The Trees Called Sigru (Moringa SP.)

Book Specification

| Item Code: | NAT905 |

| Author: | Jan Meulenbeld |

| Publisher: | Motilal Banarsidass Publishers Pvt. Ltd. |

| Language: | ENGLISH |

| Edition: | 2018 |

| ISBN: | 9788120842069 |

| Pages: | 162 |

| Cover: | HARDCOVER |

| Other Details | 10.00 X 6.50 inch |

| Weight | 380 gm |

Book Description

Research on the Ayurvedic materia medica, in particular its drugs of plant origin, is a venture bristling with pitfalls despite the apparent confidence displayed in the lists of botanical identifications of medicinal plants in numerous publications on the subject. This self assurance is unwarranted in quite a few cases, as this study will demonstrate.

The majority of these lists of botanical equivalents of Sanskrit plant names are not based on own research; instead, they usually reflect a consensus reached somehow among Indian Ayurvedic scholars. The course of events that resulted in this agreement remains uninvestigated. Setting aside the role of leading authorities and trend-setting publications, one of the factors involved may be the significance of a seemingly trustworthy and scientifically-looking pharmacopoeia for the Indian Ayurvedici in their competition with western medicine. In this respect the developments referred to are understandable.

From a strictly scientific point of view caution is required. When trying to take stock of the situation, one's attention is arrested by the prevalence of North-Indian influences and opinions in the secondary literature on the Indian materia medica. The concurrence mentioned is a North-Indian product that may be looked upon as an artefact since regional differences in the identifications tend to be disregarded. Though exceptions do occur, most often books by authors hailing from northern India fail to pay attention to the plants employed under the same Sanskrit names in southern India and areas such as, for instance, Gujarat and Orissa.

JAN MEULENBELD (28 May 1928 - March 26, 2017) was a physician-scholar who taught and published major works of research in Indology. Born in Borne, Overijssel, he studied medicine, and Indology under Jan Gonda, at Utrecht university. From 1954 he worked as a psychiatrist. At the end of the nineteen-sixties he returned to Indology. Immediately after receiving his doctorate in Sanskrit, Meulenbeld began to write the historical overview of the Indian medical literature. From 1978 he worked as Associate Professor of Indology at the University of Groningen and as a psychiatrist at the Van Mesdagkliniek also in Groningen. In 1986 accepted a full-time job at the Van Mesdagkliniek when the Institute of Indic Languages and Cultures of the University of Groningen was closed as part of a Dutch policy of retrenchment in the study of Asian cultures.. He worked at the Van Mesdagkliniek until his retirement in 1988.

Meulenbeld's book-length monographs include: Mahadevadeva's Hikmatprakasa : a Sanskrit treatise on Yunani medicine. Part I: text and commentary of Section I with an annotated English translation; Part II: selected passages from text and commentaries of Section II with an annotated English translation; The sitapitta group of disorders (urticaria and similar syndromes) and its development in Ayurvedic literature from early times to the present day; History of Indian Medical Literature, and Madhavanidana: English translation with principal commentaries chapters 1-10. Reprinted MLBD, Delhi, 2008

Research on the Ayurvedic materia medica, in particular its drugs of plant origin, is a venture bristling with pitfalls despite the apparent confidence displayed in the lists of botanical identifications of medicinal plants in numerous publications on the subject. This self-assurance is unwarranted in quite a few cases, as this study will demonstrate.

The majority of these lists of botanical equivalents of Sanskrit plant names are not based on own research; instead, they usually reflect a consensus reached somehow among Indian Ayurvedic scholars. The course of events that resulted in this agreement remains uninvestigated. Setting aside the role of leading authorities and trend-setting publications, one of the factors involved may be the significance of a seemingly trustworthy and scientifically-looking pharmacopoeia for the Indian Ayurvedici in their competition with western medicine. In this respect the developments referred to are understandable.

From a strictly scientific point of view caution is required. When trying to take stock of the situation, one's attention is arrested by the prevalence of North-Indian influences and opinions in the secondary literature on the Indian materia medica. The concurrence mentioned is a North-Indian product that may be looked upon as an artefact since regional differences in the identifications tend to be disregarded. Though exceptions do occur, most often books by authors hailing from northern India fail to pay attention to the plants employed under the same Sanskrit names in southern India and areas such as, for instance, Gujarat and Orissa.

Western Indologists and other scholars interested in Indian medicine run the risk of being led on a wrong track by the current state of affairs in this field, being unable to allow for disagreements in interpretation dependent on the region where a particular text derives from. An additional hurdle they have to cope with consists in deficiencies of the standard dictionaries. The botanical names they contain are obsolete and no longer valid in many instances. The sources they derive from are generally unknown. The secondary literature that has become available and new texts edited after the completion of these dictionaries present a large number of additional Sanskrit names of plants, new identifications, and new disagreements. It therefore commonly happens that the feeling arises of being lost in a jungle without a reliable guide with expert knowledge.

An easy way out is simply not to be found. An authoritative work of reference does not exist and will probably not be produced in the near future. The obstacles are many and weighty: critical editions of Sanskrit medical texts are extremely rare; the texts presuppose knowledge of the identities of the items of their materia medica; the commentators are for the most part much later than the texts and no experts in botany and related subjects. Other obstacles have to be kept in mind too: a particular name may designate more than one plant; one and the same plant usually bears a string of names; these names, not always consistent among diverse sources, do not aim at a morphological description, but mostly consist of clusters of properties and actions.

Apart from these practical complications there are more fundamental considerations making the task an arduous one. The grounds of the Indian discipline concerning plants are incompatible with those of modern botany, its taxonomy and classificatory system. The basic assumptions of Indian botany are of a disparate order. Plants which are not ritually important, useful, harmful, or ornamental, and those which have no symbolic value are, being of no interest, ignored.

The task to be discharged is therefore to unearth and reconstruct the realm of concepts of Indian thought, particularly of Indian medicine, concerning the plant kingdom, briefly a duty related to archaeology in the sense Michel Foucault' gave to it, the digging up of a lost episteme.

All the complexities of this job will become apparent in the investigation concerning the two trees to which this article is devoted.

Sanskrit texts do not describe botanical species at all since the concept of species is completely alien to their world view. Instead, plants, and certainly medicinal plants, are characterized as having a series of names, and, more importantly, a cluster of properties and actions that form a whole. This reveals an essentialist way of dealing with the world of nature, a course also apparent in nosography with its groups of prodromes and symptoms of diseases that form indissoluble wholes.

This type of thought excludes that each string of synonyms, together with the properties and actions belonging to it, necessarily corresponds to only one species of plant.

The scenery thus depicted will be illustrated and discussed in more detail with reference to the two trees called sigru and madhusigru, a subject of small importance, sufficiently interesting though as an example of how plants are dealt with in Sanskrit medical treatises and their commentaries. The data contained in a number of texts will be analyzed in succession in order to highlight their correspondences and differences.

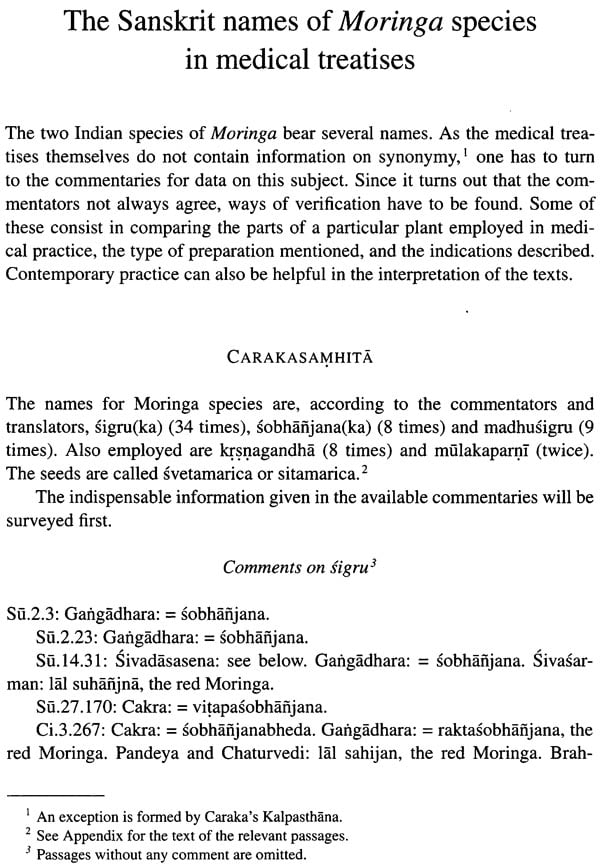

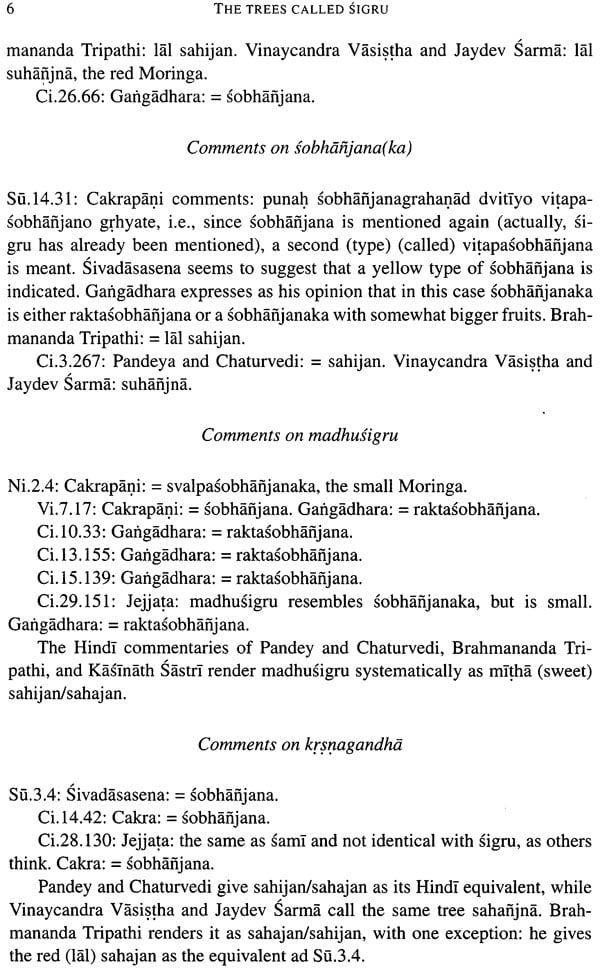

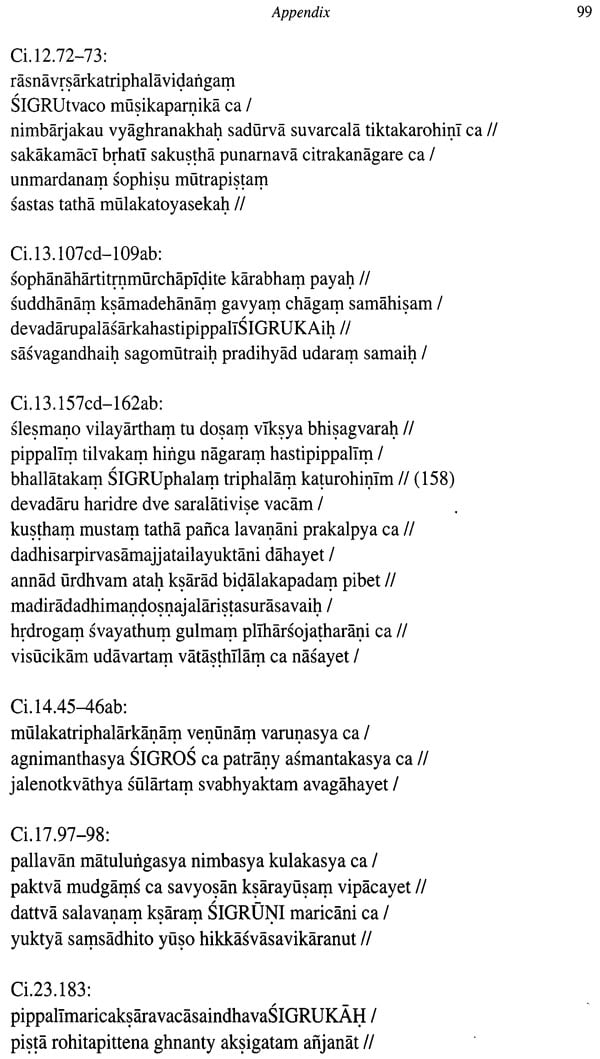

The two trees which form the subject of this study belong to the genus Moringa of the family Moringaceae,3 if we accept the consensus on this point in the secondary literature, which identifies sigru as Moringa oleifera Lam. and madhusigru as Moringa concanensis Nimmo.

Moringais a small genus of quick-growing trees. Since only two species are indigenous to India, the problem to be tackled is to examine whether or not distinctive Sanskrit names for each of them can be found in the texts and whether or not the notion that Moringa species are intended by the names sigru and madhusigru is supported by the collected data. The obstacles met with in an attempt to unravel these problems will be analysed and assigned their place in a more general perspective.

Any interpretation of the textual evidence requires acquaintance with the outward appearance of the trees and the differences between the two species occurring in India.

Moringa oleifera Lam. = Moringa pterygosperma Gaertn., called drumstick tree and horseradish tree in English, is found wild in the sub-Himalyan tract and cultivated all over India. It grows in all types of soils. Its bark is thick, soft, and deeply fissured. The leaves are tripinnate,6 sometimes 45 cm long; the leaflets are elliptic. The flowers are white and fragrant, growing in large puberulous panicles. The greenish fruits, resembling pods, are pendulous, 22.5 to 50.0 cm or more in length, usually triangular and ribbed. The seeds are trigonous with wings on angles.? These wings made Gaertner name the species pterygosperma. The seeds contain an oil, known in the trade as Ben or Behen oil, which explains the species name oleifera.

Moringa concanensis Nimmo9 has a more restricted distribution area; it is found in Rajasthan, the dry hills of Konkan, Andhra Pradesh and Coimbatore. It resembles Moringa oleifera, but its bark is more glabrous. The leaves are bi-pinnate and somewhat longer. The flowers grow in thinly pubescent panicles. Their colour is yellow, veined with red.1° The fruits are, as those of Moringa oleifera, triquetrous and the seeds are winged. The seeds contain, like those of Moringa oleifera, an oil.

The information on the size of both trees is controversial, which is unfortunate on account of the importance of this detail for an adequate interpretation of the textual evidence. The Flora of India refers to both species as large trees, Hooker's Flora characterizes Moringa oleifera as a small tree and Moringa concanensis as very similar. The Wealth of India describes Moringa oleifera as a small or medium-sized tree, about 10 m high, and Moringa concanensis as a small tree.

A not insignificant detail is that Moringa oleifera is very easily propagated not only from seed but by simply planting twigs, or even sections of large branches, in moist soil, when they will usually take root, sprout in a very short time,' and grow rapidly.

**Contents and Sample Pages**