The Silk Road Fabrics (The Stein Collection in the National Museum of India)

Book Specification

| Item Code: | NAP935 |

| Author: | ArputhaRani Sengupta |

| Publisher: | D. K. Printworld Pvt. Ltd. |

| Language: | English |

| Edition: | 2018 |

| ISBN: | 9788124609217 |

| Pages: | 294 (Throughout Color & B/W Illustrations) |

| Cover: | HARDCOVER |

| Other Details | 11.50 X 9.50 inch |

| Weight | 1.60 kg |

Book Description

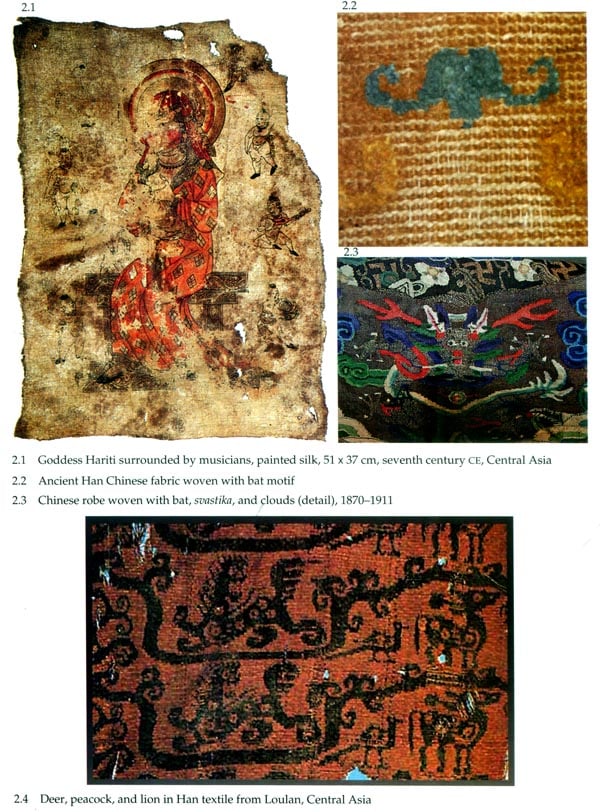

Besides Stein's assemblage, Central Asian burial textile in the State Hermitage Museum in Leningrad is a major collection. Our knowledge of antique textile comes mainly from these museum pieces. Archaeological textile studies are an important source of information for anthropological and technological inquiry. At Copenhagen John Becker's reconstruction of Han Pattern and Loom resulted in the instructive A Practical Study of the Development of Weaving Techniques in China, Western Asia and Europe first published in 1986. Moreover color is the single most remarkable quality of any Central Asian textile. The sources of natural dyes and method of fixing hold a number of clues. The discovery of heritage textiles from Central Asia and China is comparatively recent. Even so, the admirable work of scholars and ever-growing demand in a collector's market have increased the number of publications on ancient textiles in museums and art galleries. The Metropolitan Museum of Art and The Cleveland Museum of Art came together and held an exhibition of the Asian textiles dating from the eighth to the early fifteenth century CEo The catalog When Silk Was Gold: Central Asian and Chinese Textiles published in 1997 by the collaborating museums admirably fulfilled a function in this category. Since 1950 the second period in archaeological excavation of textiles was undertaken by the People's Republic of China in well over 100 burial sites in south central China, Mangolia and Central Asia. In collaboration with worldwide institutions The Silk Road International Dunhuang Project documentation makes research in this area infinitely expandable.

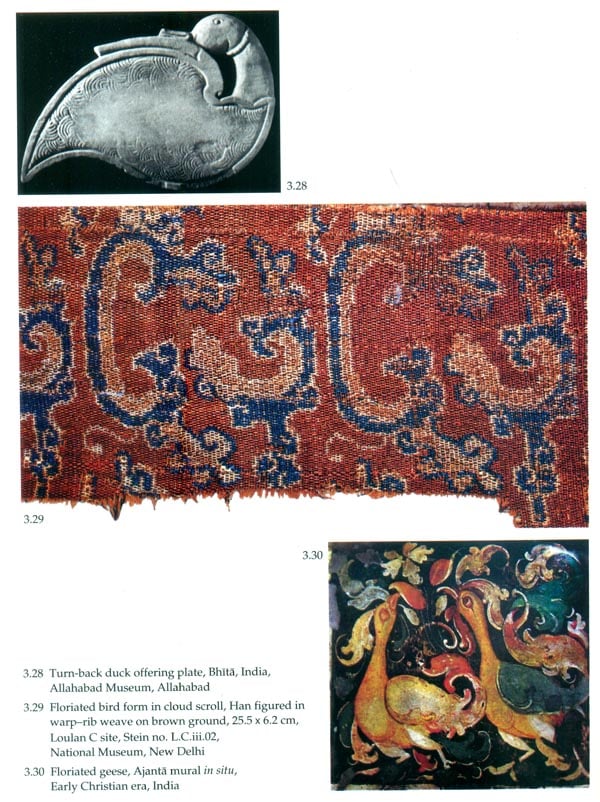

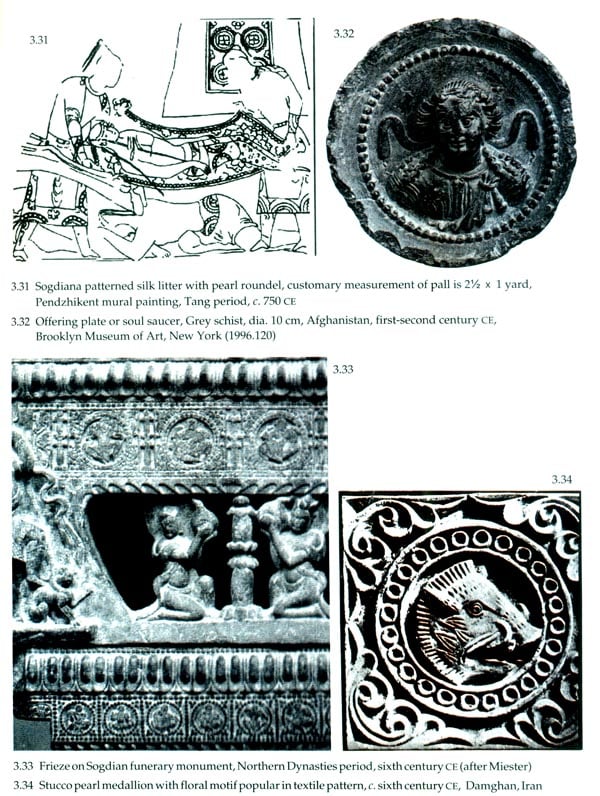

The mysterious innovations in silk weaving in Central Asia are astonishing in the light of the fact that the technology was known for centuries in West Asia. Chinese Central Asia without the proto-weaving techniques of twining and plaiting suddenly accomplished sericulture and professional silk weaving. The fully developed and technically unsurpassed figure weaves from a landlocked region defined by its deserts, inhospitable climate and limited rainfall are rather mysterious. The greatest advantage was the native mulberry bush in the rearing of Bombyx mori for the finest and longest of silken thread. The convergence of sericulture and silk weaving had definitive form and function. Exposed to freezing nights and searing heat during the day, graves yielded stunning silk furnishing symptomatic of a drastic change in funerary customs. Ethno- archaeology not only reveals technical excellence in weaving but also offers proof of faith in afterlife. The discovery of these historic fabrics preserved in Japan, Africa and Europe exposes their identity and character. In addition, the textile designs actually have a notable function in Parthian and Greco-Buddhist architectural reliefs in Persia and South Asia. Riboud's discussion on Han dynasty textiles compares the animal style to early Indian sculpture. The shared motifs in mortuary art indicate that a full exploration in this direction is a challenging but a rewarding task. When that cultural context is not acknowledged a great amount of historical realism is also lost. To address this problem consideration of religious symbolism, funerary customs and folklore inherent to the burial silk and artifacts recovered along the Silk Road is essential.

As the most preferred funerary goods silk worth its weight in gold is the most significant factor in the trade along the Silk Road. Caught in the dynamics of history are the geopolitical plot and the emerging distinction between China, Inner Asia and Eurasia in the geographical sense of the term. It was not yet populated by either self- contained or self-defined nationalities. Ethnically and culturally indistinct nationalities intermingled in the Crossroads of Asia. As the carriers of ideas and commodities and also religions, merchants and travelers not only connected Mongolia-China with Syria, Turkey, and Egypt but several of them even adopted new homelands. Commercial contacts have a longer lasting life and an immense potential to cement the bonds between various countries. As a result, the Greco-Buddhist reliquary cult in South Asia flourished precisely due to the lucrative silk trade with Rome. It is in this light that several of the figured textiles will be viewed in terms of their affirmed function. One of the astonishing by-products of the Silk Road is the jade garment. Depending on the station of the person buried, body suits made of pieces of jade are exceptional. These are fashioned mostly with square or rectangular and occasionally triangular, trapezoid and rhomboid plaques knitted together by gold, silver or copper wire. The most fabulous among these is the jade burial suit at the Mausoleum Museum of the Nanyue King in Cuangzhou. The "patchwork suit" is made of 2,291 pieces of jade pieces connected by red silk thread or silk ribbon overlapping the edges of the plaques. The world's oldest textile printing blocks in bronze from this Han tomb are also part of the Nanyue culture. Indicating that Guangzhou in the ancient Silk Route was exposed to diverse influences, the tomb contained in addition to extraordinary Chinese burial goods, five African elephant tusks, frankincense and a silver box from Persia.

Patchwork robe refers to clothing pieced together from bits of precious cloth. It indicates that even small pieces of textile fragments were treasured. Seated Buddha from the Mathura school in north India wears scraps of fabric sewn together. A votive frieze from Amaravati (now in Los Angeles) also depicts patchwork garment with square patches. In philosophic terms the "patchwork robe of salvation" in the Greco- Buddhist cult might be a treasured spiritual vestment or simply a skillful means of teaching (upaya).

Zen master Tongan asked, "What is the business under the patchwork robe?" Liangshan had no answer.

Tongan said, "It is wretched if you don't reach this state. You ask me and I'll tell you."

For a piece of Chinese plain silk article several pieces of gold can be exchanged with the Hsiung-nu, and thereby reduce the resources of our enemy. Thus mules, donkeys and camels cross the frontier in unbroken lines; horses, dapples and bays and prancing mounts, come into our possession. The furs of sables, marmots, foxes and badgers, colored rugs and decorated carpets fill the imperial treasury, while jade and auspicious stones, corals and crystals become national treasures.

Above all, the supply of lustrous silk to Rome by way of Parthia and Palmyra filled the coffers of the eastern kingdoms. And as planned, it also reduced the vital resources of their common enemy. The Syrian glass factories established at this time in Central Asia were probably part of the reciprocal exchange between China and Syria. By shifting important local industries from the subject nations, there appears to be a concerted effort to deny Rome the benefits of its imperial power. This ploy made Rome pay exorbitant amounts of gold to buy the luxurious silk and precious gems, cut glasses and crystals, aromatics and medicines, as well as wine from Ferghana it craved for. Pliny complained that the luxury goods were depleting the Roman treasury to the extent of fifty million sesterces annually.' A vital section of the Silk Route was owned by the Parthians and due to concerns caused by the expansionism of Rome, for about fifty years silk intended for Rome traveled through Media, Armenia and on to Colchis and the Black Sea coast. In CE 66 the ploy of crowning the Parthian ruler Trididates in Rome did not yield expected results and the Sasanians who supplanted Parthians continued to resist the advances of Rome and levied heavy taxes on the caravans passing through their territories.

The Silk Route

Roughly the size of Australia, Central Asia covers the immense expanse of the empire of the steppes called Russian and Chinese Turkistan. The overland caravan contact along the southern limits of the region became possible with the domestication of the Bactrian camel in the first centuries of the Common Era (0.2). Following camel trails nomads in the Eurasian Kazakhstan still gallop across the steppes and the high mountain pass. Ancient traditions are kept alive by the craftsmen in the vibrant markets and caravanserais of Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan and Xinjiang. It is a mysterious land of myths and legends in which the Silk Road has left behind ruined cities and tombs. The Chinese autonomous Province of Xinjiang has Takla Makan Desert and Kunlun Mountains in the south sharing borders with Tibet and Pakistan where Gilgit is located on the ranges of Karakoram. The major sites in Xinjiang are Loulan, Astana, Niya, Bezeklik, Taxkurgan and Fiaoche. In Western Kinghay, cultural counterparts of Xinjiang are Sholak Korgon, Koshoy Korgon, Shirdakbek, Lap Nor and Gandhara. Consequent to Alexander's conquest, Sogdiana between River Amu Darya and Syr Darya played an important role in the religious and cultural development of Central Asia. Until the eighteenth century, the merchants who took the hazardous journey were mostly Sogdians, a Greco-Iranian people (0.3). Thereafter the Uyghurs, a Turkic people of Central Asia, took over and established settlements along the way (0.4). Two trade routes were most traversed. One passed through the land from the hilly areas of Gilan to Alburz that came to an end at the Caspian Sea. The Hindu Kush and the Pamirs cut off Inner Asia from India and the Tibetan Plateau. The route went by way of Khurasan and Kabul and entered the Indian subcontinent. The third turned south from Samarkand and went through Bactria toward Gandhara, which is now part of Afghanistan and Pakistan. By land and sea the Silk Route linked Tamluk on the Bay of Bengal. As a thriving cult center it introduced exotic votive terracotta that glorified the goddess wrapped in splendid gold and diaphenous silk (0.5).

Far from being a monolithic entity like Egypt, China did not have nationalistic lines either in geographical or cultural terms. Chinese territory from the Yellow River to its western frontiers extended towards Afghanistan and north-eastward to the Karakoram Range and the Tian Shan Mountains, which encompass the Tarim Basin. From the Carpathians in the west, grasslands stretch north of the Black Sea across the Dnieper, Don, and Volga rivers eastward to the drainage of the Irtysh River north of Lake Balkash and on to the foothills of the Altai Mountains. The mountain barriers of Hindu Kush, Karakoram, Kuen Lun, and the Western Himalayas did not prevent the merchants and religious zealots in their activities. South of the Kazakh Steppe is the extremely arid Turkistan and its Takla Makan Desert. The far-flung region's survival centered on natural oases on the caravan routes along Samarkand (Marakanda), Bukhara, Khiva, Merv, Kokand, Kashi (Kashgar), Yarkand, and Turpan (Turfan). The Silk Route went through ancient cities in which Chang'an, Dunhuang, Kashgar, Yarkand, Khotan, Herat, and Almaty linked East and West. The relatively safe overland routes under the Mongols from the Black Sea to the Pacific Ocean were used later by the Polo Brothers.