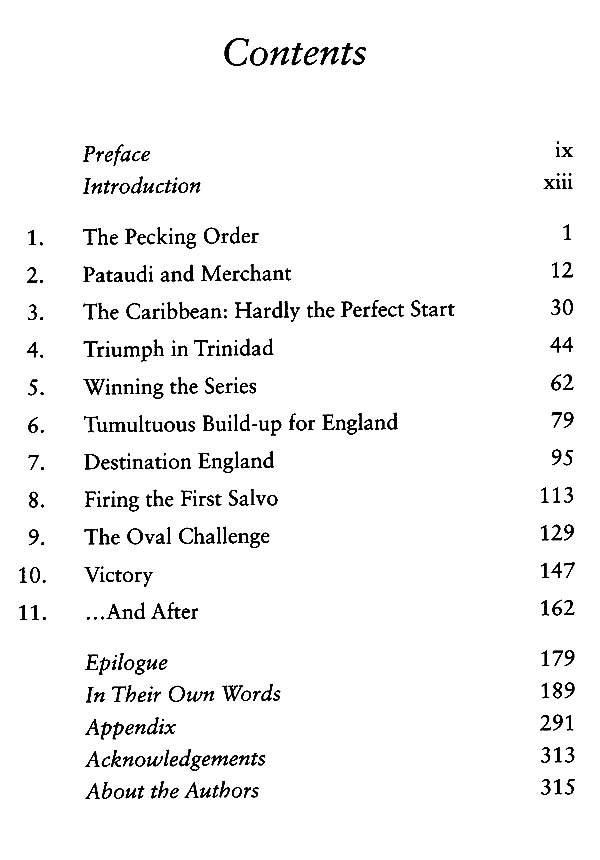

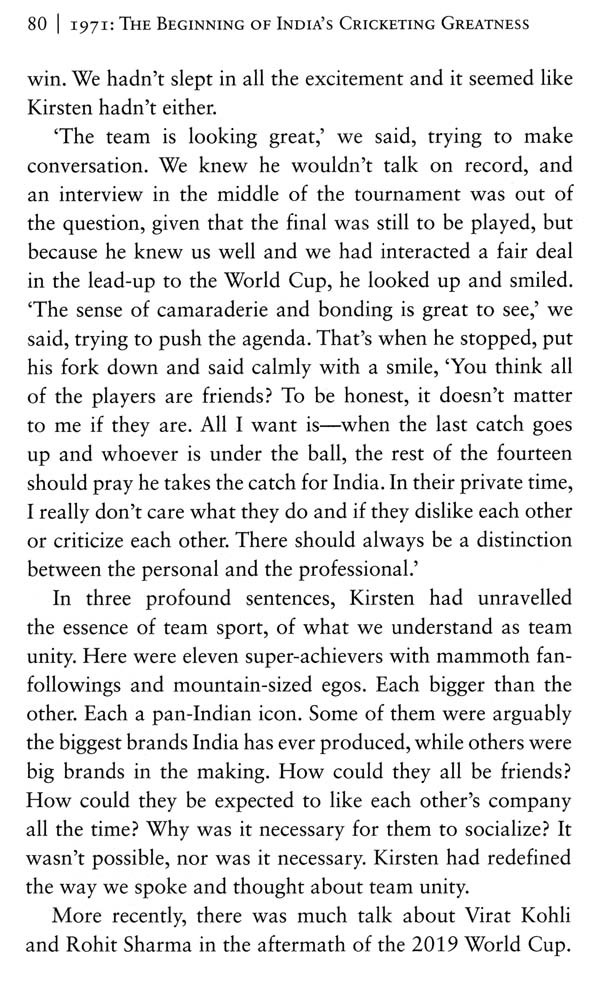

1971- The Beginning of India's Cricketing Greatness

Book Specification

| Item Code: | NBZ111 |

| Author: | Boria Majumdar and Gautam Bhattacharya |

| Publisher: | Harper Collins Publishers |

| Language: | ENGLISH |

| Edition: | 2021 |

| ISBN: | 9789354223068 |

| Pages: | 315 (37 B/W Illustrations) |

| Cover: | PAPERBACK |

| Other Details | 8.50 X 5.50 inch |

| Weight | 330 gm |

Book Description

1971 was the year that changed Indian cricket forever. Accustomed to seeing a talented but erratic Indian team go from one defeat to another, a stunned cricketing world watched in astonishment as India first beat the West Indies in a Test series on their home turf, and then emerged victorious over England-in England. Suddenly, the Indian team had become a force to reckon with.

Boria Majumdar and Gautam Bhattacharya's book is a thrilling account of the 1971 twin tours, that brings to life the on-field excitement and the backroom drama. Against a canvas that features legends: Pataudi and Wadekar, who captained India to the two sensational series victories abroad; Sardesai, Durani, Viswanath, Engineer, Solkar, Abid Ali; the famed spin quartet of Bedi, Prasanna, Chandrasekhar and Venkataraghavan; and a young batsman named Sunil Gavaskar who was making his debut-it is the tale of a young country ready and eager to make an impression on the world stage.

Fifty years later, this is a wonderful book to relive those glory days with.

BORIA MAJUMDAR, a Rhodes Scholar, is the author of multiple books on Indian sport and its history, and the co-author of Sachin Tendulkar's autobiography Playing It My Way. His most recent publications include Eleven Gods and a Billion Indians (2018) and Dreams of a Billion: India and the Olympic Games (with Nalin Mehta, 2020). He is Senior Research Fellow at the University of Central Lancashire and Consulting Editor, Sports, for the India Today Group. @BoriaMajumdar FB, Twitter, Insta

GAUTAM BHATTACHARYA, currently the Joint Editor of Kolkata's leading daily Sangbad Pratidin, has been a long-standing cricket writer and commentator, and is the author of several books. In a career spanning four decades, apart from cricket reporting from across the globe, he has had the rare privilege of interviewing some of the all-time greats of the game. He is the co-author of Sourav Ganguly's book A Century Is Not Enough.

Thank God there was 1971. 2020 was perhaps the worst year in centuries, with stress and anxiety levels reaching new heights in India due to the COVID-19 pandemic. The coronavirus caseload in the country is in crores now-lakhs of people have lost their lives, and the situation is still far from normal. Besides COVID-19, there are several other issues the country faces. We saw the worst of the media in the Sushant Singh Rajput case, and it challenged the very idea of the unified India that we stand for. In Delhi, the political rhetoric is perhaps the worst it has been in a while. Communal tensions have been on the rise, and scepticism about the economy and its continual slowdown has raged unabated. Amid all this negativity, sports and, more importantly, this book have been a source of sustenance for us both.

Life and sports as we knew them before 2020 have changed drastically. The International Cricket Council (ICC) Women's T20 World Cup final between hosts Australia and first-time finalists India saw a record 86,174-strong crowd on 8 March. Towards the close of the year, Naomi Osaka, the young Japanese tennis star, stood in solidarity with victims of systemic racial discrimination by wearing masks at the US Open with the names of the victims on them. Poland's Iga Swiatek won her country's first Grand Slam singles title as she became the youngest women's champion at the French Open since 1992. Young leaders from sports emerged elsewhere, too. Para-badminton world champion Manasi Joshi, one of Time magazine's 'Next Generation Leaders', became the first Indian para-athlete to have a doll modelled to her likeness as part of the Barbie `Sheroes' family. The shift in narrative around female athletes continued while the emergence of bio-bubbles in the wake of the coronavirus pandemic marked a new era in the practice and organization of sports worldwide. We witnessed Board of Control for Cricket in India (BCCI) President Sourav Ganguly do his best to stage the Indian Premier League (IPL) in the UAE and badminton guru Pullela Gopichand work tirelessly during the months-long lockdown to spread the message of physical literacy in India. Amid all these victories against seemingly insurmountable odds, the essence of 1971 came to the fore - the perfect underdog story that ended in triumph. A story of hope, resilience and ecstasy. And with the fiftieth anniversary of the twin tours of 1971 upon us, we wanted to document the stories of that memorable year. So here we are with our labour of love-a work of cricket literature that helped us get through COVID-19 and allowed us to retain some semblance of normalcy during the lockdown, making us believe that not all is lost yet.

In the last major cricket event of 2020, the Women's T20 World Cup, sixteen-year-old Shafali Varma, who once had to dress up as a boy to get an opportunity to play among the kids in her state, Haryana, donned India colours and lived her dream. In the IPL, we witnessed many more like her do the same. Teen batsman and 2020 Under-19 World Cup star performer Yashaswi Jaiswal, for example, bought by the Rajasthan Royals for 2.4 crore, is the next big thing in Indian cricket. Devdutt Padikkal, who in his debut IPL season showed immense character when batting with Virat Kohli for the Royal Challengers Bangalore, is as promising. Sports, in these times of despair, remains a ray of hope. It brings with it an optimism that inspires confidence in the idea of India we stand for and believe in, and remains a true mirror of our democracy. And each of the men and women mentioned above carry a history that is a testament to the greatness India can achieve in the years to come. That's what makes 1971 relevant. Padikkal and Jaiswal are very similar to Sunil Gavaskar. Had there been no Gavaskar, one wonders if the likes of Padikkal and Jaiswal would have pursued the sport. The year 1971 was the foundation on which the present superstructure of Indian cricket was built. It allowed us to believe in Gavaskar's sacrifices and successes, and even inspired Sachin Tendulkar to play the game. And that we can produce a Tendulkar, whose family was anything but rich, underlines something inherently good about India. As Tendulkar once said, 'Very rarely does the whole country unite on something. That's what sports is able to do.'

At a time when the idea of India is being challenged at every step and politics has become all about personal slander, animosity and violence, the 1971 story comes as a breath of fresh air. And that's why we hope you will welcome this book. We cannot escape the reality that is primetime television news in India; as a society, though, we can already see signs that suggest it could do more harm to the fabric of our democracy than good. As the idea of the real India continues to be mutilated in the fight for television ratings, stories about the victories achieved by the Indian men's cricket team in 1971 can make a difference. At least we believe they can. In 1971, did the people of India care about the religion or economic background of the cricketers who made up the national team? Perhaps not. Instead, each time Gavaskar scored a century, all of India collectively celebrated his and the team's feats. Political parties across the spectrum enjoyed the success of Ajit Wadekar and his boys, and corporate India, most likely for the first time, came together to applaud the new champions. The national rhetoric, despite the backdrop of the war over Bangladesh, was one of achievement and success about what India could do rather than what was wrong with the country. And to read and recreate this story for all of you when our sensibilities were being challenged every day was a huge relief. To us, this is more than just a book. This project helped us move on with life and gave us reasons to believe that a relook at our history could help us envision a better future for India.

Never before had India won a Test match against the West Indies. And in what was a fateful tour to the Caribbean in 1962, India almost lost its captain, Nari Contractor, forever to a vicious Charlie Griffith bouncer. While Contractor survived the threat, his cricket career was over. Shaken by the incident, a 0-5 defeat against the likes of Wes Hall and Charlie Griffith wasn't a surprise. With new captain Mansoor Ali Khan Pataudi forced to take charge and no one wanting to open the batting in the aftermath of what had happened to Contractor, the tour ended up being a poor misadventure for the Indian team. Given the reputation of lethal fast bowlers operating on surfaces conducive to pace with no limit on the number of bouncers coupled with the, relentless earfuls doled out by the hostile crowds, touring the West Indies was considered the ultimate test for a cricketer in the 1960s and 1970s. While it is true that the 1971 team that faced India did not have fast bowlers of the quality of Hall and Griffith, it was still a West Indies team led by Sir Garfield Sobers, and included batsmen like Clive Lloyd, Rohan Kanhai, Roy Fredericks and Sobers himself. To even suggest that it was a series win of modest significance is to miss the point altogether.

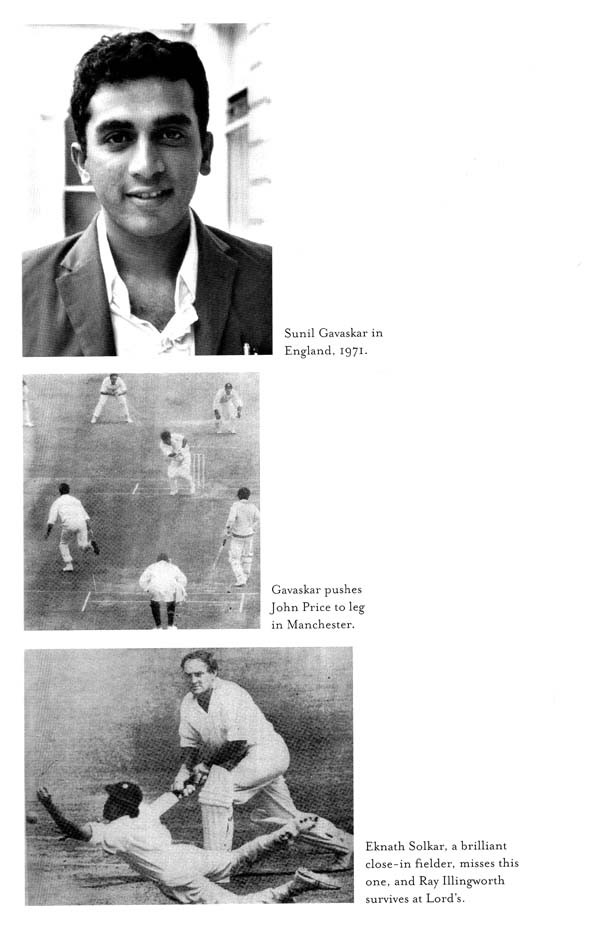

To the Indians, it did not matter. For them, what really mattered was the series win. The embarrassment of 1962 had been avenged and they had taken giant strides in establishing themselves as an evolving power in world cricket. Sunil Gavaskar was hailed the world over as a new phenomenon and captain Ajit Wadekar's support for Dilip Sardesai stood vindicated. Sardesai, who had made it to the team because of Wadekar's confidence in his abilities, played the best he ever had in his career.

That this victory had struck a chord with fans back home was evident when thousands turned up at the Santacruz airport in Bombay (as Mumbai was known at the time) to welcome the players back. This was also a sign of things to come-television had not yet become a mass medium of communication in India, and all the fans had to rely on was radio commentary and newspaper reports that were a day old because of the time difference.

There was, however, a section that remained unimpressed. The West Indies, it was argued, was no England, and Wadekar's real test would come two months later when the Indians toured the UK. England, fresh off an Ashes victory under Ray Illingworth and a come-from-behind victory against Pakistan, was widely accepted as the best team in the world at the time, and most did not give the Indians a chance. India's poor away record in England-lost 0-5 in 1958 and 0-3 in 1967-was repeatedly cited in the media to keep a lid on people's expectations. A drawn series, it was felt, was as good as a win in English conditions. Former India players, while praising the team for winning the away series in the West Indies for the very first time, were also wary of India's chances in England. In the absence of a good crop of fast bowlers and a stable middle order, India was always going to struggle against the likes of John Snow, Derek Underwood, Geoffrey Boycott and Ray Illingworth.

While the Indians missed out at Lord's and got a tad lucky in Manchester because of the rain, it all boiled down to the third and final Test match at The Oval in London. With a record of fifteen defeats in nineteen Tests at the ground going into the match, Wadekar's team needed something extraordinary to happen to change their poor track record at The Oval. This was more so after England managed a 71-run first-innings lead and appeared to be in firm control of the contest. With two days still left to play, India's breakthrough summer was gradually starting to get out of control.

And then, it became the Bhagwat Chandrasekhar show.

To Wadekar's credit, he attacked from the outset in England's second innings. The deficit of 71 runs wasn't something that had influenced his tactics, and the aggression fetched him immediate dividends, with England, reduced to 24 for 3 against the guile of Chandrasekhar. Chandra had picked 2 in 2 off the last 2 balls before lunch in five minutes of intense drama.

**Contents and Sample Pages**