Theory and Practice of Temple Architecture in Medieval India (Bhoja’s Samaranganasutradhara and the Bhojpur Line Drawings)

Book Specification

| Item Code: | NAJ907 |

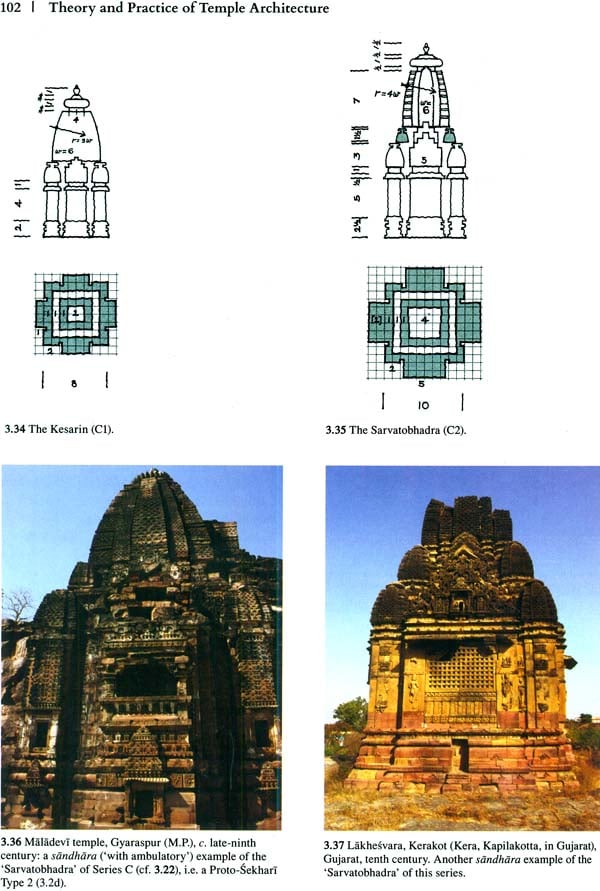

| Author: | Adam Hardy |

| Publisher: | Dev Publishers and Distributors |

| Language: | English |

| Edition: | 2015 |

| ISBN: | 9789381406410 |

| Pages: | 309 (Throughout B/W and Color Illustrations) |

| Cover: | Hardcover |

| Other Details | 12.0 inch x 8.5 inch |

| Weight | 1.50 kg |

Book Description

About the Book

This book is about vastuvidya or architectural theory, the creation of temples, and the role of drawing as an indispensible bridge between the two.

It focuses on two works attributed to Bhoja, the legendary Paramara ruler of Malwa in the first half of the eleventh century. The first of these is his vastly ambitious, but unfinished, royal temple at Bhojpur, with its unique set of architectural drawings engraved on the surrounding rocks. These beautiful drawings, documented here for the first time, provide insights into construction processes and glimpses of hitherto unknown temple forms. They also hold the key to the intended design of the Bhojpur temple itself, which would have been by far the biggest Hindu temple in the world.

The other main focus of this study is Bhoja's great compendium of architectural knowledge known as the Samaranganasutradhara, a project of comparable ambition to his temple. This famous Vastusastra was compiled at a moment when the classical traditions of Indian architecture had blossomed into abundant maturity, and could be understood in relation to one another, in all their diversity. The Samaranganas treatment of Nagara, Dravida and Bhumija temples are covered here in detail, with key chapters translated both into English and into drawings of the temple designs that the text encapsulates. As illustrated by numerous photographs, the text describes types known among surviving monuments, as well as many others probably never built. Far from being a straight jacket and an impediment to growth, the text, is revealed both as full of architectural invention, and as a framework and a stimulus to further creativity. This book will allow the reader to begin to understand the temple architecture of medieval India through the eyes of its creators.

About the Author

Adam Hardy, an architect, is Professor of Asian Architecture at The Welsh School of Architecture, Cardiff University. He has been studying Indian temples for more than thirty years, and his publications on the subject include Indian Temple Architecture: Form and Trans-formation (IGNCA, 1995) and The Temple Architecture of India (Wiley, 2007). Since 1999 he has been Editor of the journal South Asian Studies. He is currently working on two projects which, like the study for this book but in different ways, re-create traditional temples. One is a conservation study for the World Monuments Fund at Ashapuri, Madhya Pradesh, involving the recovery of lost temple designs from thousands of stone fragments; the other is the design of a new temple in Hoysala style near Bangalore, aiming to unfold the inherent potential of that tradition.

Foreword

This highly specialized study on "Theory and Practice of Temple Architecture in Medieval India" is indeed a monumental work and we at IGNCA are very happy to place it in the hands of readers. Medieval architecture is precisely dated to the beginning of the tenth century. As observed by a scholar, "Medievalism in North India simultaneously manifested itself in all regions and in almost all fields of cultural expressions - literature in its manifold modes, elaborate ritualistic forms of worship, costumes and ornaments, music and dance, and above all art and architecture, converging as they all did to the same ideals and exhibited identical inward spirit and external unity in formal appearance. Architecture, by an assured, as though pre- determined, course of evolution, by then had left behind the relative simplicity, undue massiveness, ponderousness of appearance met with in the earlier ages. The medieval era ushered in the first definite stage of creating fully organic, highly integrated, and convincingly articulate appearance of a 'temple' as it will look, or should look, as Gothic era contemporaneously was to do in the medieval Europe for the 'Church'. (M. A. Dhaky, Encyclopedia of Indian Temple Architecture, Vol. II, Part 3, North India, Text p. xxi). Some of the greatest masterpieces of temple architecture were created in this age. Sadly, much of the material contribution of this period has now vanished due to the ravages of time and the vagaries of man.

The temple site of Bhojpur (Madhya Pradesh) is associated with Bhoja, the legendary Paramara ruler of Malwa in the first half of the eleventh century. The present volume focuses on two works attributed to this illustrious ruler. The first is a vastly ambitious, but unfinished, royal temple at Bhojpur, with its unique set of architectural drawings engraved on the surrounding rocks. These beautiful drawings, documented here for the first time, provide insights into the construction processes and glimpses of hitherto unknown temple forms. They also hold the key to the intended design of the Bhojpur temple itself according to investigations made by Prof. Adam Hardy. The other main focus of this study is Bhoja's great compendium of architectural knowledge known as Samaranganasutradhara, a project comparable in scope and ambition to his temple. This famous text on architecture (Vastusastra) was compiled at a time when the classical tradition of Indian architecture had blossomed into abundant maturity, and could be understood in relation to one another, in all their diversity. As illustrated by numerous photographs in the present volume, the text describes types known among surviving monuments, as well as many others probably never built. The text is revealed here both as full of architectural innovations and as a framework and stimulus to further creativity. In this context, I am delighted to inform that IGNCA has already got prepared a critical edition with the translation of the complete text of Samaranganasutradhdra. It will be brought out soon in the Kalamulasastra series of fundamental texts.

I am grateful to Prof. Adam Hardy for preparing this volume for IGNCA. We are privileged to bring it out under the series of analytical studies-the Kalasamalocana series. IGNCA has published several works on architecture under various programmes. Dr. Advaitavadini Kaul has summarized all these works in her preface. I would also like to record my thanks to Dr. Mattia Salvini for assisting Prof. Adam Hardy and translating the portions of Sanskrit text.

It is hoped that the present volume will allow the readers to begin to understand the temple architecture of medieval India through the eyes of its creators.

Preface

That the Indian arts emerge from a unified world view has become well established now. Earlier, all arts were treated in isolation or looked from different paradigms. In the latter half of the nineteenth century and early twentieth century, scholars from all over the world were drawn to the Asian heritage. Some excavated, others brought to light primary textual material, and a third group dwelled upon fundamental concepts, indentified perennial sources, and created bridges of communication by juxtaposing diverse traditions. Acting as path- finders, they drew attention to the unity and wholeness of life behind manifestation and process. Cutting across all notions, they were responsible for laying the foundations of a new approach to Indian and Asian Arts, characterized by a depth and width of vision. The work of these trailblazers has been of contemporary relevance and validity for both the East and the West. Restless and dissatisfied with fragmentation, both are currently engaged in a search for roots and for comprehensive perception and experience of the whole.

The Kalasamalocana series of IGNCA is devoted to the publication of the interpretative and analytical works of these pioneers, who have been torch bearers to illuminate the search for the roots. Seventeen volumes of Ananda K Coomaraswamy were published in this series. So also were brought out the works of pioneers like M. Hiriyanna, Stella Kramrisch, Alice Boner, Seyyed Hossein Nasr. Other major works also have been published focusing on India and the creative artistic traditions of other parts of Asia such as Barabudur; Rama-legends and Rama Reliefs in Indonesia; Iconography of Avalikitesvara in Main- land South East Asia; Dunhuang Arts; Ajanta: Narrative Wall-paintings and many more.

The critical scholarship on Indian temple architecture has come a long way since the time when scholarly concern in this field was confined to the material form. The archaeologists studied Indian temple architecture through the application of methodological tools and the Sanskritists who indentified texts and even compiled glossaries did not have the technical wherewithal to examine actual monuments. It was around the early nineteenth century that James Prinsep tried to evaluate northern Indian shrines in the light of vastusastra traditions and Ram Raz tried to relate temple architecture to the living cultural traditions of South India. However, it was Ananda K Coomaraswamy who gave a new turn to the study of Indian and Asian architecture by delving deep into literary sources and related concepts as well as technical terminology for assessing monuments, stupas and temples alike. He drew attention to the origins of monumental architecture in huts and humble dwellings. Giving a fresh perspective to the study of Indian architecture, his writings on the subject edited by Michael W Meister have been brought out in two volumes as Essays in Early Indian Architecture and Essays in Architectural Theory in the Kalasamalocana series.

Stella Kramrisch contributed by way of providing the perception for understanding Indian art. More specifically, she changed the course of critical studies on temple architecture. "Stella had known and experienced the Himalayan mountains and had investigated the textual traditions of the Brhat Samhita and other Vastu texts. She had studied the rituals described in the Satapatha-Brahmana. It was the interconnection of the Vedic ritual and texts of Vastu and the experience of the Himalayas which coalesced into that great work 'The Hindu Temple'. In this work, she brought together textual sources which had so far been comprehended in isolation. For the first time, she established a relationship between not only diverse texts and the fundamental importance of the Vastu purusa mandala and the ritual but also to the significance of making temples in the confluence of rivers, of the pure waters of the snows. The temple was both Purusa and Guha, the co-ordinate of Meru and in turn was the vehicle of Man's journey to transcendence. These insights ignited a new line of scholarship in Indian temple architecture post - 1960. Coomaraswamy responded not through a review instead through the great essay on Kandariya Mahadeva".' A volume of selected essays from a vast body of her works was published in the series in 1993. This volume represents the manifold contribution of Stella Kramrisch in opening up doors of perception for understanding Indian art.

The Principles of Composition in Hindu Sculpture published in the series in 1990 is the result of the revelations by a sculptor. " Alice Boner, a trained western sculptor, a keen observer of visual forms, responded with refined sensitivity to plasticity everywhere. She came to India charged with the fire of movement of dance, was be stilled with the central dynamism of Ellora caves. Without aid of texts and conventional guidelines, the monumental reliefs of Ellora, the dynamic movement of the dance arrested in stone shed all flesh and muscle and revealed the essence of the bone structure to Alice ... Her eye was flawless, her argument born out of actual experience has been confirmed during these decades by a corpus of textual material. She herself followed the Principles of Composition by textual work relating to the Orissan texts Silpa Prakasa and Vastusutra Upanisad"?

The text of Silpa Prakasa was first discovered, edited and translated by Alice Boner. A revised version prepared by Bettina Baumer et al with new illustrations, on the basis of a palm leaf manuscript and with added indices was published by IGNCA in 2005 under the programme of fundamental texts - the Kalamulasastra series. Another Orissan text published in this series in 1994 was Silparatnakosa (17th cen). It describes all the parts of the temple and the most important temple types of Orissa, such as the Manjusri and Khakara. It also contains a section on sculpture (prasadamarti) and an appendix on image-making. Mayamatam (11 th-12th cen) also published(1994 first edition & 2007 third reprint) under the fundamental texts is a comprehensive vastusastra edited and translated by Bruno Dagens along with an insightful introduction and an exhaustive glossary of technical terms. It deals with all the facets of gods' and men's dwellings, from the choice of the site to the iconography of the temple walls. It contains numerous and precise descriptions of the villages and towns as well as of the temples, houses, mansions and palaces. It indicates, for the selection of a proper orientation, the right dimensions, and appropriate materials. Well thought of by traditional architects (sthapatis) of South India, it is debatable whether the text precedes or succeeds the construction of the Brhadisvara temple. The treatise has proved of great interest at a time when technical traditions, in all fields are being scrutinized for their possible modern applications.

IGNCA also initiated two multidisciplinary projects, one in the South - the Brhadisvara temple in Tanjavur and the other in the North - the Govindadeva temple at Vrindavana with a view to examining the temple in all its dimensions: conceptual, literary, textual, historical, epigraphical, crafts traditions, ritual calendars, ritual treatises and performances. Several publications have come out as the result of these studies under a separate programme.

Coming back to the Kalasamalocana series, IGNCA has also published more works of a new line of scholars in which is observed a shift of emphasis and change of perspective on the study of temple architecture. These include Indian Temple Architecture: Form and Transformation by Adam Hardy; The Temple of Muktesvara at Caudadanapura by Vasudara Filliozat; Ellora : Concepts and Style by Carmel Berkson; Kalamukha Temples of Karnataka by Vasudara Filliozat and Pierre-Sylvain Filliozat; Lingaraja temple of Bhubaneswar by K. S. Behera - each exemplifying a new methodology of comprehending the Indian temple at the level of concept, meaning and form. IGNCA has also supported the publication of two volumes of the Encyclopedia of Indian Temple Architecture of the American Institute of Indian Studies. The Encyclopedia has come as a culminating step in the study of Indian architecture where the technical vocabulary of the texts has been applied to the architectural structure, thus fitting well into the conceptual vision of IGNCA.

In March 2011, Adam Hardy, Professor of Asian Architecture at the Welsh School of Architecture, Cardiff University, UK contacted IGNCA with a proposal of his book on "Indian Temple Architecture through Samaranganasutradhara". There were two assurances in this proposal. First, the expertise of a well known scholar in the field like Adam Hardy. Moreover, as noted above, his earlier volume on the Karnataka temples, presenting a new perspective of studying temple architecture had already been published in 1995. The second assurance was the complementarity of this proposal with the text of the Samaranganasutradhara as the critical edition with translation of this compendium on architecture was already at the final stages of completion before being processed for publication in the programme of fundamental texts. Prabhakar Apte (editor and translator) and Adam Hardy got introduced and they interacted to take the advantage of each other's expertise. Meanwhile, during his visit to India, Adam Hardy's illustrated talk on his proposal was organised in IGNCA. The talk was well attended and discussed with experts.

Finally, Adam Hardy's book is now being published as Theory and Practice of Temple Architecture in Medieval India: The Samaranganasutradhara and Bhojpur Line Drawings. This is a very significant addition to the Kalasamalocana series. Undertaken under a fresh methodology of the study of temple architecture it presents for the first time a full documentation of the Siva temple at Bhojpur and its site, in particular the engraved architectural drawings. It further explains the architectural significance of these drawings and explores their function. Explaining in detail the contents of the chapters on temple architecture in the Samaranganasutradhdra, the study presents the architectural prescriptions translated into drawings. The volume also includes the translation of substantial representative passages from the text. Further, it analyses the respective chapters in terms of their approach, organisation and argument, their linguistic peculiarities, the regional stylistic affiliation of the architecture they discuss, their relationship to actual design practice. Finally, the study substantiates and illustrates the analysis of the Samaranganasutradhara and of Bhojpur through comparison with the surviving build records. On this basis the study also reflects broadly on the processes of designing and building temples in medieval India and the relationship between such practice and theory.

Introduction

There are many questions to be answered about the Vastusastras, the 'canonical' Indian texts on architecture, and their relationship to practice.' who wrote them, priests or practitioners? who used them, connoisseurs or craftsmen? Do they seek to control practice, or to confer authority? Do they describe practice, or guide it, or inspire it? Do they aim to reveal, or partly to conceal? Do they create norms, or mnemonics? Are they an inventory of tradition, or are they inventing it?

Apart from words, architecture has another way of transmitting ideas: drawings. Were architectural drawings used in medieval India? If so, what were they like? Were they schematic or detailed, approximate or precise? Were they used to perpetuate existing principles, or develop new designs? Were they drawn to scale? Were they used for practical purposes of setting out and construction?

And how did drawings relate to the texts? Was the role of drawings diminished because so much was conveyed verbally? Or could texts only describe what had already been drawn, if not built? Are texts and drawings products of different preoccupations, one elite and the other practical? Or do both arise from a single world of complementary theory and practice?

This book may not answer all of the questions conclusively, but it brings into view material that allows them to be discussed on a more real basis than has previously been available. Focusing on the temple, the book presents the one coherent and substantial set of medieval Indian architectural drawings to have survived. These are more extensive than anything comparable from medieval Europe, and a good century earlier. 2 On the textual side, the book explores the treatment of temple architecture in the earliest truly compendious Vastusastra to have come down to us, the earliest from which recognisable temple designs can be deduced to a fair degree of detail - at least, as far northern Indian traditions are concerned. Conveniently, these drawings and this text belong to the same time and cultural nexus, to the extent that they are ascribed to the same ruler: ideal king, greatest of the Paramaras, scholar, warrior, poet, polymath, ever more legendary Bhoja of Dhar (ruled c. 1010 to 1055). The drawings lie engraved on the rocks around the giant, unfinished Siva temple (sometimes called Bhojesvara) at Bhojpur; the text is the Samaranganasutradhara of Bhojadeva, of which each chapter ends with a colophon along the following lines: The body of scholarly work specifically on the Vastusastras and Silpasastras (texts on sculpture, and crafts more generally) is not great, and is minuscule compared to all the material on vastuvidya as popularly understood ('the Indian Feng Shui'). Within this already modest corpus, illustrations have played a minor part. A remarkable exception is the very first work of modern scholarship on Indian temple architecture, the Essay on the Architecture of the Hindus by Ram Raz, published in 1834, which makes a sustained attempt to draw the contents of a Vastusastra. On the basis of fragments of south Indian texts on vastu, especially of the Manasara, and assisted by contemporary pandits and artisans, Raz had lucid drawings made, following the textual prescriptions. These were in a florid, latter-day Dravida style (1.1).3 Recent studies have focused on Raz as a 'native informant' involved in reconstructing the Indian past through the prism of the colonial project; western drawing conventions being one reflection of this situation.' This kind of analysis is important and timely, but a recognition that the past is interpreted in the light of present can blind one to the fact that it is nevertheless possible to be true to the past to a greater or lesser extent. Whatever post-enlightenment orderliness Ram Raz may have been imposing on his material, the drawings in his Essay reveal a coherence that belongs to the text in which he has found it, made visible by somebody who knows the architecture of which it speaks. This is not to suggest that there could ever be only one correct understanding of the text, but that its authors had specific building designs in mind, conceived in terms of a particular architectural language or medium, and that it is possible to grasp the nature of these designs with varying degrees of accuracy.

In Prasanna Kumar Acharya's monumental series on the Manasara, a whole volume (published in 1934) is devoted to drawings." Acharya saw the Manasara not as a south Indian text from around the tenth or eleventh century," but as the germinal text of all Indian Silpasastras. Even allowing for fact that the text at the point in question may not be differentiating temples from a general category of storeyed building, the drawings show what strange results can be obtained when interpreting these texts without understanding the architectural language (2.2) - despite a century of scholarship that had intervened since Ram Raz. An interesting contrast from the same period is the remarkable Shilparatnalear by N.M.S. Sompura,' compiled from texts and observation and taking full advantage of the published archaeological material. Published in Gujarati by an architectural practitioner, with no intention of addressing the academic world, this has detailed drawings of a full range of western Indian Nagara temple designs, and is still a prime reference for practitioners of the Sompura community today," More recent discussions of Vastu texts have regularly contained drawings of grids and mandalas, and some have reconstructed the basic layouts of house types," but plans and elevations of temples on the basis of texts have been worked out as examples rather than as comprehensive sequences. Stella Kramrisch, in The Hindu/ Temple, reconstructs three plans from the Samaranganasutradhara,'? and Bruno pagens includes two elevational diagrams in his edition of the Mayamata."

From an architectural perspective, aside from the issue of how texts and drawings were related in the medieval period, drawings are necessary as both a tool and an outcome for an adequate translation of an architectural text. In our work on the Samarangana, the verbal translation constantly had to be checked in relation to whether it worked architecturally. The forms might look wrong, or the numbers might not add up. If there were two possible readings, the one that made architectural sense would be confirmed. Certain conclusions can only be reached once designs have been drawn. For example, to establish the extent to which a particular text might have been used for creating architecture, it needs to be shown whether it can be used for this purpose, by drawing if not by actually building. Most importantly, and looking forward to some eventual conclusions, to draw from texts such as the Samarangana is to come closer to their spirit and intent. If these texts come from architecture and go towards architecture, they do so through the intermediary of drawing. The designs which they describe would have been difficult to devise and hold in the mind without drawing, and some of their dimensional and geometrical instructions relate to points that it would be impractical to locate in space, but which make sense when etched on stone or palm leaf, or simply scratched in the dust. In doing this study I have become increasingly convinced that Dagens is correct in his estimation of Vastusastra texts in general, that "most of the descriptive prescriptions are little else but written transcriptions of graphic representations. They are expressed in such a way that the architect can - must - read (or recite) and draw them at the same time."?

Contents

|

| Foreword | vii |

|

| Preface | viii |

|

| Acknowledgements | xi |

|

| Credits for the illustrations | xii |

|

| Translator's note | xii |

|

| Map showing temple sites mentioned in the text | xiii |

| 1. | Introduction |

|

|

| Temple and Text | 1 |

|

| Bhoja's Royal Temple and the Architectural Tradition | 4 |

|

| Bhoja's Treatise on Architecture and the Textual Tradition | 22 |

| 2. | Bhoja's Abandoned Building Site | 31 |

| 3. | Nagara Temples in the Samaranganasutradhara | 75 |

| 4. | Dravida Temples in the Samaranganasutradhara | 165 |

| 5. | Bhumija Temples in the Samaranganasutradhara | 203 |

| 6. | Theory and Practice |

|

|

| Bhojpur and the Samaranganasutradhara | 255 |

|

| Correlating Temples and Text | 256 |

|

| Parivartand | 260 |

|

| Texts, Drawings and the Act of Creation | 264 |

| Appendix 1. | Measured survey of the Mulaprasada of the Udayesvara temple, Udayapur, by Amita Kanekar | 271 |

| Appendix 2. | Comparisons between prescriptions in Chapter 65 of the Samaranganasutradhara and examples of Bhumija temples | 272 |

| Appendix 3. | From Point to Parivartana to Plan, by Paul Glossop | 277 |

|

| Glossary | 285 |

|

| Bibliography | 289 |

|

| Index | 292 |

Sample Pages