Wisdom of Chanakya (1001 Sparks): A Book of Quotations

Book Specification

| Item Code: | NAC856 |

| Author: | V.K. Subramanian |

| Publisher: | ABHINAV PUBLICATION |

| Language: | Sanskrit Text with English Translation |

| Edition: | 2012 |

| ISBN: | 8170175321 |

| Pages: | 184 |

| Cover: | Hardcover |

| Other Details | 9.0 Inch X 6.0 Inch |

| Weight | 380 gm |

Book Description

1001 Sparks from “Wisdom of Chanakya” is the crystallized wisdom of Chanakya, also known as Kautilya, the Indian Philosopher-Statesman, who helped Chandragupta Maurya establish the first unified state In Indian History In fourth century B.C.

Often called the Indian Machiavelli, Chanakya is known for his political acumen and statecraft which enabled him to win bloodless victories over his enemies, overthrow a tyrannical regime and prevent the balkanization of India at a time when it was ravaged by foreign invasions.

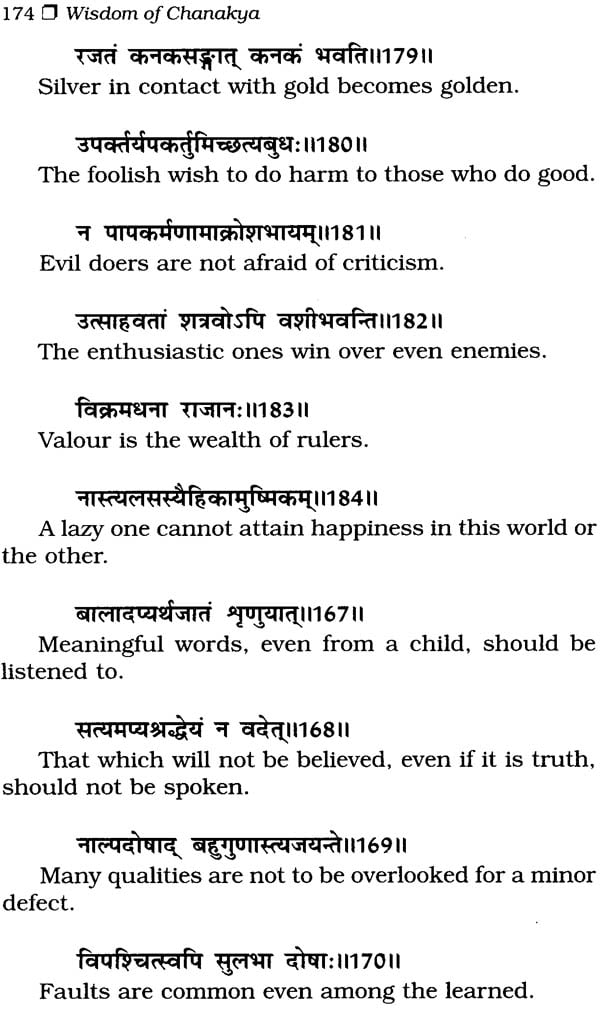

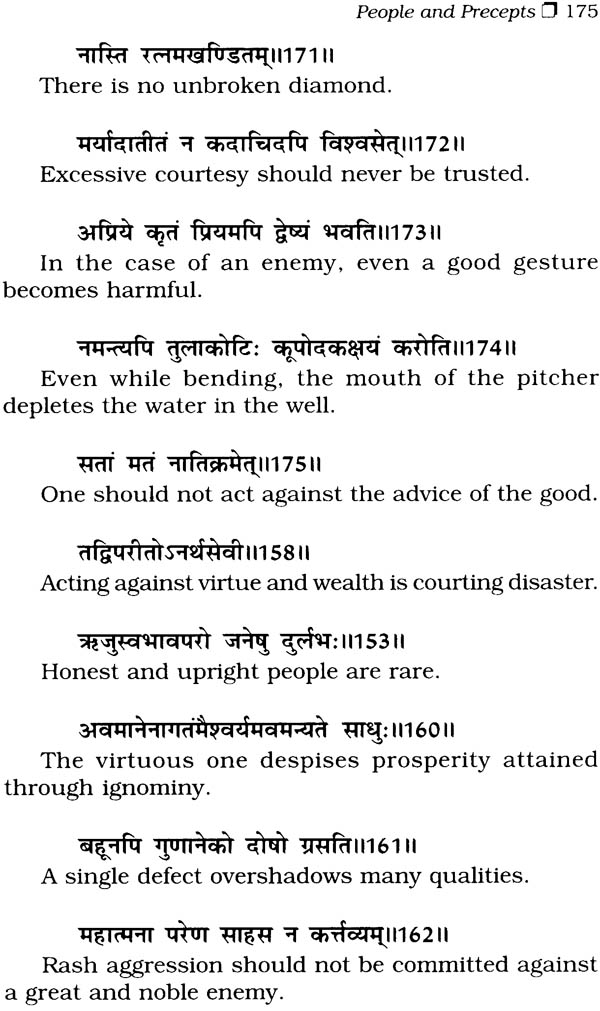

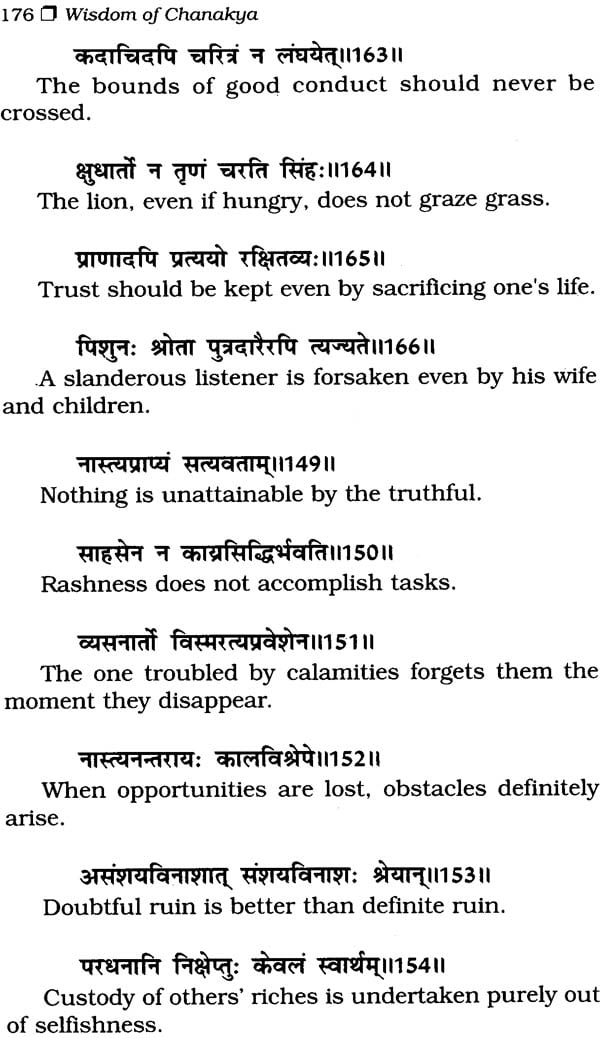

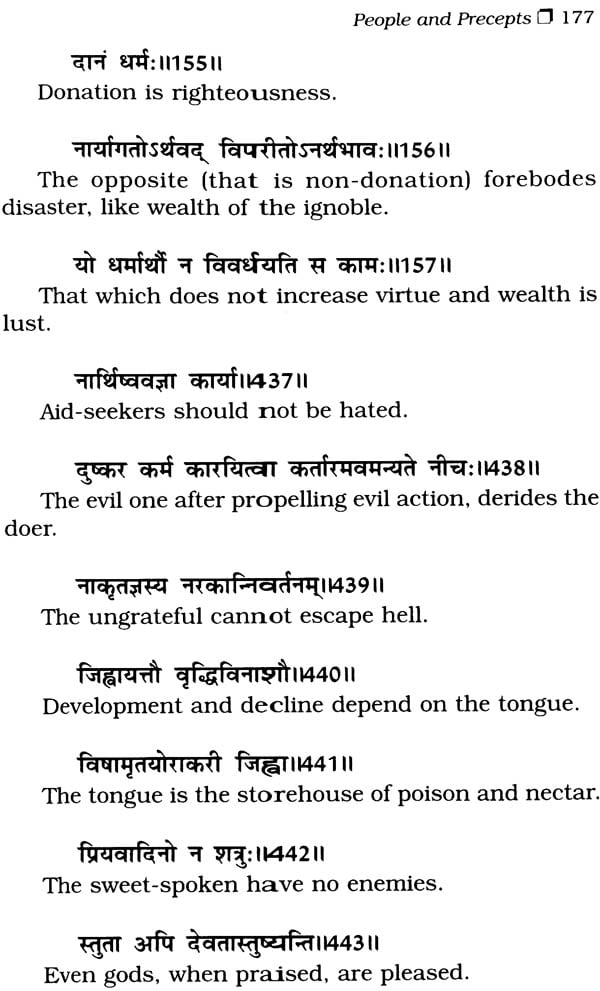

The 1001 Sparks from Wisdom of Chanakya culled from the three major works attributed to him: Arthasastra, Chanakyasutras and Chanakya-rajanitisastra (sometimes known as Chanakyan1tidarpana cover a wide range of subjects. These have been presented as: Polity and Governance, Society and Ethics, and People and Precepts.

No branch of life or learning has been left untouched by the great political genius. He has something pithy to say on politics, administration, economics, ethics, education, health, sex and self-improvement.

In terseness of expression, no language, with the possible exception of Latin, can excel Sanskrit and the great master has used this wonderful language to such perfection that one is awestruck by the volume of message often conveyed in a couple of words.

Vadakaymadom Krishna Iyer Subramanian (Birth 1930, Kerala, India) is an eminent scholar, whose life mission is to study the life and work of the great masters in the fields of Art, Literature, Science, Medicine and Biology, Exploration, Philosophy, Public Life, Social Reform, Business and Entertain-ment etc. and present them to the world.

He has already published a series of lucidly written books on the devotional mystic poet- saints of India, titled Sacred Songs of India (Ten Volumes).

An author with universalistic taste, Subramanian has over 51 books to his credit, covering a variety of subjects ranging from art to astrology and palmistry. He has been an astropalmic counsellor for the last 56 years.

Subramanian is also a reputed painter, who has held 24 one-man shows (some of them inaugurated by the President and Vice- President of India) and whose paintings (some of them in the Chandigarh Museum, India) have won wide acclaim from leading art critics of India.

The author-painter profusely illustrates most of his books.

(Chanakya: His Life, Times and Work)

Chanakya, also known as Kautilya and Vishnugupta, was the famous Indian Machiavelli who was responsible for the overthrow of the last ruler of the Nanda Dynasty and the enthronement of Chandragupta Maurya. Brahmin by caste, he roughly lived during the period 350-275B.C.

There is an interesting story about Chanakya’s first encounter with Chandragupta, which ultimately ended in their collaboration and capture of power.

One day when Chandragupta who had been dismissed from Nanda’s army was walking through the forest he saw a Brahmin pouring sugar syrup on the roots of Kusa grass. Rendered curious, Chandragupta asked Chanakya the rationale of his action, Chanakya replied: “This Kusa grass hurt my leg, I hence intend to destroy it. By pouring sugar syrup, I am rendering the root of the grass sweet. As a result, thousands of ants will be attracted to it. These ants will nibble at and destroy the root and the grass will die.”

Even as he spoke, the ants started collecting and soon there was an army of ants around the root of the Kusa grass which had hurt Chanakya. Chandragupta bowed his head before the sagacity and foresight of Chanakya and pleaded for his help and advice in becoming a Ruler. Chanakya, who already bore a grudge against Nanda, readily agreed.

Chanakya helped Chandragupta in raising a large army and defeating Nanda. After making him the Emperor of India, Chanakya functioned as his Counsellor and advised him in all matters of the State.

With the able advice of Chanakya. Chandragupta Maurya ruled for twenty-four years.

Biographical details available about Chanakya are scanty. We have mainly to rely on tradition, and the Buddhist and Jam texts of later periods.

Chanakya’s place of birth is a matter of controversy. The Mahavamsa Tika, a Ceylonese Buddhist work, mentions Taxila as his birthplace, while Hemachandra the Jam writer in his “Abhidhanachintamani” says that Chanakya, son of Chanaka, was a Dramila, that is, an inhabitant of South India.

There is another version that the name Chanakya is derived from the name of his native land (some place called Chanaka in the Punjab) as per a statement in the Jayamangala commentary on the Nitisara.

A place called “Gollavishaya” has also been mentioned as the birthplace of Chanakya in the “Parisishtaparvan”.

Kerala has also staked a claim as the homeland of Chanakya on the basis that his tuft was that of a Nambudhiri Brahmin.

Since Alexander’s campaigns were predominantly in the Punjab and Plutarch has gone on record that Alexander had met Chandragupta as a youth during his campaigns, it would be safer to accept the version that Takshasila (Taxila) in the Punjab was the native city of Chanakya, where he and Chandragupta spent several years together.

Though the story about the encounter between Chanakya and Chandragupta mentioned at the beginning of this introduction is the popular one, according to Buddhist texts and traditions, accepted by historians, the version is that Chanakya found Chandragupta in a village as the adopted son of a cowherd from whom he bought the boy by paying on the spot 1,000 Karsapanas, seeing in him the sure promise of future greatness. Chanakya is supposed to have taken the young Chandragupta with him to his native city of Takshasila (Taxila), then the most renowned seat of learning in India and had him educated there for a period of seven or eight years in the Humanities and the Practical Arts and Crafts of the time, including the Military Arts.

Despite the apparent contradictions in the various legends and traditions about Chanakya and Chandragupta as Prof. K.A. Nilakanta Sastri points out: “There is little reason to doubt the truth of the main story in Its outline: An unusually valiant Kshatriya Warrior and a Brahmin Statesman of great learning and resourcefulness joined to bring about the downfall of an avaricious dynasty of hated rulers, and establish a new empire which made the good of the people its chief concern; they freed the land from the foreign invader, and from internal tyranny, and established a State which, in due course, embraced practically the whole of India; together they organized one of the most powerful and efficient bureaucracies known to the history of the world. Kshatra (imperium) and Brahma (sacerdotium) came together and engaged in the most fruitful cooperation for the great good of the land and the people.”

Indian epigraphical researches confirm 321 B.C. as the year in which Chandragupta Maurya was enthroned as King. It would hence be safe to assume that Chanakya’s works were produced during the period 321 B.C. to 290 B.C.

The “Arthasastra”, a treatise on the science of politics, is the most famous work of Chanakya. Though it is more often known as Kautilya’s Arthasastra, the authorship of Chanakya is unmistakable.

There is a reference to Chanakya’s Arthasastra in the Panchatantra. In an introduction to his work, the author of Panchatantra refers to the Dharmasastras of Manu, the Arthasastras of Chanakya and the Kamasutras of Vatsyayana and others.

That Kautilya and Chanakya are one and the same person has been universally accepted by all historians.

The Maxims of Chanakya translated in this book are based on three works: “Chanakyasutras”, “Chanakyanitidarpana”, and “Arthasastra”.

The similarity of language and the identity of expression discernible in the first two works and the Arthasastra leaves no doubt about the common authorship.

In Dandi’s famous work “Dasakumaracharita” there is a reference to the Arthasastra of Vishnugupta. The relevant passage runs thus: “Learn now the science of politics. This has been summarized into six thousand verses for the benefit of Maurya Kings by the venerable teacher Vishnugupta. Learning this well and practising it properly, one requires the competence to deal with various tasks.”

The fact that the Arthasastra contains 6,000 verses confirms the identity of Vishnugupta and Chanakya.

That Chanakya was the Chief Minister of Chandragupta Maurya is mentioned in Megasthenes’ account of India: “Indika”. Since it is generally accepted by historians that the Greek historian came to India towards the end of the fourth century B.C., as the Ambassador of Seleucus Nicator, the Greek General of Alexander, who was defeated by Chandragupta Maurya in battle and with whom a treaty was signed ceding the territories of Kabul, Kandahar and Baluchistan to the victor, it would appear unnecessary to doubt the period in which Chanakya lived and produced his brilliant works dealing with statecraft and the various facets of public administration and private life.

Efforts have, however, been made by scholars to prove that Chanakya’s works belong not to the fourth century B.C. but to the third century A.D. It is hence considered necessary to examine the grounds on which doubts about the date of the works have been raised.

Since the period during which Chandragupta Maurya and Chanakya lived has been proved on the basis of historical evidence and epigraphical researches, the major ground open to skeptics Is to question the authorship of Chanakya and to claim that these Maxims and Aphorisms are the work of later authors erroneously attributed to Chanakya.

The intellectual genius of Chanakya was so towering and elicited so much adulation in his own time and subsequently that attempts were not infrequently made to identi1 him as the author of several works dealing with a variety of subjects ranging from sex to astronomy and mathematics.

Thus Hemachandra in his “Abhidhanachintamani” propounded the theory that Chanakya was the same Vatsyayana, the author of Kamasutra, apart from being an Astronomer, Mathematician and Logician.

The scope for such assumptions has arisen from some passages in Kamasutra which are similar to those in Arthasastra. For example, both Kamasutra and Arthasastra refer to the three divisions of Artha or Wealth: “Artho Dharmah Kama Ithyarthatrivargah” (“Riches, righteousness and love are the three aspects of wealth”).

That no aspect of learning was left untouched by Chanakya is clear from the maxims attributed to him. Thus, while his forte was politics and administration, he knew enough about ethics, morality, psychology, sex, dietetics etc. but to attribute the authorship of subsequent works like Kamasutra to Chanakya and thus create confusion about the date of his own works would be incorrect.

All knowledge and wisdom is a legacy handed over from one generation to another — through word of mouth rather than the written word in the olden days — that not infrequently subsequent authors borrowed ideas and idioms from their illustrious predecessors.

Thus merely because there are some isolated passages in Kamasutra reminiscent of verses in Arthasastra, it would be indefensible to argue that since the date of Kamasutra is being taken as the fourth century A.D., Chanakya’s works could not belong to a much earlier period.

Similar is the case with reference to the mention of Chanakya’s works in Kamandaka’s “Nitisara”, a work believed to have been transported into the island of Bali by Indian immigrants in fourth century A.D. Efforts have also been made, on the basis of certain passages in Kalidasa’s works, to prove that Kalidasa and Chanakya belonged to the same period. Some have even gone to the extent of claiming that the two were one and the same person.

It is true that the indebtedness of Kalidasa to Chanakya is proved beyond doubt by the fact that Kalidasa’s “Raghuvamsa” contains many words which are used in a technical sense in the Arthasastra. Examples are: Sastra, Danda, Dandaniti, Prakriti, Mantra, Saptanga, Kosa Mandala etc.

Dr. Raghavan, the eminent Sanskrit scholar of the Madras University in his paper on “Kalidasa and Kautilya” (read before the thirteenth session of the All India Oriental Conference held at the Nagpur University in 1946), has cited a number of instances of parallel ideas in the works of the two and remarks: “All these presuppose that Kalidasa had before him some texts on Polity in which there was a large mass of technical terms whose meanings were well defined and which had, therefore, come to be well understood.”

By a detailed analysis. Dr. Raghavan has proved that the most important of the texts on Polity which Kalidasa had with him was the Arthasastra of Chanakya.

This only indicates that Chanakya lived many years before Kalidasa and there is no evidence to dispute Chanakya’s contemporaneity with Chandragupta Maurya, whose enthronement in 321 B.C. is generally accepted by historians.

Chanakya functioned as the Chief Minister of Chandragupta Maurya between 323 and 298 B.C. and it would not be unreasonable to assume that Chanakya composed his great works after retiring from active politics, that is, after he successfully consolidated the Maurya empire and made his rival Rakshasa the Chief Minister of Chandragupta Maurya. On this basis, Chanakya’s works belong to the third century B.C.

Since conclusive evidence exists to show that Chanakya’s works could not be later than third century AD., disputes about the date of Chanakya’s works get narrowed down to a period of six centuries. We may leave researchers and scholars to sift evidence and come to some firm conclusion, if and when they desire.

As far as we, on the threshold of twenty-first century, are concerned, we may derive satisfaction that we have been bequeathed works of wisdom, which are nearly two thousand years old, and we may attempt to learn how much of these are relevant to modern times and can be used with advantage by those who shape a country’s destiny or an individual’s future.

In this light, all arguments concerning the date of Chanakya’s works or whether he was born in South India assume less importance than a critical study of the texts which are available to us and which after editing by various scholars are broadly attributed to him. Before we attempt to study these works, we may try to make an assessment of Chanakya, the man, who played a dominating part in the establishment, growth and preservation of the Maurya empire.

| Introduction | 11 | |

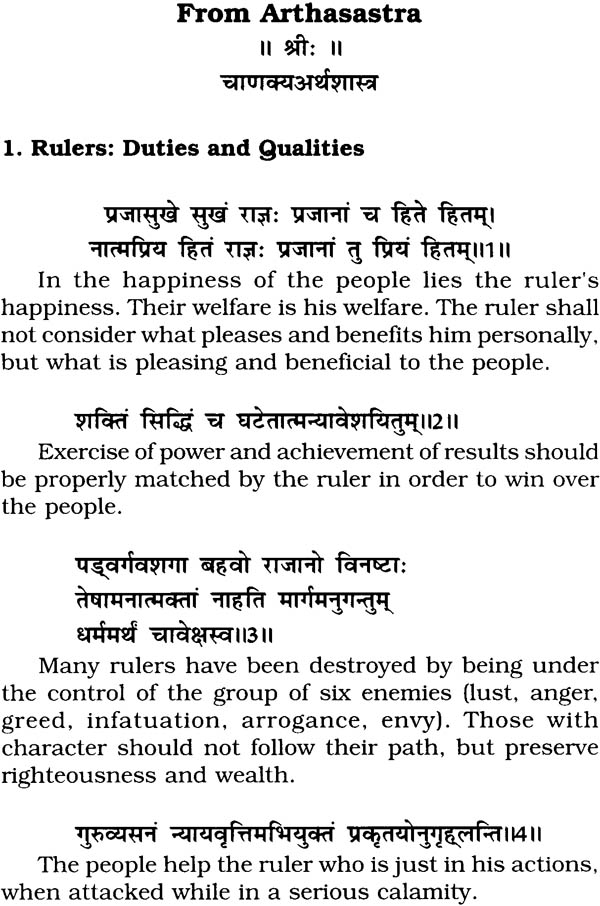

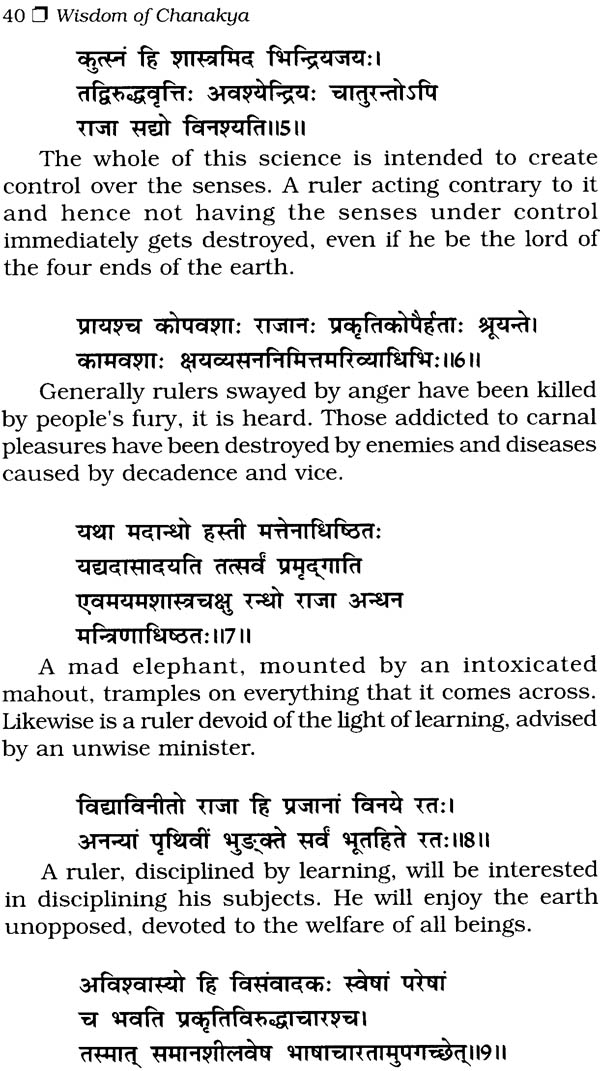

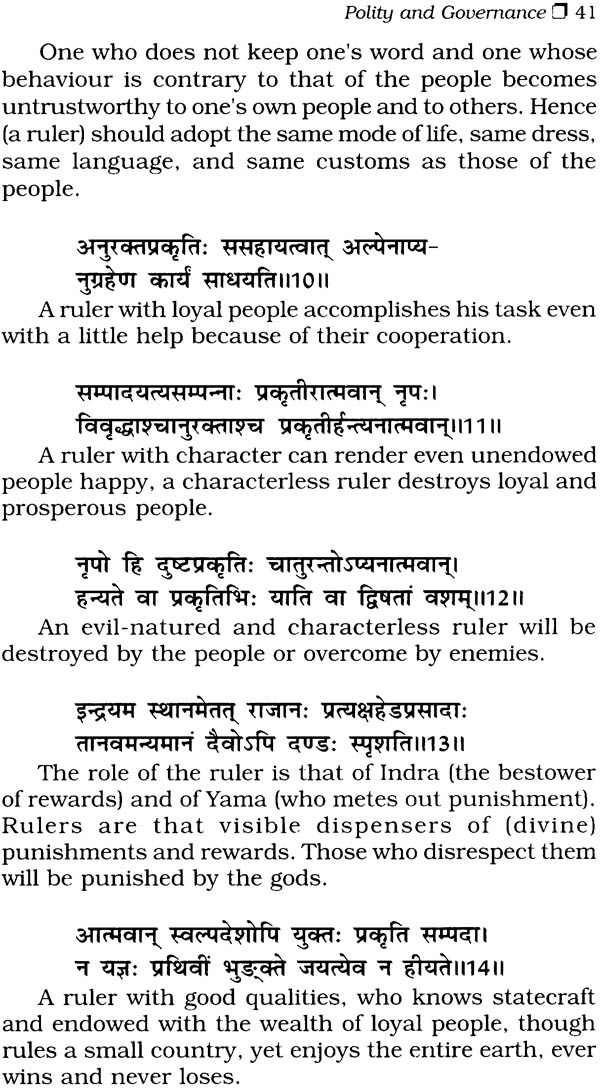

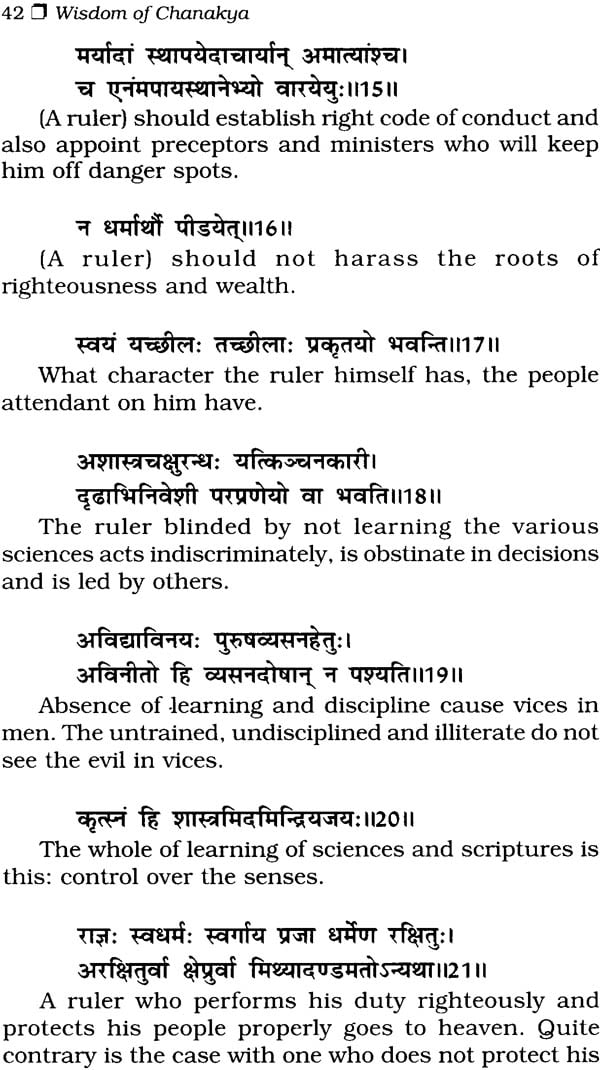

| 1. | Polity and Governance | 37 |

| 2. | Society and Ethics | 109 |

| 3. | People and Precepts | 141 |

| Bibliography | 185 |