Towards a Nationalist Narrative of India's Ancient Past- Including Recent Research on The Indus Civilization

Book Specification

| Item Code: | UAG189 |

| Author: | Dilip K. Chakrabarti |

| Publisher: | Aryan Books International |

| Language: | English |

| Edition: | 2022 |

| ISBN: | 9788173056666 |

| Pages: | 249 |

| Cover: | HARDCOVER |

| Other Details | 9.00 X 6.00 inch |

| Weight | 460 gm |

Book Description

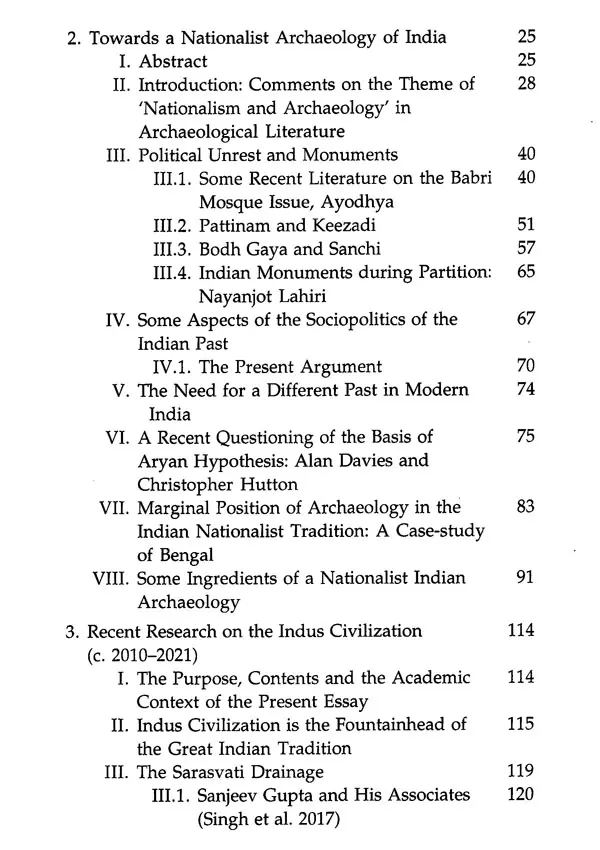

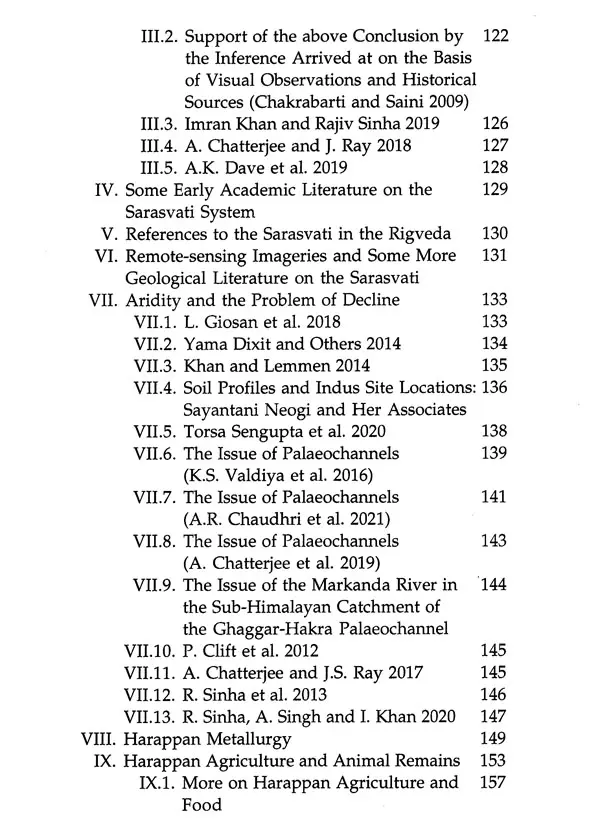

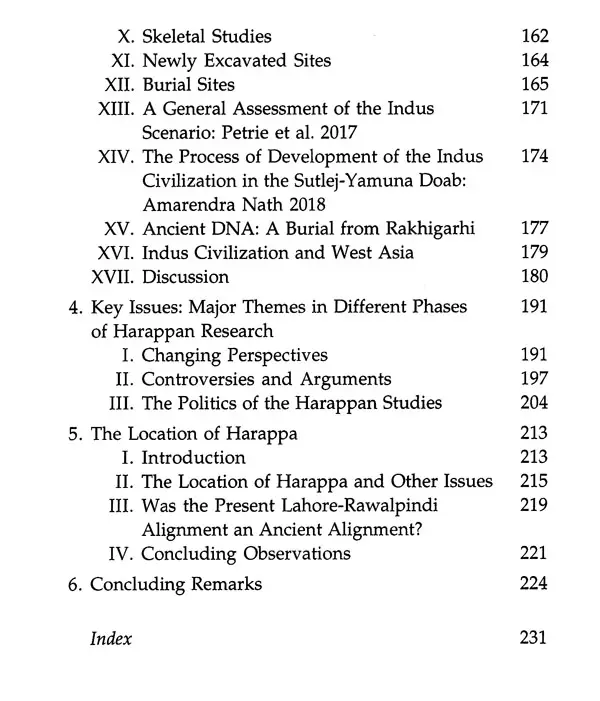

In 1966 the famous Indian parliamentarian Ram Manohar Lohia regretted in Parliament that the minds of our children were ingrained with the belief that “India had nothing of its own; everything was either imitated or influenced by outside factors”. He called the Indian historiography ‘diseased’. His opinion was echoed by M.C. Chagla, the education minister, who advocated the idea of re-writing Indian history.

Taking Dr. Lohia’s opinion as the starting point, the present volume goes on to argue that post-Independence Indian archaeologists, despite making many new discoveries, have been most unashamedly neocolonial without the least awareness of the interrelationship between archaeological data and nationalism. The volume deals with multiple aspects of this interrelationship and undertakes a critical review of the recent research on the Indus civilization, showing that the very idea of the integrity and homogeneity of this civilization, which is the fountainhead of India’s mainstream civilization, is being currently undermined by both Indian and foreign archaeologists who consider it only a veneer on top of the regional elements.

Finally, the volume argues that the geographical and chronological implications of some recent discoveries conclusively underline that India’s protohistoric archaeological column and the literary column represented by the Vedic literature are inseparably linked, thus forming the first block of the seamless narrative of India’s ancient past.

Dilip K. Chakrabarti (1941) is emeritus professor of south Asian archaeology at Cambridge University. He was awarded Padma Shri in 2019. In 2021 he received a 'life-time achievement' award from the UK Bengali Convention (UKBC).

In my Nationalism in the Study of Ancient Indian History, I pointed out how the post-Independence Indian archaeologists turned out, in the name of science, to be almost totally indifferent to the nationalistic dimensions of the study of archaeology. In claiming, as late as 1973/74 that India was always a colony, meaning thereby that all technical and cultural innovations in Indian history were derived from developments in west Asia or elsewhere, the doyen of Indian archaeologists, H.D. Sankalia, set the seal of approval on what E.J. Rapson, a Cambridge Indologist and editor of the first volume of Cambridge History of India wrote many years ago. Academically, post-Independence Indian archaeology has also been a minor underling of the discipline as practised in United Kingdom and USA. The reference point of Indian archaeology in the first two decades of the twenty-first century has continued to be the Anglo-Saxon world. Almost as a natural corollary of this situation, what has also developed among the present Western specialists in Indian archaeology is a downright racist contempt for the Indian past and the Indian scholarship in the subject. This racism is more strident than what could be traced before 1947. Western archaeologists who operated in the Indian scene before 1947 had at least some grace which was the result of long years of interaction with Indians, whereas the modern 'anthropological' and 'scientist' archaeologists suffer from no inhibition of this kind. It may also be pointed out that many of the research themes advocated by the Western archaeologists in the Indian context are irrelevant from the Indian point of view.

The present volume looks closely at this admittedly murky academic scene. It does not, however, try to offer any explanation of why archaeology in India has been so spineless and neocolonial after Independence and why it continues to be so.

This volume, written during the period of the Covid lock-down in Kolkata and Cambridge, is dedicated to the well-loved memory of a friend of mine, Shri Samir Gupta, Deputy Comptroller and Auditor General of India (Commercial). He was a friend whom I had known and grown up with since 1958.

In my Nationalism in the Study of Ancient Indian History (2021), I pointed out that for a long time after Independence it was held by professional archaeologists of India that there was no innovation except foreign intervention in technological and cultural fields in the course of the archaeological development of the country. The overall conclusion, as H.D. Sankalia put it as late as 1973 (in World Archaeology) and 1974 (in Prehistory and Protohistory in India and Pakistan), India was always a colony. In different forms the opinion persists even now, although some of its edges have become somewhat blunt because of an increasing number of early dates obtained for food-production and early copper and iron technology in the country. However, archaeological studies in India are still largely and disgustingly neocolonial in the sense that we have not yet been quite successful in offering a coherently Indian narrative for the archaeological past of our country. This does not mean that we have to glorify our past by taking recourse to outrageous claims regarding our chronology, as some people stubbornly resistant to logic or scholarship have long been trying to do. Basically, this implies a continuous and connected story of the economic and cultural developments in various parts of the land in terms of what we understand of this subcontinent as a whole and what we perceive to be intimately related to such developments. In two of my books, India - An Archaeological History (2009) and The Oxford Companion to Indian Archaeology (2006), I made such attempts but it is not for me to judge the extent to which they have been successful from this point of view.

There is another point. Have we ever tried to understand or define the basic scope or at least some of the basic nationalist dimensions of archaeology in India? The second chapter of the present volume is an attempt in this direction but in no way can this be said to be definitive. Nationalism in a country as diverse as India has to be multi-dimensional with some threads linking them together, and other archaeologists of the country, or at least those to whom nationalism as an archaeological issue matters, still have to spell out in the light of their own experience and expertise what do they mean by a frankly nationalist approach to the archaeology of the land they study.

Another issue is methodologically relevant in the present context. One of the positive features of archaeological research in modern India is the wide induction of scientific and technological expertise in the field. Scholars of different nationalities have also begun to participate in this development. However welcome such participations and the primary expansion of science-based and technology-based archaeological research are, we have to stress that all these scientific and technological data need interpretations in historical terms and it is precisely in this area that we have to be careful about how we reach these interpretations, especially when the scientists or technologists concerned have had no organized grounding in history and culture related to India or even possess any feeling of respect for the Indian past. In fact, this is an interesting situation. Anybody who can distinguish between grains of wheat and rice in the excavated record finds it almost obligatory to offer theories regarding agriculture without spending a day in the wheat or rice fields of India or having any credibility as a professional agricultural scientist. Or, somebody who can study human skeletons feels the related study incomplete unless this leads to the cause of decline of the culture, of which the studied skeletons were a part. There was a time when Bhola Nath of the Zoological Survey of India used to identify excavated animal bones in Indian archaeology but he did not consider it necessary to offer on that basis grand theoretical schemes of animal utilisation or animal domestication in ancient India. However, the academic scenario is much changed and all of us are expected to theorise to be respectable, and especially in a Third World context like India where in archaeology, or for that matter, in any branch of the humanities and social sciences, the opinion of anybody with the right skin colour and Western origin, will be the point of avid discussions.

**Contents and Sample Pages**