About the Book Over 30 years ago the authors of this book produced a provocative critique of survey research methods that were widely used for development planning in Nepal. Their innovative study demonstrated that survey methods generated significantly inaccurate and misleading data. This work further exposed numerous socio-cultural and linguistic factors that accounted for this high accumulation of non-sampling errors in the survey process. Today in Nepal and elsewhere, national and international development agencies continue to rely heavily on survey research to guide their policies, plans and projects. This second edition of The Use and Misuse of Social Science Research in Nepal re-opens the important issues of how and why survey methods must be modified and supplemented with other methods in order to produce valid and useful data in the context of developing countries such as Nepal. This current edition of the book includes Foreword by Prof. Chaitanya Mishra and Preface and Introduction, which places the original study in a contemporary perspective with respect to theory and practice in social sciences.

About the Author J. Gabriel Campbell, Ph.D, is Senior Fellow at The Mountain Institute and was Director General of International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development (ICIMOD) from 2000 to 2007. He has worked as a development anthropologist in the Himalayas with a number of international agencies and published extensively on social sciences and development in Nepal and Asia.

Linda Stone, Ph.D, is Professor Emeritus of Anthropology at Washington State University in the United States. At the time of this study she was visiting Research Fellow at Centre for Nepal and Asian Studies, Tribhuvan University. Kathmandu. She has published a number of books and articles on Nepalese studies.

Ramesh Shrestha, M.A., was a lecturer of English at Department of English and researcher at Centre for Nepal and Asian Studies, Tribhuvan University at the time of this study. He's been living in Thailand since 1980 and currently spends his time in Bangkok and Kathmandu.

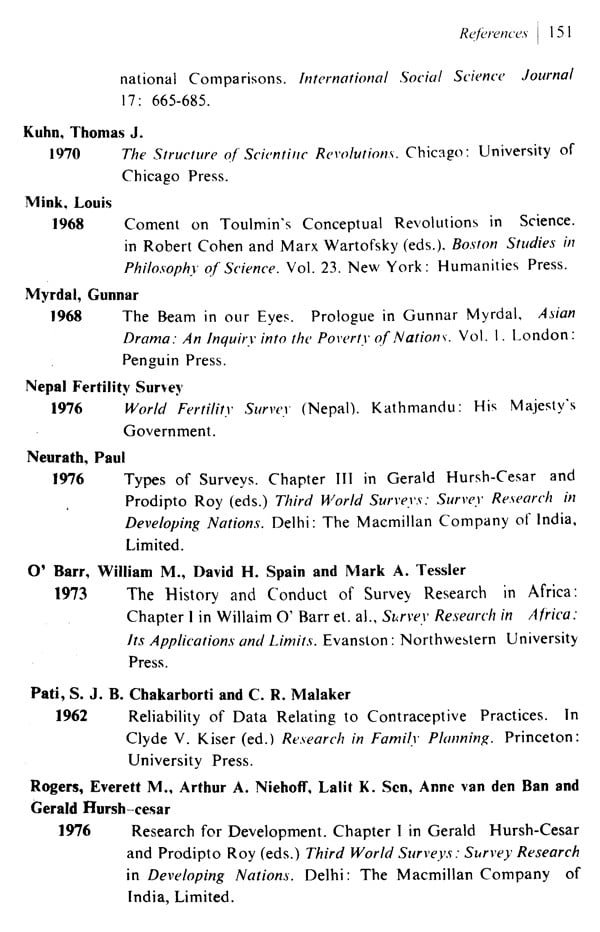

Foreword What use is a piece of survey research if a later crosscheck were to show that the data generated was highly unreliable? What if it happened that 15 percent and sometimes 25 percent or more of the households surveyed did not report information correctly? In addition, what if those households which gave wrong information did so at a significant to very large magnitude? In one crosscheck study of various surveys in Nepal, the answers provided on crop yield were wrong by as much as 184 percent and the answers on total grain sold were wrong by as much as 814 percent! Yes, there were domains- e.g. household composition, literacy, education, number of livestock owned, and women's fertility history in which the answers were far more reliable. Misreporting, on the other hand, was large in most 'economic sets of questions including those on crop yield, grain sold, grain exchanged in kind, annual income, etc. If this is the case, what implications can we draw about the epistemology and technology of survey research as such? And how can survey research be rescued, if at all, from producing information with a high degree of unreliability?

A second edition of this book, The Use and Misuse of Social Science Research in Nepal, which seeks to answer the important questions raised in the preceding paragraph, has long been overdue. The new edition, which is coming out after three long decades, comes in with new supplementary essays from the authors.

Preface The gap between what people say publically and privately, and between what people say and do, animates diplomats, politicians, marketers, development practitioners and social scientists. And yet, too often we continue to rely on surveys public, literary information gathering instruments administered by strangers-to guide our understanding of people's behavior and opinions. The mathematical beauty and ability to estimate error in sampling designs lull us into thinking the questionnaire answers are valid measures of what people think and do. The carefully crafted question in a linguistic form barely intelligible by most respondents makes us complacent towards the inevitable bias introduced by language and context.

The result, as this study demonstrated, is dangerously wrong and misleading information. As we further elaborated in our article in Human Organization, non-sampling error (lack of validity) was many times sampling error in most of the surveys tested. For example, in the test of Nepal Fertility Shady, our study found that 88% of Nepalese adult women had heard of family planning while the Nepal Fertility Study found only 22.4% having any knowledge of family planning. This test showed a maximum potential non sampling error of between 75%-95%.

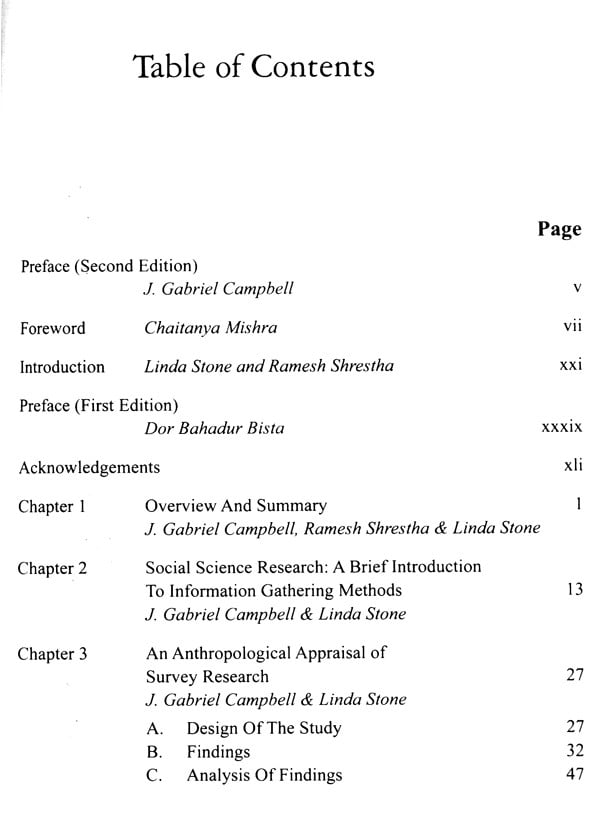

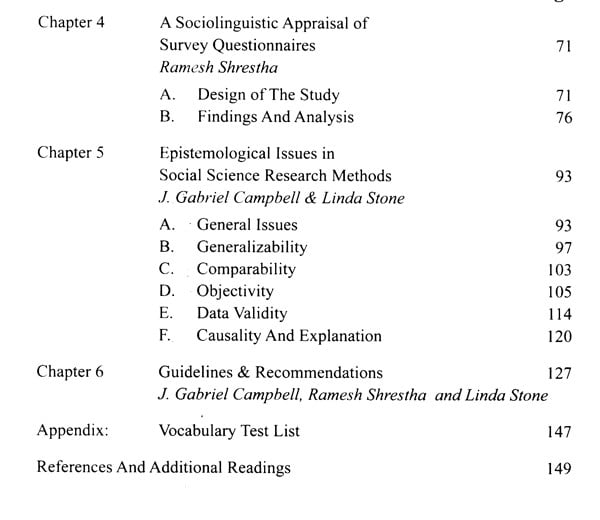

Introduction It has been over 30 years since the authors of this book undertook a novel social science research experiment in the country of Nepal. As described in Chapter One, our experiment was designed to test the validity of data obtained by survey questionnaires, widely administered by Nepal's development planners in rural areas of the country. In addition we tested the linguistic intelligibility of the questions used in these surveys among rural people. The authors, two cultural anthropologists and one linguist, had been for many years involved in ethnographic or linguistic research in the country and in development issues and projects. From our experiences we strongly suspected that these surveys were systematically generating inaccurate data. The results of our experiment that was designed to test this exceeded our own predictions: we found that surveys conducted throughout Nepal produced information especially concerning people's opinions, knowledge, and behavior that was incorrect and misleading, often widely off the mark.' In addition, many words, phrases, and questions in the survey instruments were not intelligible to significant numbers of rural people.

A great deal has changed since our experiment was undertaken and the results published in our 1979 book, The Use and Misuse of Social Science Research in Nepal.

**Contents and Sample Pages**