelation of Omar Khayyam.

| Editor's Preface to the second edition | IX | |

| Editor's Preface | XI | |

| Omar Khayyam an Edward fitzGerald | XVII | |

| Introduction by Paramhansa yogananda | XX | |

| Stanza | ||

| One | A wake! For morning in the bowl of night | 2 |

| Two | Dreaming when dawn’s left hand was in the sky | 6 |

| Three | And as the cock crew | 10 |

| Four | Now the new year reviving old desires | 16 |

| Five | Iram indeed is gone with all its rose | 20 |

| Six | And David lips are lock’t | 24 |

| Seven | Come, fill the cup and in the fire of spring | 28 |

| Eight | And look a thousand blossoms with the day | 32 |

| Nine | But come with old Khayyam and leave the lot | 36 |

| Ten | With me along some strip of herbage strown | 42 |

| Eleven | Here with a loaf of bread beneath the bough | 48 |

| Twelve | How sweet is mortal savranty | 54 |

| Thirteen | Look to the rose that blows about us | 58 |

| Fourteen | The worldly hope men set their hearts upon | 64 |

| Fifteen | And those who husbanded the Golden Grain | 70 |

| Sixteen | Think in this batter caravanserai | 74 |

| Seventeen | They say the lion and the lizard keep | 78 |

| Eighteen | I sometimes think that never below so red | 82 |

| Nineteen | And this delightful herbs whose tender green | 86 |

| Twenty | Ah, my beloved fill the cup | 90 |

| Twenty One | Lo! Some we loved the loveliest and best | 94 |

| Twenty Two | And we that now make merry in the room | 98 |

| Twenty Three | Ah, make the most of what we yet may spend | 102 |

| Twenty Four | Alike for those who for today prepare | 106 |

| Twenty Five | Why all the saints and sages | 110 |

| Twenty Six | Oh, come with old Khayyam and leave the wise | 114 |

| Twenty Seven | Myself when young did eagerly frequent | 118 |

| Twenty Eight | With them the seed of wisdom did I sow | 122 |

| Twenty Nine | Into this universe and why not knowing | 126 |

| Thirty | What without asking hither hurried whence? | 130 |

| Thirty One | Up from centre though the seventh gate | 134 |

| Thirty Two | There was a door to which I found no key | 148 |

| Thirty Three | The to the rolling heav’n itself I cried | 152 |

| Thirty Four | Then to this earthen bowl did I adjourn | 156 |

| Thirty Five | I think the vessel that with fugitive articulation answer’d | 162 |

| Thirty Six | For in the market place one dusk of day | 168 |

| Thirty Seven | Ah, fill the cup: what boos it to repeat | 172 |

| Thirty Eight | One moment in Annihilation waste | 176 |

| Thirty Nine | How long, how long, in infinite pursuit | 182 |

| Forty | You know my friend how long since in my house | 186 |

| Forty One | For is and is not though with rule and line | 190 |

| Forty Two | And lately by the tavern door agape | 194 |

| Forty Three | The grape that can with logic absolute | 198 |

| Forty Four | The mighty Mahmud the victorious lord | 202 |

| Forty Five | But leave the wise to wrangle and with me | 206 |

| Forty Six | Tis nothing but a magic shadow show | 210 |

| Forty Seven | And if the wine your drink the lip you press | 216 |

| Forty Eight | While the rose blows along the river brink | 220 |

| Forty Nine | Tis all a chequer-board of nights and days | 224 |

| Fifty | The ball no question make of Ayes or Noes | 230 |

| Fifty One | The moving finger writes: and having writ | 236 |

| Fifty Two | And that inverted bowl we call the sky | 242 |

| Fifty Three | With earth first clay they did the last man knead | 246 |

| Fifty Four | I tell thee this when stating from the goal | 252 |

| Fifty Five | The vine had struck a fibre | 252 |

| Fifty Six | And this I know: whether the one true light | 262 |

| Fifty Seven | Oh thou, who didst with pitfall and with gin | 266 |

| Fifty Eight | Oh thou, who man of baser earth didst make | 272 |

| Fifty Ninth | Listen again. One evening at the close of ramazan | 278 |

| Sixty | And strange to tell among the earthen lot | 282 |

| Sixty One | Then said another surely not in vain | 286 |

| Sixty Two | Another said why ne’er a peevish boy | 292 |

| Sixty Three | None answer this but after silence | 296 |

| Sixty Four | Said one another with a log drawn sigh | 300 |

| Sixty Five | Then said another a long drawn sigh | 304 |

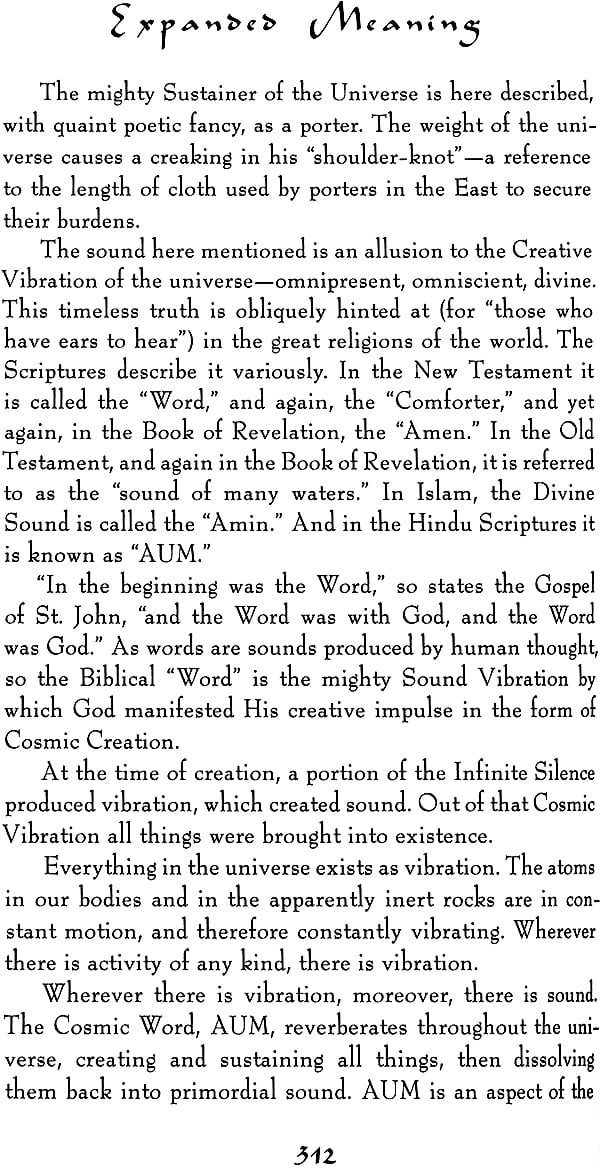

| Sixty Six | So while the vessels one by one were speaking | 310 |

| Sixty Seven | Ah with the grape my fading life provide | 316 |

| Sixty Eight | That ev’n my buried ahesh such a snare | 320 |

| Sixty Nine | Indeed the idols I have loved so long | 324 |

| Seventy | Indeed, indeed repentance oft before I sware | 328 |

| Seventy One | And much as wine has play’d the infidel | 332 |

| Seventy Two | Alas that spring should vanish with the rose | 336 |

| Seventy Three | Ah love could thou and I with fate conspire | 340 |

| Seventy Four | Ah moon of my delight who know st no wane | 348 |

| Seventy Five | And when they self with shining foot shall pass | 352 |

| About the editor | 357 | |

| Further exploration | 359 |