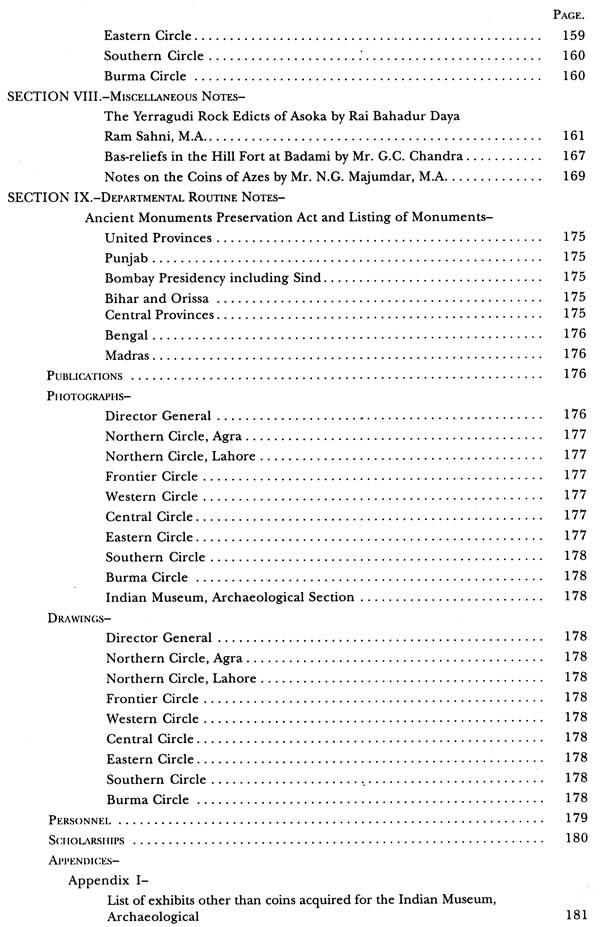

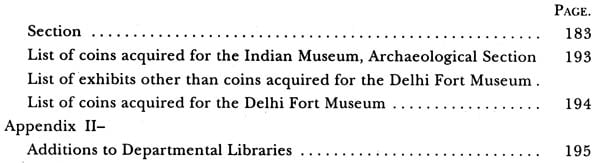

Annual Report of Archaeological Survey of India (1928-29)

Book Specification

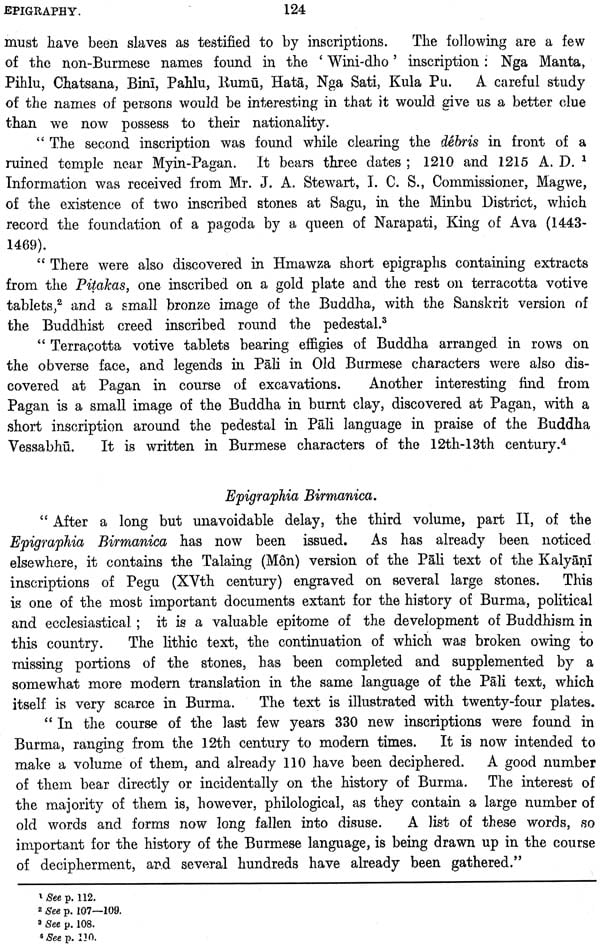

| Item Code: | NAW449 |

| Author: | H. Hargreaves |

| Publisher: | ARCHAEOLOGICAL SURVEY OF INDIA |

| Language: | English |

| Edition: | 2002 |

| Pages: | 276 (64 b/w Illustrations) |

| Cover: | HARDCOVER |

| Other Details | 11.00 X 9.00 inch |

| Weight | 1.63 kg |

Book Description

In all the varied activities of the Archeological Survey, conservation, exploration, research and epigraphy, the year 1928-29 has been one of steady progress.

A recently compiled consolidated list of monuments protected under the Ancient Monuments Preservation Act reveals that no less than three thousand one hundred and seventy are maintained by the Central Government alone. They include ancient sites, baths, bridges, caves, forts, gardens, gateways, In- scribed rocks, images, serais, kos minars, mosques, monasteries, palaces, pillars, pagodas, tombs, tanks, towers, temples, wells and the walls of ruined and desert- ed forts and cities as well as some four hundred miscellaneous objects and build- ings. As a result of the measures taken by the Archeological Department over a period of twenty-eight years the number of monuments calling for special repairs of a striking nature diminishes and conservation tends, therefore, to become more routine and limited to annual repairs and maintenance, both very necessary and calling for skilled, intelligent and constant supervision, but works in no way spectacular and but rarely lending themselves to a detailed description likely to make a strong general appeal. Nevertheless the paramount importance of the standing monuments cannot be contested and hence in this report priority is given to that section of the activities of the Department on which is expended the greater part of the archeological funds and of the energies of its oificers.

The departmental execution of the conservation of central protected monuments, already adopted in the United Provinces and discussed in the introductory paragraphs of the Reports for the years 1923-24 and 1925-26, has been extended this year to the Punjab, where all the archeological monuments, Muhammadan and British as well as Hindu and Buddhist, have been placed under the direct control of the Superintendent, Frontier Circle, who is now responsible for their upkeep, repair and maintenance. The pumping plant at certain monuments has, however, been allowed to remain under the local Public Works Department, their working requiring special mechanical knowledge. The extra responsibilities thus devolved upon the Superintendent, Frontier Circle, necessitated a corresponding increase in his establishment, and additional staff has been sanctioned. to assist him in the discharge of his additional duties. To enable him to exercise closer supervision over conservation works, his headquarters have, for the time being, been transferred from Peshawar to Lahore, a subsidiary office being retained at Peshawar, where his Personal Assistant has been stationed for the maintenance of the monuments in the North West Frontier Province. Although this was the first year that conservation in the Punjab was carried out departmentally, no special difficulties were experienced though the conservation programme was exceptionally heavy.

Excavations have been carried out at no less than eleven sites. At Taxila with the completion of the ‘‘ Palace’ excavation and the clearance of several blocks of houses on the east side of the Main Street operations in the Scytho-Parthian city of Sirkap have, for the time being, been brought to a conclusion and work directed to the opening up of the earlier strata of remains below. As the spade goes deeper, the area that can be excavated for a given sum necessarily grows less and less and it is not to be expected, therefore, that the excavation of the lower cities will yield as rich a harvest of antiquities as the Scytho-Parthian city has done. Nevertheless, to judge by what has already been achieved, there in every prospect that the excavators will succeed in pushing back the story of this civilisation for several more centuries.

Continued excavation of the prehistoric sites of Harappa and Mohenjodaro yielded for the most part structural remains and antiquities resembling those found in former years. The most significant find reported from Harappa is that of seven burial jars and eight skeletons, seeming indications of a cemetery of chalcolithic times. The anthropological importance of the remains likely to be recovered from its exploration is such that Mr. Vats’ further investigations in this particular direction will be awaited with interest.

At Mohenjodaro Mr. Mackay has cleared a portion of what he considers to be the " Artizan’s Quarter’’ of the Late Period, but the principal operation was the excavation of a large area to a depth of some twenty-three feet below the original surface of the mound and to the fourth level of occupation. In this fourth stratum it is now possible to walk through the streets and to enter many of the buildings of the period as easily as did its original inhabitants. A steady deterioration of the masonry and the decreasing size of the houses appears to be an index of the decay of this civilization from the Early to the Late Period. A similar deterioration is noted at Harappa.

The discovery of evidence of flooding between the Early and Intermediate Periods at Mohenjodaro indicates the former existence of a danger to which Mohenjodaro even to-day is still exposed. Mr. Mackay is of opinion that a recently discovered cylinder seal shows that the upper strata of Mohenjodaro can be safely dated to 3000-2750 B.C. as its form is very like pre-Sargonic seals found in Mesopotamia. As, however, the seal in question 1s acknowledged to be Indian in origin it appears somewhat temerarious to base so wide a conclusion on a single object.

Seals recovered at Mohenjodaro showing a goddess in a pipal tree and another horned figure in yoga attitude (which has been identified with Siva) and a seal from Harappa depicting a deity standing under a pipal tree and an- other seal displaying a rosette of seven pipal leaves are not without significance and tend to give a stronger Indian than western orientation to this Indus Valley culture. It is not therefore improbable that at these sites may later be recover- ed definite prototypes of Indian deities and traces of art motifs and cults which persist to ‘the present day.

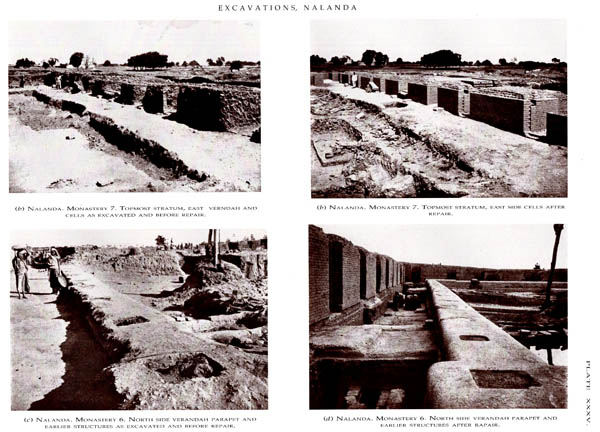

Explorations at Nalanda were largely confined to the Monastery Sites. To the vicissitudes experienced by these monasteries the clear traces of frequent destruction bear ample witness. The antiquities recovered were principally Buddhist images and articles of domestic use. Conservation of the excavated remains has proceeded pari passu with their exploration, and an endeavour has been made by Mr. Page to exhibit a definite portion of each of the several structures which have been erected on the ruins of others throughout: the long occupation of the site.

Mon. Duroiselle’s researches in Burma were confined to two sites, Hmawza and Pagan, At the former site thirty-two mounds were explored revealing the remains of stupa and burial mounds and yielding bronze and small gold images, and votive tablets of the 5th and 10th centuries.

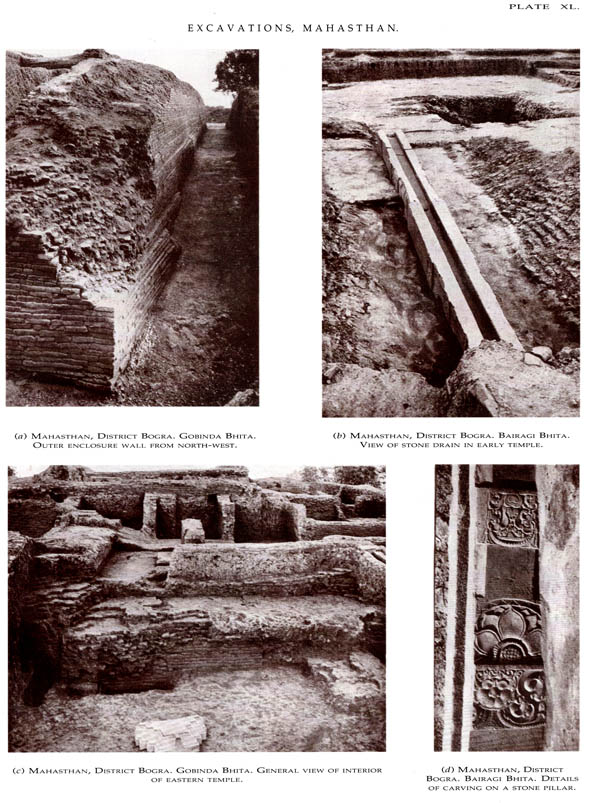

In Bengal Mr. Dikshit carried out researches at Mahasthan, Paharpur and Rangamati. Mahasthan in the Bogra District and the largest known ancient site in Bengal is, in the Karatoyd-Mahatmya, identified with Paundranagara. From the excavations it appears that the city site was in occupation from early Gupta times, and that after the Gupta period the city decayed but was reoccupied in the Pala period, the excavated city wall and bastion being assignable to that occupation. The identification of the site with Paundranagara still awaits confirmation, but a more detailed examination of the Gupta levels may afford this. Further exploration at Paharpur was confined almost entirely to the examination of fifteen cells of the monastery while the trial excavation at Rangamati on the west bank of the Bhagirathi, six miles below Berhampore; despite the disturbance of the site by treasure seekers and brick robbers, disclosed three periods of occupation, the earliest yielding Buddhist remains of the 6-7th centuries.

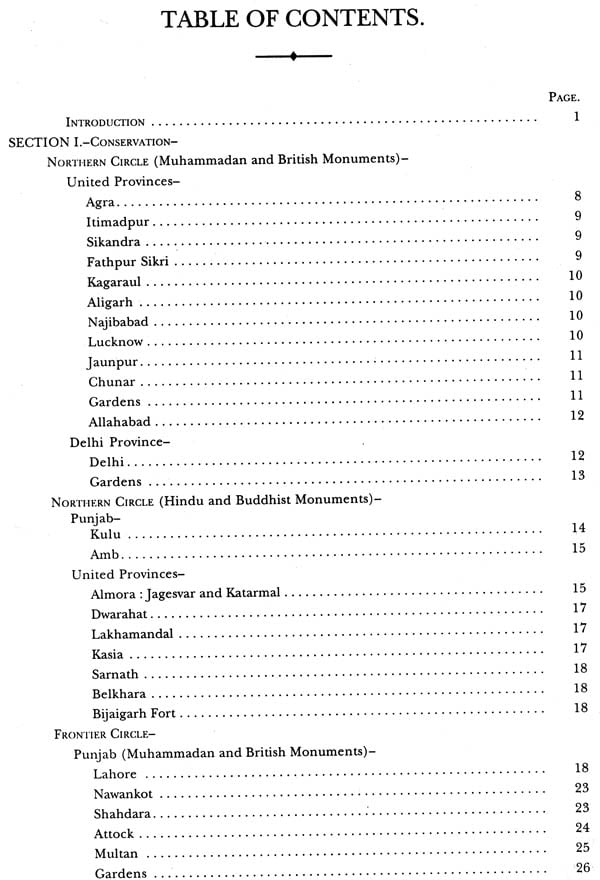

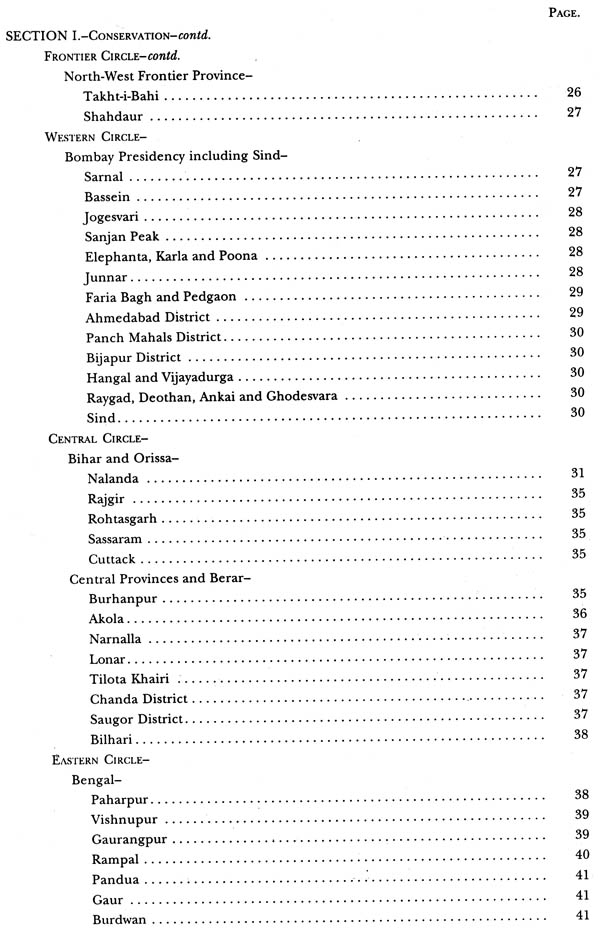

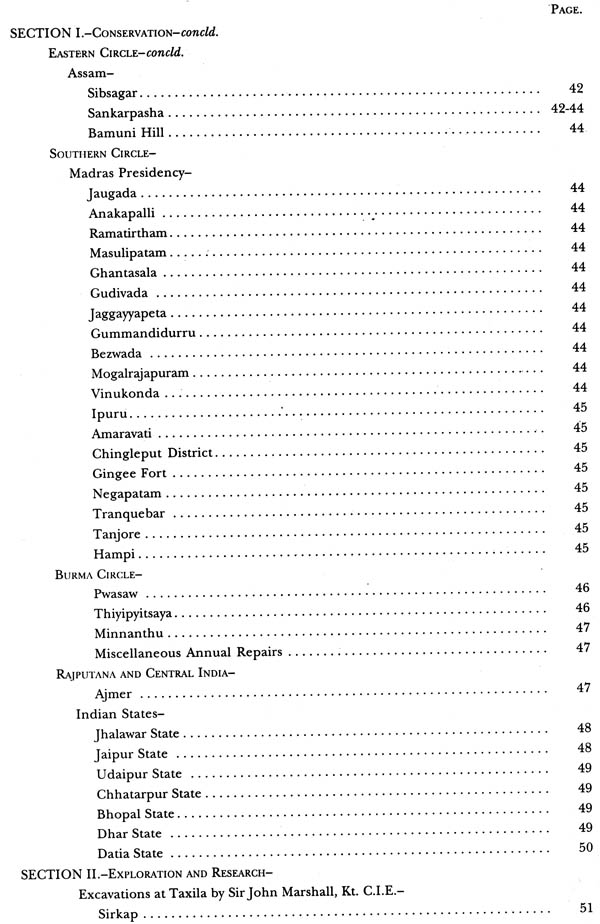

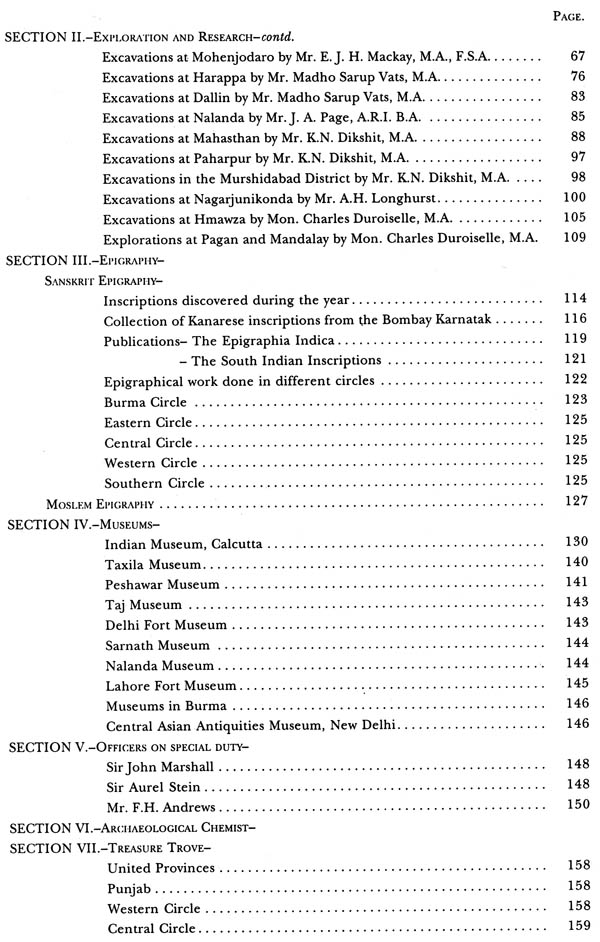

**Contents and Sample Pages**