An Anthology of Writings on the Ganga (Goddess and River in History, Culture, and Society)

Book Specification

| Item Code: | NAK648 |

| Author: | Assa Doron |

| Publisher: | Oxford University Press, New Delhi |

| Language: | English |

| Edition: | 2015 |

| ISBN: | 9780198089643 |

| Pages: | 374 |

| Cover: | Hardcover |

| Other Details | 8.5 inch x 5.5 inch |

| Weight | 540 gm |

Book Description

Back of the Book

According to the epic Ramayana. King Bhagiratha believed that the goddess Ganga could bring salvation to his ancestors who had been cursed by a seer. As a result of his religious austerities she descended from Heaven to Earth, with the journey mediated by Lord Shiva, who subdued Ganga's tempestuous flow through his matted locks. To this day, for the Hindus in India the Ganga remains more than a river-she is the epitome of all sacred waters and the quintessential symbol of India.

To other Indians and to foreign travellers for hundreds of years the Ganga has been the spine of India. conveying goods, people and ideas across thousands of kilometres and nurturing one of the world's most fertile agricultural systems.

About the Book

The quintessential symbol of India, the epitome of all sacred waters, a mother goddess, and an essential lifeline sustaining the livelihoods of millions-the Ganga is India's most revered river. This anthology presents a selection of writings that reflects the ways the Ganga has been encountered through the centuries-as a liberating force, a source of wonder and inspiration, a means of transport and centre of trade, a geographical curiosity, and a habitat for a wide variety of animals and plants.

This collection explores the length of the river, from its source to its delta, bringing together various perspectives from the mythical, material, and spiritual dimensions. It includes founding myths from the epics Ramayana and Mahabharata, excerpts from translations of the classic Padma Nadir Majhi and the screenplay of Ram Teri Ganga Maili, accounts of travellers from Tavernier to Newby, Nehru's 'Will and Testament', and selections from Amitav Ghosh, Vik ram Seth, and Raja Rao. The anthology will serve as essential reading 101' those seeking to understand the significance of the river in Indian civilization and wanting to engage with exciting debates about the 'modern' and 'traditional', the 'epic' and the 'everyday'.

About the Author

Assa Doron teaches at the Department of Anthropology. College of Asia and the Pacific. The Australian National University. Canberra.

Introduction

The Ganga or, as it is also known, the Ganges-along with the Nile, the Tigris and Euphrates, the Yangize and the Danube-is one of the great rivers of our planet. Each of these rivers serves not just as a provider of water, bearer of goods, and definer of borders but as an archetypical nourishing mother of human civilization. While all of these rivers are mothers figuratively or symbolically, only the Ganga is Ganga Ma, Mother Ganga, in the most literal possible sense for hundreds of millions of Hindus. This puts the Ganga in a league of its own and makes of it an alluring subject for writing of all genres-from the historical, geographical, and ecological through the cultural, religious, and anthropological to the poetic, mystical, and philosophical. Equally alluring for us has been the challenge of compiling this anthology of writings on the River Ganga. We have selected samples from this range of genres since the seventeenth century, focusing mostly on the past 200 years.

Beginning this anthology with mythological accounts of Gangas descent to earth is essential if we are to appreciate some of the ideas, concepts, and practices that have excited generations of writers across various disciplines and persuasions. One way to orient ourselves in our journey along the Ganga is to engage a tour guide. In fact, we envision two guides, as it were, who might shed light on our path and choices for compiling this anthology: the Hindu philosopher and reformer Vallabha (1478-1530) and Vyasa, the traditional compiler of the Mahabharata.

Our first guide, Vallabha, has been our inspiration for including articles on the basis of their authors' manner of perceiving the Ganga. In verses 5 to 6 of his Siddhantamuktduali, Vallabha explains that there are three degrees of perception through which one may regard the Ganga: firstly as a stream of material water, secondly as a stream of material water with the spiritual capability to remove sin, and thirdly as a sin-removing stream of water that is the manifestation of the divine Ganga Ma.

The authors of some of our selections, notably Eric Newby in 'The Way to Mirzapur' from his Slowly Down the Ganges and Manik Bandopadhyaya in a chapter from his Bengali novel Padma River Boatman, present the Ganga through Vallabha's first degree of perception. For them the river is an elemental force: fecund and full of beauty but dangerous and impossible to predict.

In other selections we find authors who look at the Ganga with Vallabha's second degree of perception as a source of spiritual cleansing and redemption. For some of these authors this spiritual perception is framed in terms that are religious. For example, in the Hindi story The Drowsiness of Chait Dulls the Spirit' by Shiv Prasad Mishra, who often writes under the pen-name Rudra Kashikey, Pundit Padmanand finds redemption (moksha) in the Ganga at the end of his life as 'he struggled to drink a few handfuls of water'. In a more ironic portrayal of religion, Ilija Trojanow in 'The Sage's Wet Hair' describes an Indian Oil signboard at Haridwar which advises pilgrims: 'Whoever sings the aarti daily-switch off engine at a signal and save 20% petrol-shall achieve moksha effortlessly'. Other selections are by authors who are not religious but nevertheless find spiritual purification in the Ganga. One of these is that most avowedly secular of Indians Jawaharlal Nehru who, in his 'Will and Testament', was moved to write that 'The Ganga, especially, is the river of India, beloved of her people, round which are intertwined her racial memories, her hopes and fears, her songs of triumph, her victories, and her defeats.' Vijay Singh is another author who in his highly personal narrative 'Gangotri' describes how, with a bottle of rum in his hand, he experienced an epiphany involving his beloved, his mother, and the Ganga all in one.

In a third group of our selections, the authors are solidly in the realm of the goddess Ganga. Among these is the anonymous folk poet who cries out in anguish, in Shakuntala Varma's translation, 'O Ganga give me a big wave so that I drown in it' and Diana L. Eck who pays scholarly homage to the Ganga in her 'Ganga: The Goddess Ganges in Hindu Sacred Geography'. The apparent gulf between the unquestioning devotion of the folk poet and the sophisticated gaze of the anthropologist is bridged by the validity of the desire for the divine in the human heart that both accept.

Of course, in relatively few of our selections is only one of Vallabha's degrees of perception of the Ganga present. After all, the whole point of Vallabha's conception is that the third degree of perception comprises the first and second and the second contains the first. The way that the three degrees of perception fir into each other is especially well illustrated by the various myths of the origin of the Ganga found in the ancient Ramayana and Mahabharata texts, translated by Robert P. Goldman and J.A.B. van Buitenen respectively, and in modern guise in the legends told in the excerpt from Vikram Seths novel A Suitable Boy. In the same vein are the efforts of Amitav Ghosh's geologist in 'Beginning Again' from his novel, The Hungry Tide, to link the material perspective of natural science with the transcendent Ganga by asking his students 'What do our old myths have in common with geology?' and answering his own question with the words 'Goddesses, children ... Don't you see: goddesses are what they have in common.' Finally, there is the contrast of the uncompromisingly material geographic approach to the Ganga found in the excerpt from James Fraser's Account of a Journey to the Sources of the Jumna and Bhagirathi Rivers' with the spiritual and divine geography of the Ganga of Hindu poets discussed by Richard Barz in 'Gangotri, Gomukh and the Sources of the Ganga'.

This interweaving of the various realms of social life-economic, cultural, and spiritual-are illustrated by Doron's study of the river economy of Banaras (Varanasi), where boatmen lay claim to the prestigious title, Sons of the Ganga, often to the chagrin of their upper-caste counterparts. Such claims have spiritual and ritual significance, as well as political and economic ramifications, for the everyday lives of marginalized groups and their struggle for self-assertion.

While Vallabha's material, spiritual, and divine degrees of perception provided a productive set of criteria for choosing the selections for this anthology, they are much too pervasive in the collection to be useful for organization. For purposes of organization we have followed Vyasa's cue in the way in which his Mahabharata embraces the numinous and the historical together with accounts of famous places, outright fiction, and scholarship.

We begin the anthology with the numinous, providing from the Ramayana and the Mahabharata accounts of how Ganga Ma descended from the heavens to offer salvation on earth. Although these narratives are coherent in spirit, they are by no means mutually consistent in fact. The Ramayana explains how Ganga Ma came to plunge from her course across the night sky as the Milky Way, with her fall broken and channelled through the tangled locks of the god Shiva, in order to glide to earth bringing liberation to humanity as the mother river of India. The Mahabharata portrays the Ganga as the source of the divine power of life, nourishing and purifying on the one hand and destructive on the other.

Since the numen of the Ganga is not limited to the Ganga alone but extends in greater or lesser degree to all the waters of India, we have included Anne Feldhaus's 'The Descent of the Ganga' and A.K. Ramanujan's translation of the Kannada poem 'A Pond Named Ganga' by Chandrashekhar Kambar. In the former, a tale from the Gautami Mahatmya is related in which the Godavari River is Revealed to be the southern branch of the Ganga and, in the latter, even a village pool is a manifestation of Ganga Ma.

Contents

| Acknowledgements | ix |

| Introduction | xi |

| THE EPIC AND NUMINOUS | |

| The Descent of the Ganga | |

| The Ramayana of Valmiki | 3 |

| The Mahabharara | 17 |

| The Descent of the Ganga | 16 |

| Poems and a Will | |

| Prayer to Mother Goddess 1 | 30 |

| Prayer to Mother Goddess 4 | 32 |

| Sohar 10 | 34 |

| Sohar 11 | 36 |

| A Pond Named Ganga | 38 |

| Will and Testament | 42 |

| HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVES | |

| Travels in India | 47 |

| India in the Early 19th Century: An Iranian's Travel Account, Translated of Mir’at ul- ahwal-i-jahan numa | 55 |

| Account of a Journey to the Sources of the Jumna and Bhagirathi Rivers | 61 |

| Letter to a Friend | 70 |

| On the Ganges | 79 |

| CONTEMPORARY TRAVEL WRITING | |

| The Way to Mirzapur | 87 |

| A Long Time on the Ganga | 100 |

| Gangotri | 109 |

| The Sage's Wet Hair | 117 |

| Sunrise on the Ganga | 122 |

| FICTION | |

| Padma River Boatman | 135 |

| Ram Teri Ganga Maili | 146 |

| On the Ganga Ghat | 151 |

| The Rainbow | 159 |

| A Suitable Boy | 168 |

| Beginning Again | 186 |

| The Drowsiness of Chait Dulls the Spirit | 190 |

| RECENT SCHOLARSHIP | |

| The Bengal Steam Department's Hindus and Muslims | 199 |

| The Ganges in Bengal | 218 |

| Ganga: The Goddess Ganges in Hindu Sacred Geography | 233 |

| Why Sink Flowers? Bringing It All Back Home | 252 |

| Separate Domains: Hinduism, Politics, and Environmental Pollution | 272 |

| Gangotri, Gomukh and the Sources of the Ganga | 302 |

| Hello Boat! The River Economy in Banaras | 325 |

| Copyright Statement | 341 |

| Glossary | 344 |

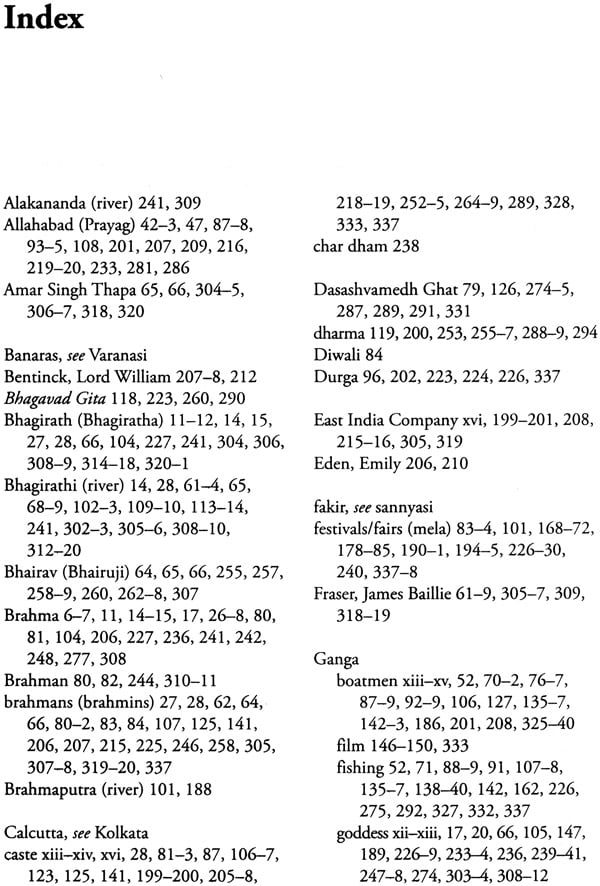

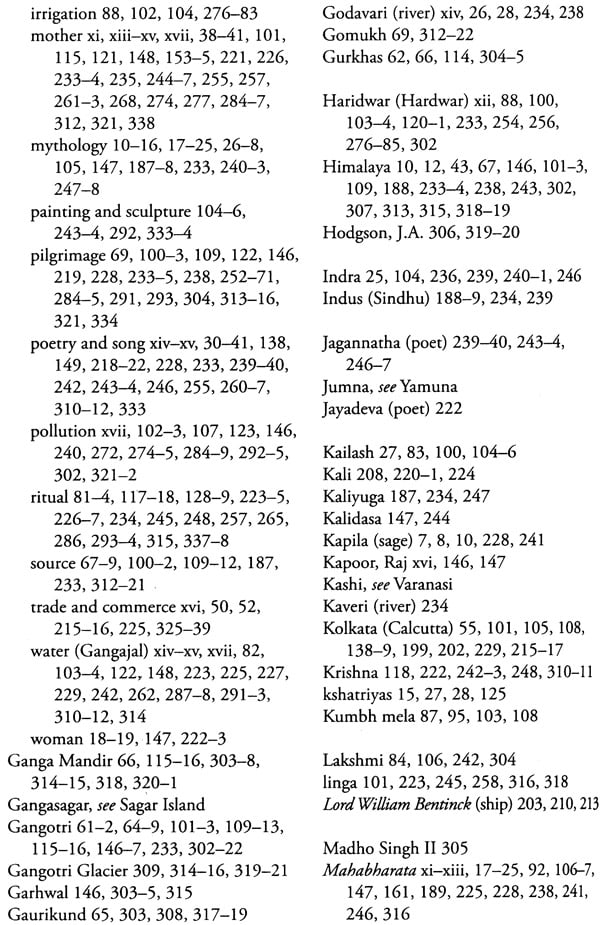

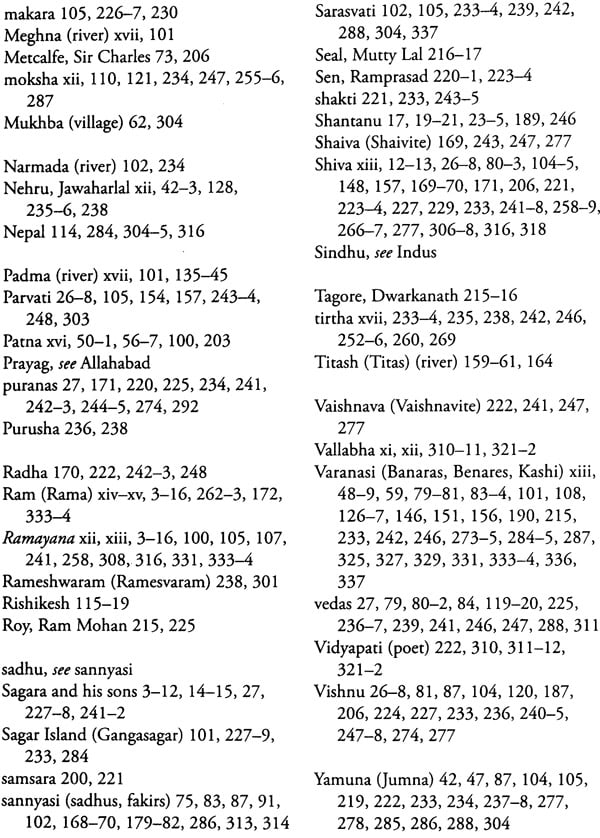

| Index | 347 |

| About the Editors and Contributors | 350 |