Quiver (Poems and Ghazals)

Book Specification

| Item Code: | NAG361 |

| Author: | Javed Akhtar and David Matthews |

| Publisher: | Harper Collins Publishers |

| Language: | English |

| Edition: | 2012 |

| ISBN: | 9788172235123 |

| Pages: | 263 |

| Cover: | Paperback |

| Other Details | 8.5 inch X 5.5 inch |

| Weight | 230 gm |

Book Description

For audiences in India and Pakistan, Javed Akhtar requires no introduction. His film alone have gained him universal recognition, and his lyrics, which have been sung by some of India’s most famous vocalists, are known to everyone. Although in his verse he frequently refers to his own shortcomings and ineffectualness, his life has been one of outstanding success.

Perhaps the reason for the great popularity of Javed Akhtar’s verse is that on the surface it appears disarmingly simple and direct, but frequently it has something profound and significant to communicate. It is thoughtful without being pretentious. Javed Akhtar is always capable of putting into words and thought and ideas which all of us have but which we are seldom capable of expressing with such irony, without the attendant cynicism.

The poems contain the poet’s reminiscences of his childhood, and bemoan and loss of its innocence with the passages of time. The poems are also about love - its complication, pains and even its joys. But even the simple love poems usually contain a much deeper message; it is up to the reader to explore the various levels of meaning for himself or herself. There are also a number of lengthy philosophical poems where the poet asks simple questions to which the response remains a mystery.

For audiences in India and Pakistan, Javed Akhtar requires no introduction. His films alone have gained him universal recognition, and his lyrics, which have been sung by some of India's most famous vocalists, are known to everyone. Although in his verse he frequently refers to his own shortcomings and ineffectualness, his life has been one of outstanding success. Having graduated from Saifiya College in Bhopal, he eventually made his way to Bombay, just as many in the Urdu-speaking community of India had done before him. There the growing film industry provided him with the opportunity to exploit his talent for writing to the full.

Before the fall of the last remnants of the Mughal dynasty in 1857, Urdu poets, who could hardly make a living from what they wrote and published, looked to the courts of Delhi, Lucknow and Hyderabad, and to the great houses of the nobles for patronage. When the old order collapsed and aristocratic families were no longer able to afford the luxury of keeping a private group of poets to adorn their courts, aspiring writers were obliged to look elsewhere. Although during the later stages of British rule. Urdu, once regarded as the language of culture and refinement par excellence, suffered a number of setbacks, it still held on to its prestige. The ghazal, a form of lyric verse which had its origins in medieval Persia, remained eternally popular, and traditional poetic gatherings, known as mushairas, continued to attract, as they still do, audiences of thousands. The story of the broken-hearted lover frustrated in his endeavours to approach his cruel, uncaring mistress, the images of the lonely bulbul singing its heart out in the garden decked with the tulip and the rose, the fervent desire for annihilation and escape from the material world and the dream of attaining union with the creator-all these elements of the ghazal. with its elegant Persian diction, were instantly familiar to people of whatever religion, caste or social background. It is, of course, the ghazal that people have in mind when they refer to Urdu's 'sweetness'.

In the early decades of the twentieth century, Urdu poets turned their attention in other directions. The growing impatience for independence from the British rule and the fervour of the freedom movement provided many with an outlet for their talents. At that time, for expressing dangerous political views in particular, verse could be even more effective than prose. Many young progressive writers like Javed's father, the eminent poet, Jan Nisar Akhtar, emerged largely from the small towns of Uttar Pradesh, where Urdu had been born and had been cultivated for centuries. These writers used their skill and energy to produce a vigorous modern literature, which played a significant role in currying the subcontinent along its path to independence. Here the place of poetry cannot be underestimated, and the names of Ian Nisar Akhtar, Kaifi Azmi (Javed Akhtar's father-in- law), josh Malihabadi, Ali Sardar Jafri, Majruh, Faiz Ahmad Faiz and Javed Akhtar's maternal uncle, Majaz, to name but a few, have become legendary. Many of them spent periods of time in jail for the views and beliefs which were expressed in their writing.

This is a clear indication that their British masters took the power of verse very seriously indeed. Urdu was never the exclusive preserve of one people and many Hindus and Sikhs joined the ranks of its largely Muslim writers, nor was it restricted to only one region of India, but was written and spoken and cultivated in cities as far apart as Delhi, Lahore, Karachi, Bombay, Hyderabad and Calcutta. Even though, largely for political reasons, the language has in recent years suffered a decline, the verse and prose of these early 'progressive' writers is still remembered with a respect which often borders on awe.

When independence was finally achieved and the film industry of Bombay began to grow, talent for providing scripts and for composing songs, which always form an essential part of a Hindi film, was urgently required. It was largely from this well-established group of Urdu writers that it was sought. From the 1950s onwards, perhaps, it would be fair to say that Bombay replaced the Red Fort as the new bastion of Urdu poets.

When writing for films, poets, novelists and musicians at the same time continued with their 'more serious' work, applying all their skills and traditions to the scripts they prepared. For this reason it is often impossible to distinguish between a film lyric and a carefully constructed poem, written according to norms of classical verse. In the West popular songs are not normally written by 'serious' poets, but in India they usually are. In the subcontinent classical poetry is still very much a part of the fabric of everyday life, and many people with no particular literary education-they might be engineers, doctors, taxi-drivers or waiters-can recite scores of verses from memory. In Britain it would be hard to find anyone with such a knowledge of Keats, Byron or Shelley. There, poetry is usually read, if read at all, from books. In India and Pakistan it is recited on the street and in cafes.

| About Myself | 1 |

| Introduction | 15 |

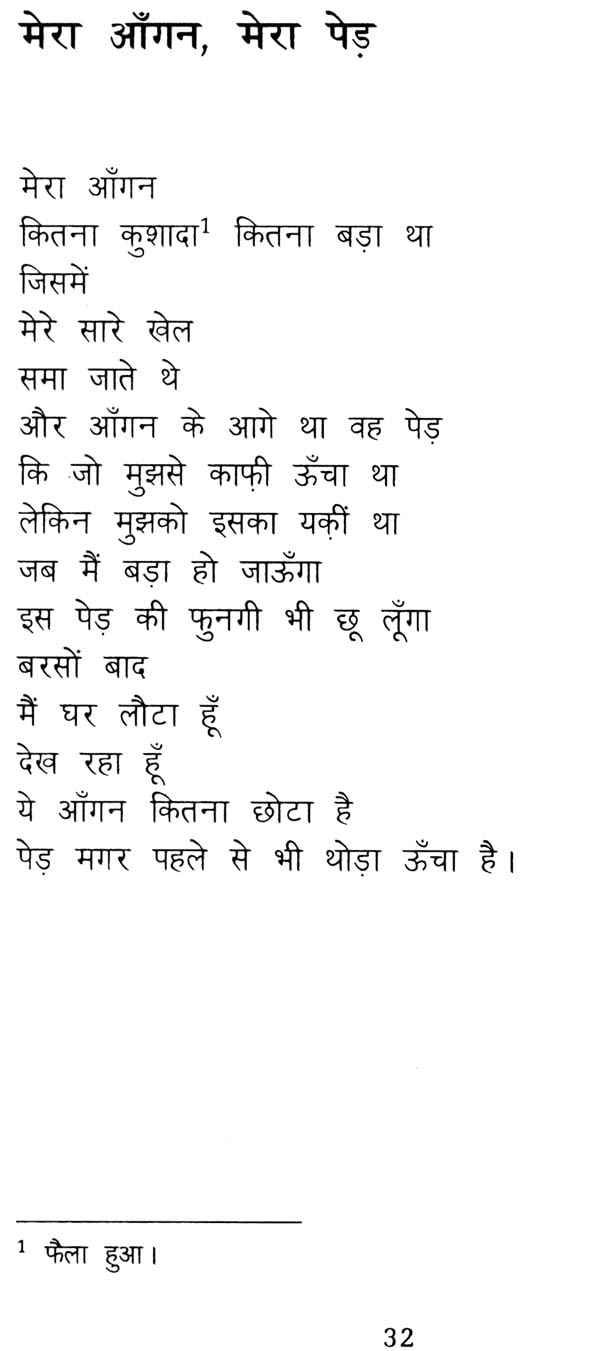

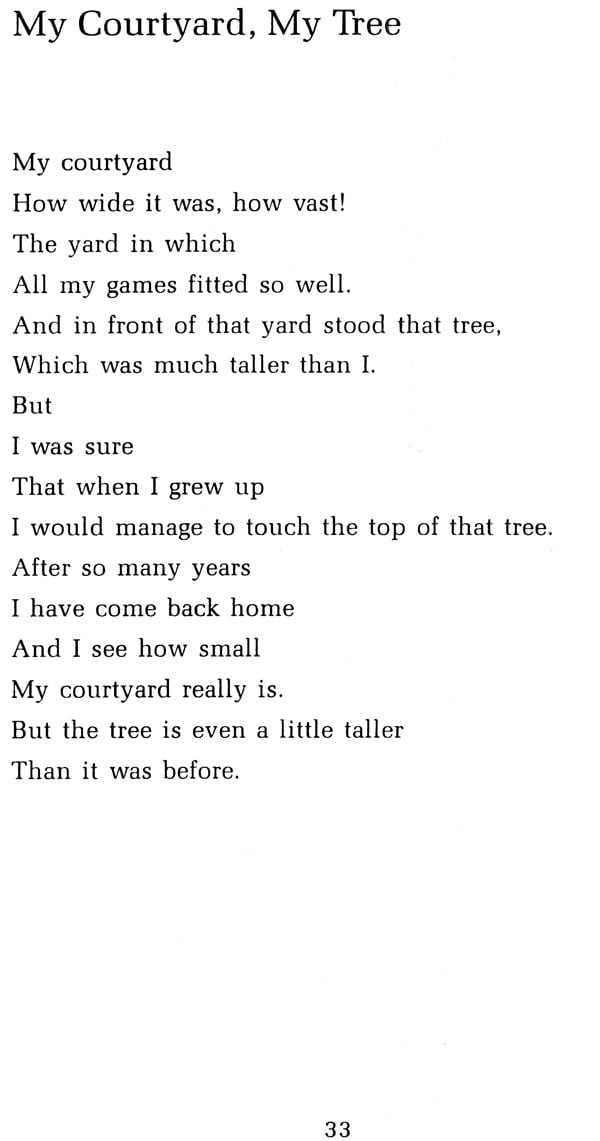

| My Courtyard, My Tree | 33 |

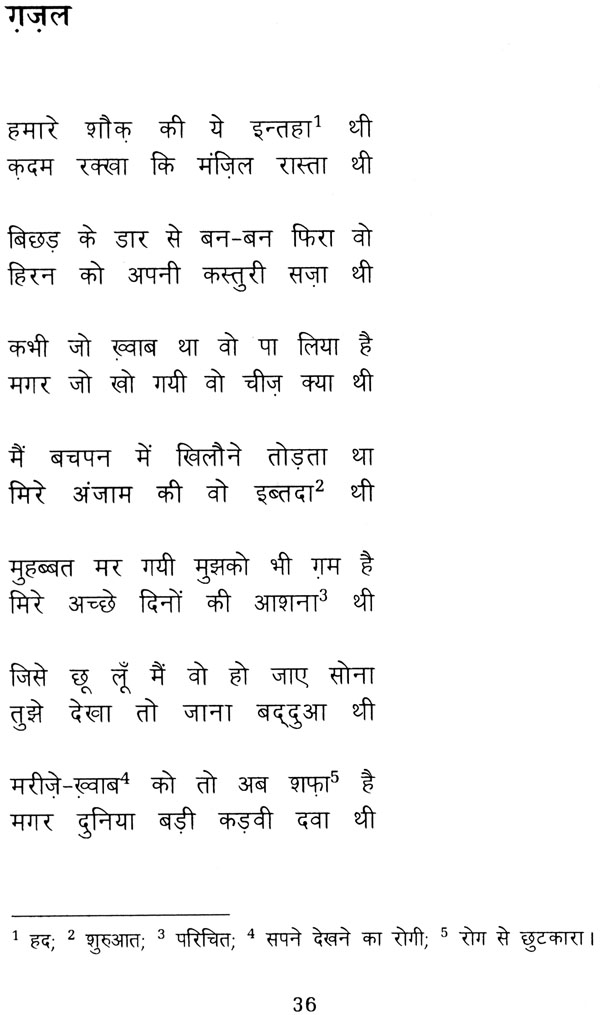

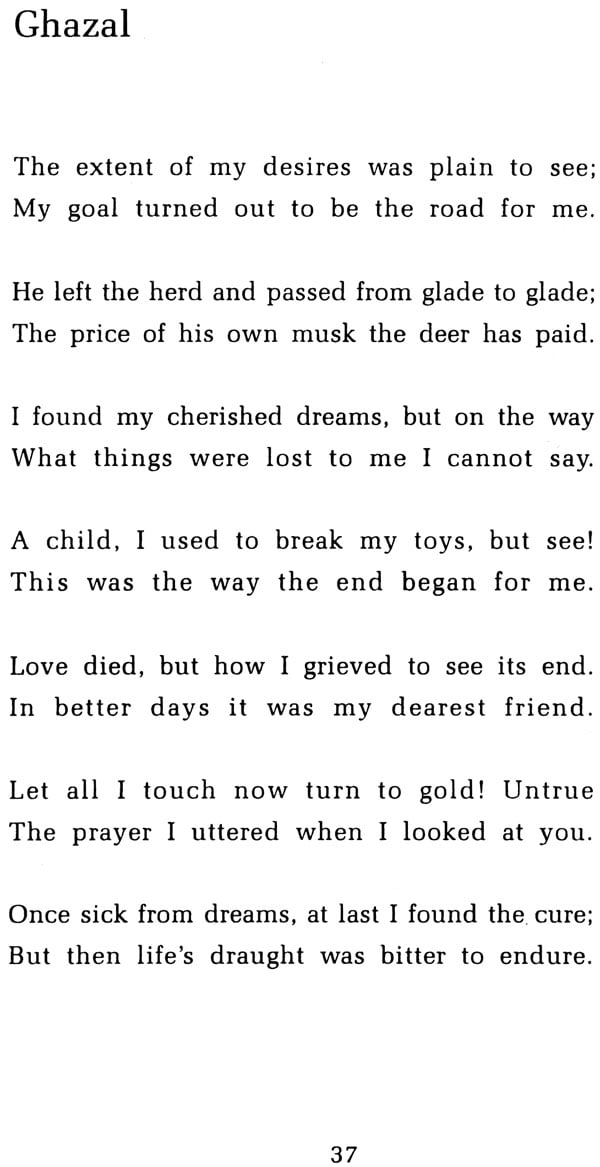

| Ghazal | 37 |

| I Remember That Room | 39 |

| Ghazal | 47 |

| Hunger | 51 |

| Ghazal | 63 |

| Banjara | 67 |

| Ghazal | 75 |

| Ghazal | 79 |

| The Journey of a Pawn | 83 |

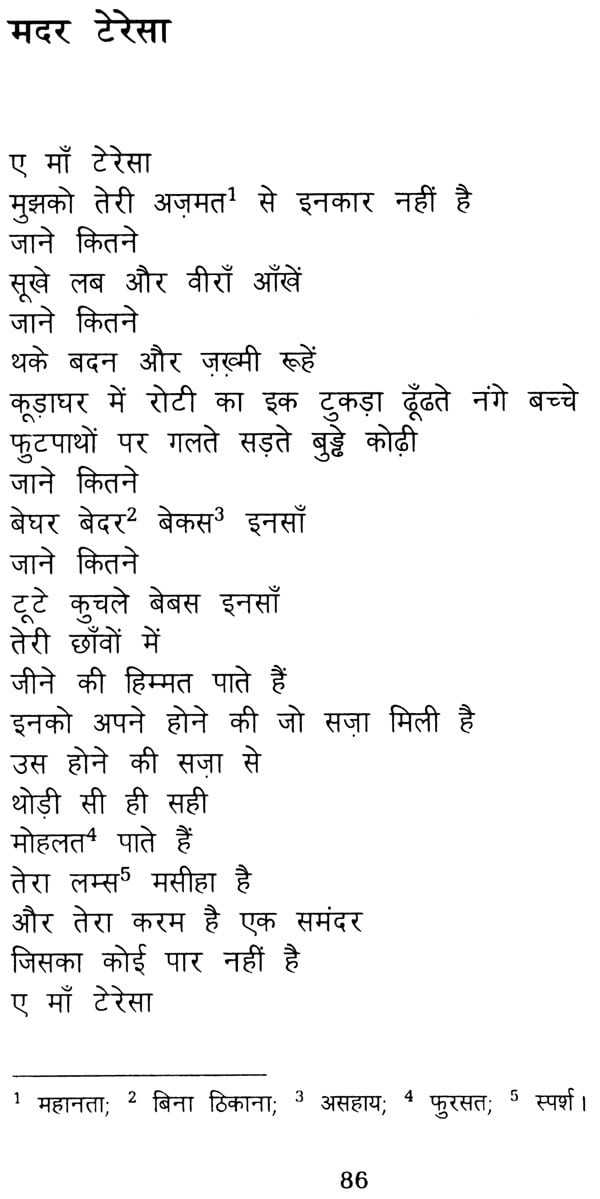

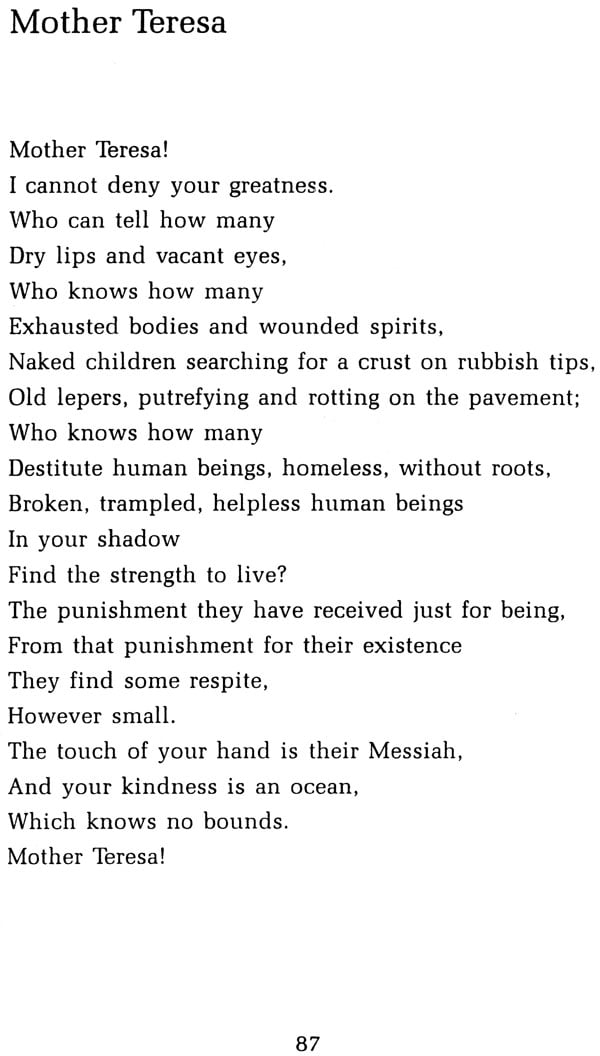

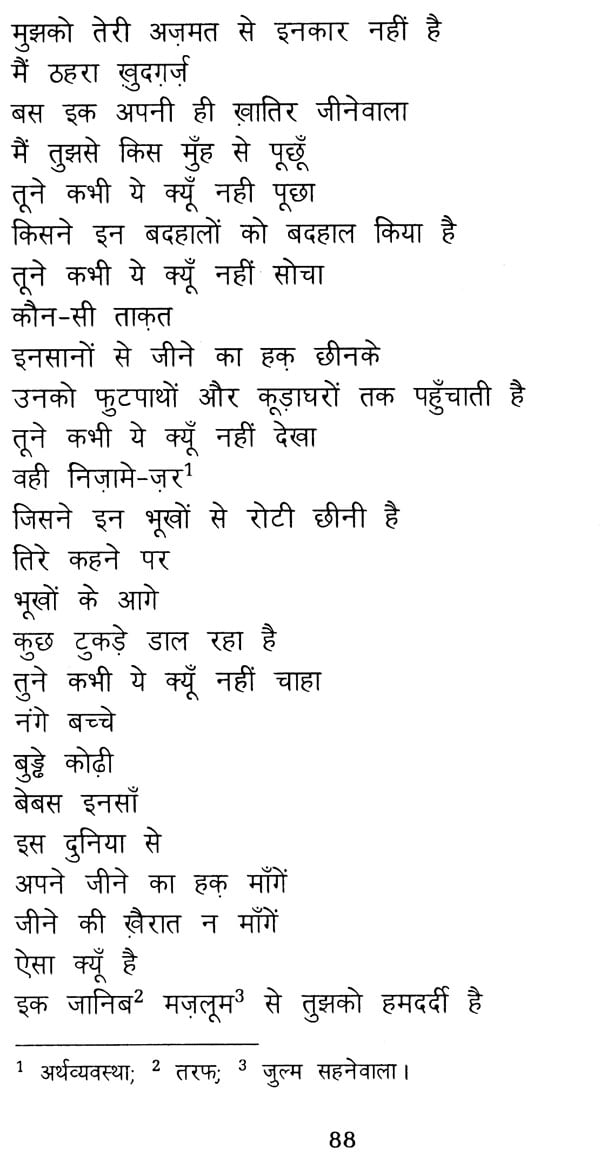

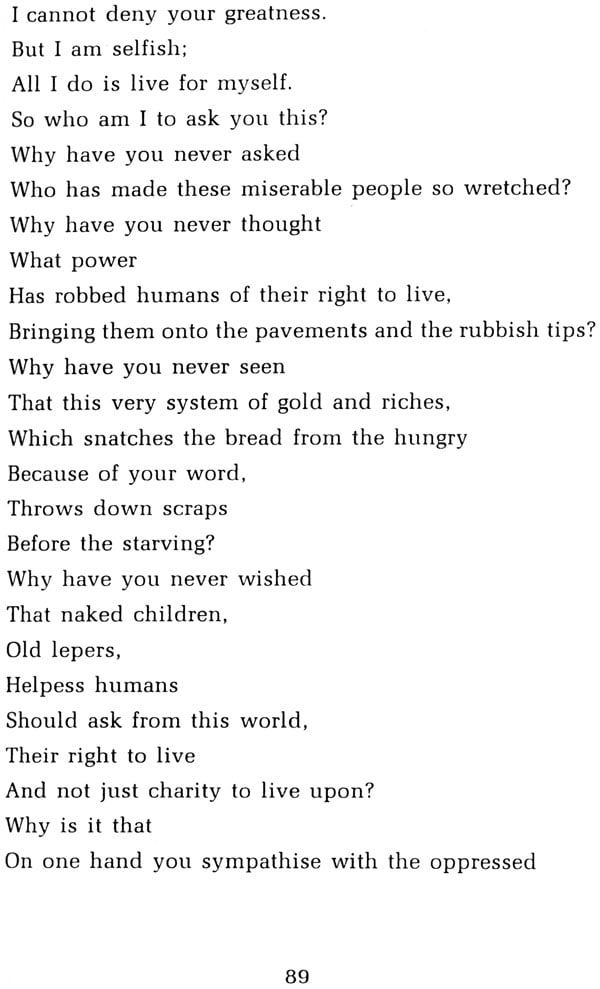

| Mother Teresa | 87 |

| Before the Riot | 95 |

| Ghazal | 99 |

| After the Riot | 101 |

| Ghazal | 105 |

| Ghazal | 109 |

| Ghazal | 113 |

| Riddle | 117 |

| Perplexity | 121 |

| Infernal | 125 |

| A Night of Illness | 129 |

| Ghazal | 131 |

| Ghazal | 133 |

| Ghazal | 137 |

| Defeat | 141 |

| Ghazal | 149 |

| Ghazal | 153 |

| Ghazal | 157 |

| Apart | 161 |

| Dilemma | 165 |

| Remains of the Past | 169 |

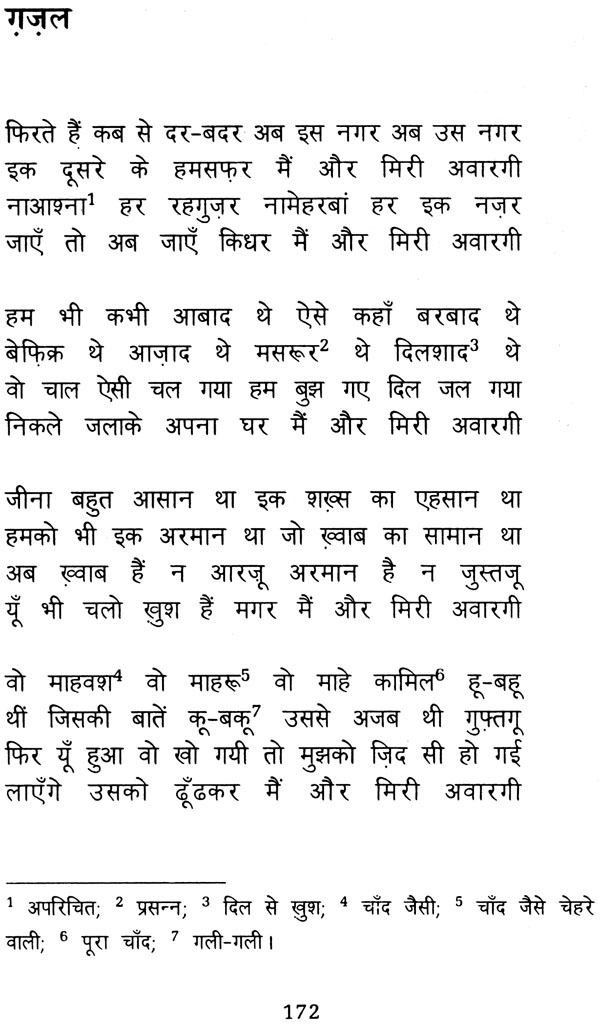

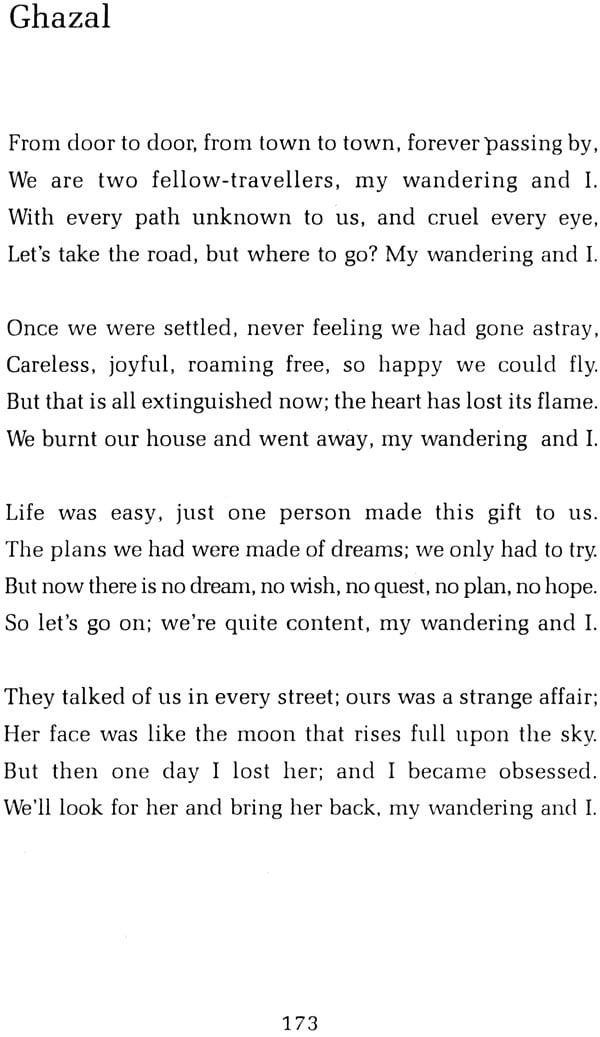

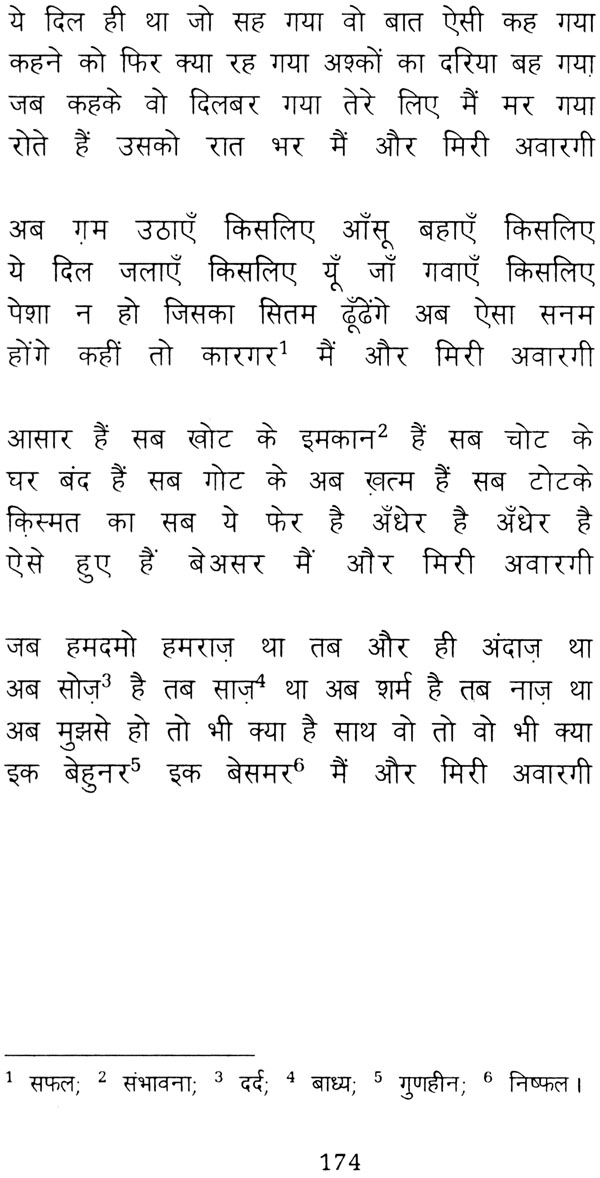

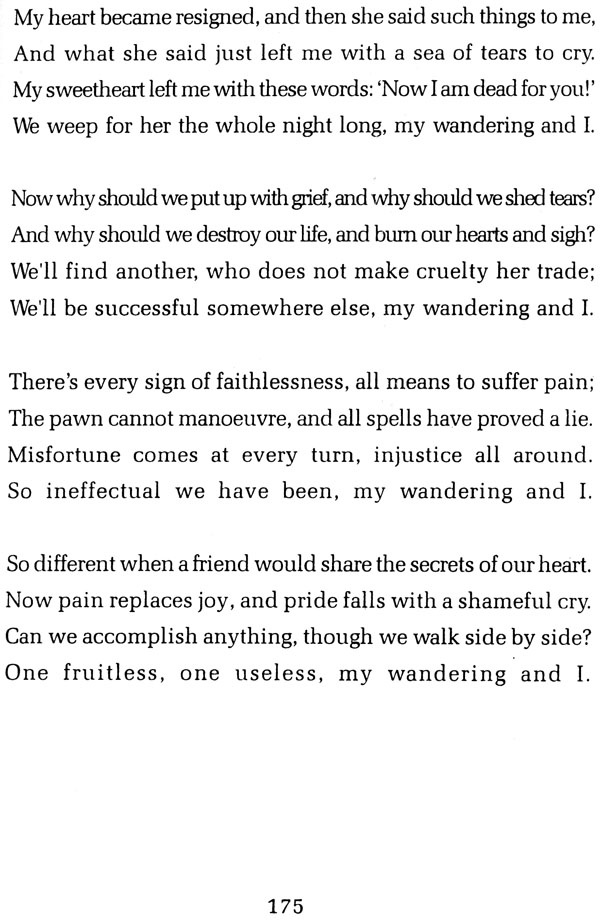

| Ghazal | 173 |

| Sorrow for Sale | 177 |

| Come Now and Do Not Think | 181 |

| Ghazal | 187 |

| Time | 191 |

| Ghazal | 203 |

| Ghazal | 207 |

| Crossroads | 209 |

| Ghazal | 217 |

| Ghazal | 221 |

| Morning Maiden | 225 |

| My Prayer | 227 |

| Ghazal | 233 |

| Ghazal | 237 |

| Crime and Punishment | 239 |

| Hill Station | 245 |

| Four Short Verses | 249 |

| Homeless | 251 |