God Makes the River to Flow: Sacred Literature of the World

Book Specification

| Item Code: | NAF921 |

| Author: | Eknath Easwaran |

| Publisher: | Jaico Publishing House |

| Language: | English |

| Edition: | 2013 |

| ISBN: | 9788179923306 |

| Pages: | 332 |

| Cover: | Paperback |

| Other Details | 8.5 inch X 5.5 inch |

| Weight | 300 gm |

Book Description

This book is a very personal one. It itself is rather like a river, flowing through a country which is home for all of us but which very, very few have seen: the land of unity, in which all of creation is one and full of God.

There are no boundaries in this land. Those who dwell in it live in a timeless realm beyond distinctions like time, nationality, and language. So in the flow of this book, you will encounter them without regard to such distinctions: Mahatma Gandhi in the company of Saint Teresa of Avila and the Compassionate Buddha, Rabbi Abraham Isaac Kook with Thomas a Kempis, David the Psalmist with the anonymous composer of the Katha Upanishad. At the end of the book you will find brief notes about each mystic and scripture represented here, but within the book no distinction is made with regard to date, place, or religious tradition.

There is one other difference between this book and others I have seen: in addition to being a collection of inspiring spiritual literature, God Makes the Rivers to Flow is an instrument for transforming ones life. I have taught meditation for more than thirty years, and in this book I have collected passages for meditation which, as I can testify from my own experience, have the power to remake personality in the image of ones highest ideals. If this appeals to you, everything you need to start is here.

I have read these passages countless times over the years, yet I never tire of them. With every encounter I find deeper meaning. May you, too, find in them a river of inspiration that flows without end.

Throughout his career as a spiritual teacher, Eknath Easwaran was constantly being asked if this passage or that was appropriate for use in his method of meditation. Always he applied the criteria he had learned to trust in his own practice: the passage had to be positive, practical, universal, and inspiring, and it should come from scripture or from a man or woman whose words and life attested to the realization of the supreme reality that most of the world’s great religions call God. This book began as a collection of such passages - ones he had chosen specifically for use in meditation.

As his audience grew, passages kept flowing in. In the last years of his life he was still learning of new ones and memorizing them for meditation. Many of these, approved by him for his students, have been added to this new edition. Others, contributed after his passing in 1999, have been added with the approval of his wife, Christine Easwaran.

For this edition, the passages have been organized to highlight thematic continuities. Part 1, “At the Source,” features tributes to the springs of our being in the divine ground of existence. Part 2, “Deep Currents,” gathers together ardent prayers of the world s great lovers of God. Part 3, “Joining the Sea,” addresses the challenge of bodily death with soaring statements on immortality.

A concluding chapter, “How to Use This Book,” gives recommendations for using this collection as a daily guide for harnessing the power of sacred words. This transformative potency is detailed in brief catalog of passages that have been found particularly effective in changing negative states of mind into their positive counterparts: anger into compassion, ill will into good will, hatred into love.

Eknath Easwaran is respected around the world as one of the great spiritual teachers. He was professor of English Literature at the University of Nagapur, India, and an established writer, when he came to the United States on the Fulbright exchange program in 1959. As Founder and Director of the Blue Mountain center of Meditation and the Nilgiri Press, he taught the classics of world mysticism and the practice of meditation from 1960 till his death in 1999.

In ancient India lived a sculptor renowned for his life-sized statues of elephants. With trunks curled high, tusks thrust forward, thick legs trampling the earth, these carved beasts seemed to trumpet to the sky. One day, a king came to see these magnificent works and to commission statuary for his palace. Struck with wonder, he asked the sculptor, “What is the secret of your artistry?”

The sculptor quietly took his measure of the monarch and replied, “Great king, when, with the aid of many men, I quarry a gigantic piece of granite from the banks of the river, I have it set here in my courtyard. For a long time I do nothing but observe this block of stone and study it from every angle. I focus all my concentration on this task and won t allow anything or anybody to disturb me. At first, I see nothing but a huge and shapeless rock sitting there, meaningless, indifferent to my purposes, utterly out of place. It seems faintly resentful at having been dragged from its cool place by the rushing waters. Then, slowly, very slowly, I begin to notice something in the substance of the rock. I feel a presentiment... an outline, scarcely discernible, shows itself to me, though others, I suspect, would perceive nothing. I watch with an open eye and a joyous, eager heart. The outline grows stronger. Oh, yes, I can see it! An elephant is stirring in there!

“Only then do I start to work. For days flowing into weeks, I use my chisel and mallet, always clinging to my sense of that outline, which grows ever stronger. How the big fellow strains! How he yearns to be out! How he wants to live! It seems so clear now, for I know the one thing I must do: with an utter singleness of purpose, I must chip away every last bit of stone that is not elephant. What then remains will be, must be, elephant.”

When I was young, my grandmother, my spiritual guide, would often tell just such a story, not only to entertain but to convey the essential truths of living. Perhaps I had asked her, as revered teachers in every religion have been asked, “What happens in the spiritual life? What are we supposed to do?”

My Granny wasn’t a theologian, so she answered these questions simply with a story like that of the elephant sculptor. She was showing that we do not need to bring our real self, our higher self, into existence. It is already there. It has always been there, yearning to be out. An incomparable spark of divinity is to be found in the heart of each human being, waiting to radiate love and wisdom everywhere, because that is its nature. Amazing! This you that sometimes feels inadequate, sometimes becomes afraid or angry or depressed, that searches on and on for fulfillment, contains within itself the very fulfillment it seeks, and to a supreme degree.

Indeed, the tranquility and happiness we also feel are actually reflections of that inner reality of which we know so little. No matter what mistakes we may have made - and who hasn’t made them? - this true self is ever pure and unsullied. No matter what trouble we have caused ourselves and those around us, this true self is ceaselessly loving. No matter how time passes from us and, with it, the body in which we dwell, this true self is beyond change, eternal.

Once we have become attentive to the presence of this true self, then all we really need do is resolutely chip away whatever is not divine in ourselves. I am not saying this is easy or quick. Quite the contrary; it cant be done in a week or by the weak. But the task is clearly laid out before us. By removing that which is petty and self-seeking, we bring forth all that is glorious and mindful of the whole. In this there is no loss, only gain. The chips pried away are of no consequence when compared to the magnificence of what will emerge. Can you imagine a sculptor scurrying to pick up the slivers that fall from his chisel, hoarding them, treasuring them, ignoring the statue altogether? Just so, when we get even a glimpse of the splendor of our inner being, our beloved preoccupations, predilections, and peccadillos will lose their glamour and seem utterly drab.

What remains when all that is not divine drops away is summed up in the short Sanskrit word aroga. The prefix a signifies “not a trace of’; roga means “illness” or “incapacity.” Actually, the word loses some of its thrust in translation. In the original it connotes perfect well-being, not mere freedom from sickness. Often, you know, we say, “I’m well,” when all we mean is that we haven’t taken to our bed with a bottle of cough syrup, a vaporizer, and a pitcher of fruit juice - were getting about, more or less. But perhaps we have been so far from optimum functioning for so long that we dont realize what splendid health we are capable of. This aroga of the spiritual life entails the complete removal of every obstacle to impeccable health, giving us a strong and energetic body, a clear mind, positive emotions, and a heart radiant with love. When we have such soundness, we are always secure, always considerate, good to be around. Our relationships flourish, and we become a boon to the earth, not a burden on it.

Every time I reflect on this, I am filled with wonder. Voices can be heard crying out that human nature is debased, that everything is meaningless, that there is nothing we can do, but the mystics of every religion testify otherwise. They assure us that in every country, under adverse circumstances and favorable, ordinary people like you and me have taken on the immense challenge of the spiritual life and made this supreme discovery. They have found out who awaits them within the body, within the mind, within the human spirit. Consider the case of Francis Bernardone, who lived in Italy in the thirteenth century. I’m focusing on him because we know that, at the beginning, he was quite an ordinary young man. By day this son of a rich cloth merchant, a bit of a popinjay, lived the life of the privileged, with its games, its position, its pleasures. By night, feeling all the vigor of youth, he strolled the streets of Assisi with his lute, crooning love ballads beneath candlelit balconies. Life was sweet, if shallow. But then the same force, the same dazzling inner light, that cast Saul of Tarsus to the earth and made him cry out, “Not I Not I! But Christ liveth in me!” - just such a force plunges our troubadour deep within, wrenching loose all his old ways. He hears the irresistible voice of his God calling to him through a crucifix, “Francis, Francis, rebuild my church.” And this meant not only the Chapel of San Damiano that lay in ruins nearby, not only the whole of the Church, but that which was closest of all - the man himself.

This tremendous turnabout in consciousness is compressed into the Prayer of Saint Francis. Whenever we repeat it, we are immersing ourselves in the spiritual wisdom of a holy lifetime. Here is the opening:

These lines are so deep that no one will ever fathom them. Profound, bottomless, they express the infinity of the Self. As you grow spiritually, they will mean more and more to you, without end.

But a very practical question arises here. Even if we recognize their great depth, we all know how terribly difficult it is to practice them in the constant give-and-take of life. For more than twenty years I have heard people, young and old, say that they respond to such magnificent words - that is just how they would like to be - but they don’t know how to do it; it seems so far beyond their reach. In the presence of such spiritual wisdom, we feel so frail, so driven by personal concerns that we think we can never, never become like Saint Francis of Assisi.

I say to them, “There is a way.” I tell them that we can change all that is selfish in us into selfless, all that is impure in us into pure, all that is unsightly into beauty. Happily, whatever our tradition, we are inheritors of straightforward spiritual practices whose power can be proved by anyone. These practices vary a bit from culture to culture, as you would expect, but essentially they are the same. Such practices are our sculptors tools for carving away what is not-us so the real us can emerge.

Meditation is supreme among all these tested means for personal change. Nothing is so direct, so potent, so sure for releasing the divinity within us. Meditation enables us to see the lineaments of our true self and to chip away the stubbornly selfish tendencies that keep it locked within, quite, quite forgotten.

In meditation, the inspirational passage is the chisel, our concentration is the hammer, and our resolute will delivers the blows. And how the pieces fly! A very small, fine chisel edge, as you know, can wedge away huge chunks of stone. As with the other basic human tools - the lever, the pulley - we gain tremendous advantages of force. When we use our will to drive the thin edge of the passage deep into consciousness, we get the purchase to pry loose tenacious habits and negative attitudes. The passage, whether it is from the Bhagavad Gita or The Imitalion of Christ or the Dhammapada of the Buddha, has been tempered in the flames of mystical experience, and its. bite will... well, try it and find out for yourself just what it can do. In the end, only such personal experience persuades.

Now if we could hold an interview with a negative tendency, say, Resentment, it might say, “I don t worry! I’ve been safely settled in this fellow’s mind for years. He takes good care of me - feeds me, dwells on me, brings me out and parades me around! All I have to do is roar and stir things up from time to time. Yes, I’m getting huge and feeling grand. And I’m proud to tell you there are even a few little rancors and vituperations running around now, spawned by yours truly!” So he may think. But I assure you that when you meditate on the glorious words of Saint Francis, you are prying him loose. You are saying in a way that goes beyond vows and good intentions that resentment is no part of you. You no longer acknowledge its right to exist. Thus, we bring ever more perceptibly into view our divine self. We use something genuine to drive out impostors that have roamed about largely through our neglect and helplessness.

To meditate and live the spiritual life we needn’t drop everything and undertake an ascent of the Himalayas or Mount Athos or Cold Mountain. There are some who like to imagine themselves as pilgrims moving among the deer on high forest paths, simply clad, sipping only at pure headwaters, breathing only ethereal mountain air. Now it may sound unglamorous, but you can actually do better right where you are. Your situation may lack the grandeur of those austere and solitary peaks, but it could be a very fertile valley yielding marvelous fruit. We need people if we are to grow, and all our problems with them, properly seen, are opportunities for growth. Can you practice patience with a deer? Can you learn to forgive a redwood? But trying to live in harmony with those around you right now will bring out enormous inner toughness. Your powerful elephant will stir and come to life.

The old dispute about the relative virtues of the active way and the contemplative way is a spurious one. We require both. They are phases of a single rhythm like the pulsing of the heart, the indrawing and letting go of breath, the ebb and flow of the tides. So we go deep, deep inwards in meditation to consolidate our vital energy, and then, with greater love and wisdom, we come out into the family, the community, the world. Without action we lack opportunities for changing our old ways, and we increase our self-will rather than lessen it; without contemplation, we lack the strength to change and are blown about by our conditioning. When we meditate every day and also do our best in every situation, we walk both worthy roads, the via contemplativa and the via activa.

The passages in this book are meant for meditation. So used, they can lead us deep into our minds where the transformation of all that is selfish in us must take place. Simply reading them may console us, it may inspire us, but it cannot bring about fundamental, lasting change; meditation alone does that. Only meditation, so far as I know, can release the inner resources locked within us, and put before us problems worthy of those resources. Only meditation gives such a vital edge to life. This is maturity. This is coming into our own, as our concerns deepen and broaden, dwarfing the personal satisfactions - and worries - that once meant so much to us.

If you want to know how to use inspirational passages in meditation, please read the instructions on page 259 of this book. The basic technique, duration and pace, posture, and place are all taken up. You will also find there the outline of a complete eight-point program for spiritual living, including the use of the mantram, slowing down, and achieving one-pointed attention. For a more detailed introduction to this program of self-transformation, I refer you to my other books, especially Meditation. I would like here, though, to say a bit about the criteria I have used in selecting these particular passages.

We wouldn’t use a dull chisel or one meant for wood on a piece of stone, and we should use suitable passages for meditation. Were not after intellectual knowledge, which helps us understand and manipulate the external world. We seek spiritual wisdom, which leads to inner awareness. There, the separate strands of the external world - the people, the beasts and birds and fish, the trees and grasses, the moving waters and still, the earth itself - are brought into one great interconnected chord of life, and we find the will to live in accordance with that awareness. We find the will to live in perpetual love. I think you’ll agree there are very few books which can ever lead us to that.

The test of suitable meditation passages is simply this: Does the passage bear the imprint of deep, personal spiritual experience? it the statement of one who went beyond the narrow confines of past conditioning into the unfathomable recesses of the mind, there to begin the great work of transformation? This is the unmistakable stamp of authenticity. Only such precious writings can speak directly to our heart and soul. Their very words are invested with validity; we feel we are in the presence of the genuine.

The scriptures of the world’s religions certainly meet this test, and so do the statements of passionate lovers of God like Saint Teresa, Kabir, Sri Ramakrishna, Ansari of Herat. And whatever lacks this validation by personal experience, however poetic or imaginative, however speculative or novel, is not suited for use in meditation.

But there is another thing to be considered: Is the passage positive, inspirational, life-affirming? We should avoid passages from whatever source that are negative, that stress our foolish errors rather than our enduring strength and wisdom, or that deprecate life in the world, which is precisely where we must do our living. Instead, let us choose passages that hold steadily before us a radiant image of the true Self we are striving to realize.

For the great principle upon which meditation rests is that we become what we meditate on. Actually, even in everyday life, we are shaped by what gains our attention and occupies our thoughts. If we spend time studying the market, checking the money rates, evaluating our portfolios, we are going to become money-people. Anyone looking sensitively into our eyes will see two big dollar signs, and well look out at the world through them, too. Attention can be caught in so many things: food, books, collections, travel, television. The Buddha put it succinctly: “All that we are is the result of what we have thought.”

If this is true of daily life, it is even more so in meditation, which is concentration itself. In the hours spent in meditation, we are removing many years of the “what we have thought.” At that time; we need the most powerful tools we can find for accomplishing the task. That is why, in selecting passages, I have aimed for the highest the human being is capable of, the most noble and elevating truths that have ever been expressed on this planet. Our petty selfishness, our vain illusions, simply must and will give way under the power of these universal principles of life, as sand castles erode before the surge of the sea.

Specifically, what happens in meditation is that we slow down the furious, fragmented activity of the mind and lead it to a measured, sustained focus on what we want to become. Under the impact of a rapidly-moving, conditioned mind, we lose our sense of freely choosing. But, as the mind slows down, we begin to gain control of it in daily life. Many habimal responses in what we eat, see, and do, and in the ways we relate to people, come under our inspection and governance. We realize that we have choices. This is profoundly liberating and takes away every trace of boredom and depression.

The passages in this collection have been drawn from many traditions, and you’ll find considerable variety among them. Some are in verse, some in prose; some are from the East, some from the West; some are ancient, some quite recent; some stress love, some insight, some good works. So there are differences, yes, in tone, theme, cultural milieu, but they all have this in common: they will work.

As your meditation progresses, I encourage you to build a varied repertory of passages to guard against overfamiliarity, where the repetition can become somewhat mechanical. In this way, you can match a passage to your particular need at the time - the inspiration, the reminder, the reassurance most meaningful to you.

Nearly everyone has had some longing to be an artist and can feel some affinity with my Granny’s elephant sculptor. Most of us probably spent some time at painting, writing, dancing, or music-making. Whether it has fallen away, or we still keep our hand in, we remember our touches with the great world of art,, a world of beauty and harmony, of similitudes and stark contrasts, of repetition and variation, of compelling rhythms like those of the cosmos itself. We know, too, that while we can all appreciate art, only a few can create masterworks or perform them as virtuosi.

Now I wish to invite you to undertake the greatest art work of all, an undertaking which is for everyone, forever, never to be put aside, even for a single day. I speak of the purpose of life, the thing without which every other goal or achievement will lose its meaning and turn to ashes. I invite you to step back and look with your artist’s eye at your own life. Consider it amorphous material, not yet deliberately crafted. Reflect upon what it is, and what it could be. Imagine how you will feel, and what those around you will lose, if it does not become what it could be. Observe that you have been given two marvelous instruments of love and service: the external instrument, this intricate network of systems that is the body; the internal, this subtle and versatile mind. Ponder the deeds they have given rise to, and the deeds they can give rise to.

And set to work. Sit for meditation, and sit again. Every day without fail, sick or well, tired or energetic, alone or with others, at home or away from home, sit for meditation, as great artists throw themselves into their creations. As you sit, you will have in hand the supreme hammer and chisel; use it to hew away all unwanted effects of your heredity, conditioning, environment, and latencies. Bring forth the noble work of art within you! My earnest wish is that one day you shall see, in all its purity, the effulgent spiritual being you really are.

| About This Book | 13 | |

| Introduction | 15 | |

| Part 1 | At the Source | 27 |

| Part 2 | Deep Currents | 99 |

| Part 3 | Joining the Sea | 175 |

| The Message of the Scriptures | 255 | |

| An Eight Point Program | 259 | |

| How to Use This Book | 265 | |

| Using Inspirational Passages to Change Negative Thinking | 277 | |

| Notes | 283 | |

| Glossary | 321 | |

| Acknowledgments | 323 | |

| Index by Author & Source | 325 | |

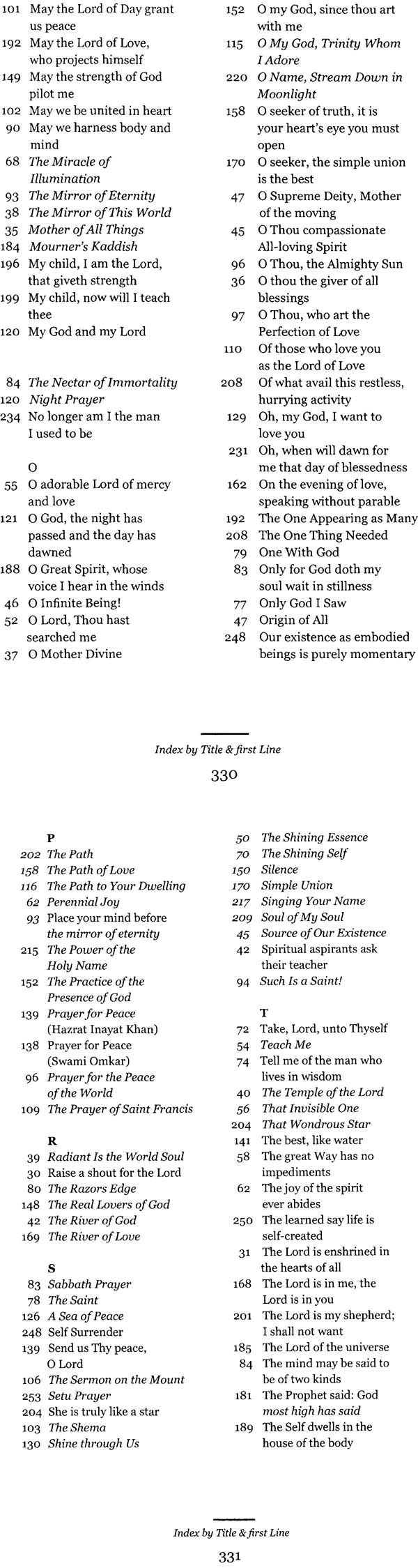

| Index by Title & First Line | 327 | |