Dhammapadapali and Suttanipata (Pali Text With English Translation)

Book Specification

| Item Code: | NAR925 |

| Author: | Dr. O. P. Pathak |

| Publisher: | Bharatiya Vidya Prakashan |

| Language: | Pali Text With English Translation |

| Edition: | 2004 |

| ISBN: | 8121701724 |

| Pages: | 463 |

| Cover: | HARDCOVER |

| Other Details | 9.00 X 6.00 inch |

| Weight | 850 gm |

Book Description

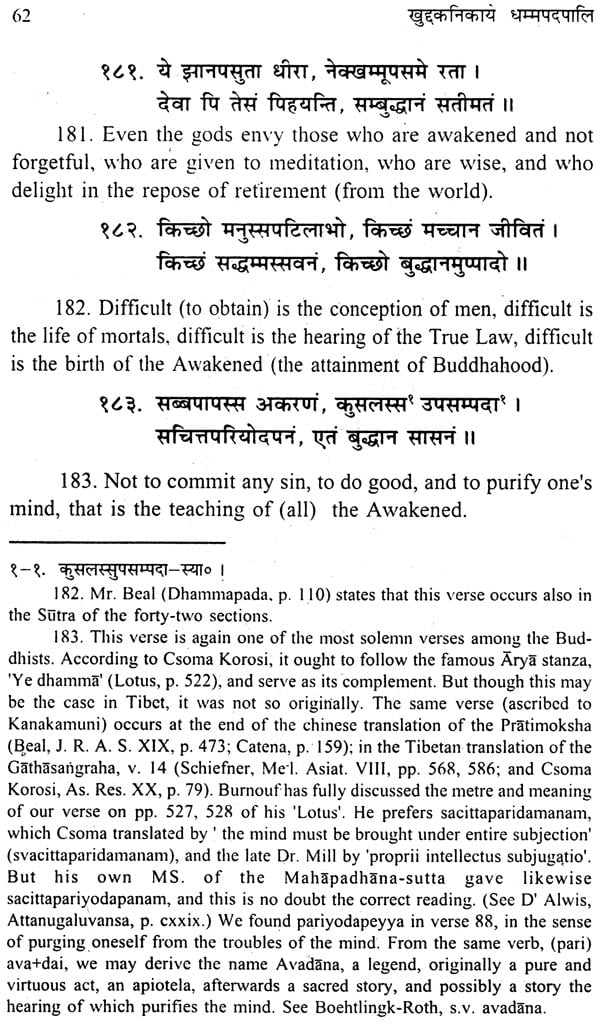

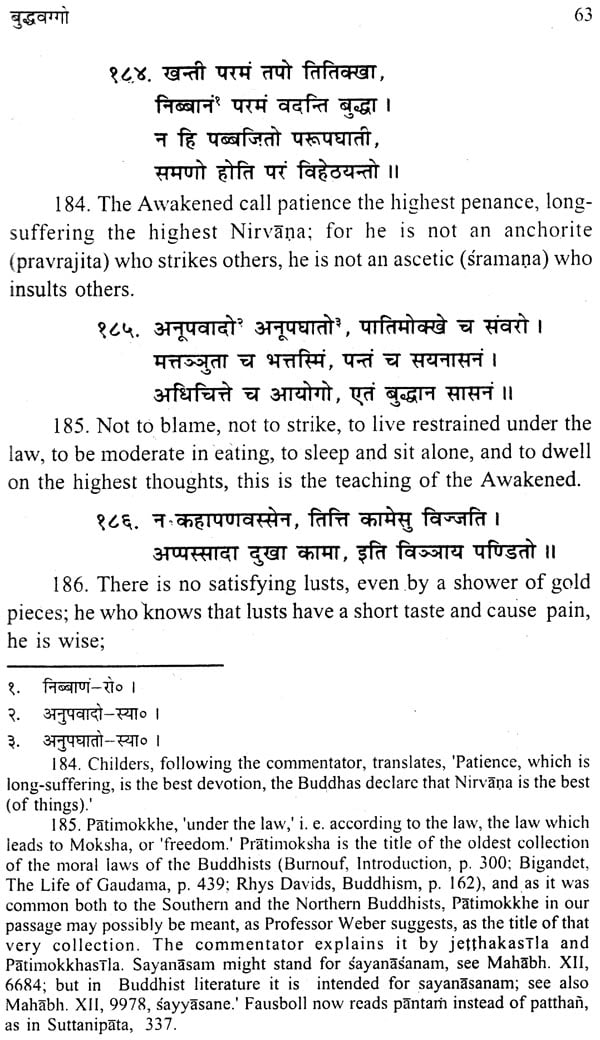

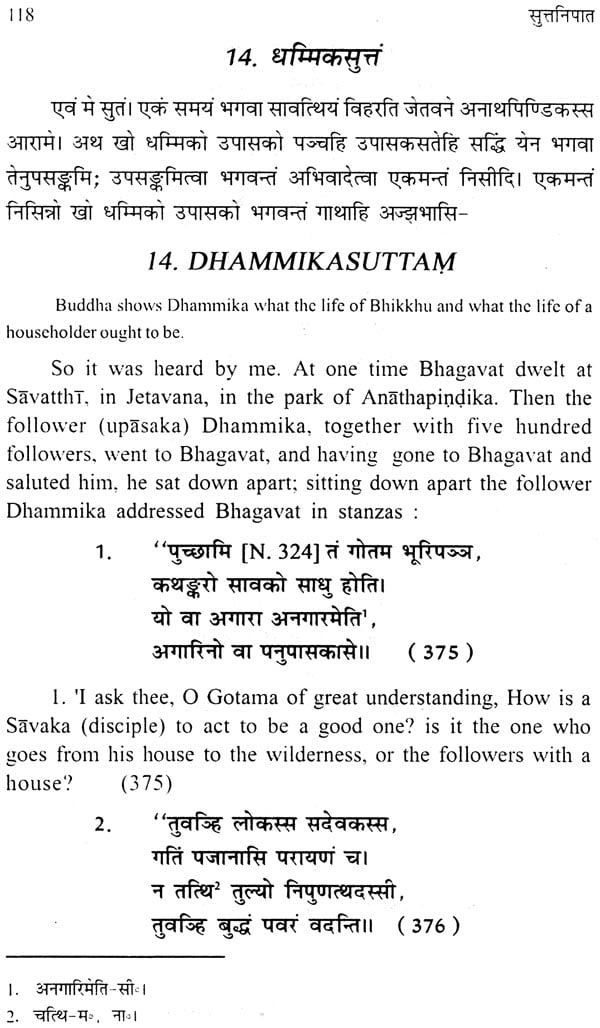

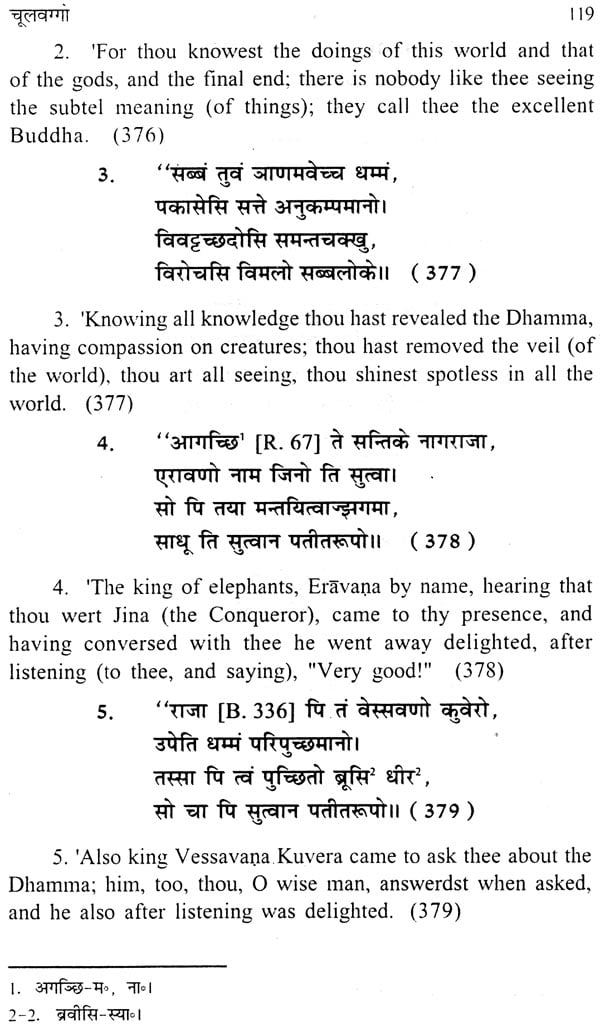

The Dhammapada is the second book of the khuddakanikaya which belongs to the sutta-pitaka of the Tipi-taka. There are 423 verses in Dhammapada which are divided into twenty six chapters. In this book we can hear the voice of the Buddha. It is one of the well-known works both in literary and ethical aspects. Running into verses with short, clear and convincing explanations, symbolizing with easily understandable similies, each verse of the book is pregnant with great significance which directly penetrates to heart of listeners.

In this book, the message of the Buddha is a message of joy. He found a treasure and he wants us to follow the path that leads to this treasure. He tells man that he is in darkness, but he also tells that there is a path that leads to light. He wants man to arise from a life of dreams into a higher life where man loves and does not hate, where man helps and does not hurt. His appeal is universal, because he appeals to reason and to the universality in us: "It is you who must make the effort. The great of the past only show the way." He achieves a supreme harmony of vision and wisdom by placing spiritual truth on the crucial test of experience; and only experience can satisfy the mind of modern man. He wants to us to watch and be awake and he wants us to seek and to find.

The word Dhammapada has two component parts: "Dhamma" and "Pada". "Dhamma" means pure dhamma and "Pada" means path. So "Dhammapada" means 'the path of pure Dhamma.' "Dhamma" may also be interpreted as `Dharma, "religion', 'virtue'. It is used in many different sense in the different schools of religious traditions of Indian thought.

"Dharma" which may be compared to the earlier term, `rta' and is derived from the root `dhr,' literally means 'what supports or upholds' as the Mahahharata puts it. The word "dharma" comes from 'upholding' and human beings are held together by "Dharma." It is 'the final governing moral principle or ethical law of the universe'.

We have four stages in the development of the concept of Dhamma in Indian thought':

1. "Dhamma" as the duty of following the Vedic injunctions.

2. "Dhamma" as moral virtues of non-injury, truthfulness, self-control etc.

3. "Dhamma" as self-knowledge through yoga.

4. "Dhamma" consists in the worship of god without any ulterior motive, a worship performed with perfect sincerity of heart by men who are kindly disposed towards all, and who have freed themselves from all feeling of jealousy.

The word "pada" means foot, step. Here, it means a word, verse, stanza, line and sentence. "Pada" implies section, portions, parts or way. The Dhammapada is a collections of those edifying verses of Buddha which go a long way in making one's life ethically sublime and morally rich and meaningful inasmuch as they elucidate universal laws like "enmity cannot be ended by "enmity, it can be ended only by loving kindness (Metta)" as also the Dhammas to be practised for leading a pure life.

The "Dhammapada" has a very important place in Pali Literature. As it is in verse and as it is couched in simple, felicitous and perspicacious language, it is easy to remember; as its theme is ethical, it is very inspiring, and as it sets forth the true Dhamma, it is ennobling.

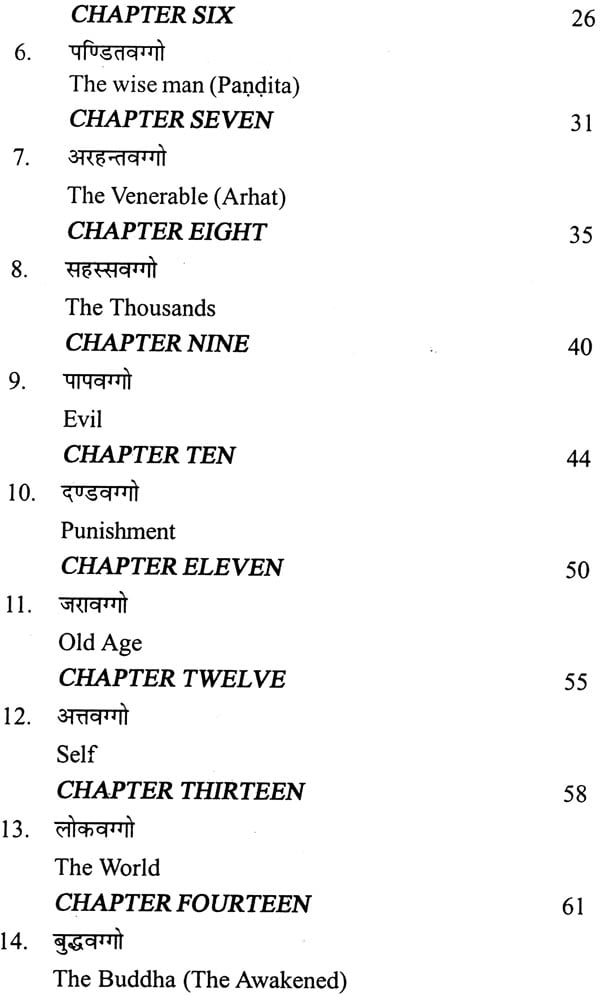

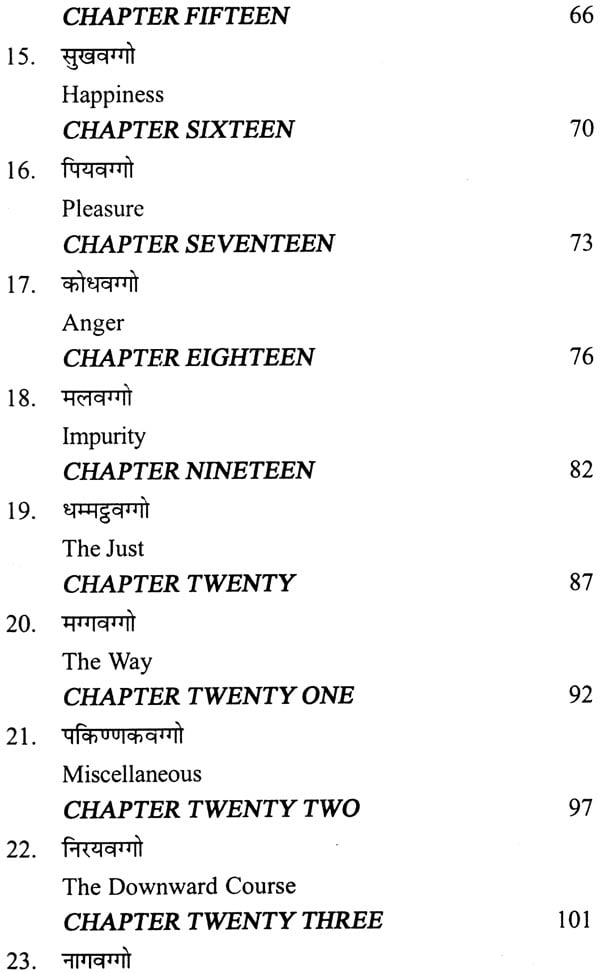

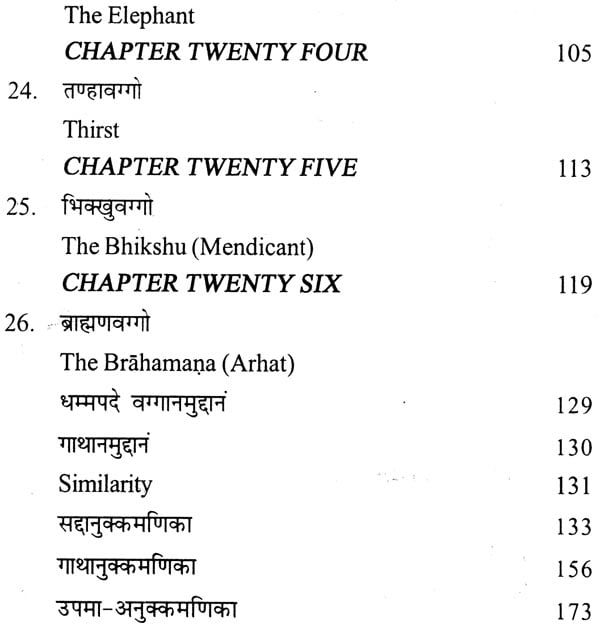

"Dhammapada" is composed of 423 verse which are divide into twenty six vaggas. The first vagga is Yamakavagga and last one is Brahamanavagga. There are three hundred five stories under 423 verses. Herein below English renderings of some of the Gathas is given.

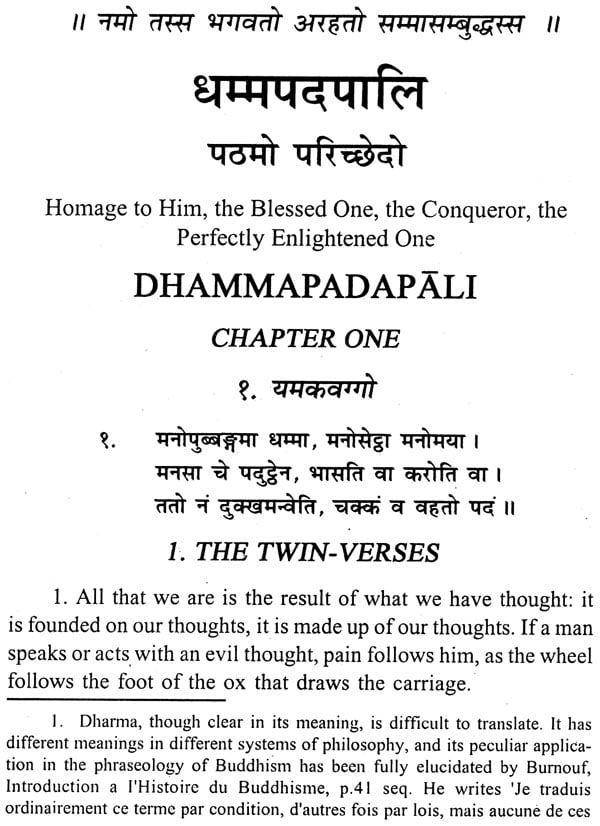

All evil states emanate from mind. Therefore mind is called the source of all evil actions. It one speaks with a wicked mind or acts with such a mind he is bound to suffer. Suffering follows him in the same manner as a wheel of bullock cart follows the hoof of the ox. And if one speaks or acts with pure mind, happiness follows him in the same way as one's shadow follows one. Hatred does not cease by hatred. It ceases by love. (Yamaka-vagga).

Vigilance is the path to the deathless and heedlessness is the path to death. The vigilant and watchful never die but those who are not so are ever like the dead. The wise people, meditative, steady, always possessed of strong powers attain to Nirvana, the highest happiness. (Appamada-vagga)

An enemy cannot do so much harm to an enemy or a hater to a hater, as an ill-controlled mind can do to one. In fact, it can do greater harm than an enemy. But, a well-controlled mind does more good to one than done to him by his parents and other relatives. (Citta-vagga).

Just as these are some flowers which though lovely and beautiful to look at, do not have any fragrance so fruitless are the well-spoken words of one who does not practice them. In contrast to this the well- spoken words of one who practises them are as fruitful as flowers which are lovely, beautiful and full of fragrance. (Puppha-vagga)

It has been a great and unexpected pleasure to me to have to bring out a new, the third edition of my translation of the Dhammapada. The first was published in 1870, the second in 1881. I cannot indeed pretend to have improved the present edition very much, for I have not had any time left during the last few years to continue my study of Pali, Nor has Pali ever been more than a parergon to me. I began it is 1845 during my stay at Paris with Burnouf, who was then almost the only scholar who could read Pali texts, and I still have a letter of his in which he apologises for his imperfect knowledge of the language. At that time Pali scholarship had not yet become a special and independent study, but it was a kind of annexe to Sanskrit. Men like Bopp and Burnouf were expected to teach not only Sanskrit and Comparative philology, but at the same time, Zend, the Prakrit dialects, and, as one of them, Pali. Clough's Pali Grammar (Colombo, 1824 and 1832) and Tumour's Mahavamso (1837) were all that we had to depend on. Some advance was made by Spiegel and Westergaard, but the real impulse to an independent and scholar like study of Pali literature came from my friend childers, the author of the first Pali Dictionary, published in 1875. Before that time the only names to be mentioned in Pali scholarship were those of James D'Alwis, Spence Hardy, Spiegel, E. Kuhan, Minayeff, Senart, Weber, and last, not least, Fausboll. After the publication of Childers' Dictionary, the progress of Pali Scholarship has been very rapid, and the number of Pali texts translations has increased very considerably. As the most ac-tive among the new generation of Pali scholars deserve to be mentioned Rhys Davids, the founder of the Pali Text Society, Oldenberg, the editor of the Vinaya-pitaka, Trenckner, E. Senart, Feer, Morris and the translators of the Jataka, Professor E. B. Cowell, Messrs, R. Chalmers, W. H. D. Rouse, H. T. Francis, and R. H. Neil.

The most favourite Pali text seems to have been the Dhammapada. It is certainly a most interesting collection of verses, giving a trustworthy picture of Buddhist thought, particularly in its practical and moral character. Consisting of short sentences it seems at first an easy book to translate, but the very fact that these 'versus memoriales' stand by themselves without any context to throw light on them creates a peculiar difficulty, much the same as that with which the readers of another elementary book, the Hitopadega, are well acquainted. Like the Hitopadega, the Dhammapada also may be called an easy and at the same time a very difficult book. The verses being often torn from the context to which they originally belonged, may indeed be rendered word by word, but they leave us often in the dark, particularly where two readings are possible, which of the two we ought to choose; while if we knew what preceded and followed them in their original con-text, we should find our choice much easier. Though many difficult and obscure passages in the Dhammapada have now by a succession of translators and commentators been elucidated, many more still remain which require renewed study. It may seem strange to outsiders that there should still be so much uncertainty as to the exact meaning of many Pali words. The meaning of the very title of our book, the Dhammapada, is still contested. I have produced whatever arguments I could collect in support of the meaning of 'Path of Virtue' or 'Path of the Law.' But I am far from saying that the translation 'Collection of Texts of the Law,' Worte der Wahrheit,' is impossible. What we want to settle the point is some ancient Buddhist authority to tell us with what intention this title was originally given. For titles are often fanciful, and mere scholarship is not sufficient to enable us to speak with magisterial assurance.

Let us take another instance. One of the commonest words in Buddhist philosophy is sankharo. It corresponds to Sanskrit Samskara. The meanings of the Sanskrit word are difficult enough. It means the forming of matter, it can mean refining, polishing, embellishing, also the preparing of food and the moulding of clay. Purifying rites also are called samskara and the impressions of the mind as well as the result of them, the dispositions, tastes, talents or inclinations, may go by the same name. In Pali, however, the growth of the meanings of sankharo becomes far more complicated. It means there also preparing, but the Buddhist, as if remembering that samskara meant etymologically putting together, and then what has been put together, uses sankharo in the sense of anything that has been made and will therefore perish. According to Hindu philosophy whatever has been put together or made can be put asunder or unmade, and thus sankharo came to be used not only for what we should call the created or material world, but for anything in it that is anitya or perishable. Thus sankharo may sometimes be rendered by matter in general, though chiefly by organised or living matter, except that sankharo includes what we should call attributes also. Lastly, like saniskaro may mean the impressions left on the mind, and the resulting states of the mind predispositions, talents or character, in which sense it is often used by the Sankhya philosophers. If then we read verse 368 that the quiet place of Nirvana is sankharupasamam sukham or happiness arising from the quieting of the sankharas, we may translate either 'from the cessation of all existing things,' or' from the calming of all desires or affections. 'Hence Fausbnll translates 'naturarum redatio;' Weben, 'wo aufhoren die Einkleidungen; 'Gray, 'life-ending;' Hu, 'oil cessent les exist-ences;' V. Schroeder, 'wo alles Ding zur Ruhe kommt,' whereas I prefer to take upasama in the sense of calming, and sankharo in the sense of all states of the mind, more particularly the calming of all desires and affections.

**Contents and Sample Pages**