Srimad Bhagavata : The Book of Divine Love (Sanskrit Text with Transliteration and English Translation)

Book Specification

| Item Code: | NAG843 |

| Author: | Swami Gitananda |

| Publisher: | ADVAITA ASHRAM KOLKATA |

| Language: | Sanskrit Text with Transliteration and English Translation |

| Edition: | 2019 |

| ISBN: | 9788175054189 |

| Pages: | 624 (18 Color Illustrations) |

| Cover: | Hardcover |

| Other Details | 9.5 inch X 6.5 inch |

| Weight | 1.40 kg |

Book Description

About the Book

For a long time human beings remain forgetful of God and spend their time in worldly enjoyments. Through that, however, none can realise God. But when one realises one’s mistake, one finds out the way to the attainment of God, and at that time the truly auspicious moment of life comes and presents itself.

Though Shukadeva narrated Srimad Bhagavata for the sake of Parikshit, it is a treasure belonging to each and every human being. There is no record of the number of persons who have read this great work and attained peace and blessedness. Whoever listens to the Bhagavata and sings God’s glories, become blessed, overcomes the fear of death, and becomes immortal.

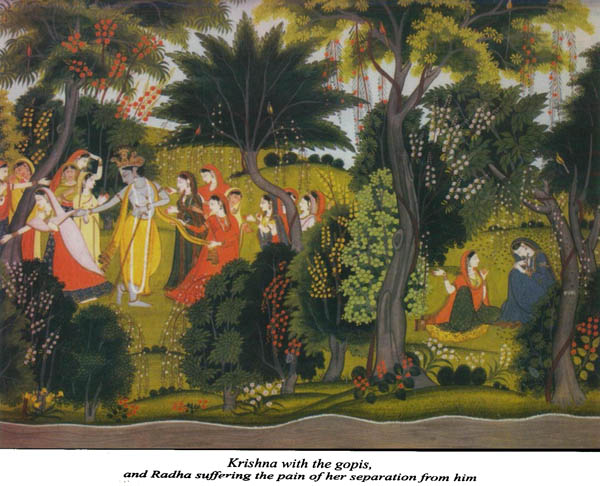

In the course of conversation, one day Sri Ramakrishna had remarked: “Whether you accept Radha and Krishna, or not, please do accept their attraction for each other. Try to create that same yearning in your heart for God. Yearning is all you need in order to realise him.” The kind of intense attraction that Radha had for Krishna, which is described in the Bhagavata, make that attraction the ideal of your life. The point is we have to love God, have to taste the sweetness of God.

Regarding the love of the gopis for Krishna, Swami Vivekananda says: “Ay, forget first the love for gold, and name and fame, for this little trumpery world of ours. Then, only then, you will understand the love of the gopis, too holy to be attempted without giving up everything, too scared to be understood until the soul has become perfectly pure. People with ideas of sex, and of money, and of fame, bubbling up every minute in the heart, daring to criticise and understand the love of the gopis! That is the very essence of the Krishna incarnation. Even the Gita, the great philosophy itself, does not compare with that madness, for in the Gita the disciple is taught slowly how to walk towards the goal, but here is the madness of enjoyment, the drunkenness of love, where disciples and teacher and teachings and books and all these things have become one: even the ideas of fear, and God, and heaven everything has been thrown away. What remains is the madness of love. It is forgetfulness of everything, and the lover sees nothing in the world except that Krishna and Krishna alone, when the face of every being becomes a Krishna, when his own face looks like Krishna, when his own soul has become tinged with the Krishna colour.”

Preface

Since ancient times, Srimad Bhagavata holds a central place in the spiritual horizon of India. In this age, where human life is hectic, people have hardly any free time. Nevertheless, even in the midst of their busy life, many want to know about Bhagavata, which is the gist of Vedanta. But to read or listen to Bhagavata in Sanskrit, which is a long text containing around eighteen-thousand verses, is beyond many. Further, though this crown-jewel of the Puranas has been translated into many languages, to read the huge book in translation is also difficult for the ordinary folks.

In the present book, in thirty-six chapters we have briefly discussed only the important topics of the original Bhagavata. As a result, some of the stories, characters, and philosophical ideas from the original are not to be found here. But after reading this book, those readers in whom the desire to further taste the joy of reading Bhagavata increases, we hope they would take up the study of this work in detail and derive joy.

The Sanskrit text of Bhagavata is very touching. We have presented the verses in Sanskrit, along with their translation, for the benefit of those who know the language at least to some extent; and those who do not know the language will also be able to enjoy the sweetness of the work by reading the translation.

After the great sage Vyasa wrote the Brahma Sutras, the Mahabharata, the seventeen Puranas and other works, instructed by Narada he compiled the Bhagavata. Therefore it is clear that, in this immortal work which Vyasa presented to the world as Bhagavata Dharma, he has brought together all the great experiences of his life and the gist of all his works, and has wonderfully presented the harmony of the spiritual paths of knowledge, action, devotion, and yoga. It is the same non-dual reality, Brahman, which is attributeless, formless, and transcendent to mind and speech, which assumes a divine form with attributes and incarnates in this world in every age. Thus it blesses the world and the devotees with ultimate well-being and joy-this is the great proclamation made by the Bhagavata. Many compare Bhagavata to an extremely delicious sweet that has been fried in the clarified butter of knowledge and steeped in the honey of love. Therefore it is said: “Continuously quaff this nectar in the form of Bhagavata.”

In the original Bhagavata, which chiefly concentrates on the glories of Sri Krishna’s qualities and divine sports, the name “Krishna” has been mentioned countless number of times in different contexts. In this book we have sometimes referred to “Krishna” with “Sri” and sometimes without it. There were some, like the residents of Vraja, Jarasandha, Shishupala and others, who knew about Krishna’s divine glory to some extent; even then they considered him to be a human being like them. While referring to Krishna in their context, we have used the word Krishna without “Sri”. Wherever he is looked upon as God or the Supreme Self, and is accordingly dealt with, in such contexts the word “Sri” has been used. Apart from this, at some places where he is looked upon as a mixture of the human and the divine, he has been referred to with “Sri” as well as without it.

The publication of this book has been made possible by the unstinted help and encouragement of Swami Lokeswarananda. I offer my reverential obeisance to him. My due salutation and regards, as the case may be, to revered Swami Atmasthananda, Sri Nirod Baran Chakraborty (the former head of the department of philosophy, Presidency College), Swami Smaranananda, Swami Prameyananda, Swami Jushtananda, Swami Tattwavidananda and others. By helping me in various ways in the publication of this book, they have left me indebted. The well-known scholar, Sri Govindagopal Mukhopadhyaya, has written a foreword to this book and has enhanced its worth. I convey my respectful regards to him. Even apart from these, many others have helped in bringing out this book. I convey by heartfelt gratitude to each one of them.

In this life it is not possible to get a human companion fully to our liking. That’s why man feels lonely. When we are young and when our body is strong and active, we pass our time in various activities and fun and frolic. But owing to aging, when the body becomes inactive, then those things do not taste good anymore. Then the soul longs to get someone, longs to be lost in the thought of someone who is completely one’s own; but where to find such a one who is completely one’s own? In the Bhagavata, which is the essence of the Indian spiritual lore, it is stated that the thought of God removes the sorrows and sufferings of this world, and that listening and thinking about God make us feel good. This is the hopeful message of the Bhagavata which needs to be verified in each one’s life. This book gives everyone that opportunity, and with the hope that it would help everyone remove their sense of loneliness, we present this book.

Foreward

Srimad Bhagavata is an infinite ocean of supreme nectar; and He (God) Himself is that nectar, whose indication we find in the declaration of the Upanishads: “One who attains that nectar becomes one with bliss.”

That’s why Bhagavata summons us and tells: “Come, quaff this nectar in the form of Bhagavata till the end.” But in the present times, the persons from whose mouth people used to listen to the nectarine words of Bhagavata are no more to be found. Also the Sanskrit language has disappeared or, we may say, has been exiled, knowing which people could by themselves read and savour the sweetness of Bhagavata and become blessed. Today that door too is closed for most of us.

At such an hour, when civilization and culture are at the crossroads and facing threats, Sri Ramakrishna himself has as if inspired Swami Gitananda to churn the sweet ocean of Bhagavata and present to us its nectarine essence in a language that will be easily comprehensible to all. Just as he has chosen the brilliant Sanskrit verses from the original to make people get a taste of the original, he has also translated them in fluent and elegant Bengali so that everyone can easily taste the sweetness of Bhagavata in its original. For one more reason this book is wonderful, and that is: Sri Krishna is the central character of Bhagavata, and the author has included almost all his divine sports, from his birth till the end. Along with this, other important portions like the dialogue between the nine sages and King Nimi, which are pathfinders to humanity, have also been included. In short, in this wonderful work he has churned out the gist of Bhagavata. The language is clear and easy all through, and the absorbing nature of the stories takes us from one chapter to the other by themselves. Wherever he could, the author has brought in the comments of the famous Vaishnava teachers so that the readers may benefit from the loveliness of those commentaries. Over and above all this, what attracts everyone’s attention is the way living instances from the great lives of Sri Ramakrishna, Holy Mother and Swami Vivekananda have been introduced from time to time to clarify and enlighten us about the ideas of Bhagavata. If this had been done in a still more elaborate way, this great work would have been far more enjoyable. After having made us have a little taste of this, the author stopped, as it were, leaving us with a desire for more.

Sri Ramakrishna has instructed that for this Kali Yuga, bhakti according to Narada is the only way. He has also clearly pointed towards devotion, the devotee, and the Bhagavata (bhakti-bhakta-bhagavata) as the supreme refuge. By bringing out this wonderful version of Bhagavata, which can be easily followed by all, Swami Gitananda has given, as it were, a concrete form to Sri Ramakrishna’s divine statement. Everyone who thirsts for the nectar of Bhagavata will remain indebted to him because, through this great work all will be able to drink nectar at all times.

Srimad Bhagavata doesn’t need a foreword or introduction. It is self- revealing. But it is the very nature of monks to make unworthy persons worthy, and to infuse purity into them by making them associate with Bhagavata. That’s why it was impossible for me to say no to his entreaties. Though being fully conscious of my own ineptitude and ineligibility, I associated myself with the story of Krishna because I have at least understood this much (Srimad Bhagavata, 12.12.49-50):

“Works that reveal the glory of God manifesting through all life and nature promote what is true, what is good, and what is holy. It is that literature which sparkles with the excellences of the Divine that remains ever novel in its power to delight and charm the mind. It alone can sustain the mind always as in a festive mood, and dry up the ocean of samsara in which man is plunged.” Therefore I too follow revered Swami Gitananda in singing the glories of God, and hope that every reader also will join and become blessed by tasting the bliss of Bhagavata. I not only wish but also pray for the immense popularity of this great book. This is a great book, not only because of the greatness of its content but also because of the greatness of the mood and sweetness it generates. There’s little doubt that readers will realise this truth.

Introduction

In the Vedic age, in the samhita portion of the Vedas, hymns were sung in praise of gods like Indra, Mitra, Varuna, and others. However, there is a point to be noted in this regard: there was then the clear notion that these gods are the manifestations of one reality. Truth is One; sages address it by different names, says the Rig Veda. Following the samhita portion, in the brahmana portion the way to the performance of ritualistic actions, like sacrificial rites, were stipulated. This brahmana literature is called the karma-kanda of the Vedas. But later, amongst the followers of karma-kanda, there arose some who realised that such actions cannot bestow on us infinite happiness, immortality, and everlasting peace-that these are not capable of releasing human beings from the clutches of birth and death. The Katha Upanishad says (1.2.10): “I know that this treasure (actions done for attaining objects of enjoyment) is impermanent-for that Permanent Entity (atman) cannot be attained through impermanent things.”

There is a limit to worldly enjoyments; they are not infinite. The atman, which is infinite, can never be attained through something finite like performance of sacrifices. Thinking thus, some began to follow the science of Self-realisation as given in the Upanishads, which is known as the path of knowledge (jnana-marga). There were still others who failed to fully understand and accept the Non-dual Truth as the Supreme Reality. They developed faith in the path of devotion (bhakti-miirga). Their dependence was on an infinitely powerful God, who had also limitless qualities and limitless compassion. Though in the Vedas there are hymns to gods like Indra, Varuna, Agni, and others, wherein we find the seeds of devotion (bhakti), some people feel that it is the Ultimate Reality of the Vedas that has been imagined as these deities.

Anyway, along with the practice of singing hymns to gods, which is found in the samhita portion of the Vedas, the practice of performing sacrifices as laid down in the brahmana portion, as well as the practice of Self-enquiry as given in the Upanishads, there came into being, almost simultaneously, another practice-the practice of devotion (bhakti). According to one’s eligibility and taste, the spiritual aspirants of India chose a particular spiritual path and discipline. In this way they attempted to arrive at a harmonious view of unity. And we should remember that these three streams of spiritual disciplines prevailed in India centuries before the birth of Christ.

It is known by hearsay that after writing the Brahma Sutras, the epic Mahabharata, and the Puranas, the great sage Vyasa realised that in and through his life-long writings he had not been able to express any extraordinary spiritual ideology, or present a role model, depending on which, age after age, human beings could make their lives blessed. Owing to this he became extremely sad and immersed himself in meditation on the Supreme Brahman. It was during this meditation that the idea of Bhagavata flashed in the depth of his heart. Thus, Bhagavata was obtained in deep meditation. Its subject is also, therefore, an object of meditation, and it is only in deep meditation that one realises the Truth presented there. In this way, Bhagavata is best understood in meditation.

You may ask: It is said that even after composing such great works like the Brahma Sutras, Mahabharata and the Puranas, Vyasa suffered from sorrow. Is this an imagination of the author in order to eulogise Bhagavata or is there any truth in this statement?

It is seen that until the seventh century, Buddhism was extremely powerful in India. Then Shankaracharya came and, owing to his brilliant intellect and extraordinary comprehension and interpretation of the scriptures, practically eliminated Buddhism from the land. The philosophy of Shankaracharya removes all the weaknesses in human beings; it inspires spiritual aspirants to renounce everything and strive to attain the attributeless and formless Brahman. He laid extreme stress on the path of knowledge. This he did in order to demolish the well-planned structure of logic and arguments of the Buddhists, as well as to humble the unreasonable supremacy which the different Hindu sects had arrogated to themselves. For this reason, the philosophy of Shankaracharya went beyond the comprehension of ordinary minds. Moreover, the “followers” of Shankaracharya gave credence to the thought that religion stands on the sharpness or fineness of intellect than on feelings and sentiments of the heart. Though Shankaracharya himself had composed many melodious and supremely devotional hymns to several gods and goddesses, his “followers” decried devotional sentiments and feelings of the heart. As a consequence, they, on the one hand, failed to grasp and follow the philosophy of Shankaracharya in their lives; on the other, they could not follow the path of devotion either, which was the common man’s way of religion. Such a state of the common man is figuratively depicted in this book in the form of Vyasa’s sorrow. The common man’s despondency as well as longing had deeply stirred the heart of one person, who was perhaps the greatest among all the spiritual geniuses and pundits of those days, and the result was the composition of Bhagavata. It can be said that the bliss Vyasa experienced after he composed Bhagavata became well-known as Bhagavata dharma, or the religion of Bhagavata.

Having composed Bhagavata, Vyasa taught it to his son Shukadeva, who was a born knower of Brahman and a supreme lover of God. Shukadeva narrated it to Emperor Parikshit who, having understood that his death was imminent, had given up everything and had taken to the contemplation on the glories of God. Numerous all-renouncing sages and saints had assembled at that place. From this it is evident that initially Bhagavata was chiefly the scripture of monks and those who had renounced the world, because a monk had narrated it to the assembled monks. But later the followers of Vaishnavism laid chief stress on the devotional aspect of this scripture and, in course of time, Bhagavata became the principle scripture of the householders. However, towards the end of every chapter of Bhagavata we find the following statement: “Composed by Vyasa, here ends this chapter in Bhagavata, which is also known as a great Purana, and is the scripture of monks.” From this it is evident that Bhagavata is the scripture of monks.

Contents

| Introduction | 19 |

| The Speciality of the First Three Verses | 27 |

| The Compiling of Bhagavata and Instructing Shukadeva | 35 |

| Parikshit is Cursed and Shukadeva Narrates Bhagavata | 57 |

| Bhishma Prays to Krishna | 77 |

| Vidura and Uddhava Dialogue - 1 | 95 |

| Vidura and Uddhava Dialogue - 2 | 118 |

| Vidura and Uddhava Dialogue - 3 | 134 |

| Maitreya and Vidura Dialogue | 158 |

| Kapila and Devahuti Dialogue | 174 |

| The Story of Dhruva | 189 |

| The Story of King Prithu | 205 |

| The Story of Prahlada | 221 |

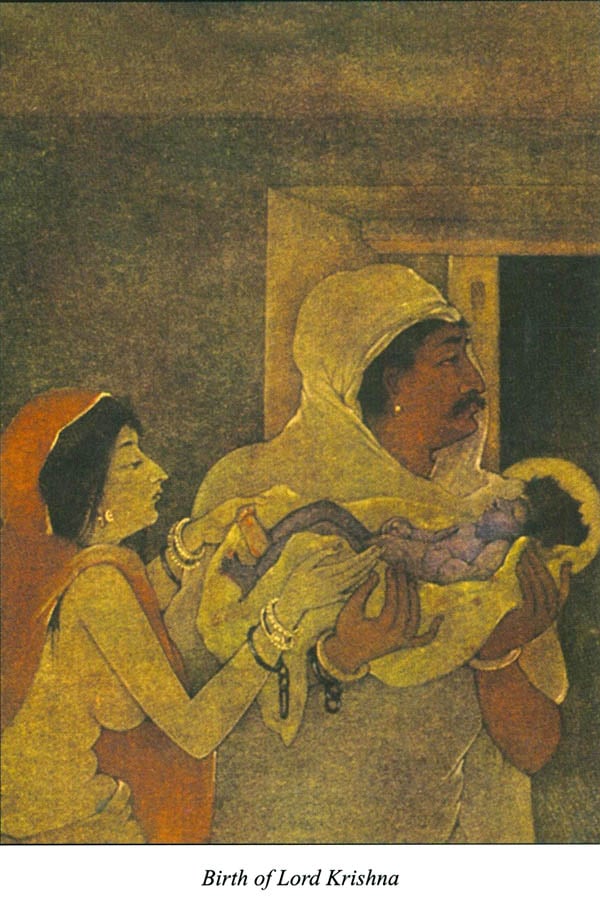

| The Story of Krishna’s Birth | 249 |

| Lord Krishna’s Birth and Kamsa’s Wickedness | 268 |

| Putana’s Liberation | 288 |

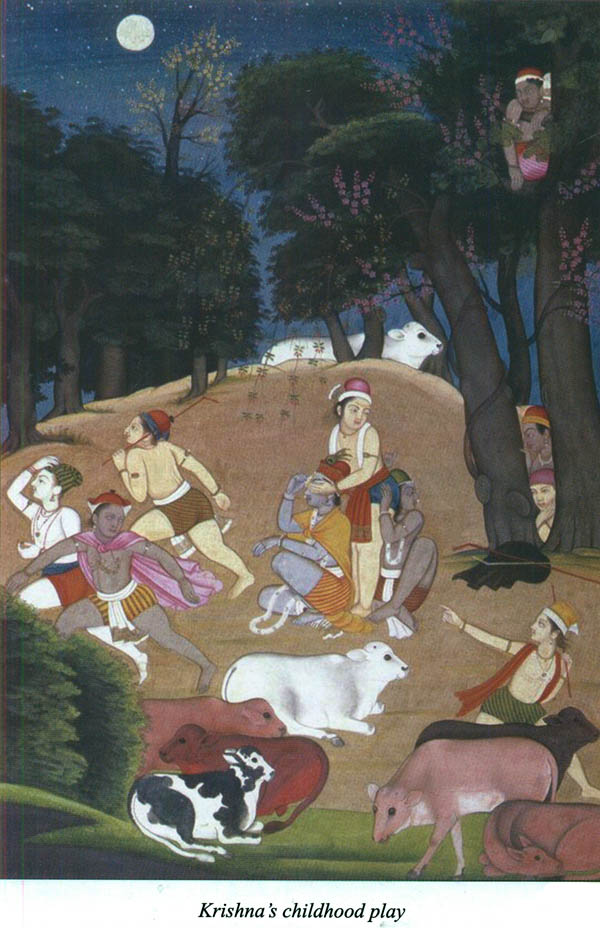

| The Naming Ceremony and Krishna’s Childhood Sports | 302 |

| Binding Krishna | 318 |

| The Story of the Fruit-vending Woman | 334 |

| To Vrindavan from Gokula, and Krishna as the Cowherd Boy | 341 |

| Killing of Aghasura, Brahma’s Trick, and Singing of Krishna’s Praises | 348 |

| Subduing Kaliya | 357 |

| Rasalila - 1 | 374 |

| Rasalila - 2 | 398 |

| Rasalila - 3 | 414 |

| Krishna and Balarama Leave for Mathura | 432 |

| Kamsa’s Death | 449 |

| Uddhava Visits Vraja - 1 | 465 |

| Uddhava Visits Vraja - 2 | 488 |

| Death of Jarasandha and Shishupala | 524 |

| The Solar Eclipse and the Meeting of the Yadavas and the Cowherds at Kurukshetra | 545 |

| The Dialogue between the Nine Sages and Nimi | 563 |

| Krishna’s Resolve to Return to his Abode and Avadhuta’s Teachings | 581 |

| Krishna and Uddhava Dialogue | 593 |

| End of Krishna ‘s Divine Sports and Death of Parikshit | 612 |