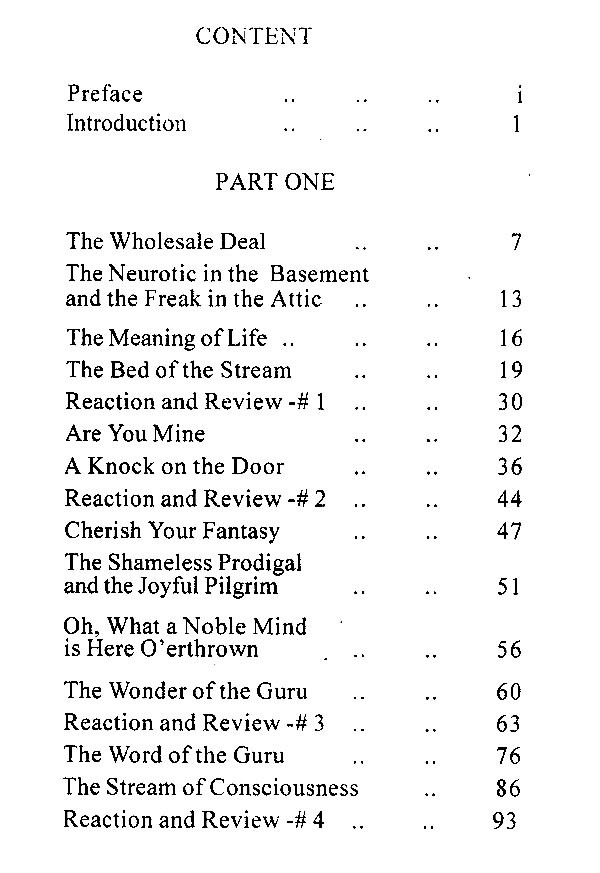

In The Stream of Consciousness

Book Specification

| Item Code: | AZC832 |

| Author: | Nitya Chaitanya Yati |

| Publisher: | Narayana Gurukula, Kerala |

| Language: | ENGLISH |

| Edition: | 2004 |

| Pages: | 116 |

| Cover: | PAPERBACK |

| Other Details | 8.50x5.50 inches |

| Weight | 156 gm |

Book Description

Nitya Chaitanya Yati (1924-1999) for over twenty five years was the Guru and head of the Narayana Gurukula Movement, a worldwide contemplative spiritual fraternity to which several scores of people have dedicated themselves to actualize what they understand as the fulfillment of their lives and with which several million people affiliate to keep themselves resonant with what has always been dearest to humankind, such as love without frontiers and the beauty that enhances the visions of seers, poets, artists and scientists.

From underground springs to mighty rivers, everywhere on earth the water that falls from the sky is flowing toward the oceans. The sun's heat evaporates water out of the ocean, lifting the vapor heavenward. The winds gather the vapor together as clouds, which return the life-giving droplets back to earth as rain. On the ground the drops reunite, forming pools, streams, creeks and rivers, all once again winding their way back to their source. It is as if all the four elements are in a conspiracy to perpetuate the cycle of the emergence and return of all forms of life.

From ancient mythology and folklore to modern pop music lyrics, again and again we find life itself treated as a river. Always flowing and changing, now turbulent, now calm, many streams joining together to form single bodies, all of it moving at its own pace back to the sea where the individuality of each separate stream is remerged in the totality from which countless future vaporous clouds, drops, and streams will again be brought forth.

The common denominator linking cloud, rain, pool, river and ocean is Water. The ever-flowing water of our life is Consciousness. Whether life savors bland, sweet or bitter, it is our own consciousness that is at once both the taster as well as that which is itself tasted. Christ must have had this in mind when he remarked:

"Ye are the salt of the earth: but if the salt should have lost its savor, wherewith shall it again be salted? It is henceforth good for nothingbut to be cast out and to be trodden under foot of men."

In its onward flow water knows many conditions. When it is calm and clear, it is capable of beautifully mirroring the sky and the surroundings from which it came, as well as the sun which illuminates and enlivens all this. The same water, when turbulent, reflects the sky, the surroundings and the sun in an unstable and distorted way. The water may sometimes even become so muddied that it becomes opaque, and nothing can be mirrored in it at all.

This book was initially conceived as an investigation into the nature and dynamics of that very consciousness which in turn raises us to the heights of sublimity and plunges us to the depths of despair, which creates its own meaning or sense of meaninglessness, which has no form and yet is ever ready to assume any form. It is not a philosophical treatise, through a sound philosophical base is implied herein. The problems it deals with, although universal, are in no way treated hypothetically. The book in general and each chapter in particular grew out of the burning needs of real people who approached Guru Nitya for help.

Nitya's style is often to give a talk to a lass that is simultaneously transcribed by one or more students. Later he goes over it to correct errors and make further comments. In addition, during the period that this book was being written, he would hold a session for the students to ask questions about the material. In the classic format of a guru/disciple dialogue. he would answer the questions extemporaneously. The incisive querying of disciples is the time-honored method of eliciting wisdom from a guru, in whom insights tend to be retained unless they are called upon to be brought forth. The four Reaction and Review sections of the book are the record of these encounters.

As is often the case is such situations, the answers the guru presents bear on the spiritual problems of the questioner that may or may not have been directly implied the actual question. It is a real mystery that the couple dozen of us who had the good fortune to sit in on the dictations and question and answer sessions each felt that the message contained was speaking directly and personally to us.

The talks and interchanges contained herein took place in 1975, in and around Portland State University in Oregon, United States. Guru Nitya's primary teacher was Nataraja Guru, whose teacher was the great Narayana Guru. Both these other gurus are mentioned in Part Two of the work, which is a collection of teaching stories.

In the Upanishads it is said that in order to know the nature of water, it is not necessary to drain the seven seas; but rather if one thoroughly understands a single drop, he knows all water. Like that, this book is not an objective study of anything "out there." Each reader is invited to make the subject and the object under study one and the same.

According to John Locke, we come to this life with a blank slate of a mind on which nothing is scribbled. He called it a tabula rasa. Many of his contemporaries did not agree with him. I don't want to get into a controversy about it at this point, but at least one thing I know for sure is that no writer sits with a tabula rasa when he is about to write a book. He has in his mind the theories he has heard and the arguments that were put forth to support or to oppose such theories. He has his own observations and questions. On his own he must have been exercising some suitable method to attack his particular problem and present it in a convincing manner. He must be aware of rival theories and the merits and demerits of several other stands. Above all this, he will have his own normative notion that gives him certitude of the truth he wants to underline and share with others.

If the writer is not fanatical and has an open mind, he won't fail to see that there are several other points of view from which one can look at the issue under consideration. Consequently he should also believe in the complementarity of the points of view from different vantage points. In spite of the advantage of knowing a subject from every possible angle, historical settings and the natural limitations of a mind tied down to a body that can transport itself only in a limited region of time and space and which is favored to live in no more than a few ethnic circles, make it inevitable that the writer be content with the one standpoint where he can feel most comfortable.

The grassroots of the present writer are in India, where several hierarchies of teachers have been busying themselves with the search for the meaning of life. They have evolved a number of models of perfection which approximate the several shades of meaning they have arrived at. The most important among these models are those of the yogi, one of harmonized mind who lives in a state of equipoise, and the inani, a seer of clear vision who silently witnesses the real and passively participates in the demands of the actual.

The yogi image dates back to the prehistoric era. A seal depicting a yogi, estimated to have been made around 2500 BC, was found in the archeological site of Mohenjo Daro, which is situated in what is today Pakistan.

The system of philosophy that upholds the image of the jnani, the wise rishi, is the school of Vedanta. Yoga and Vedanta are classified among the six orthodox schools of Indian Philosophy. The six schools are more conveniently grouped as three pairs of systems: Nyaya and Vaiseshika, Samkhya and Yoga, and Mimamsa and Vedanta.

Nyaya is a school of logic which gives priority in its system to the category of the general or the collective. Vaiseshika is a complementary school of logic giving primacy to the specific constituents of truth. It has also developed a method of analysis to categorize and classify all elements that constitute the field of human experience.

Samkhya is a school that has reduced the visibles into calculables. It divides the world into twenty-four categories originating from a binary cause. According to the Samkhya system, the world is essentially a "coming together of things," so there is no need for a God or a Creator. While the school of Yoga generally follows the epistemology of the Samkhya system, it does accept the notion of God in a philosophically limited sense. This brings it closer to the spirit of the Upanishads.

Mimamsa means a critique. Mimamsa and Vedanta are otherwise called purva mimamsa, anterior criticism, and uttara mimamsa, posterior criticism. Purva mimamsa is a critique of action dynamics, especially of ritual and of the semiosis of mantras, and Vedanta is a critique of knowledge. Happily, three eminent masters of Vedanta gave their best attention to the yoga aphorisms of Patanjali, the basic exposition of Yoga. They have each written a commentary on Yoga by complementing its teaching with the wisdom of Vedanta.

From the days of Sankara in the eighth century through the Mogul period in the sixteenth century, there was an active exchange of ideas and counter-criticisms between the scholars of the six schools of Indian philosophy and the exponents of the four schools of Buddhism, the two main schools of Jainism, and the Indian school of materialism. The two schools that have withstood the onslaught of time and the decadence through which India has passed during the last five centuries are the schools of Yoga and Vedanta.