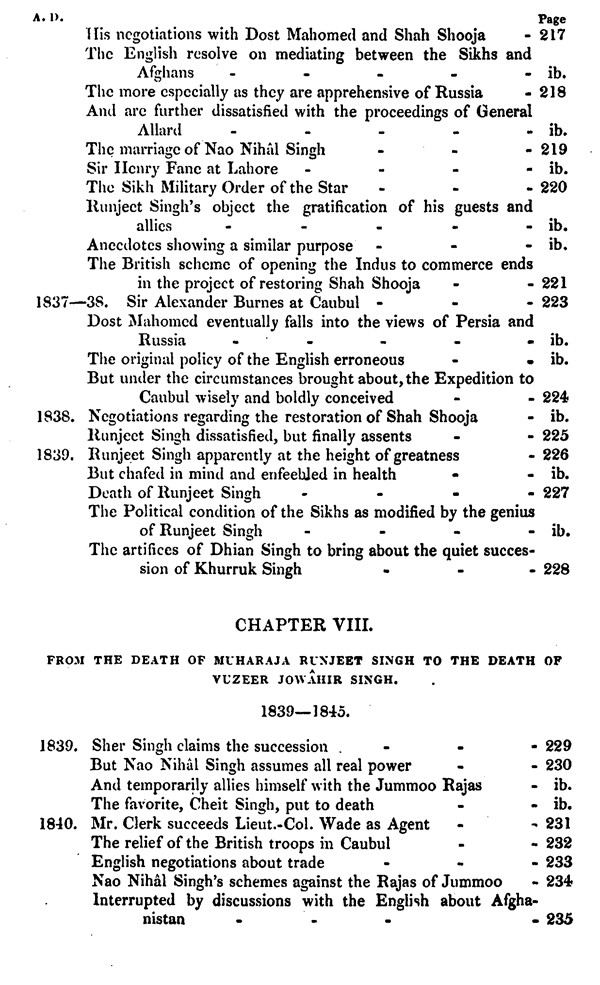

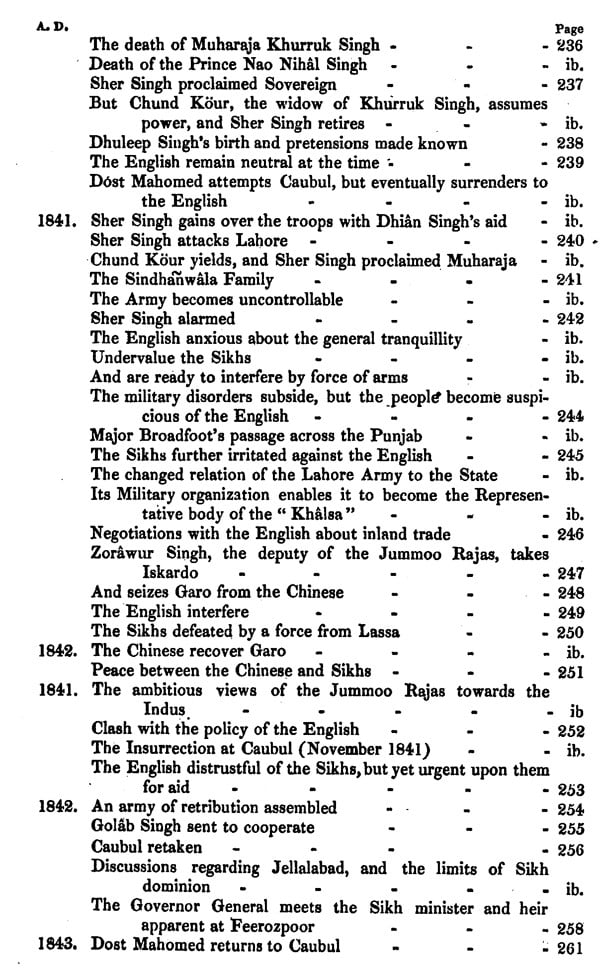

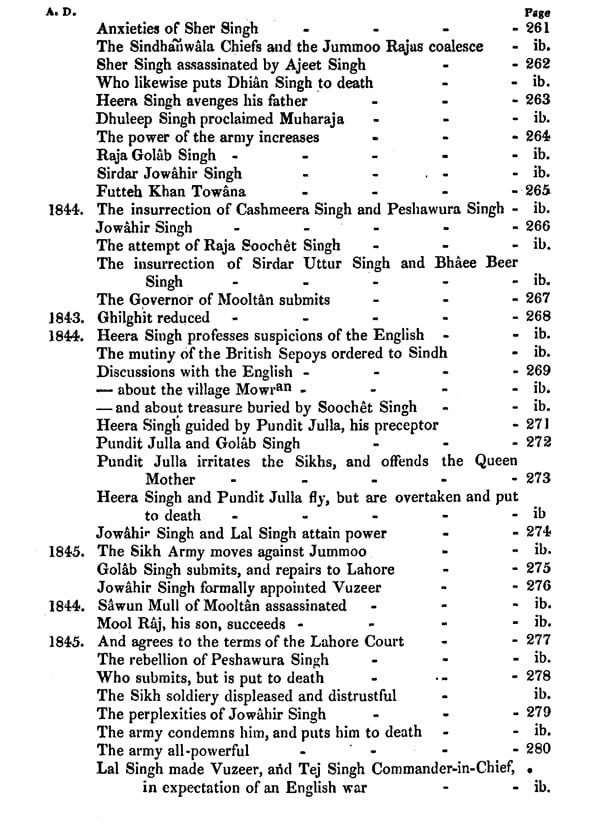

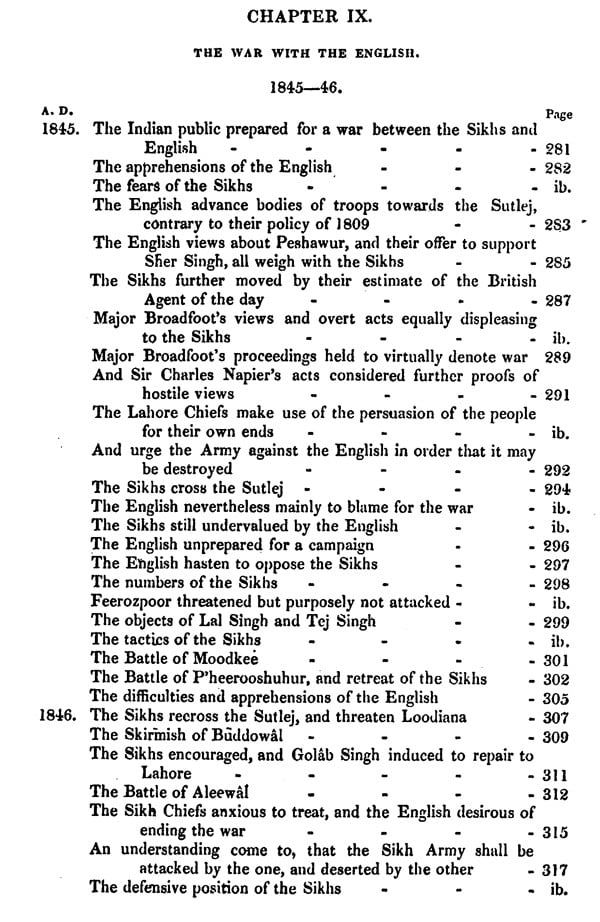

History of The Sikhs

Book Specification

| Item Code: | UAB063 |

| Author: | Joseph Davey Cunningham |

| Publisher: | Rupa Publication Pvt. Ltd. |

| Language: | English |

| Edition: | 2021 |

| ISBN: | 9788171677641 |

| Pages: | 474 |

| Cover: | PAPERBACK |

| Other Details | 8.50 X 5.50 inches |

| Weight | 460 gm |

Book Description

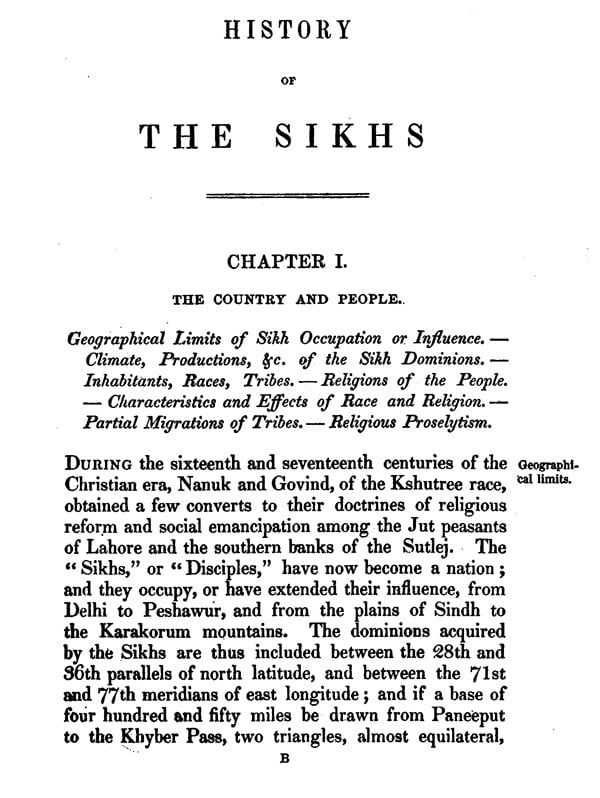

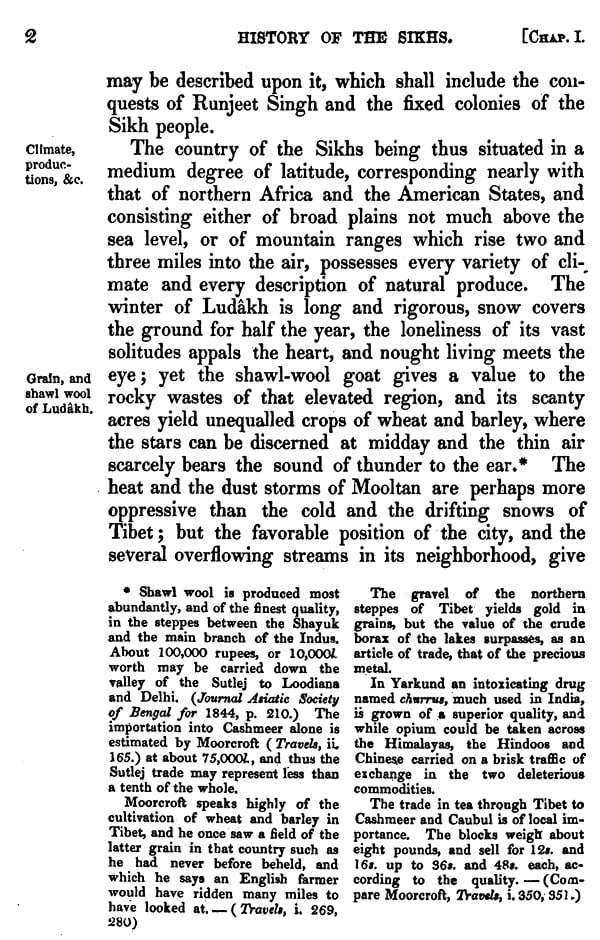

In the History of the Sikhs, the author not only provides fascinating details about the Sikhs but also displays his penchant for minute observation on subjects as varied as saffron and shawls of Cashmeer (Kashmir) and the Dogras and Kunnets of the Himalayas.

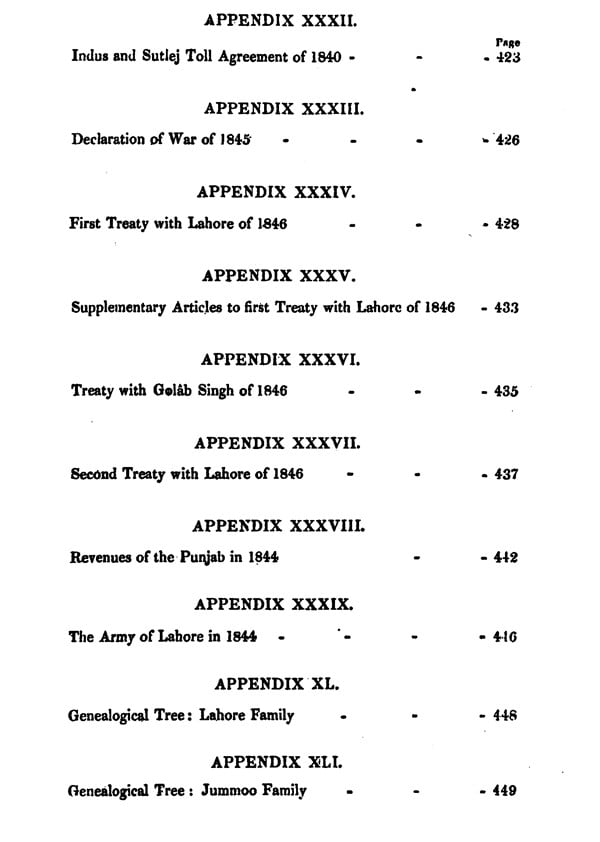

The book traces the birth and rise of Sikhism, and records Punjab's history in the context of the geopolitical situation prevalent in the nineteenth century. Of equal interest are the footnotes, notes and appendices that provide details of historic treaties as well as translations of the wonderful poetic renderings of the Sikh Gurus.

I consider it an inspired idea to republish this book which first appeared 153 years ago! Especially as it is no ordinary book. Written by an exceptional person of deep convictions and the courage to express them, the author "fell a victim to the truth related in" it. He had to pay a heavy price for his integrity.

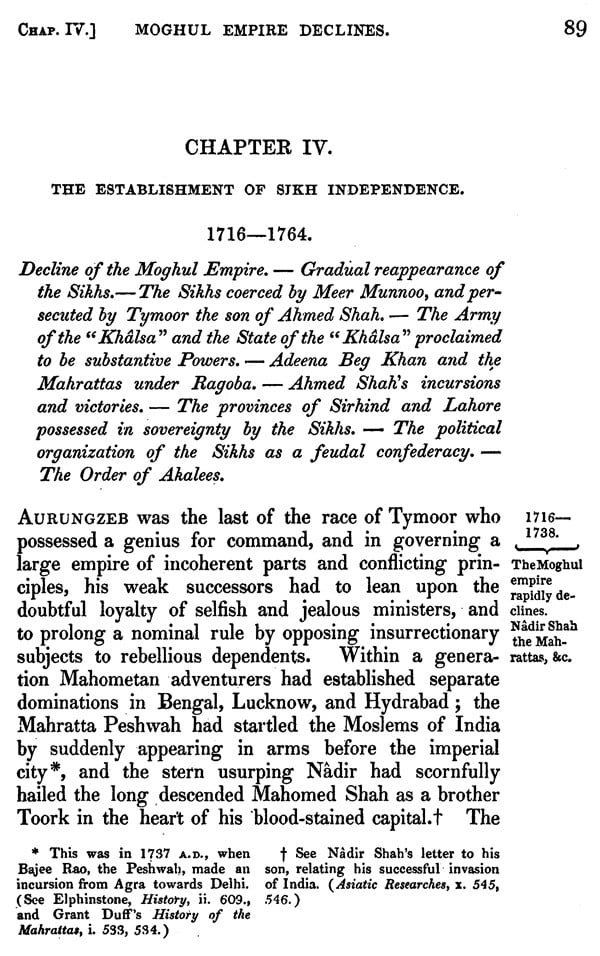

Starting his career as an officer in the army of the East India Company, Joseph Davey Cunningham became an aide to Colonel Claude Wade, political agent at Ludhiana, in 1837, in-charge both of British relations with the Sikh Kingdom, and the rulers of Afghanistan. Within his tragically short lifespan of 39 years, Cunningham rose rapidly in the political service to which he was opted. He was British Agent in Bahawalpur State at the start of the First Anglo-Sikh War in 1845-when he was recalled by the army and placed on the staff of Sir Charles Napier, then moved to the Army Chief, Sir Hugh Gough's headquarters in Ambala, before becoming an aide-de-camp to the Governor. General, Sir Henry Hardinge, who had also moved to Ambala in 1845 in anticipation of the impending war. This was six years after the legendary Sikh ruler Maharaja Ranjit Singh's death in 1839.

These men, many of whom would carry out the Company's aim of subverting and eventually annexing the Sikh Empire after Ranjit Singh's death, chose Cunningham for very good reasons. Having lived for years with the Sikhs and observed them close-hand, and been present at the 1838 meeting between Maharaja Ranjit Singh and Lord Auckland the then Governor-General, Cunningham was considered the right choice for interpreting the attitudes of "the Sikhs, as the leaders of a congenial mental change" in India. But Hastings and others hadn't reckoned on the objectivity with which he would view Anglo-Sikh relations, nor his respect for the Sikh faith, character, courage, and code of personal conduct.

He wrote this book on the Sikhs because he wished "to give Sikhism its place in the general history of humanity," even though it is difficult for minds rooted in different cultures to write with credibility on the convictions and beliefs of distant civilizations. Cunningham did it. He also placed in perspective "the connection of the English with the Sikhs, and in part with the Afghans, from the time they began to take a direct interest in the affairs of those races, and to involve them in the web of their [the English] policy for opening the navigation of the Indus, and for bringing Toorkistan and Khorassan within their commercial influence." How fascinating that these oil-rich regions of Central Asia-whose natural resources the world is eying with undisguised greed today-were already coveted by the British over 150 years ago!

Peter Cunningham, the author's brother, rightly observed in the preface to the second edition published in January 1853 after Joseph Davey Cunningham's death, that, "History, to be of any value, should be written by one superior to the influences of private or personal feelings", and added that "truth alone influenced the mind and guided the pen" of his brother. But since the 'truth' Cunningham had to tell was not to the liking of Hastings and others, they punished him for revealing the unsavoury acts which helped the British win the First Anglo-Sikh War. As becomes clear in this book, the war was not won by valour but by treachery and deceit, which included bribing the adversary's top commanders to betray their side. The three traitors responsible for betraying the Sikh Kingdom were the Jammu Dogra, Gulab Singh, and the two Brahmins, Lal Singh and Teja Singh. After the canny British had correctly assessed their perfidious bent, they were assiduously encouraged to betray the Lahore Darbar. But how did these men occupy such key positions in the Darbar? While consolidating his hold on Punjab, Ranjit Singh had elevated many non-Sikhs to high office. Since Sikhs accounted for only 7 per cent of the population in which Muslims were over 50 per cent and Hindus around 42 per cent, he secured the loyalty and support of all by refusing to discriminate against them in the governance of his kingdom. He kept them in line during his lifetime, but the intrigues, betrayals and tragedies which followed his death, resulted in Lal Singh becoming Prime Minister, and Teja Singh the Commander-in-Chief of the Sikh army. Gulab Singh bided his time, using it well to amass immense wealth. Since his aspirations too left little room for pangs of conscience, his rewards would soon exceed his wildest expectations.

It is no coincidence that within weeks of Lal Singh and Teja Singh's elevation to the top positions in November 1845, the British Governor-General declared war on the Lahore Darbar on 13 December 1845. The provocation for precipitating the war was conveniently provided by a Major Broadfoot. The Sikh army, as Cunningham puts it, need "not have heeded the insidious exhortations of such mercenary men as Lal Singh and Tej Singh," but these two were paid by the British to keep them informed of their military plans, and deflect the Sikh army away from where the English were at their weakest. They were most vulnerable in Ferozepur, yet, according to Cunningham, "no attack was made upon its seven thousand defenders...[because] the object, indeed, of Lal Singh and Tej Singh was not to compromise themselves with the English by destroying an isolated division...Their desire was to be upheld as the ministers of a dependent Kingdom by grateful conquerors, and they...assured the local British authorities of their secret and efficient goodwill."

In the subsequent battle of Ferozeshahr: "The confident English," writes Cunningham, "had at last got the field they wanted...[but] the resistance met was wholly unexpected...Guns were dismounted, and their ammunition was blown into the air; squadrons were checked in mid career; battalion after battalion was hurled back with shattered ranks...the obstinacy of the contest threw the English into confusion; men of all regiments and arms were mixed together...colonels knew not what had become of the regiments they commanded or of the army of which they formed a part...On that memorable night the English were hardly masters of the ground on which they stood."

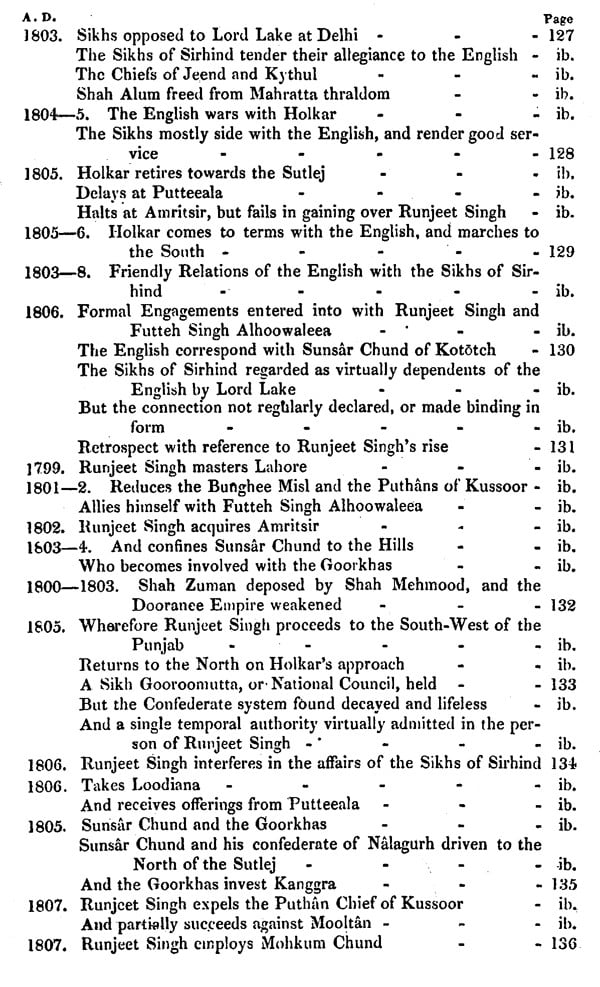

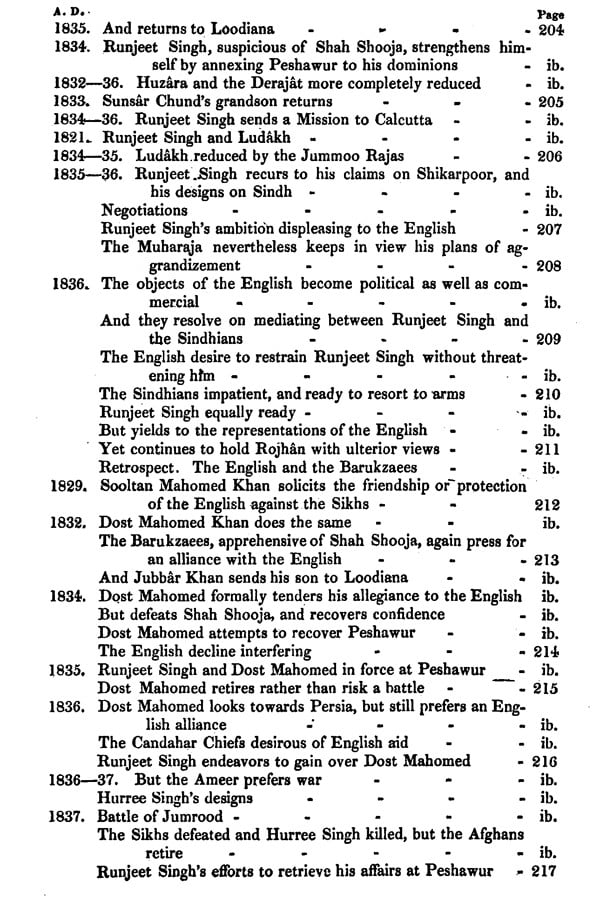

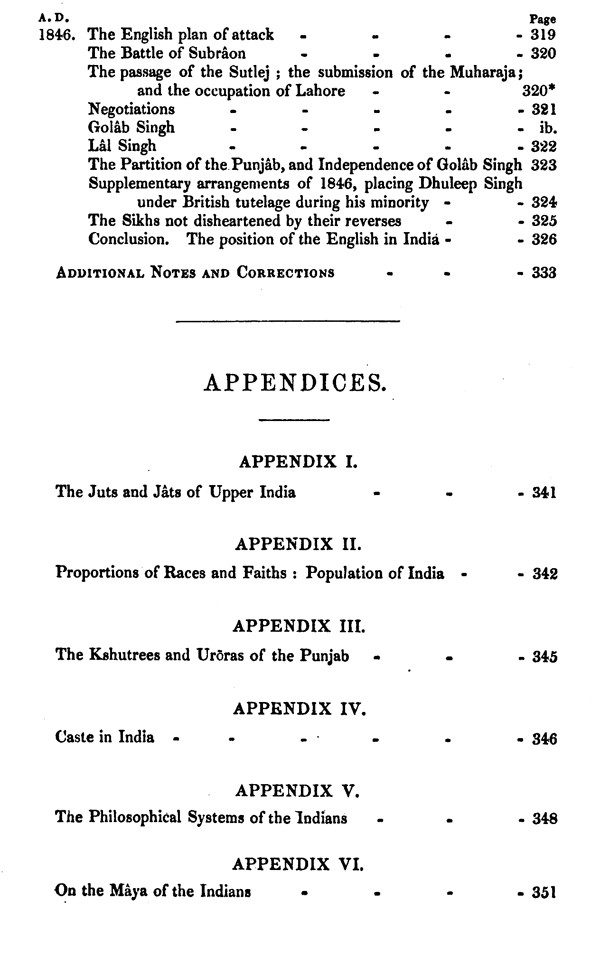

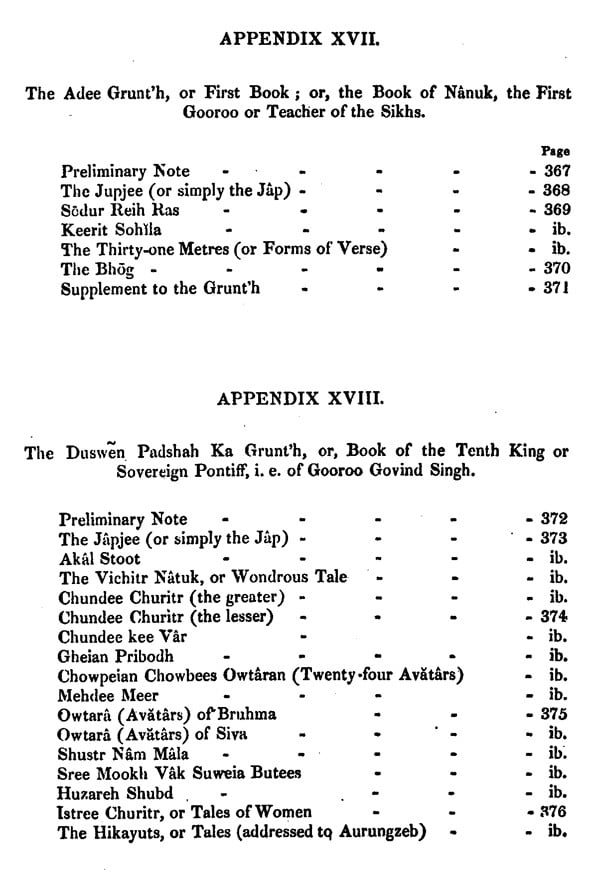

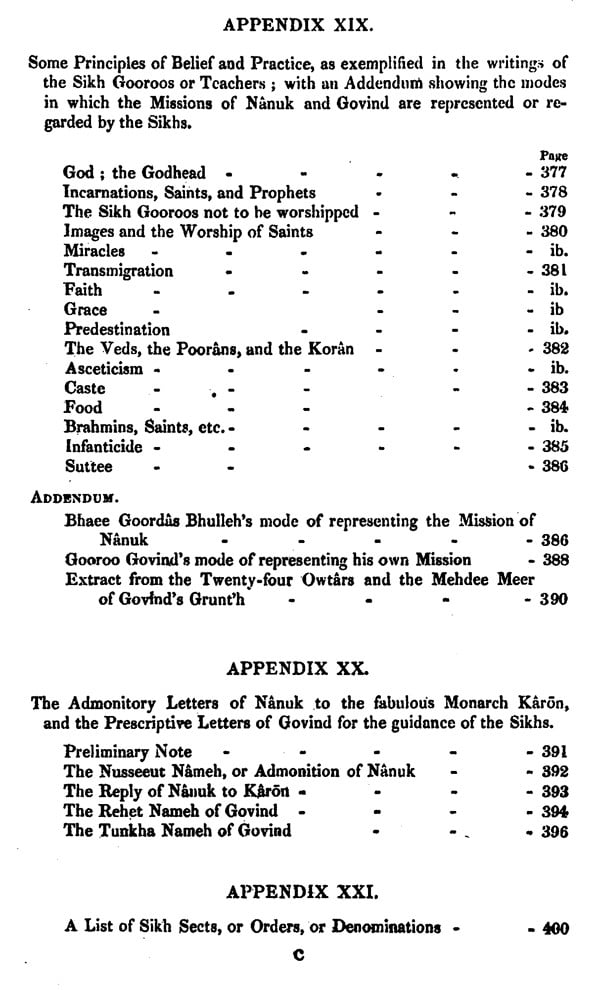

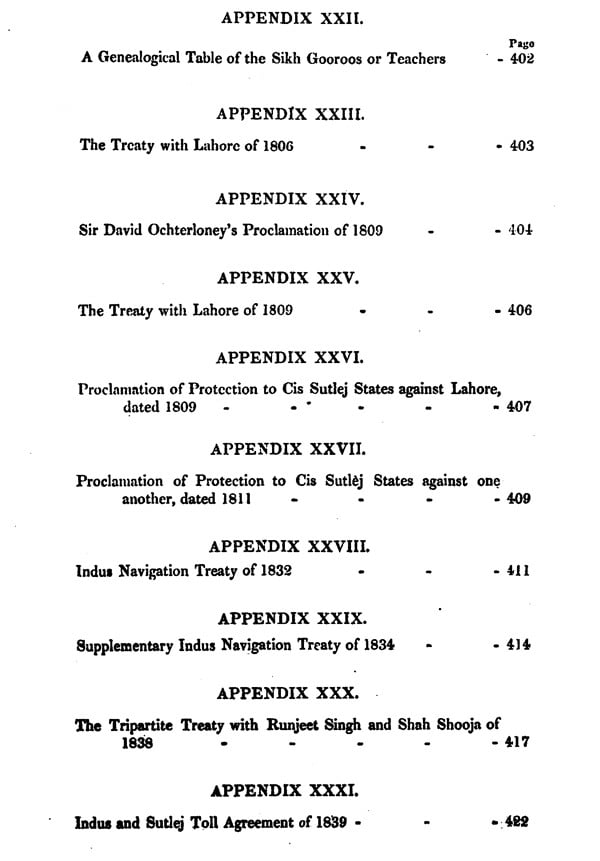

**Contents and Sample Pages**