The Yoga of Patanjali (With an Introduction, Sanskrit Text of the Yogasutras, English Translation and Notes)

Book Specification

| Item Code: | NAC020 |

| Author: | M.R. Yardi |

| Publisher: | Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute, Pune |

| Language: | Sanskrit and English |

| Edition: | 2022 |

| ISBN: | 9788193554784 |

| Pages: | 350 |

| Cover: | Hardcover |

| Other Details | 9.0 Inch X 6.0 Inch |

| Weight | 560 gm |

Book Description

There is renewed interest in Yoga currently all over the world. The .aw of supply and demand has ensured a constant supply of courses in Yoga as a cure for the ills from which modern society is suffering. This study brings out very clearly the essentials of Yoga as explained in the Yoga sutras of Patanjali, which is the most ancient and authoritative text on the subject. The author further suggests a methodology of textual interpretation i.e. how to determine the original message of an author, when his work is overlaid by a number of commentaries and further commentaries on these commentaries. He has also made an attempt to present a historical exposition of the origin and the influence of Yoga on the other indigenous systems and vice versa.

Although there is a widespread interest in Yoga, there is very little understanding that Yoga is something more than a physical or mental drill, that it is a way of life, a preparation for the realization of one’s spiritual destiny. It is not only meant for those who are willing to take to an ascetic life, but is equally relevant to one who wishes to live a normal life as a member of society. It is an instrument for the simultaneous growth of intellect and character, which is essential for the total development of his personality. Yoga is, therefore, a method for the development of human potentialities.

Author was born in the year 1916 in a small village Supa, which is now in Karnataka State. He had the good fortune to study Sanskrit and read Bhattoji Dixit?s Sivddhanta Kaumudi with his sixth form teacher, Shri V. H. Nijsure, a Sanskrit scholar of repute, in Garud High School, Dhulia. He was awarded the Jagannath Shankarset scholarship in Sanskrit in his matriculation examination. He stood first in the first class in the BA. And MA. Examination of the then Bombay University and topped the list of successful candidates in the Indian Civil Service Competive Examination held at Delhi in 1940.

He served the then Bombay and later Maharashtra State as Collector of Poona, Dove opment Commissioner, Bombay are Finance and Planning Secretary to the Government of Maharashtra. During his stay at Nasik, he had the privilege of reading Sankara Bhasya on the Brahmasutras with His Holiness,. Kurtakoti, Sankaracarya of Karavira Peetha. He went to the Govern c of India in 1962 and held the position of Programme Advisor Planning Commission, Additional Secretary, Ministrv of home Affairs and Finance Secretary. After his retirement in 1974, he S devoting he time to the study of Yoga and Mahabharata.

There is a good deal of interest in Yoga currently all the world over for a variety of reasons. Some have taken recourse to Yoga for its therapeutic effects in curing certain nervous disorders. There is sufficient evidence to how that addicts to alcohol and drugs have benefitted from it. Some feel attracted to it because or the miraculous powers which its practice is supposed to confer. Still others coming from the affluent societies have sought after it as an antidote against a life of boredom resulting from a surfeit of comforts and self-indulgence. The law of supply and demand has ensured a constant supply of courses in Yoga, as a cure for the ills from which the modern society is suffering. There is, however, very little understanding that Yoga is something more than a physical or mental drill, that it is a method for the development of the moral and spiritual potentialities of man, While there are a few who recognize it to be a life-long pursuit of a spiritual goal, they nevertheless think that it is suitable only for those who are willing to submit themselves to a rigorous monastic life and is of no use in worldly life. This study, which has been carried on over a decade, is an attempt to understand Yoga as explained by Patanjali in the Yogasutras, which is the most ancient and authoritative text on the subject, and to examine its relevance td modern conditions. My secondary interest in this study pertains to the methodology of textual interpretation. The methods for determining the original text of an author are now well-established; but after this is done to the extent possible, what methods could we follow, to determine the author’s meaning, especially when his work is written in a sutra form and is overlaid with a number of commentaries written at different times? In the translation of Vyasa’s Bhasya, I have included only those portions which have a bearing directly on the sutras and on which there is an agreement among the commentators. This is on the assumption that the common denominator of the views of the commentators should be considered as a good approximation to the original purport of the text.

As a corollary all variations from this common denominator should be ascribed to the individual commentators and if a sufficient number of their commentaries on different texts are available, it should be possible to determine their individual contributions to the evolution of Indian philosophic thought. It is only when such studies are undertaken in respect of the important texts and their principal commentaries that it should be possible to rewrite an authoritative history of Indian philosophy.

This is a somewhat different approach from the one adopted by DASGUPTA in his monumental work, A History of Indian Philosophy. He states that it is not possible to write such a history and that all that is necessary is that “each system should be studied and interpreted in all the growth it has acquired through the successive ages of history from its conflicts with the rival systems as a whole.” He goes on to add, “It is, therefore, not possible to describe the growth of any system by treating the contributions of the individual commentators separately. This would only mean unnecessary repetition. Except when there is especially a new development, the system is to be interpreted on the basis of the joint work of the commentators treating their contribution as a whole.” 2 A historical study should, however, bring out clearly the growth of different systems over time, the individual contributions to this growth, the part played by the rival systems in critically appraising and so indirectly influencing other systems and the influence of socio-economic factors in shaping them.

Before such a study is undertaken, it is essential to determine the chronology of ancient works and their commentaries with some precision. This is rendered somewhat difficult by the lack of historical sense among the Hindus, partly compensated by the flair of the Jams and Buddhists for dates of events, pontifical and dynastic genealogies, dated colophons of their works and inscriptional records. Both the Jam and Buddhist scholars, however, usually date their authors by taking as the starting point the dates of nirvana of Lord Mahavira and Lord Buddha, which are not free from controversy. In a scholarly study, Muni Shri NAGRAJJI has established the date of nirvana of Lord Mahavira as 27 B, and that of Buddha as 502 B. C.

There are also certain landmarks in ancient Indian history such as the accession of Chandragupta Maurya (322 B. C.), the visit to India of three Chinese scholars, Fa Hem (400 A. V.), Yuan Chwang (629—654 A. D.) and It-sing (671—695 A. D.) etc. which enable us to fix the dates of some authors. For instance H. Ui has fixed the palmy days of Dharmakirti as 645—671 A. D. on the ground that he is mentioned by It-sing and not by Yuan-Chwang. This also incidentally fixes the date of Kumarilabbatta, who, according to the Tibetan tradition, was a contemporary of Dharmakfrti.1 The Chinese translations of Buddhist works also help us to establish the terminus a quo for the dates of their authors. Dignaga’s works, for instance, were translated for the first time into Chinese by Paramartha in 557—569 A. V. and so he must have lived before the end of the fifth century A. D., as he came after Vasubandhu. Again the date of an author can be determined on the basis of the critical notice taken by a contemporaneous or a later author of a rival school. For example, since Vatsyayana, the principal commentator of the Nyayasutras, criticizes the views of Ngarjuna and is in turn attacked by Dignaga, he would have to be placed before the fifth century A. D. On the other hand, similarity of ideas or even philosophical terms between two authors would not necessarily imply that they are borrowed by one author from the other. Many such philosophical terms tend concepts have come down to us from a common heritage and cannot be ascribed to a particular source. The similarities of thoughts and expressions would have to be so close as to leave no doubt that one author is quoting from another. Vysa’s criticism of Vijnanavada coupled with the close similarities of certain passages in Vyasa’s Bhasya with those in Vasubandhu’s Abhidharmakosa establishes clearly that Vyasa lived later than Vasu’s bandhu’s The above instances are given to illustrate how the chronology of ancient authors and their works can be determined by evidence collected from Jam and Buddhist sources.

Added to this problem of interpretation of the author’s meaning is the problem •of translation into a different language possessing a different syntax, different idioms and different philosophic terms having’ certain nuances of theft ‘own. It is very difficult to find appropriate words in English vocabulary to bring out the full meaning of such terms, as for instance, prakrti, purusa, avidya etc. While rendering the terra prakrti as ‘primary matter’, one has to bear in mind that in this system mind ‘is regarded as a product of matter. It would be inappropriate ‘to translate the term purusa by the word ‘soul’, as the latter has ‘a different connotation in Christian theology. Even when we use the neutral term ‘Self’ we have to remember that it has different meanings even in different indigenous systems. Similarly avidya here, although negative in form, is not the mere absence of knowledge, but denotes a positive form of knowledge which is the opposite of true knowledge.’ Wood’s translation of avidya as ‘undifferentiated knowledge” is not likely to be intelligible to anyone who does not know that avidya or knowledge in this system is discriminating knowledge between the Sell and primary matter, and avidya is just the opposite, namely undifferentiated knowledge between the two. In order to bring out this positive aspect of avidya, the term has been translated as ‘error’, to distinguish it from ‘ ignorance ‘ or ‘ nescience’, which is mere absence of true knowledge. A glossary of yogic terms has been appended, in which an attempt has been made to explain these terms.

As regards translation of a Sanskrit text into English or for that matter into any other language, one has to make the difficult choice between making it too literal and making it readable. The’ traditional method favours literal translation of the text, word by word, in which the missing verb or word is supplied in parenthesis. This made the translation too involved, clumsy and often unintelligible. In translating from, one language into another, the peculiarities of a syntax and idiom of both the languages have to be given due consideration. For instance, in English the sentence’ is never complete without a finite verb, but in Sanskrit the verb is often skipped, or used in its nominal or adjectival form. In translating into English, therefore, the missing verb has to be supplied. Where, however, the verb is expressed in its nominal form as in drastuh avasthanam’ or its adjectival form as in viksepasahabhuvah,’ it is simpler to translate them as the ‘Self abides’ and accompany distractions’ respectively. Again Sanskrit has no equivalent of the English verb ‘to have’, the thing possessed being put in the nominative case and the possessor in the genitive. Thus cittasya ekagrataparjnama’ could be translated simply as ‘the mind has the modification of one-pointedness. Further Sanskrit prefers the passive voice to the active, so much so that the use of impersonal passive with an intransitive verb is also permitted as in isvarena bhuyate, God exists. Lastly Sanskrit uses compounds (samasa), which in moderate forms combine beauty of expression with brevity of form. These have to be translated in forms appropriate to the English language. Subject to these observations, care has been taken to see that the translation of the Yogasutras and Vyasa’s Bhasya has been kept as close to the text as possible according to the commonly accepted interpretation of the commentators.

Acknowledgments

I am greatly indebted to my former Professor, Dr. R, N. DANDEKAK, for making many helpful suggestions and for accepting this book for publication in the Bhandarkar Oriental Series. My thanks are also due to Shri V. L. MANJUL and Shri A. N. GOKIIALE of the Bhandarkar Oriental Research institute for correcting (lie proofs.

1. Importance of the Work

The Yoga system has been traditionally accorded a well- deserved place among the six systems (sad darsanas) of ancient Hindu Philosophy. Patanjali's Yogasistras, which is the most ancient text on the Yoga system, is historically important for two reasons. Firstly it provides a connecting link between the theistic forms of Upanisadic thought and their later development into the doctrines of Ramanuja, Nimbarka, and Madhva. Secondly, it forms 'a bridge between the philosophy of ancient India and the fully developed Indian Buddhism and the religious thought of today in Eastern Asia ', The Sankhya Yoga system can legitimately take credit for the discovery that the material universe is the result of an evolutionary process and all physical and mental phenomena are the products of primary matter or what may be more appropriately termed the world-stuff (prakrti). The special contribution of the Yoga system, however, which is relevant to the modern times, is its analysis of the conscious, unconscious and the super-conscious states of mind and the forging of a method for the intellectual and moral development of man.

2. Date and Text

Although Patanjali has long been known as the celebrated author of the Yogasutras, we have very little' knowledge about him. It is also not possible to state with any certainty whether he is the same as the author of the Mahabhasya, the great commentary on Panini's grammar. As WOODS has ably argued, these two great works exhibit divergences of philosophical concepts and terminology and that the tradition of their common authorship is also of a late origin. This, together with the absence of a corresponding tradition among the grammarians, raises serious doubts regarding the identity of the; two The uncertainty regarding the date of the Yogasutras is still greater. JACOBI's arguments for ascribing a later date to the Yogasutras are inconclusive. The evidence so painstakingly collected by WOODS and the arguments advanced by him to fix the date of Yogasutras somewhere between 400 A.D. and 500 A.D. are more relevant for fixing the date of the Yogabhasya of Vysa.1. Although the Yogasutras discloses an acquaintance with the basic tenets of early Buddhism, there is little evidence to show that Patanjali was aware of the sunyavada of Nagarjuna' or the vijnanavada of Asanga and Vasubandhu. On the other hand, Nagarjuna mentions the Sankhya (Kapila), the Yoga and the Vaisesika in his Dasa-bhumi-vibhasa-sastra. His disciple Aryadeva mentions in his CatuhSataka the four wrong impressions, which Correspond closely with the fourfold nature of avidya described in the Yogasutras. We find very close similarities of thought and expression between the Yogasutras and Tattvarthadhigamasutra of Umasvati and find a mention of the Yogasutras on yamas and niyamas 'in Umasvati's own Bhasya on Tattvarthadhigamasutra, Yoga is further mentioned in the Vaisesikasutras of Kanada3 and the Nyayasutras of Aksapada." Badarayana's refutation of Yoga in the Brahmasutras5 seems to have been intended for Patanjali'. Yoga. It is probable that Patanjali lived prior to Nagarjuna, Aksapada and Badarayana, and was a senior contemporary of Umasvati, who flourished in the first century A.D.5

The Yogasutras, as the title suggests, has been written in the aphoristic style. This form of composition was adopted in the days when all knowledge was transmitted from the teacher to the disciple by word of mouth and so had to be committed to memory. The sutras (lit. threads) are short and pregnant half- sentences which serve to hold before the reader the lost thread of memory of the elaborate disquisitions" of his teacher. The sutras must be concise, unambiguous, meaningful, comprehensive, devoid of superfluous words and faultless.1 As the text of the Yogasutras has been written in the sutra style, it has come down to us well-preserved and, without any additions or significant alterations. The most carefully edited text is the one published in the Anandashrama Series, which contains in addition to the commentaries of Vyasa and Vacespati, the independent gloss of Bhoja. Another carefully edited text is the one in the Bombay Sanskrit Series by Rajaram Shastri BODAS. I have adopted the text printed in the Anandashrama Series which contains the commentaries of Vyasa and Vacaspati and have used the text in the Kashi Sanskrit Series for the commentaries of Raghavananda Sarasvati, Vijnana Bhiksu and Hariharananda Aranya. I have also consulted the text in the Chowkhamba Sanskrit Series, which contains the commentaries Sutrarthabodhini and Yogasiddhanta- candrika by Swami Narayanatirtha and the text printed by the Nirnayasagara Press, Bombay, with the vrttis of Bhavaganesa and Nagojibhatta.

| Preface | iii | |

| Scheme of Transliteration | xi | |

| List of Abbreviations | xii | |

| Introduction | 1 | |

| Yogasutras First Part: On Contemplation | ||

| I | What is Yoga | 116 |

| II | Classification of Mental States | 119 |

| III | Two Planks of Yoga | 124 |

| IV | Kinds of Samadhi | 127 |

| V | The Attributes of God | 132 |

| VI | Obstacles and Purificatory Action | 136 |

| VII | Four Kinds of Conscious Contemplation | 143 |

| VIII | Contemplative Insight | 150 |

| IX | Superconscious Contemplation | 152 |

| Second Part: On Aids to Yoga | ||

| X | Yoga of Action | 154 |

| XI | The Affiliations | 155 |

| XII | The Deposit of Action | 162 |

| XIII | Four Divisions of Yoga | 169 |

| XIV | Aids to Yoga | 184 |

| Third Part: On Miraculous Powers | ||

| XV | Aids to Yoga (contd.) | 200 |

| XVI | Concentration (Samyama) | 201 |

| XVII | Modifications of Quality, Limitation and Condition | 203 |

| XVIII | Nature of a Substrate | 207 |

| XIX | Miraculous Powers | 210 |

| Fourth Part: On Isolation | ||

| XX | Sources of Supernormal Powers | 236 |

| XXI | Four Kinds of Karma | 239 |

| XXII | Subconscious Tendencies | 239 |

| XXIII | Reality of External Objects | 244 |

| XXIV | Self and the mind | 247 |

| XXV | The Characteristics of an Adept | 252 |

| XXVI | Liberation | 255 |

| Notes | ||

| A. | The Authorship and Date of the Yogasutras | 259 |

| B. | Three Principal Commentators of Yogasutras Vyasa, Vacaspati and Vijnana Bhiksu | 265 |

| C. | Refutation of Some, Buddhist Doctrines by Vyasa and Vacaspati | 274 |

| D. | Sankhya Teachers mentioned or quoted by Vyasa | 293 |

| E. | Some Nyaya-Vaisesika Doctrines as contrasted with Sankhya-Yoga Doctrines. | 297 |

| F. | The Sphota Theory | 300 |

| G. | The Seven Worlds | 308 |

| Select Bibliography | 312 | |

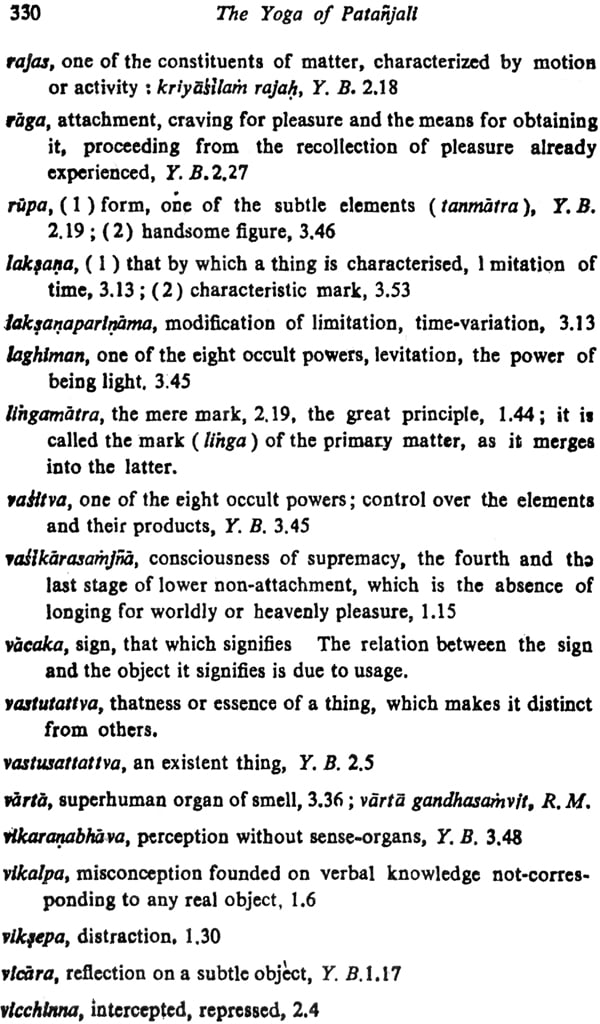

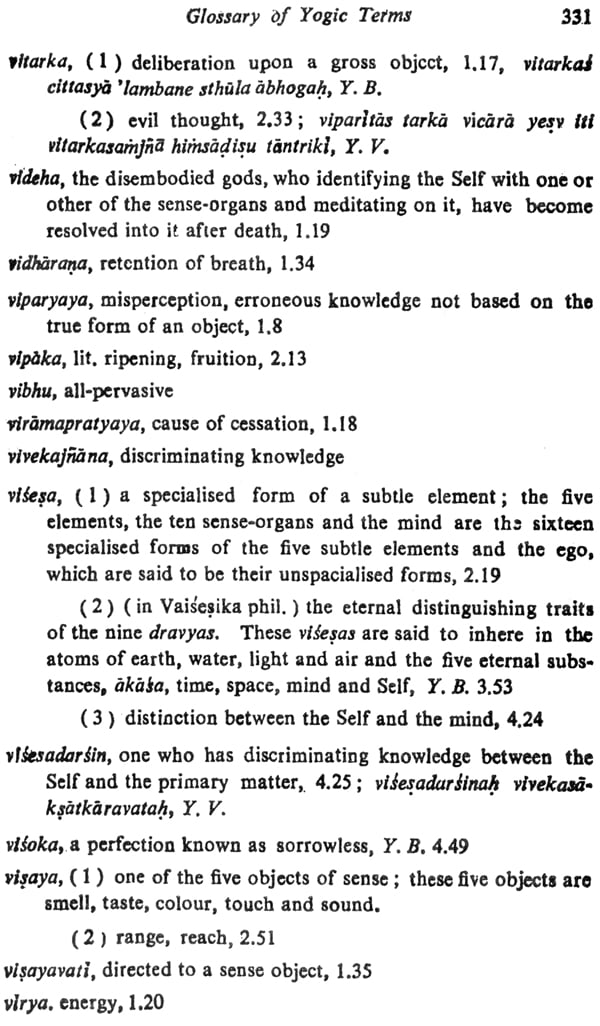

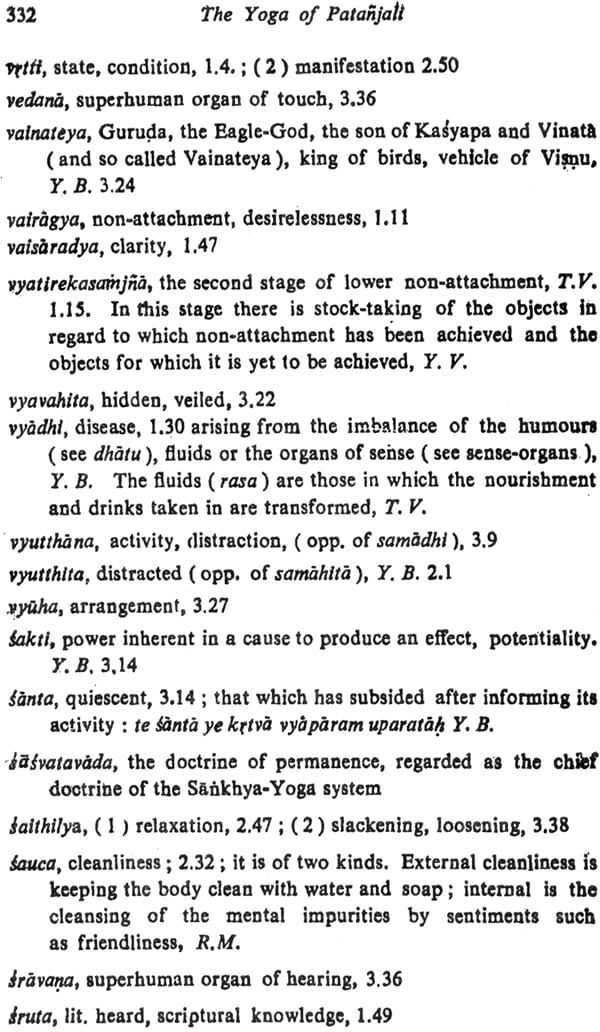

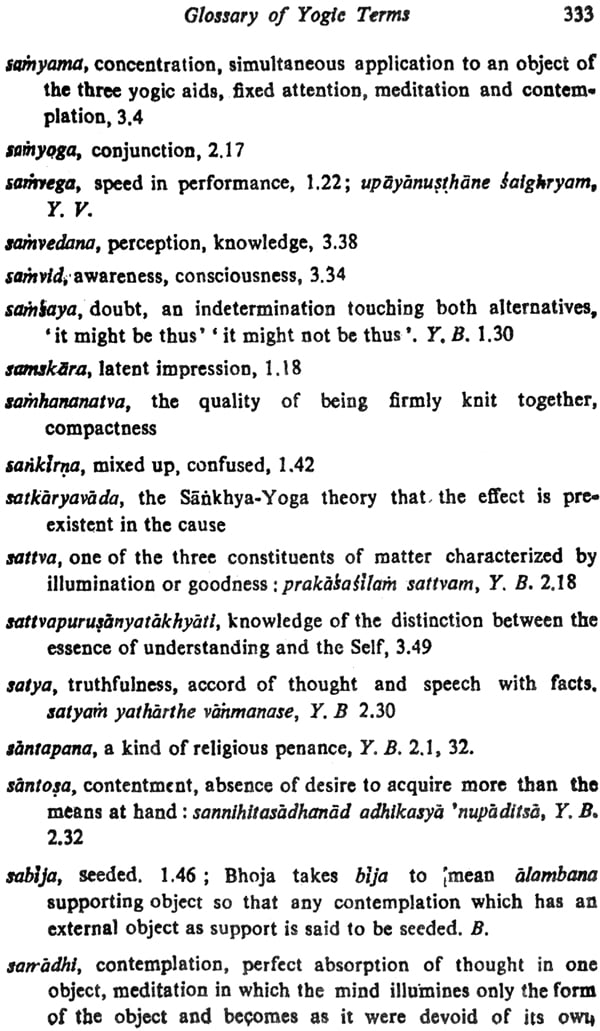

| Glossary of yogic Terms | 315 | |

| Index | 336 |