Lives of The Nuns (Biographies of Chinese Buddhist Nuns from the Fourth to Sixth Centuries)

Book Specification

| Item Code: | NAS061 |

| Author: | Kathryn Ann Tsai |

| Publisher: | Sri Satguru Publications |

| Language: | English |

| Edition: | 1995 |

| ISBN: | 8170304652 |

| Pages: | 202 |

| Cover: | HARDCOVER |

| Other Details | 8.50 X 5.50 inch |

| Weight | 340 gm |

Book Description

Among the stories of the Buddhist life well lived are entertaining tales that reveal the wit and intelligence of these women in the face of un-savory officials, highway robbers, even fawning barbarians. When Ching-ch'eng and a fellow nun, renowned for their piety and strict asceticism, are taken to "the capital of the northern barbarians" and plied with delicacies,, the women "besmirch their own reputation" by gobbling down the food shamelessly. Appalled by their lack of manners, the disillusioned barbarians release the nuns, who return happily to their convent.

Lives of the Nuns gives readers a glimpse into a world long vanished yet peopled with women and men who express the same aspirations and longing for spiritual enlightenment found at all times and in all places.

Buddhologists, sinologists, historians, and those interested in religious studies and women's studies will welcome this volume, which includes annotations for readers new to the field of Chinese Buddhist history as well as for the specialist.

Kathryn Ann Tsai received a Ph.D. in East Asian languages and literature from the University of Wisconsin. She has taught at the University of British Columbia and the University of Michigan on a visiting basis.

The Chinese Buddhist canon of scripture includes a unique and remarkable text, the Pi-ch'iu-ni chuan, or Lives of the Nuns (hereafter Lives), a collection of chronologically organized biographies of sixty-five Chinese Buddhist nuns.' More than a mere collection of biographies, their dates cover the period of the founding and establishing of the Buddhist monastic order for women from the early fourth century to the early sixth century. The Lives allows us to see the development of monastic life for women in China from its beginnings. Shih Pao-ch'ang, who compiled the book in or about A.D. 516, selected his subjects with careful discrimination and produced a document of interest for his readership, whom he presumably had hoped to spur on to greater efforts in the Buddhist life (see Pao-ch'ang's preface).' Fifteen hundred years later the biographies are of interest to us for very different reasons. We see in hindsight many features of the early history of Buddhism in China and many reasons why women of that time might take up the life of a Buddhist nun.

Although many of the Buddhist texts, both Disciples' Vehicle and Mahayana, or Great Vehicle,4 contain virulent misogynistic sections, there were in fact no doctrinal reasons that denied enlightenment and, later, Buddhahood to women.

The women of China ardently embraced Mahayana Buddhism and its large number of texts, although only a small number of these scriptures became extremely popular—such as the Flower of the Law, Vimalakirti, Perfection of Wisdom, and the Amita or Pure Land texts. The most significant obstacle to a woman's entering the Assembly of Nuns was men rather than doctrine. The Assembly of Nuns was dependent on the Assembly of Monks for several of their required rites and rituals. The reverse was not the case.

Of the three types of Buddhist writings—the Buddha's own word (sutra), the commentaries (shastra), and the monastic code (vinaya) that tied the Assembly of Nuns to the Assembly of Monks—the Buddha's word and the commentaries were eagerly translated; however a lack of adequate vinaya texts in the early history of Buddhism in China hindered the establishment and development of the monastic order for women.

The Buddha Shakyamuni lived from about 560 B.c. to 480 B.c. in northern India.' The way of life that he founded was from the first both a monastic and a missionary religion. Spreading far beyond its homeland, about five hundred years after the death of the Buddha, Buddhism traveled quietly along the Silk Road into China.

The first positive evidence for Buddhism in China dates to A.D. 65 in the Latter Han dynasty (25-220). There is a brief reference in the Hou han shu (History of the Latter Han dynasty)e to Buddhism together with Taoism in the city of P'eng-ch'eng, a city that may be considered the easternmost terminus of the Silk Road (see map).' The next positive reference to Buddhism in China dates to the middle of the second century, in the northern city of Lo-yang, where foreign missionary monks and their Chinese followers set up a translation center.

Unfortunately, by the middle of the second century the Latter Han dynasty had begun the decline that ended with its collapse in A.D. 220. Rebellions, contenders for the throne, and nomadic tribes riding down from the north pressed the agrarian Chinese and created great social upheaval: families were separated; many became refugees; famine and disease were widespread; and there was general social and political chaos. The Great Wall had been built as a bulwark against the nomads, but it was only as strong as the defending dynasty.

Undaunted by all the difficulties in China, Buddhist missionaries continued to arrive and continued to translate scriptures." They brought a religion that offered consolation for a very uncertain world. The Buddhist emphasis on the world's illusory quality attracted many more followers than perhaps it would have in a time of peace and tranquility. In a time of social tranquility it could have ended up as a sect of Taoism, with which it was often associated during its early years in China.

The wars, however, continued. A trio of ill-starred dynasties tried to restore the old Han empire, but none could prevail over another or over the nomads until the Chin dynasty (265-317/317-420) briefly united the country in A.D. 280.13 But that unity was neither long nor peaceful. The nomadic tribes sacked the two major northern capital cities of Lo-yang in 311 and Ch'ang-an in 316. In 317 the court of the Chin dynasty, along with many others, fled to the south. The loss of northern China to the barbarians began the division of the country into the Northern and Southern dynasties. A relatively stable, non-Chinese dynasty fringed with many, often ephemeral barbarian kingdoms controlled the north, while a series of short-lived Chinese dynasties controlled the south. This division would last for several centuries until one ruler reunited the country in 589, long after the Lives was completed.

Because the Confucianism that had been the philosophical foundation of the Han dynasty had failed to prevent the disintegration of the empire, it lost the allegiance of many of the educated elite. Men began to look elsewhere for a way to order their lives and their-land. The old loyalties were loosened, giving both Buddhism and Taoism a greater scope for development and expansion. Buddhism held its own and gradually became less exotic sight and in addition became separated more and more from Taoism, with which, in the early days, it had often been confused and mingled. In both north and south, Buddhism gradually became a part of upper-class life, but, after the shock of losing the heart of the empire to barbarians and the flight to the south in 317, the Chinese embraced Buddhism with a positive passion that continued throughout the time of the Northern and Southern dynasties. The Buddhist institutions that both immigrant and native worked to establish in the lower Yangtze River valley were planted so deeply that, despite the vicissitudes of decline, rebellion, and persecution over the centuries, these institutions always revived to regain their vitality.'

Not everyone during the Northern and Southern dynasties in China welcomed the new religion. Despite many superficial similarities between Buddhism and Taoism, and despite much mutual influence in their development, Taoists saw the foreign religion as a direct rival.

Buddhism and Taoism appealed to the same people: those wanting metaphysical stability or a sense of permanence in a turbulent age, those wanting very long life or immortality, those seeking a way of life different from, or at the least a respite in private life from, the Confucian ideal of social and familial obligations and public service. Furthermore, Buddhists and Taoists practiced similar arts. Magic, for example, played an important role in the initial acceptance of Buddhism, and Taoist practitioners found themselves facing tough adversaries." The biography of Tao-jung (no. 10) illustrates one such encounter.

For the most part, any hostilities that arose were expressed verbally, but once in a great while partisans felt compelled to take stronger action. The biography of Tao-hsing (no. 9) clearly shows the rivalry when a Taoist woman poisoned a Buddhist nun because "the people of the region had respected the Taoist woman and her activities very much until Tao-hsing's Way of Buddhism eclipsed her arts." The rivalry did not go in one direction only. In a collection of biographies of Taoist women, we learn that a Taoist nun was accosted by knife-wielding Buddhist monks."

Confucianism was the far more serious threat to Buddhism, how-ever, because it had shaped the institutions at the heart of Chinese life: the imperial government and the family. Buddhism ran directly counter to Confucian norms in many aspects of life, one of the most important being that the monastic life required celibacy. In traditional China a good son had the duty to marry and produce male offspring to continue the family line. Shaving the head, also a requirement of Buddhist monastic life, ran contrary to Confucian principles because one's hair was a gift from one's parents and so was not to be cut off. In death, too, there was conflict. Cremation, the deliberate destruction of the body, was abhorrent to those Chinese who considered the body to be a gift from one's father and mother. Buddhists had to try to convince the population at large, as well as individual distraught parents, that a child's entering the Buddhist monastic life not only was not at all unfilial but also was a superior kind of filial piety. The discussion in the biography of An Ling-shou (no. 2) illustrates this well.

A millennium and a half ago there lived in China some remarkable women who cast aside the fetters of the world to become Buddhist nuns. Lives of the Nuns preserves the memory of their lives and deeds and gives us a look into a world that is foreign, exotic, and now vanished; yet, that world is far less alien than we might first think, for it is peopled with men and women who express the same emotions—the same desires, aspirations, or longings for spiritual enlightenment—as those found at all times and in all places. Furthermore, the character of these nuns who lived during dangerous and chaotic times can instruct us who also live in such times. We need not be Chinese Buddhists of the sixth century to be charmed by the nun Hui-chan's insouciant bravery (no. 7), or to be moved by Chih-hsien's fearless integrity (no. 3), or to smile at Ching-ch'eng's clever ruse (no. 28). And we who have in this generation seen Buddhist monastics offer their bodies as a sacrifice by fire will feel kinship with the religious and laity of long ago who, when they learned that T'an-chien (no. 46) had offered her body by fire to the Buddha, "lamented, their cries reverberating through the mountains and valleys."

This translation of Lives of the Nuns, a major revision of an original translation done as part of my doctoral dissertation for the University of Wisconsin, was prepared with both the general reader and the scholar in mind in the hope that those who have no special back-ground in the subject may take up the material and read with pleasure and understanding, while the scholars in the field may also enjoy the Lives.

Because the biographies are often concise to the point of obscurity, and because allusions, references, names, and places familiar to the Chinese reader of nearly fifteen hundred years ago are simply not going to be clear to the present-day English-speaking reader, the translator has taken the liberty of adding to the text of the biographies bracketed phrases or even sentences necessary to provide a smoother narrative. Any material that cannot be worked into the biography itself is found in the notes.

To provide a sense of geographic direction, place-names are supplemented with brief phrases indicating where they were in China or where they were in relation to the southern capital, which, as the major city of the southern dynasties, makes an obvious reference point. A map of China, showing many of the places mentioned in the biographies, is also included. It should be kept in mind that, whenever a biography mentions the place where the woman's family came from, it frequently means the place from which the family had emigrated several generations previously. When a place-name cannot be located with reasonable certainty, no attempt is made to locate it.

To clarify relationships or to bring out more clearly the point of a nun's connection with particular individuals, named persons, when-ever possible, are identified by a brief phrase in the translation. Additional information, if any, appears in the notes. Those individuals who are otherwise unknown will not be annotated.

To help readers fix the events in time, dates of birth and death are given when known and, for emperors, dates of birth, beginning of reign, and death.

The bibliography of sources, reference works, and readings describes the books mentioned in the notes, those used as sources and references for the preparation of the translation, and those that readers might find of further interest.

Appendix A is a more technical discussion of the history, sources, and literary prototypes for the text of the Lives.

The romanization system used for transcribing the Chinese charac-ters is a modification of the Wade-Giles system, chosen because the English-language references and suggested further readings also use this system, thereby creating a consistency that the reader might find helpful.

Words of Sanskrit origin are transcribed using the long marks (macrons) over the vowels but not the retroflex marks under certain consonants. The letter combination sh represents both the consonant often transcribed as an s with the acute accent and the consonant s often transcribed with the retroflex dot underneath. The letter combination ch represents what is often written only as the letter c. The letter n before g, k, or h represents what is often written as an m. These differences should be noted when trying to find in other readings the words or titles of Sanskrit origin used in the Lives of the Nuns.

The nuns' personal names have been transliterated, with a translation of the name appearing only in the glosses that begin the individual biographies. Names of convents and monasteries have been translated to provide the reader with a respite from the many Chinese names and in some instances to make clear the point a biography is trying to make concerning the choice of a name for the convent, as for example, biography 5. Place-names have been transliterated, except for some names of mountains that can be straightforwardly translated into English. The names of the two most famous rivers in China are given in the form familiar to English-speaking readers—that is, the Yellow and the Yangtze rather than the Ho and the Chiang.

Thanks are due to the late Arthur E. Link for having introduced me, many years ago, not only to the Pi-ch'iu-ni chuan but also to the world of medieval China, to the late Richard H. Robinson for having supervised my initial work, and to the late Holmes Welch'for having provided opportunities for further study and research.

I must also thank a colleague whom I have never met, Li Tung-hsi, of the Chinese Buddhist Association in Peking, whose own English translation of the Pi-ch'iu-ni chuan I reviewed in 1985. Although I would have preferred speaking with him personally, having his translation at hand meant that I was able, in a sense, to ask his opinion about any phrase or sentence in the text. Because we are working with difficult and often ambiguous material, it is to be expected that we will not always agree.

A heartfelt thank you I offer to Sharon Yamamoto of University of Hawaii Press not only for her initial interest but also for her encouragement and for her well-chosen suggestions for improving the book.

To my husband, Tsai Hsiang-jen, I owe deep and deserved thanks in recognition of his patient endurance as well as his very concrete help in more ways than I can count.

To the late Anna Katharina Seidel of the Institut du Hobogirin in Kyoto, for her help, criticism, and especially for her unfailingly kind generosity, I owe a debt of gratitude that can never be adequately repaid. Whatever is good in this work is hers, and to her I dedicate Lives of the Nuns.

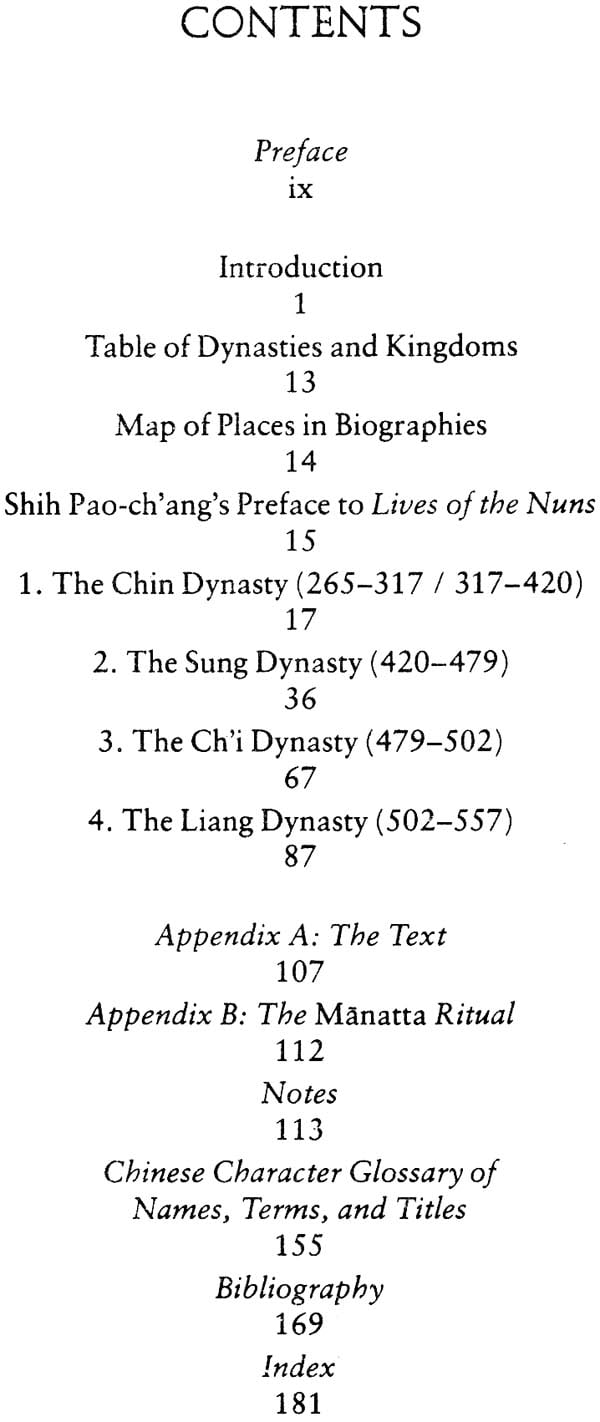

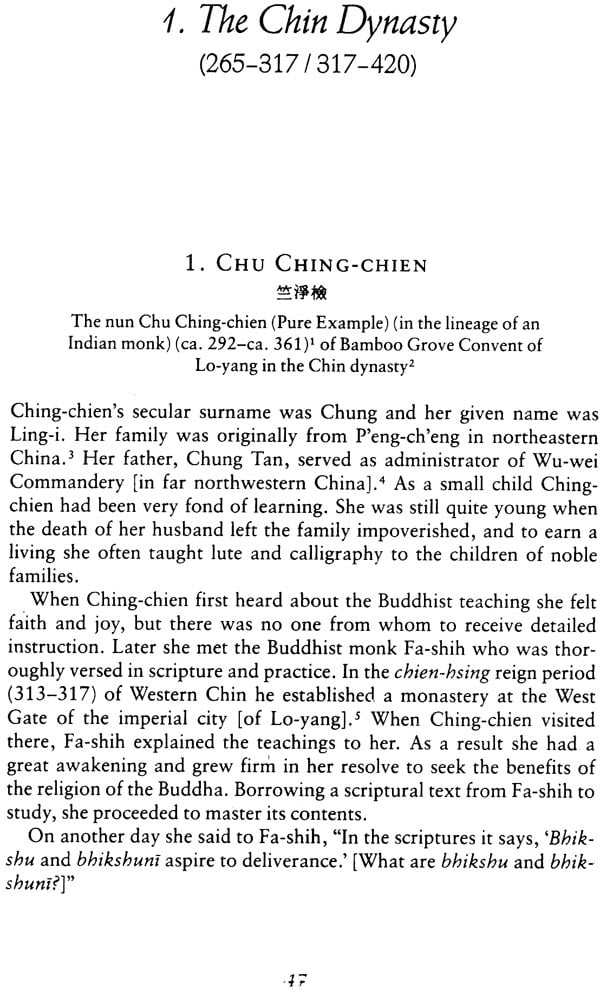

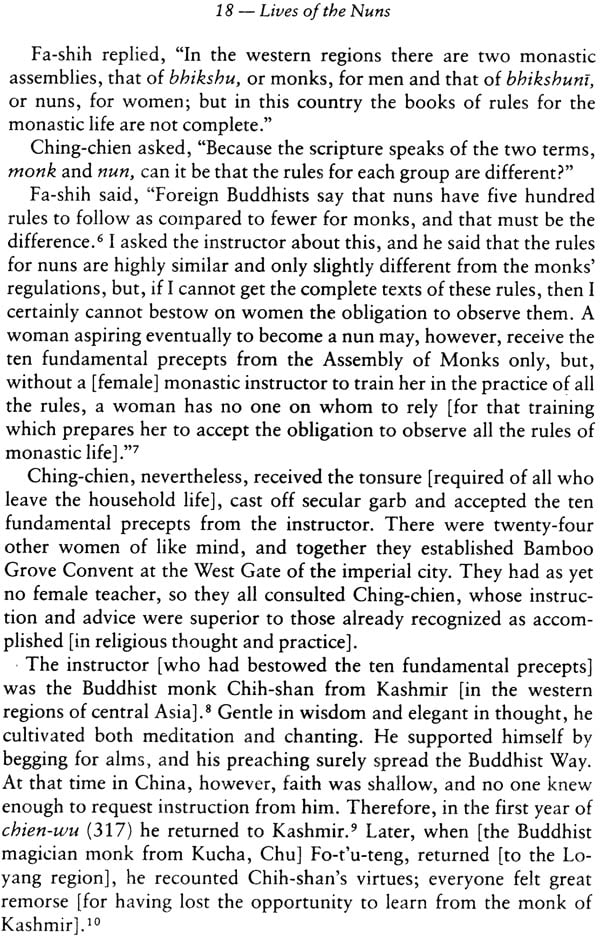

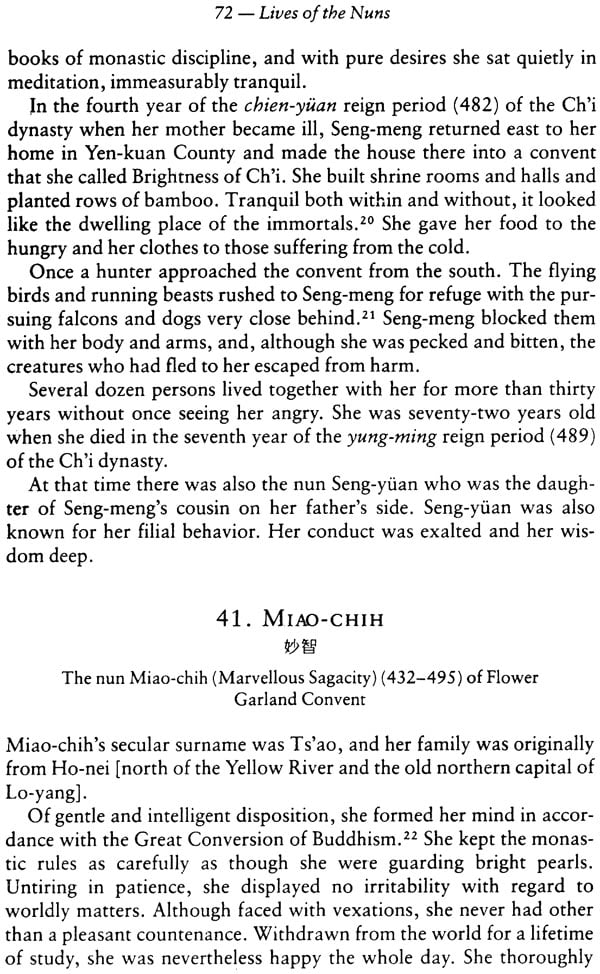

**Contents and Sample Pages**