Katha - Yoga: Yadantah Tadupaasitavyam (Which is Inside, That is to be Meditated Upon)

Book Specification

| Item Code: | NAF424 |

| Author: | Dr. Sivananda Murty |

| Publisher: | Aditya Prakashan |

| Language: | English |

| Edition: | 2009 |

| ISBN: | 9788177420913 |

| Pages: | 154 |

| Cover: | Paperback |

| Other Details | 8.5 inch X 5.5 inch |

Book Description

About the Book

Kathopanishad is one of the most important of the ten major Upanishads that are usually commented upon by noted scholars as constituting the cream of Upanishadic philosophy. All schools of Vedantic philosophy Advaita, Dvaita, and Visishthadvaita have chosen these ten with a particular attention given to the Katha. Shri Adishankara has commented upon the Kathopanishad in an advaitic manner, propounding its ultimate truth to be the unqualified non-dual Brahman. Such an explanation, however, does not teach any practice or sadhana that leads to this experience only, but an intellectual understanding. Yet this Upanishad narrates an unprecedented event:a Brahmin boy goes to the realm of Lord Yama, the God of death, and seeks instruction from him about what happens to human beings after death. The story reflects certain yoga experiences, the travel of the youth to the realm of the God of death and his eventual return to his father on earth. All this involves a yogic miracle which has not been focused on by any commentary so far. It reflects certain yogic practices for facing death and moving beyond its grip.

The author Dr. Sivananda Murty targets this particular event, analyzing the yogic feat of a person leaving his body without death and coming back into three days later. Dr. Sevananda Murty clearly explains the yogic practices involved in the process, perhaps for the first time. This interpretation therefore has a unique place among the commentaries on the Upanishad. Yoga is a great science of sciences and has its own unrivalled place among all philosophies as it leads one to a direct experience of the ultimate truth. Dr. Sivananda Murty explains the secret Yoga of the Kathopanishad, not meraly its philosophy. As the katha is also traditionally regarded as a Yoga Shastra, his views help us understand why this might be the case. The original Telugu and English commentaries are the author’s own. A Hindi translation has also appeared in recent years.

About the Author

Dr. Kandukuri Sivananda Murty, D. Litt (b.1928, Andhra Pradesh) is a multifaceted personality – an embodiment of Sanatana Dharma, a fountain of Vedic learning, a positive interpreter of Puranic-lore, a complete Yogi, a blend of Vedic od art and letters, a music lover, a cultural interpreter to the West, an observing traveller to the East and the West, a performer of Vedic rituals in all corners of India for the welfare of the people, culture and country, a devout patriot, a philanthropist, an inspirer, an unswerving social activist, preceptor, educator, philosopher, a homoeopath, a keen reader and a prolific writer. Above all, He is a Divine father, a caretaker, a saviour, a well-wisher and a spiritual guide to thousands of His devotees spread over the globe who are treated as His extended family. He is highly respected by the most learned scholars of our country. His works include Sivarnabhumi, Kathayoga, Bharateeyata (2 volumes), Maharshula Charitra (2 volumes), Gautama Buddha, besides innumerable incisive articles published in the dailies and periodicals over several decades. His spiritual path is Yoga, humanist patriotism, way of life. He loves and appreciates honest patriots across religion and politics.

Preface

It is six years since the first English version of my commentary was published. Dr. Frawley, the erudite scholar, author of many books on Astrology, and many Vedic subjects, has paid his attention to this. Another equally important contribution to this work is that of Mahamahopadhyaya, Prof. Sri Pullela Sriramachandrudu, who is one of the outstanding scholars we have in India today. A person with many excellent works on Vedanta, Darsanas and Sanskrit literature to his credit, he has enriched the Indian literature in an unprecedented manner and scale. It is my food fortune that he has made a critical study of my work both in its Telugu version and the English rendering presented here. He has given his learned opinion on this English version. I consider his opinion an authentication of this work of mine.

My valued friend and an eminent orientalist and author, Dr. Frawley has edited, rearranged and improved the clarity of the text with great care, making it readable to wider circles of readership. I cannot adequately thank him for his great contribution. The repetition of some ideas in the commentary could not be avoided due to demand of the context. I crave the reader’s indulgence for such repetition. I consider it a great advantage that this work has received in the editing by Dr. Frawley.

After what I have received from Dr. Frawley and Dr. Sriramachandrudu, I have nothing more to ask for. It is the spiritual truth- content in this work that has to find a genuine readership and acceptance. The delay and any inadequacies are my own.

Foreword

The Upanishads have formed the prernnial fountainhead of Indian spirituality since well before the time of the Buddha. They have continued on throughout the centuries as the most enduring and dynamic portion of india’s great Vedic heritage that goes bac to the very dawn of human history. The Upanishasds have inspired the innumerable great seers and yogis of the region and provided them with the basis for their numerous profound teachings and practices. The Upanishads present the prime Vedantic doctrines of Atman and Brahman, Karma, rebirth and liberation as well outlining as the prime Yogic methods of mantra and meditation that have long characterized this great spiritual tradition and which were adopted by later Buddhist and Jain teachings as well.

Yet there remains much ignorance about the Upanishads and their message and some mystery about their meaning. In the western world, the Upanishads are treated either as books of inspirational thoughts or as seeds of later rational philosophical systems, but they are rarely examind in thier own right. They are regarded as the oldest texts of Indian philosophy, showing how it arose out of a Vedic ritualistic background, but there is little understanding of their Vedic basis and their deep connection with the mysterious Vedic Mantras.

The Upanishads are seldom looked upon as living teachings or of practical relevance for the spiritual life of people today in the modern world. Though Yoga is popular in the West, it is mainly the asana (postures) side that is followed and the Upanishadic basis of Yoga, though emphasized by many great Yogis from India, is seldom appreciated. Few Yoga teachers, much less students, have any real knowledge of these foundational texts of the very tradition that they may claim to be part of.

In India, the Upanishads are regarded as ancient scriptures and no doubt highly honoured, but seldom studied in a serious manner as manuals of Yoga and meditation. They are usually looked upon as the source books for later philosophies of Advaita or Dvaita. Their commentaries have long assumed more importance than the actual texts, which few look directly into or care for in themselves. People are inclined to debate these rather long and abstruse commentaries, which often get caught up in secondary details, rather than to meditate upon the original texts and try to directly ascertain their meaning.

It can be argued that the Upanishads are the most important texts o fall Indian teachings of all systems. They formed not only the foundation on which later Vedantic philosophy was built and the system of Yoga arose; they are also a mysterious door back into the Vedic world with its cryptic Mantras and luminous symbols that appeal more to an intuitive mind rather than to the logical intellect. In the Upanishads, both the Vedantic philosophy of the Atman and the Vadic symbology of fire and light coexist as one integral teaching that can communicate simultaneously to both the rational and intuitive aspects of our consciousness.

The Katha Upanishad

The Katha is perhaps the most interesting of the several shorter classical Upanishads. It is much easier to understand than older, longer and more Vedic Upanishads like the Chandogya and Brihadaranyaka, which reflect a more archaic Vedic language and symbolism. Yet the Katha has its own aura of mystery and still reflects many older Vedic ideas and practices.

Yama, the God of Death, is the main teacher or guru of this Upanishad, who instructs the youth Nachiketa. Death is often the great teacher in spiritual teachings throughout the world. Death is arguably our original teacher as it compels us to look more deeply into the meaning of our lives. On an inner level, God himself is the death of the ego. Many great deities like Siva and Kali, also represent death and transformation, Religion itself is mainly concerned with what, if anything in us, transcends death.

Death is the doorway to the world of the Gods or the immortals, the way beyond ktime and suffering. The God of Death or Yama in Vedic thought is also the twin brother of Manu, the primal man, representing death that is our constant companion and shadow throughout our brief mortal existence. Death or Mrityu is listed as one of the first great Upanishadic gurus in the Brihadaranyaka list of teachers. Indeed it can be said that the spiritual life itself is a kind of voluntary death and renunciation. The Vedic sacrifice is a retualized death experience for those who perform it. Its main goal is to take us beyond death, which is also to take us through death to the other shore of eternity beyond it.

Yoga itself is a kind of inner death experience or practice. Death is symbolic of yogic methods of Pranayama and Pratyahara in which the yogi withdraws his prana from the physical body, and in a simulated death experience, diver deep into the Self within the heart. Ramana Maharshi, a modern Nachiketa like the youth of this Upanishad, records suchg a yogic death experience as the basis of the Self – realization that occurred when he was a mere lad of sixteen. To find the deathless Self, we must first pass through death. We must die while living in order to discover the life beyond death.

Nachiketa represents the pure mind which seeks only to know the truth and cannot be distracted by the many other deseres and pursuits that characterize the ordinary human world. This pure mind voluntarily goes to the house of death. It sees the inherent impermanence of life and is not taken in by life’s alluring appearances. It voluntarily seeks death, knowing that to be the only real way beyond this world and its sorrow.

When one goes voluntarily to the house of death, like Nachiketa, one will find that there is no one home. Death only exists for those who are unwilling to die, who cannot give up their attachment to the body and the external world, which makes death real and final for them. Furthermore, when one goes voluntarily to the house of death, he becomes a guest, no longer under the power of death. Death no more has any claim over him. He becomes someone that death does not control but even death must honor. For him, the God of death becomes the great guru or teacher.

The three days that Nachiketa stayed in the house of death were without the owner of that house noticing him. It shows that the one who dies voluntarily cannot immediately be seen by death. He can experience death without having to be consumed by it. In that period, death death changes his nature for him. While for ordinary men, death collects his debts and karmas, for spiritually awakened seekers like Nachiketa, who can face and endure death, death becomes a giver of gifts. What cause this change? When we give up our pursuit of karma or results and pursue knowledge instead, then our debts and karmas disappeat or turn into knowledge. When the true seeker voluntarily dies, then death becomes a giver of the highest knowledge and the greatest boons. Pwehaaps no other story in the spiritual literature of the world so reveals this truth as this short Upanishad.

Nachiketa himself is a manifestation of Agni, the fire child, Kumara, our own inner child of immortality, which is why a special sacred fire or Nachiketa Agni is consecrated to him. He is also Sanat Kumara or the eternal child who never dies – the Divine soul and seeking of absolute truth within us. He is Skanda, the causal guru mentioned in the Chandogya Upanishad. Fire is the deity through whom we die, not simply as the power that cremates the body but also as power that purifies the mind and heart, the burning up of the ego and its Samskaras in the fire of knowledge (jnanagni).

The Upanishad provides the teachings of yogic dying that take us beyond karma and rebirth. As it is short and to the point, it has retained its prestige over longer and more circuitous teachings. It remains a practical manual for going beyond time and desire.

Sivananda Maurty

India has a long tradition of great teachers who used the Upanishads to express their insights and to awaken their disciples. Sivananda Murty is one of the most important of such modern masters. Thoug widely known in Andhra Pradesh, the region of India where he lives, he is little known in the West, which is generally still not able to discriminate between genuine spiritual yogis and mera yogaasana technicians.

Sivananda Murty is unique in that he has the knowlwdge of Yoga and its inner practices, as well the knowledge of Advaita and Jnana. In addition, he understands both the Vedic and Puranic traditions along with their main mantra and meditation practices. While there are many people East and West today who can talk about Advaita, which often gets reduced to a kind of “instant enlightenment’ fad, there are very few who actually know the way to achieve that supreme state by really going beyond death and transcending body consciousness. Few know the yogic methods that are usually essential for this transformation. In this regard, Sivananda Murty provides an example and a way to follow that restores the depth to these ancient teachings meant to really take us to the eternal, not merely as a belief or conviction but as a realization of our entire being.

Murtyji has chosen what is perhaps the most classical spiritual story of India, that of the Katha Upanishad, but has looked at it in a much deeper light than even the great Advaitic commentators of the past. He has elucidated it with the insights of Jnana, Yoga and Karma (ritual) combined, revealing all the layers of its manifold secrets back to its Vedic roots. He hasn’t reduced the text to one level only. He hasn’t simply used the text to reflect his own ideas or to promote a philosophical system but to stimulate the genuine seeker to real Yoga practices and introspection of the deepest kind. This makes his interpretation unique and of special interest to all those who value the Upanishads. It brings the Upanishads back in time into the Upanishadic age.

Perhaps most importantly Murtyji shows how Vedic rituals can be important to the path of Jnana or Self-realization, either as external Practices or as internal rituals and Yoga practices. He does this not by reducing knowledge to ritual, but showing the secret knowledge that can work through ritual and elevate it to a meditative act. In this way he restores an older Vedic approach that used ritual as a means of taking us to knowledge, neither denying its efficacy, nor reducing the pursuit of knowledge to it. He also shows how ritual can be used as an aid to win the higher worlds, even in absence of the seeking for complete liberation.

I have had the good fortune and grace to meet with Sivananda Murty on several occasions over the past ten years and to experience several aspects of his teaching and insight that cover almost every domain of Vedic and yogic thought and practice. This current Upanishadic book represents only one side of his vast knowledge. It has been my honor to go over this book and make adjustments of language when necessary to improve its communication. Hopefully, I have not anywhere interfered with its meaning or added anything extraneous.

The Purusha in the Heart

The Vedic ritual or Yajna is centred on Agni or the sacred fire, starting with the first verse of the Rigveda itself of Agnim Ile. Yet this Vedic ritual is not simply external (bahiryajna) on a fire alter but also internal (antaryajna), in ourown minds, or on the altar of our own hearts. So too, the Vedic fire is both outward (adhibhoutic) and inward (achyatmic), both a material and a spiritual reality.

The outer ritual worships the Divine with external substances like ghee and rice, which are placed into a fire started through wood and other flammable material substances. The inner ritual worships the Self in the heart by making internal offerings of body, speech and mind to the indwelling Divne fire, the flame of our own being and consciousness. The ultimate offering of this internal Self-sacrifice or Atma-Yajna is to offer one’s own mind and ego to the Divine, to consciously die into immortality. It is this inner sacrifice that we see in the story of the Katha Upaanishad.

The Purusha in the heart is Agni, who is our inner child or Kumara. This Kurmara, in its human form is Nachiketa. This inner fire is not fire as a mere element but the Purusha as the indwelling light of consciousness, a light that is circumscribed by the body into a flame the size of a thumb, the Angusthamatra Purusha, or the person the size of a thumb of the Upanishads. This thumb size light is also the linga, the pillar of light that is the subtle body or sukshma Sarira. The essential teaching of the Katha Upanishad is this mergence into the Self that manifests through the heart.

The Mahanarayana Upanishad makes this relationship clear in its famous Narayana Sukta. It speaks of the lotus of the heart as containing a great fire (Mahan Agni) that is responsible for bodily heat and supports the digestive fire in the stomach. In this flame is a streak of lightning at its crest which is the Jivatman or reincarnating soul, whose continual spark lights this fire and keeps it going. Ata the top of this lightning is the bindu, point or dot of the Paramatman, the supreme Self that is never born and never dies. Unfortunately, most commentators take this as a mere visual description for meditation and miss its profound reality as describing the soul in the heart.

Our spiritual journey is to return to this fire in the heart, to the lightning hidden behind it that is our real soul and finally to the point of pure light behind that, which is our true Self and Supreme Being. That point is the doorway to the infinite, the way beyond all darkness and sorrow. Only if we first become very small can we become vast. This requires that we die to the body, the mind and the external world. Death is that point of purification we must pass through in order to gain entrance into the world of eternity and infinity. Yoga teaches us various methods to accomplish this process that is the real journey of our souls from darkness to light.

Sivananda Murty in explaining the Katha Upanishad makes this process clear and relevant for all of us. We are grateful to him for clearing away the dust of time and the confusion of philosophers, and once more connecting us with the essential Upanishadic wisdom that is the soul of India and perhaps our most ancient and eternal way of Self-knowledge as a species. His book provides new light on the Upanishads and shows us how to use Yoga and Vedanta together to practically achieve our highest goals.

Introduction

This commentary on Katha Upanishad is an attempt to prepare the reader to understand and appreciate the subtleties and secret messages contained in this Upanishad. Unlike other Upanishads, this Upanishad contains an episode, a happening, the performance of a Yajna, the accompanying charity and a little boy questioning his father to know to whom he himself would be gifted away along with the resultant annoyance of the father and an unmeant curse, all these ingredients kpresent an unplanned incident described as the background of the Upanishad. Nachiketa’s meeting with Yama, the God of Death, his brief interview with him, and what has transpired from it require a deeper analysis.

The incident itself is far from natural. Hence, it has to be explained what exactly was meant by Nachiketa traveling, waiting and meeting with Yama and finally returning to his father. This has been explained in the chapter “Yoga –Chakras and Kundalini (Chapter 7)”. Yama’s boon is a kind of initiation that leads to unravelling the mystery of creation which is the very secret sought by Nachiketa. The mantra part of the initiation is only Omkara which is neither new nor unprecedented. But then the tacit path indicated is the Anahata chakra. Her lies the great secret meaning of the very name or title of the Upanishad, KATHA. Anahata chakra contains a twelve petalled Lotus which are the seats of twelve mystic syllables, “Ka” to “Ttha”. This is the hidden secret of Yama’s path, which is secretly embedded in the very title of the Upanishad. This commentary is chiefly meant to unravel this mystery.

This work is in two parts. The first part consisting of chapters 1 through 7 is aimed at providing the read4er with the necessary foundation to go through the text proper.

Chapter I: The mysterious phenomenon of Death, the death-experience and the possibility of escaping the pain of death and death itself, thereby achieving a continuity of the inner-man are explained in this chapter.

Chapter II: The Vedic tradition consisting of an external ritual with its spiritual meaning are explained. The ‘Oneness’ and the complimentary nature of the Vedic ritual and Vedanta are brought out in this chapter.

Chapter III: The strange incident of Nachiketa travelling to the ‘world of souls’ is explained to prove the reality of the various Vedantic and Upanishadic assertions.

Chapter IV: This chapter deals with the subtle deals with the subtle body which is the in–dweller, who uses the instrument of the physical body in this earthly life. The famous historic Aswamedha as a technological means of the performer merging him with the Prajapati is also explained in this.

Chapter V: The Nachiketagni, a new invention, taught by Yama which is the combination of the rite and the spirit is explained in this chapter.

Chapter VI: The already existing paths to emancipation like the Samkhya and the Brahma Sutras and the path of Devotion are explained here.

Chapter VII: We hear stories of Parakaya pravesha vidya, namely the yogi entering into another human body and acting therein. The secret science involved in this is briefly placed before the reader. This chapter contains the very heart of this Upanishad, namely the Anahata Chakra. The name of the Upanishad is for the first time derived from the mystic syllables contained in the Lotus of the Yogic Centre, Anahata; “Ka” as the first and the “Ttha”, the last of the twelve syllables on the Lotus.

In the second part, the first three of the six sections (Vallis) of the Upanishad are commented upon in detail. The other three Vallis are summarized briefly.

Mere philosophical explanation for the sake of establishing an advaitic view may not justify the birth of this unique Upanishad. This Upanishad would then become redundant in the presence of other purely philosophical Upanishads. Hence Kathopanishad is unquestionably establishing a yogic path for the conquering of death and to the final absorption in Brahman. Here is an effort to establish Yoga as a path leading to a direct experience of the ultimate truth, often described as ‘aparokshanubhuti’ rather than a ‘parokshanubhuti’ or an indirect semblance of experience by an intellectual understanding of the ultimate truth or otherwise.

It is thus, the Upanishad more appropriately deserves to be called Katha-Yoga.

Contents

| Preface | 9 | |

| Foreword by David Frawley | 10 | |

| Katha -Yoga: An Appreciation by Pullela Sriramachandrudu | 18 | |

| Introduction | 31 | |

| Chapter 1. | The Phenomenon of Death | 1 |

| Escape from Death | 2 | |

| The Experience of Death | 3 | |

| The Soul's Permanence and the Individual's Impermanence | 3 | |

| Conquering Death | 4 | |

| The Individual and his Contunuity | 6 | |

| The Teacher-Disciple Tradition | 7 | |

| The Triple Sacrifice: Visvajit | 8 | |

| Yama as the Guru and Benefactor | 9 | |

| The Philosophy Involved | 9 | |

| Chapter 2. | Background of the Upanishad:Yajna,Tapas and Yoga | 10 |

| Yajna and Sacrifive | 10 | |

| Spirituality and Sacrifice | 11 | |

| Yajna and Tapas | 13 | |

| The True Yajna and its Decline | 14 | |

| Vedantaand Sadhana | 15 | |

| Medieval and Modern Society | 15 | |

| Advaita and Duality | 16 | |

| This Humble Attempt | 17 | |

| Chapter 3. | The Episode of Nachketa | 20 |

| The Episode - a Further Examination | 20 | |

| The Ingredients of the Upanishad: | ||

| The Relevant Brahmana,Visvajit Yaga: | 22 | |

| Nachiketa's Experience: Some Question | 24 | |

| Chapter 4. | The Subtle Body and the self within the Heart | 27 |

| Linga Sarira:The'Individual' Soul | 27 | |

| The Secret of the Angushtha Purusha | 29 | |

| The Five Sheaths | 31 | |

| Asvamedha Yaga:Yaga with Yoga Concept: | ||

| Retracing the Steps of Creation | 33 | |

| The Story of Bhujyu and the Sukla Yajurveda | 39 | |

| Chapter 5. | Nachiketa's Yoga | 43 |

| Yoga and Om | 43 | |

| Nachiketa Agni and Yoga | 45 | |

| The Agni Ritual, its Details and Meaning | 45 | |

| Crossing the Three Junctures | 46 | |

| Anaahata | 48 | |

| Reaching Higher Worlds through Yoga | 48 | |

| Chapter 6. | The Self Within the Heart and the Paths of Yoga | 50 |

| Sankhy and Yoga | 50 | |

| The Path of Devotion to the Form of God | 52 | |

| Brahma Sutras: The Jivatman | 53 | |

| Prana and Skti | 58 | |

| Chapter 7. | Yoga Chakras and Kundalini | 63 |

| Yoga Chakras and the Human Body | 63 | |

| Parakaya Pravesa Vidya | 67 | |

| Breath Control or Pranayama | 71 | |

| Anaahataand Bodily States | 72 | |

| Significance of the name Katha: the Heart-centre of the Upanishad | 74 | |

| Sri Gorakshanth: the Great Guru of Yoga | 77 | |

| The Katha-Upanishad | 79 | |

| A Gneral Commentary on Vallis I to III | 81 | |

| First Section - Prathama Valli | 82 | |

| Second Section - Dviteeya Valli | 94 | |

| Third Section - Triteeya Valli | 105 | |

| A General Commentary on Vallis IV to VI | 112 | |

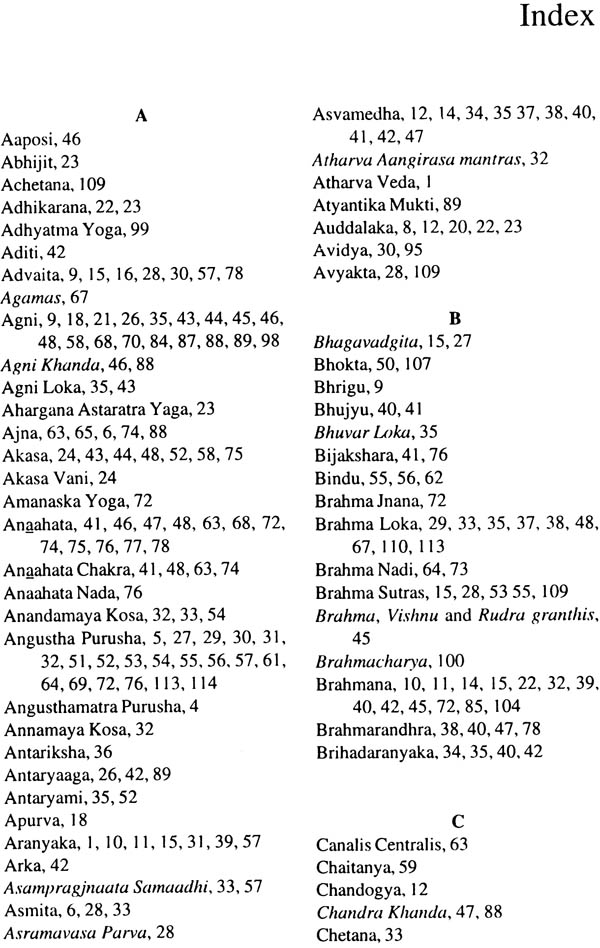

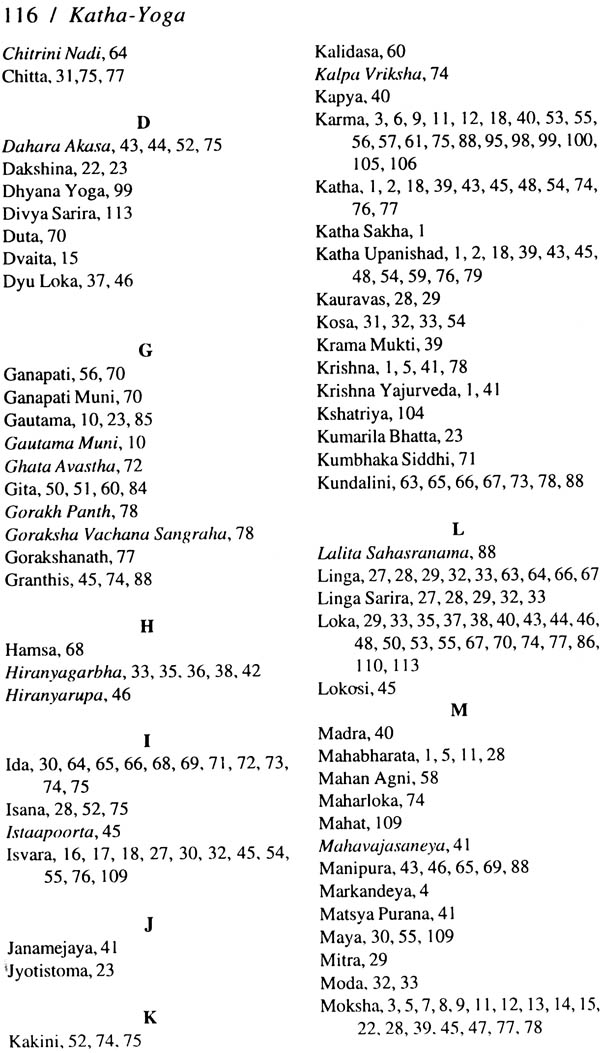

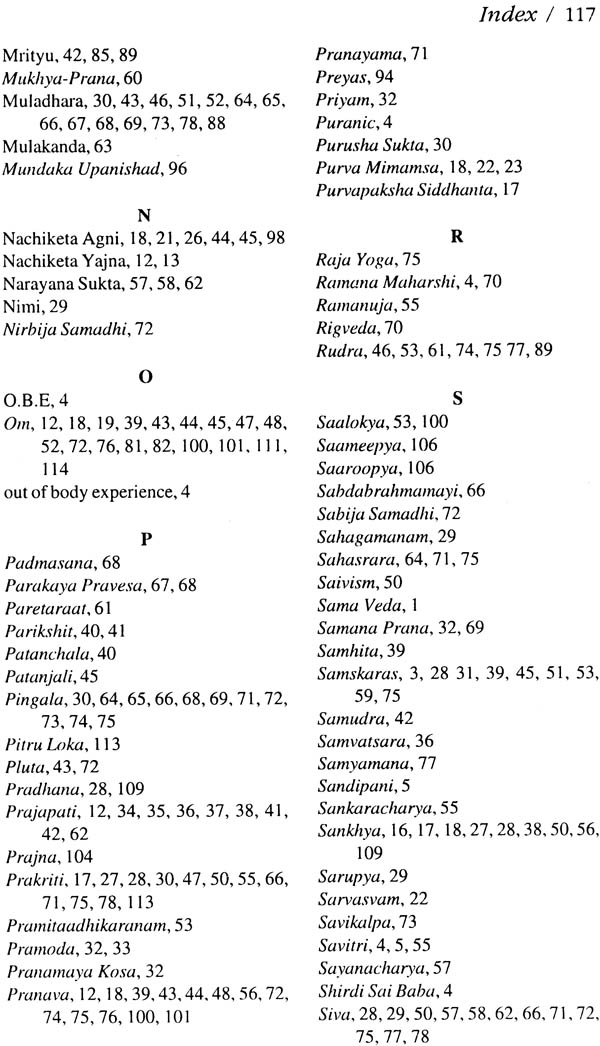

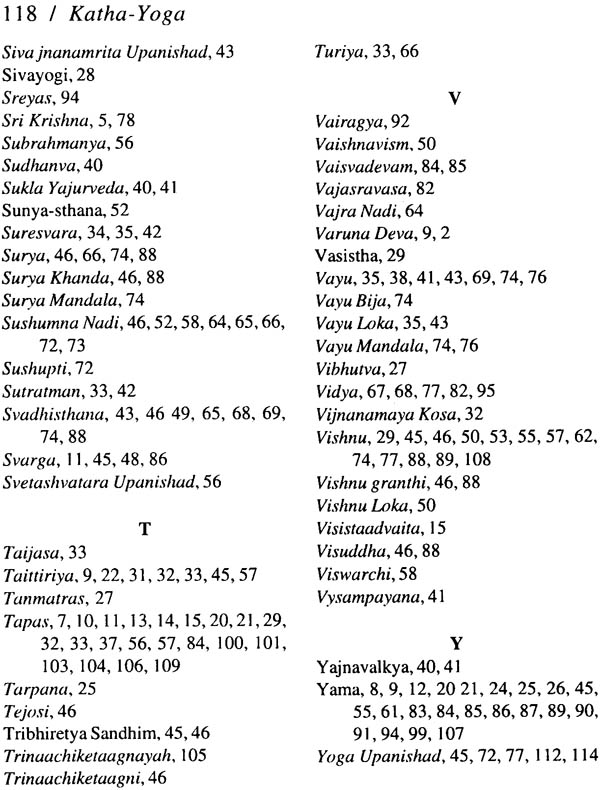

| Index | 115 | |

| Bibliography | 119 | |

| Diacritical Markings - Pronunciation | 120 |