Healing at The Borderland of Medicine and Religion

Book Specification

| Item Code: | NAJ307 |

| Author: | Michael H. Cohen |

| Publisher: | Orient Longman Pvt. Ltd. |

| Language: | English |

| Edition: | 2007 |

| ISBN: | 9788125032298 |

| Pages: | 250 |

| Cover: | Paperback |

| Other Details | 8.5 inch X 5.5 inch |

| Weight | 280 gm |

Book Description

About the Book

One of the transformations facing health care in the twenty-first century is the safe, effective, and appropriate integration of conventional, or biomedical, care with complementary and alternative medical (CAM) therapies, such as acupuncture, chiropractic, massage therapy, herbal medicine, and spiritual healing. In Healing at the Borderland of Medicine and Religion, Michael H. Cohen discusses the need for establishing rules and standards to facilitate appropriate integration of conventional and CAM therapies.

The kind of integrated health care many patients seek dwells in a borderland between the physical and the spiritual, between the quantifiable and the immeasurable, Cohen observes. But this mix of care fails to present clear rules for clinicians regarding which therapies to recommend, accept, or discourage, and how to discuss patient requests regarding inclusion of such therapies. Focusing on the social, intellectual, and spiritual dimensions of integrative care and grounding his analysis in the attendant legal, regulatory, and institutional changes, Cohen provides a multidisciplinary examination of the shift to a more fluid, pluralistic health care environment.

About the Author

Michael H. Cohen holds a joint appointment as assistant clinical professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School and assistant professor in the Department of Health Policy and Management at Harvard School of Public Health. I le is also senior lecturer at the University of the Bahamas, president of the Institute for Integrative and Energy Medicine, and principal in the Law Offices of Michael H. Cohen. He is author of five books, including Complementary and Alternative Medicine: Legal Boundaries and Regulatory Perspectives.

Introduction

At the First International Congress on Tibetan Medicine in Washington, D.C., the Dalai Lama reminded the audience that the first, international congress on Tibetan medicine was actually held in the seventh or eight century, not the twentieth. Furthermore, the congress was held in Tibet, not in the American capital, and finally, the historical conclave focused on the shared medical traditions of India, Nepal, China, Persia, and Tibet, traditions that already reflected an ethic of medical pluralism.' The Dalai Lama went on to point out that even at that meeting-long before the notion of “complementary therapies” had become popular in the United States-Tibetan medical culture already represented an amalgamation of influences from other traditions, and it already manifested deep respect for international collaboration and shared research efforts.

With gentle hum or, in his keynote address the Dalai Lama reflected on the hubris and ethnocentrism often described as embedded in modern scientific efforts within the Western Hemisphere to understand indigenous and other medical traditions. The medical stance implicitly critiqued by the Dalai Lama has been described by some critics as one of “co-optation” and assimilation, rather than true collaboration between camps. In other words, even when open to exploring other medical systems, clinicians and research scientists adhering too rigidly to the Western, scientific model-that is, without fully appreciating the asserted role of consciousness in mediating healing therapies-tend to imagine that the medical system adopted relatively recently in human history, in part of the globe, authoritatively can filter, understand, and synthesize other medical traditions.

The Dalai Lama's assertion that this approach may suffer from hubris does not deny the power and elegance of the scientific method to probe questions of safety, efficacy, and mechanism. No doubt scientific inquiry represents a powerful method for discerning truth in discovery. Scientific study to date has invalidated a number of would-be cures outside conventional medicine (such as laetrile for cancer) and validated others (such as acupuncture to control nausea following chemotherapy).

But science is not the whole of authority, and the Dalai Lama was not criticizing the power of medicine and science but, rather, the exclusive claim these disciplines hold on our epistemological framework-on what we hold to be true, real, and valid. Balanced against scientific method are other modes of inquiry, from other disciplines in the humanities and from within human experience.

The lineage within which the Dalai Lama sits represents one of the great contributions to human understanding of the realms of mind and spirit-a technology of consciousness, if you will. His implicit critique of biomedical ethnocentrism suggests a need to balance current scientific inquiry, on one hand, and tolerance and respect for foreign theories and systems of health care, on the other. His challenge is in essence about embracing pluralism: momentarily suspending categorical disbelief, and being willing to try to understand some of the methods in these nonbiomedical healing systems (such as the mysterious “pulse diagnosis” in Tibetan medicine) on their own terms. Those terms of reference may include framing healing as a transfer of consciousness, healing intention, or therapeutic information through the medium of “spiritual energy” -for lack of better terminology-that is, through as yet unknown mechanisms. Contrary to reductionistic attempts to boil all inner awakening down to biochemical processes (a posture William lames termed “medical materialism”),” an opening to pluralism refuses to dismiss phenomena that may not yet be validated under generally accepted frameworks in one cultural frame of reference, as “implausible” and therefore invalid.”

In other words, the Dalai Lama's challenge-and the parallel objective of this book-is to navigate or negotiate the bridge between these seemingly opposite parts of the world of healing. Some parts are objective, while others are entirely subjective. Some are externalized; others, deeply within. Some are comprehensible according to commonly agreed standards, but others are incomprehensible or inaccessible to generally accepted rules of evidence. Some operate according to known rules, and others are touted by believers, on one hand, as authoritative and dismissed by skeptics, on the other, as irrational and hallucinatory.

This navigational task is freighted with contradictions. For example, the catchphrase “mind-body” (as in mind-body medicine, one of the terms bandied about in moving beyond conventional or “orthodox” medicine) itself embodies (so to speak) deep contradictions, a presumptive crossing of chasms that may be unbridgeable if rhetoric alone purports to mediate understanding. A subtle aspect of the challenge in bridging these disparate arenas is to include tools from both worlds (e.g., science and religion, physics and metaphysics, concrete and consciousness). Hence the emphasis in this book is on “negotiating” the new health care-a task of harmonizing where possible, integrating where appropriate, and synthesizing where beneficial. The negotiation at the borderland of healing and medicine is not only between M.D. and patient but also between M.D.'s, D.O.'s, allied health providers, and practitioners of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM). The negotiation between West and East, biomedicine and CAM-whatever metaphor one chooses- affects all health care professionals (and patients and those who study and those who regulate these dynamics), not only physicians. The multifaceted negotiation includes negotiating different world- views, epistemologies, hermeneutics, and metaphors for health and healing.

During the Tibetan medicine conference, the contrast between Western, scientific medicine (or biomedicine) and Tibetan medicine was visually demonstrated in the difference between many of the speakers (in starched shirts, knotted ties, and expensive haircuts) and the monks (with their saffron robes and shaved heads); between the disposable conference brochures formatted on high-speed laser printers and the Kalachakra (Wheel of Time) mandala, with its pristine colors and precise figurines of deities, painted in colored sands according to ancient Tibetan prescription; between the preoccupation with position, status, academic affiliation, or salary (or dependency on communication gadgets) and the ceremonial gesture of sweeping away the beautiful mandala at the conference's conclusion -a ritualistic meditation on impermanence.

The contrast reminded me of a meeting about five years earlier, when I was an associate at Davis Polk & Wardwell, a Wall Street law firm. The theme of negotiating bridges between worlds was present even then, metaphorically and literally. I was negotiating a copyright agreement between a Tibetan cultural foundation, our pro bono client, and a group of monks that the foundation had brought to the West to share knowledge of the Kalachakra sand painting.

My client and I met with the monks and their lawyer in a room about twenty feet behind the New York stage on which the Dalai Lama was giving a talk. I recall greeting the monks individually, meeting their steady gaze, and noticing the head-bows and the hands folded in Namaste or prayer position. While negotiating the agreement's terms with their representative, I had the sense that these monks were sending blessings our way: their silence was profoundly full. In a fleeting way-without being distracted from my role as a lawyer-I could almost feel the ghosts, deities, and subtle levels of consciousness that Tibetan teachings describe, as we sat, within the energy field of the Dalai Lama, unseen and yet present, trying to reach consensus.

At the Tibetan medicine conference, political and medical landscapes had shifted since that earlier negotiation. The monks and their mandala were not new to the West; the agreement had long been concluded, and many books about their spiritual healing traditions had been published. CAM therapies, such as (in order of most commonly licensed providers) chiropractic, acupuncture and traditional oriental medicine, massage therapy, and naturopathic medicine figured on biomedical, regulatory, and political maps. Some of the leading medical schools were offering courses on CAM therapies, while others had invited Tibetan physicians to participate in research studies. I had moved from Wall Street to legal academe to explore legal, reguiatory, ethical, and policy questions at the intersection of conventional and complementary medicine.

At the conference, my role involved not a hardheaded, softhearted negotiation between client and monks but, instead, the task of leading a panel, composed of Tibetan medicine practitioners and representatives from various nations, on licensure, liability, and other legal considerations involved in bringing Tibetan medicine to the United States. The old dichotomies seemed to have melted into a world in which ancient and modern had to find mechanisms for peaceful coexistence and even mutual respect and accommodation.

During the conference, I had the opportunity to meet one of the senior physicians to the Dalai Lama and to experience his mind, consciousness, and knowledge of Tibetan medicine. My encounter with him was mysterious, sublime, and portending of things below the surface of conversation. Yet, by biomedical standards, this subjective impression might be dismissed as anecdotal, ungrounded, or-using the often applied label for a beneficial effect whose only basis is the “good medicine” of relationship-placebo. Again, the contrast between my felt sense of the encounter and how it might be analyzed from a contemporary biomedical perspective reminded me that, although the conference aimed to explore scientific analysis of the Tibetan arts, in many ways the two worlds remained apart, and polarities persisted. Scientists and religious leaders were engaged in dialogue and in the attempt to find common language, yet many “truths” the religious leaders took for granted could not possibly be tested or validated scientifically. The fundamental epistemological assumptions of each camp and the starting premises of each for inquiry were startlingly dissimilar.

Contents

| Acknowledgments | xi |

| Introduction | 1 |

| CHAPTER 1 |

|

| Negotiating the New Health Care | 19 |

| CHAPTER 2 |

|

| Regulating Health Care Rogues | 49 |

| CHAPTER 3 |

|

| Regulation, Religious Experience, and Epilepsy | 65 |

| CHAPTER 4 |

|

| Healing, Environment, and Ecology | 73 |

| CHAPTER 5 |

|

| Renewing the Matrix of Health and Healing | 99 |

| CHAPTER 6 |

|

| Healing at the Borderland of Medicine and Religion | 111 |

| EPILOGUE |

|

| Toward the Future | 153 |

| APPENDIX A |

|

| State of the Evidence Regarding Complementary Therapies | 163 |

| APPENDIX B |

|

| Key Arenas of Legal and Policy Intervention | 165 |

| Notes | 169 |

| Bibliography | 211 |

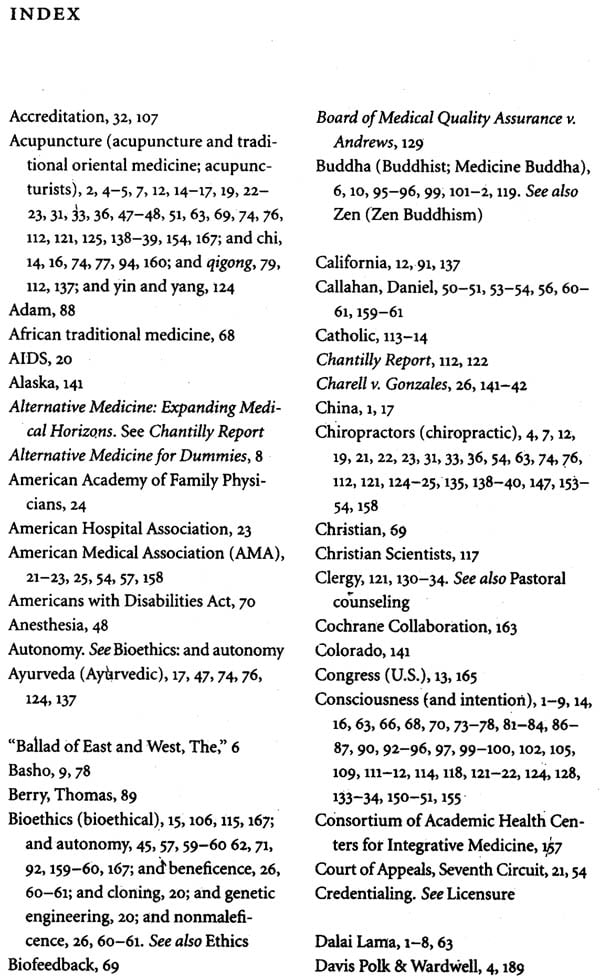

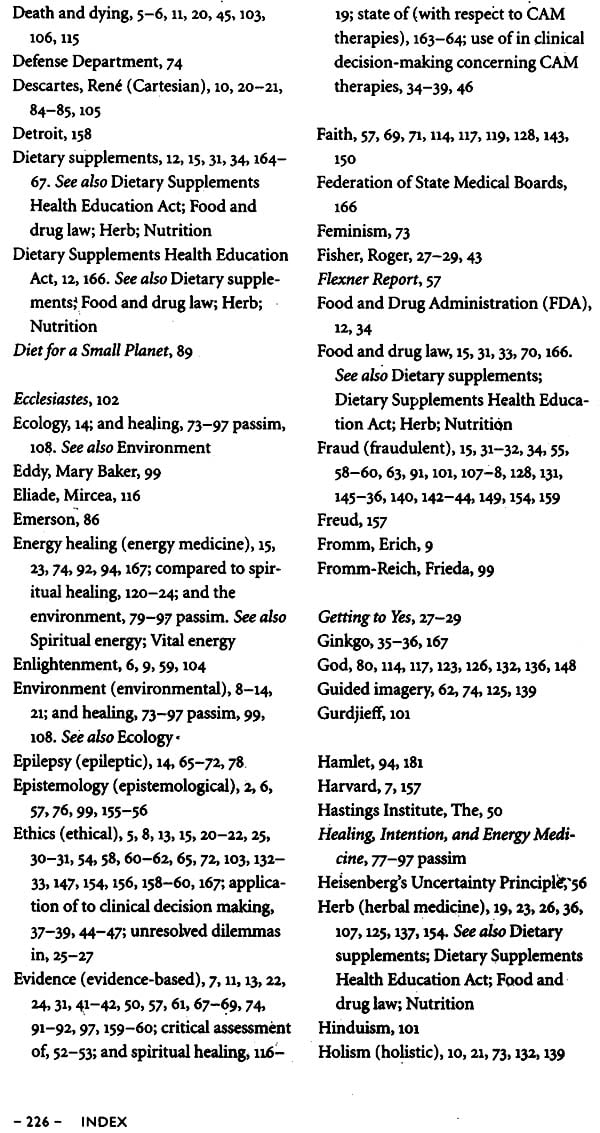

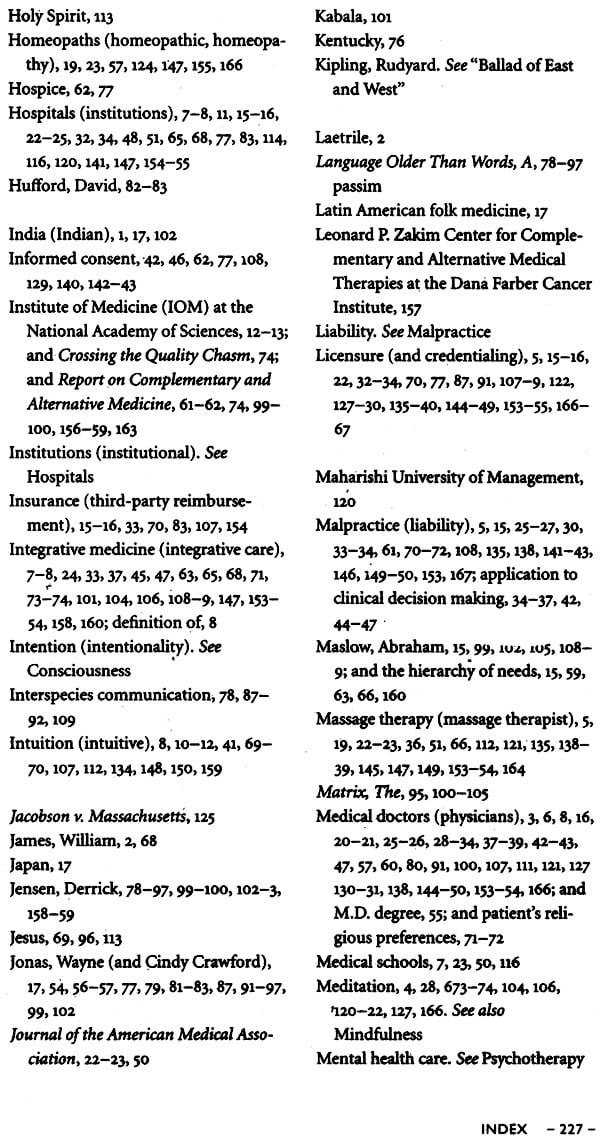

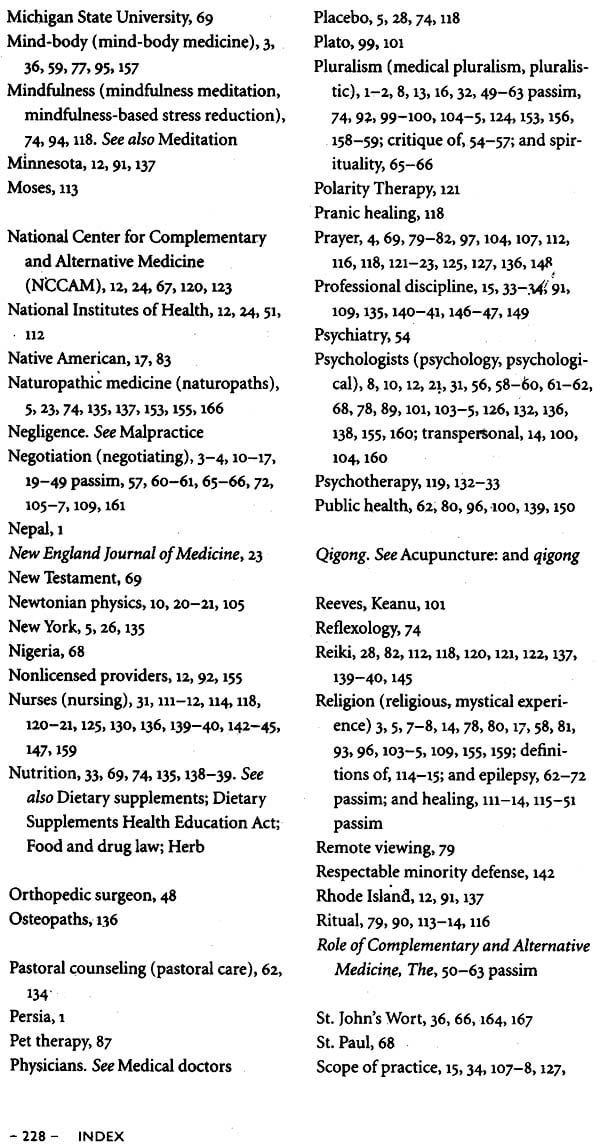

| Index | 225 |