The Very Best of the Common Man (Best Cartoonist of India)

Book Specification

| Item Code: | NAF445 |

| Author: | R.K. Laxman |

| Publisher: | Penguin Books India Pvt. Ltd. |

| Language: | English |

| Edition: | 2012 |

| ISBN: | 9780143418719 |

| Pages: | 213 (Throughout B/W Illustrations) |

| Cover: | Paperback |

| Other Details | 8.0 Inch x 5.0 Inch |

| Weight | 160 gm |

Book Description

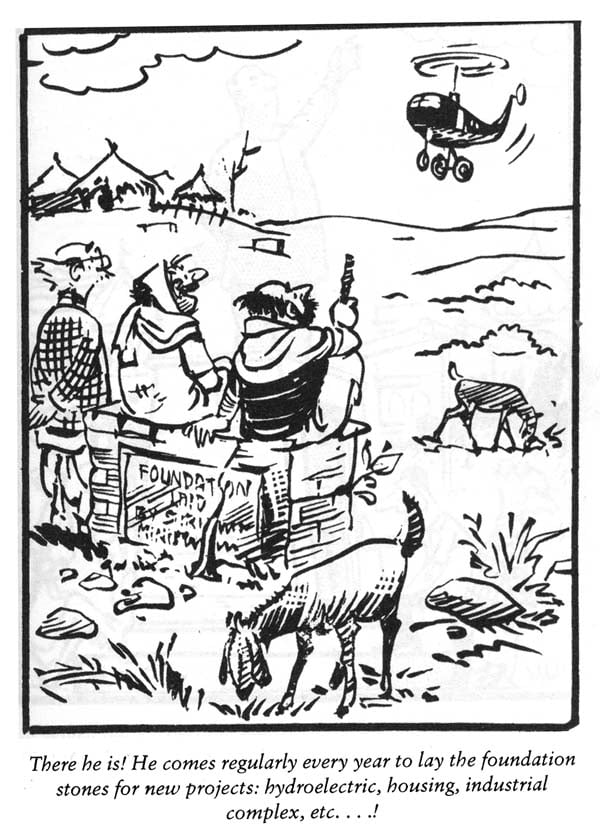

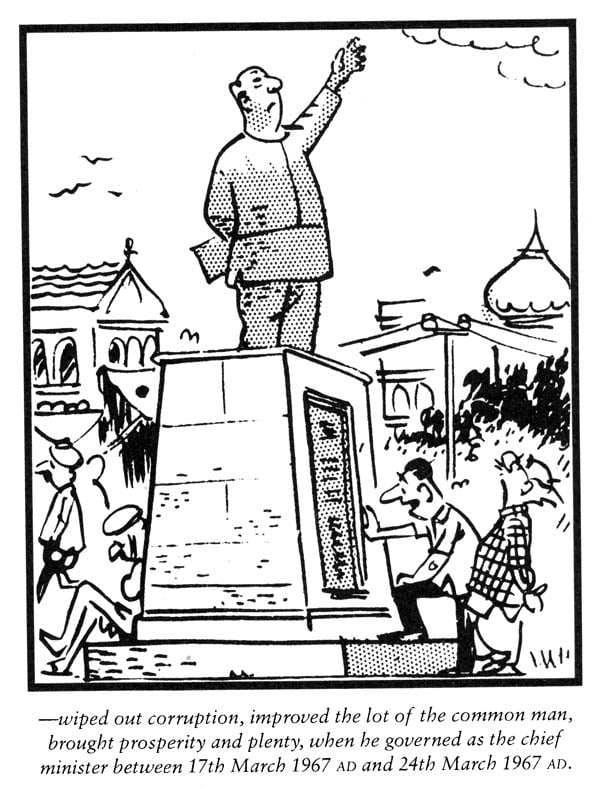

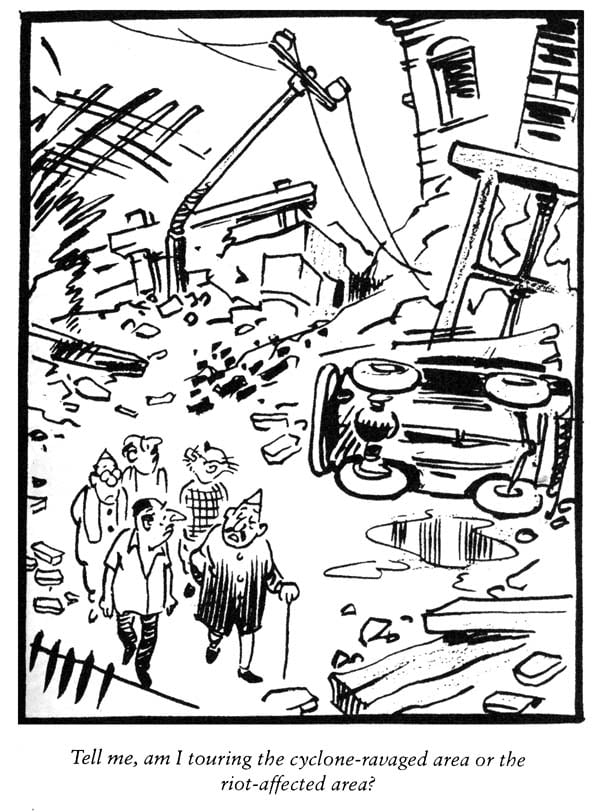

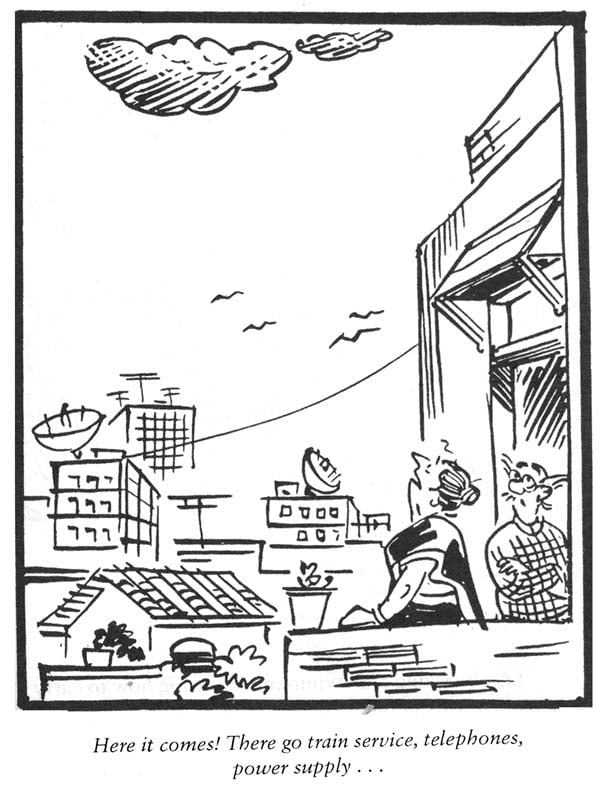

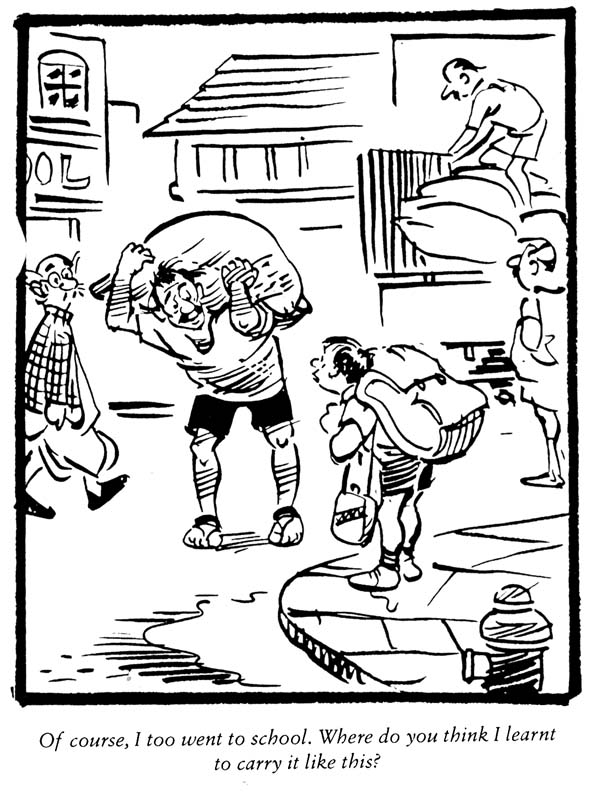

For half a century the Times of India has thoughtfully provided an antidote to all the bad news brimming on its front pages. It’s sketch, a single box, linked by R.K. Laxman, the country’s sharpest cartoonist and political satirist. Each morning, Laxman’s frazzled character, known as the Common Man, confronts India’s latest heartbreak with a kind of wry resignation. What’s common about this character is that like most Indians, he sees his country being forced through endless indignities by its leaders and yet doesn’t even whimper in protest,

From financial crises to the woes of householders from political instability to rampant corruption, Laxman’s Common Man cartoon capture the entire gamut of contemporary Indian experience. This special collection featuring the hundred most memorable Common Man cartoons of all time is a tribute to India’s best loved cartoonist and one of the most striking voices commenting on Indian sociopolitical life.

Just over a century ago the art of Cartooning came to Indian from England and struck roots. Although other forms of art like sculpture, poetry and painting had flourished in our country for centuries, the art of graphic satire and humour was unknown. Of course both satire and humorous did exist in folklore and popular poetry, poking fun at the follies of men and monarchs; the funny antics and humorous articles of the court jester were really satirical comments used to gently bring a wayward king and his band of countries back on track.

The role of today’s cartoonist is not unlike that of the court jester of yore. His business in a democracy is to exercise his right to criticize, ridicule, find fault with and demolish the establishment and political leaders, through cartoons and caricatures.

When the British ruled, the freedom allowed to the press was limited. The role of editorial comments and cartoons was largely confined to tackling social evils like child marriage, child labour and the dowry system, or praising the efforts of the reformers. They hardly ever touched on political subjects.

Some years later the Indian cartoonist began to make timid forays into political matters. But he confined himself to attacking symbols John Bull, for instance. When our struggle for independence from imperial domination began to gather momentum, the cartoonist gained the courage to depict real character the political leaders, and the viceroys and governors who were the guardians of imperial authority. Enslaved India was symbolized by an image of a suffering Indian woman called Bharat Mata a semi divine being adorning a crown with flowing black tresses wearing a carefully draped sari. The lady did indeed serve the purpose of inspiring patriotism in the heart of the people, inviting them to free themselves from the shackles of British imperialism.

When the British left, our leaders who had fought for independence, settled down to draw up a respectable constitution which would ensure freedom and equality for people who had been denied democratic liberty for centuries. India was declared a sovereign secular republic in which every citizen would enjoy liberty, equality and fraternity. The freedom of the press became particularly sacred. It was one of the most important checks to be imposed on our democratic institution. Having drowns up such a magnificent constitution, the leaders and the led sat themselves down and looked forward to a life of peace and prosperity.

If things had worked the way out founding fathers had hoped, the cartoonist would have become and extinct species long ago. But fortunately for the cartoonist, both the rulers and the ruled unintentionally became champions of the cartoonist of the cartoonist’s cause and ceaselessly provided grist to his mill.

When Nehru took over as prime minister, it soon forward became apparent to the cartoonist that he could look forward to an exciting career ahead. The aspirations of linguistic chauvinists, cow-protectors, prohibitionists, name changers of parks and streets all began to make their ludicrous appearance on the national scene. Our political activities became equally uproarious from the satirist’s point of view. Our leaders introduced an altogether new style of functioning in our political life hitherto unknown to the ordinary citizen. News about political parties did not concern their ideologies or their plans to help the common man, but detailed instead how intra party groups worked against each other, squabbled amongst themselves, parted company from the party to form a new one, or defected to the very party they had opposed tooth and mail until that very moment. All this led to curiouser and curiouser political behavior dharnas, floor-crossing, booth capturing, toppling a chef minster, and what have you. Naturally, a cartoonist even one with limited talent, could flourish effortlessly in this atmosphere. So, within a decade of independence the tribe of cartoonists proliferated. New dailies, weeklies and fortnightlies published in every feasible language mushroomed everywhere, thus opening up vast opportunities for the cartoonist.

As a nation we are rather prone to talk politics whether at a bus stand or in a railway compartment, hobnobbing at an exclusive cocktail party or jogging in a public part. Of course what passes for politics in these sessions is really gossip rumors, hearsay or scandal rooted in some blurred misrepresentation of facts concocted into a palatable mixture that is masticated between reading newspapers and magazines and listening to political news on the radio or television. That is why though not all Indian publications are political in content, most allow for a page or two of political satire and caricature, in acknowledgement of our national pastime. Thus the country that didn’t have a single cartoonist less than a century ago is now swarming with them good, bad and indifferent.

A I became more and more entrenched in watching and commenting on the political phantasmangoria or our country I needed an acceptable symbol to define the common Indian in my cartoonist has the Damocles, sward of deadlines hanging permanently over his head. Many precious minutes would be lost if I were to draw elaborate masses of people composed of Maharashtrians, Bengalies, Tamilians, Punjabis and Assamese. It is easy for the cartoonist in the west where the dress and appearance of people are largely standardized, but in India there is no way of classifying an individual by the dressed exactly like a retail fruit seller. Again, a scholar of Sanskrit, English, Greek and Latin might look like the humble priest of an old impoverished temple. How was I to discover and portray the common denomination in this medley of character, dresses, appearances and habits?

In the early days, I used to cram in as many figures as I could into a cartoon to represent the masses. Gradually I began to concentrate on fewer and fewer figures. These my readers came to accept as representative of the whole country. It would have been awfully anachronistic if I had attempted to prolong the presence of the Bharat Mata figure in my cartoons to symbolize the common people and their post independence turmoils. It would have been ridiculous, indeed, of Bharat Mata, with her crown and united hair, holding our national flag, was seen hanging around in the background at a cabinet meeting a glittering state banquet for a visiting foreign dignitary or at the airport watching worried minister dash off to Delhi. It would also not do to portray the common man in any manner one fancied, as many cartoonist did sometimes as an old man in rags, sometimes as an emaciated individual and so on, bearing the legend ‘The Common Man’ on the hem of his clothes.

Eventually, I succeeded in reducing my symbol to one man: a man in checked coat, whose bald head boats only a wisp of white hair and whose bristling moustache lends support to a bulbous nose, which in turn holds up an oversized pair of glasses. He has a permanent look of bewilderment of his face. He is ubiquitous. Today he is found hanging around a cabinet room where a high powered meeting is in progress. Tomorrow he is among the slum dwellers listening to their woes, or marching along with protestors as they demand the abolition of the nuclear bomb. That of course, does not preclude him from being present at a banquet hosted by the prime minster for a visiting foreign dignitary. This man has survived all sorts of domestic crises for forty years, long after the politicians who professed to protect him have disappeared. He is tough and durable. Like the mute millions of our country, he has not uttered a word in all the years he has been around. He is silent, bewildered and often bemused spectator of events which anyway are beyond his control.

Besides my usual big cartoons, I started a series called you said it. A single column cartoon appeared every day in the Times of India, in the right hand corner of the front page. The idea was to make it a free wheeling comment on socio economics and sociopolitical aspects, free of real political personalities or actual political events. The feature did not attempt any serious analyisis but reflected, with a certain conscious irreverence, the general mood of the country as whole. I expected this column to appeal to readers who were not too critical and who accepted their humdrum lot without a murmur. My taciturn common man, who was appearing off and on in my bigger cartoons in the company of Nehru and his cabinet ministers, came in handy for this purpose. The other characters I built around him in this purpose. The other characters I built around him in this single column cartoon were villagers, bureaucrats, ministers, crooked businessmen, economic experts, rebellious students, factory workers in fact nearly every type, from every walk of life as the occasion warranted. The column proved to be extremely popular. It has appeared every day for more than half a century, except on those all too brief occasions when I am on holiday.

Gathered in this volume is a selection from the cartoons I have done over the last few years. I am continually surprised to note that most of them are timeless in their relevance to any given moment in our history.