Tense, Aspect, and Mood in English and Marathi

Book Specification

| Item Code: | NAM133 |

| Author: | Ramesh Vaman Dhongde |

| Publisher: | Deccan College Postgraduate and Research Institute |

| Language: | English |

| Pages: | 493 |

| Cover: | Paperback |

| Other Details | 8.5 inch x 5.5 inch |

| Weight | 740 gm |

Book Description

I have often been startled by the keen observation, deep insight, and a very good sense of humour in English Linguistics and have wondered if there could be such Linguistics in Marathi also. Since I began to study Linguistics, I was eager to apply its findings to Marathi. The present survey is one of my attempts at it. As I was a teacher of English at the time when I was working on this topic, I thought a comparison of the two languages would also be fruitful. But the book is by no means a contrastive analysis of English and Marathi.

The book is a slightly revised version of my Ph. D. dissertation submitted in 1974. I am grateful to Dr. Ashok R. Kelkar not only for his guidance-which, I am aware, very few students of Linguistics are fortunate to get-, or his patience with me, but specially for the long continued discussions we have had which broadened my comprehension and made me aware of my limits. In revision I have not altered the basic scheme-I do not think it is necessary to do so. I have added examples, especially from Marathi. I thank my wife, members of my family and my friends for scrutinizing many utterances in Marathi.

I always felt that my thesis should go in print and had always felt it to be impossible because of its bulk. I am extremely grateful to Dr. S.B. Deo, Director of the Deccan College Postgraduate and Research Institute, Dr. M.K. Dhavalikar, Chairman of the Publication Committee, and Dr. P. Bhaskararao, Head of the Department of Linguistics, Deccan College for encouraging me in this work and making an impossible thing possible. Without their help my work would have sunk into oblivion.

I am happy to publish Dr. R.V. Dhongde’s “Tense, Aspect, and Mood in English and Marathi’ which, I am sure, researchers in Linguistics would welcome. The book’s originality and thoroughness were admired by his referes and though delayed, its publication will be beneficial for students of Linguistics. The institution has always published outstanding works of scholars-this book is a continuation of that tradition. I am aware of the hard work Dr. Dhongde had to put in producing this work and am sure that he would produce such works in future.

The aim of the present survey of the temporal, the aspectual, and the modal notions and their formal expression in English and Marathi is a very humble one, Up to this time many grammarians like Jespersen, Sweet, Poustma, Curme, and a neo-traditional like Hatcher, linguists like Joos, Diver, Twaddell, Halliday, Huddleston, Crystal, Binnick, Jacobson, Robin Lakoff, Ehrman, and many others- who are listed in the Bibliography-have tried to tackle the problem, with reference to English. We will, of course, take into account the invaluable insights provided by them. At the same time, we will try to establish our own framework.

One noteworthy thing about the earlier treatments of English verb inflection and phrases and modal verbs is that the problem is considered either from the formal side or from the side of meaning. And each side criticises the other by pointing out the failures in correlating the two. We have tried to establish the formal mechanisms for English and Marathi in Chapter 1 and to propose a framework of the notional categories in Chapter 2. The establishment of the notional framework, for us, is a challenge, since we are always in the danger of being fools to rush in. But even if this survey makes one aware that Tense, Aspect, and Modal systems cannot be considered without a systematic approach to their meaning part, the aim of this survey will have been achieved. The second aim of this survey is to dispel an assumption that the way from form to meaning or vice versa is a simple, direct way. And this is where the importance of Chapter 3 comes, in which we have taken a survey of relevant conditions necessary for interpreting a given form or expressing a given notion. Almost every Tense or Aspect marker or a Modal verb has different interpretations in different conditions. Again the formal expressions of Time, Aspect, and Mood are entangled with each other. Many previous treatments of Tense, Aspect, or Mood suffer from their decision to confine themselves to one of the three or even to a part of one of the three. The global approach here puts us in a better position to watch and consider the disputes among linguists with interest and understanding.

Chapters 4 and 5 seek to realize our third aim. Given a form, one must be able to find its meaning with the help of our analysis and given a string of notions one must be able to find a proper expression for it. The possible number of formal specifications of the constituent AUX in a sentence in a given natural language is large but finite and hence one entertain some hope of exhausting the domain by offering possible interpretations of those forms. But one cannot make such a claim in respect of the number of notions a language can express. We must be aware of our limits in this respect. Neither do we claim to exhaust nor do we aim at exhausting all the notions related to Tense, Aspect, and Modal systems. Rather we cover such notions as are responsible for some formal distinction at some point if not consistently so.

Our fourth aim is to see what emerges out of the non-historical comparison of the Tense, Aspect, and Modal systems of English and Marathi. The comparison may have three advantages. One it might throw some light on language universals. Second, it will serve to bring out the peculiarities of the two languages. Finally, it will give us better equipment for establishing translation rules between English and Marathi, for identifying teaching points in teaching English to Marathi speakers and vice versa, and for understanding better the mechanisms underlying deviations of tense, aspect, and modals in the English as used by Marathi speakers. Such a comparison is therefore going to be of some practical use. However, a detailed working out of translation rules, contrastive analysis, and error analysis is outside the scope of this study.

And our fifth and final aim is to contribute something to the study of linguistics-especially to the study of Marathi linguistics. No major work has been done after Dr. Kelkar’s exhaustive and exhausting analysis of Marathi Phonology and Morphology. In spite of (perhaps I should say, in view of) the complaints that Marathi is a messy language-which can be seen by reading part B of Chapter 1 alone-its study is worthwhile. The intimate study of modern Indian languages by linguists speaking them natively is an urgent need.

While we have made every attempt to present a reasonably adequate picture of the formal and the notional systems taken by themselves, our primary aim is rather to establish correlations-what we call Expression Rules in Chapter 4 and Interpretation Rules in Chapter 5. And therefore, we are not over ambitious in making either the formal system or the notional system rigorous and compact. As a result the analysis offered in Chapter 1 is more of a surface analysis than a deep one. In Chapter 2 also where we deal with notions and diagnostic tests we have followed principles of logic. But that is also as far as it is convenient to our main purpose. We are not trying to generate notional strings. For example, we have not cared to find why there is no back-linking Narrative Cohesion between sentences is Marathi and English, though it is logically possible (‘and earlier’ replacing the story-teller’s ‘and then’). We feel that establishing rules for generating notional strings for Time, Aspect, and Mood will be premature at the present stage of our understanding. In short we heartily endorse Robin Lakoff’(1970) slogans ‘A Perfect Mystery at Present’, ‘the Future is Just as Dark’, and ‘Things are Tough Allover’.

In the sections entitled ‘Discussion’ at the end of Chapters 1 to 5, we have acknowledged our debt to linguists and grammarians from whom we have drawn a lot of ideas. But there our acknowledgement is restricted by the relevant topic of discussion. The bibliography given at the end, therefore should not be considered only as a list of authors who have worked on the same problem but also as a list of authors who are our secondary sources. Being a non-native speaker of English the author of this survey has drawn, as far as possible, English examples from naive native-speakers or native- speaking analysts. We have quoted at the end of some sentences the names of those who have cited them earlier. Other sentences are checked with the help of some native speakers. In the case of Marathi the author mainly depends on his own idiolect though he has taken help of other when he was in doubt. It is hoped that, though this or that example may be disputed, a fair amount of observational and descriptive adequacy has been achieved.

We have not followed any right method of analysis. We are neither strictly transformationist nor systemic or structuralist. We have collected insights and data from all and tried to put it in some form. The analysis is more data-oriented than mosel-oriented. It is hoped that the result is the evolvement of a somewhat new analysis. As we have already indicated, the grammar of Chapter 1 is basically a grammar of forms and therefore nearer the surface than the grammar as proposed by, say, generative semanticists. The accompanying diagram should indicate the framework implied in the present attempt. We have frankly left out any attempt to set up a mechanism for generating notional strings which can be the input for expression rules. Basically, the output of interpretation rules is the same as the input of expression rules. In the actual process of analysis tentative versions of both types of rules were framed at the same time with extensive cross-comparison, and constant revision. This does not imply, however, that expression rules and interpretation rules are simple mirror images of each other. If thay were, it would of course be trivial to two sets of rules.

| Preface | vii-viii | |

| Foreword | ix | |

| Contents | xi-xv | |

| 0 | Introduction | 1-14 |

| 1 | Survey of Available Verbaal Forms | 15-97 |

| 1 A | English | |

| 1 B | Marathi | 48-94 |

| 1 C | Discussion | 94-97 |

| 2 | Survey of Expressible Notional Categories | 98-143 |

| 2 A | Fremework | 99-140 |

| 2 B | Discussion | 140-143 |

| 3 | Survey of Relevant Conditions | 144-193 |

| 3 A | A English | 144-165 |

| 3 B | Marathi | 165-189 |

| 3 C | Discussion | 189-193 |

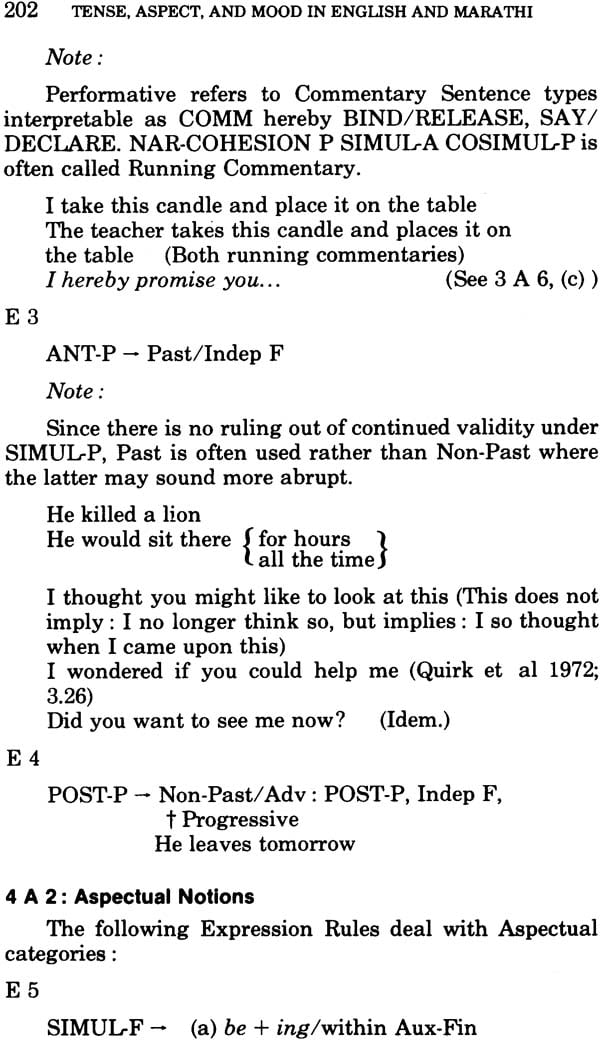

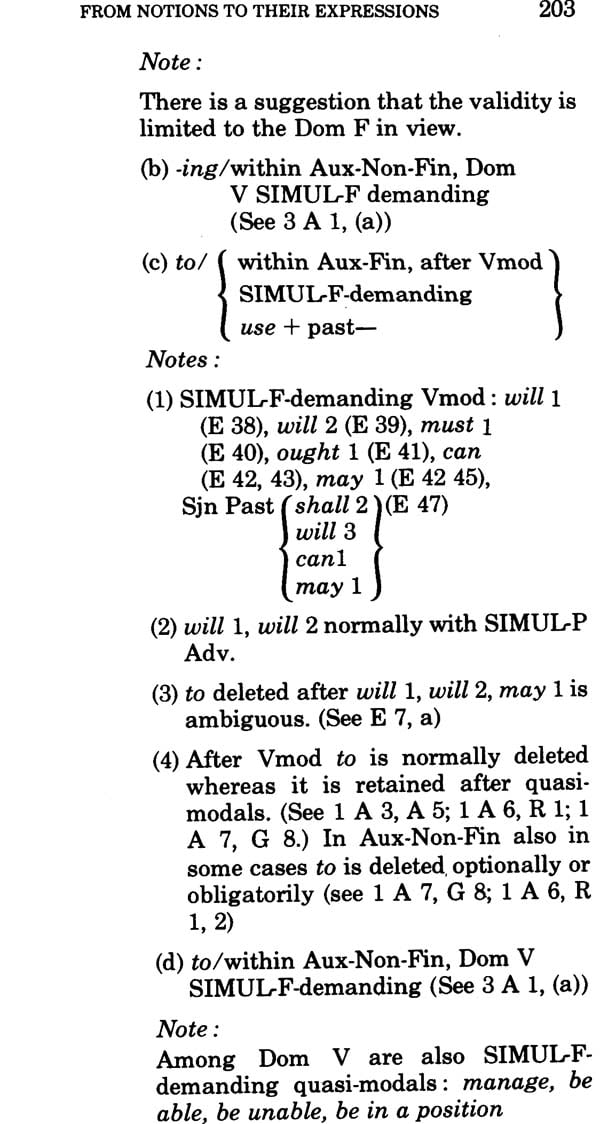

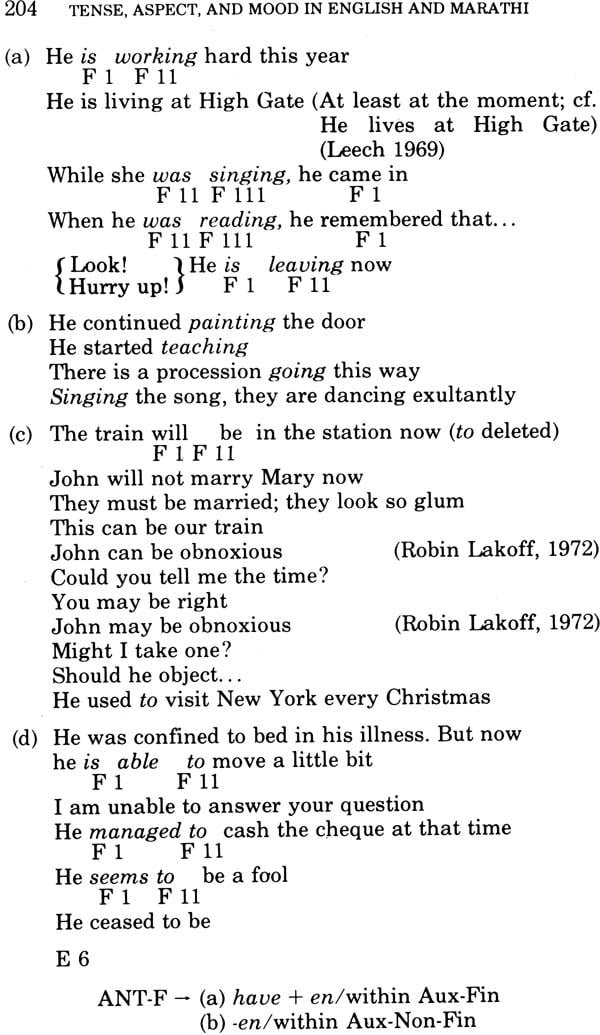

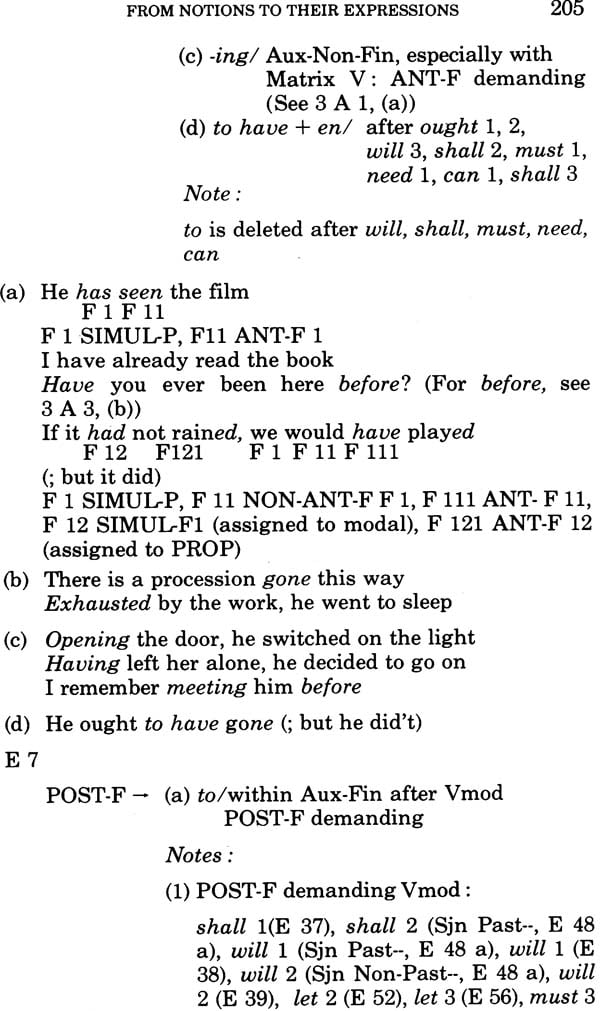

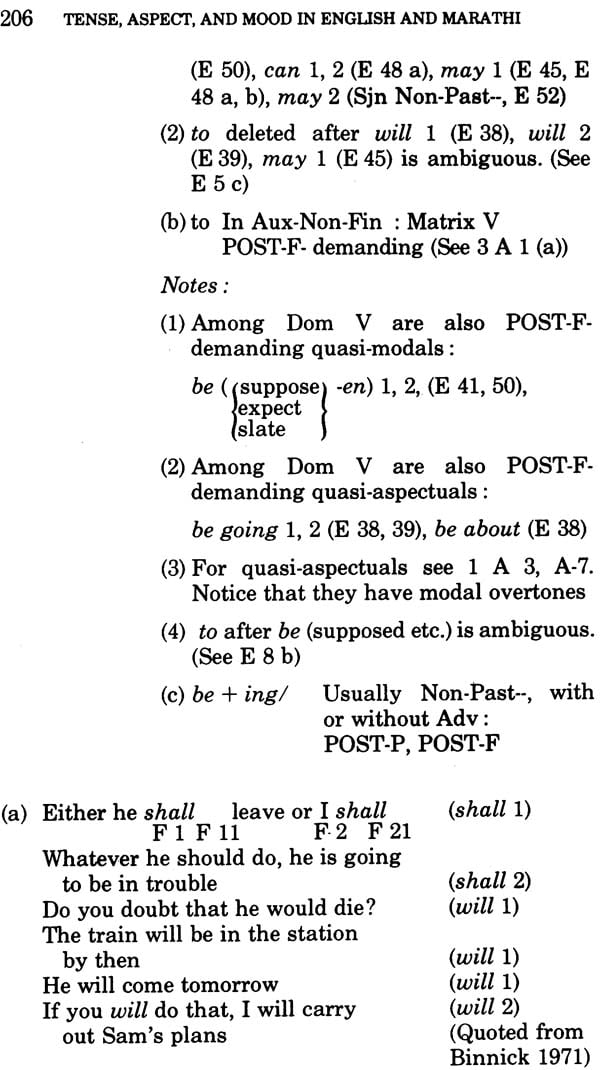

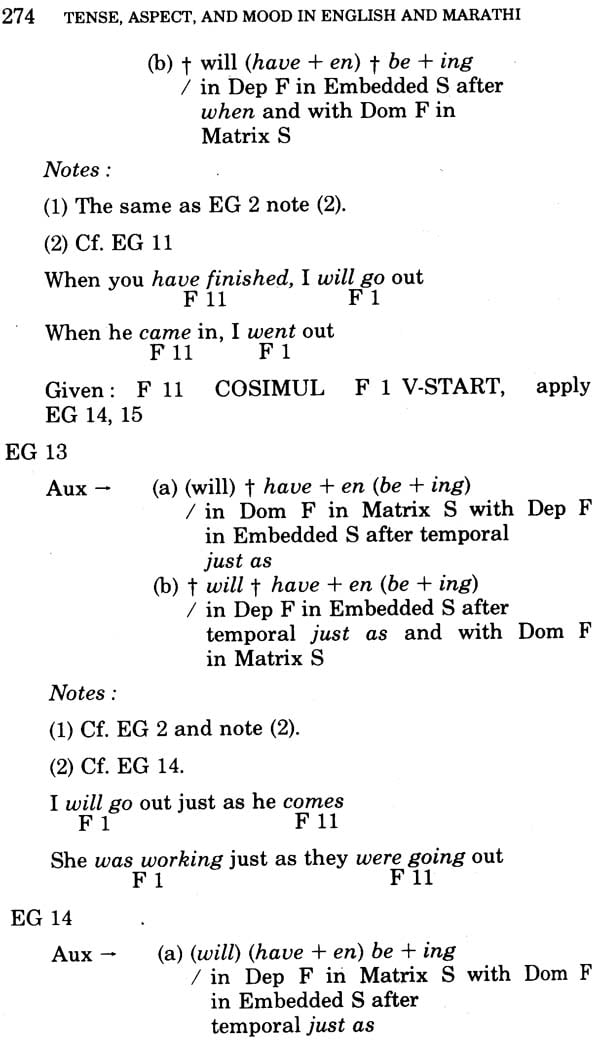

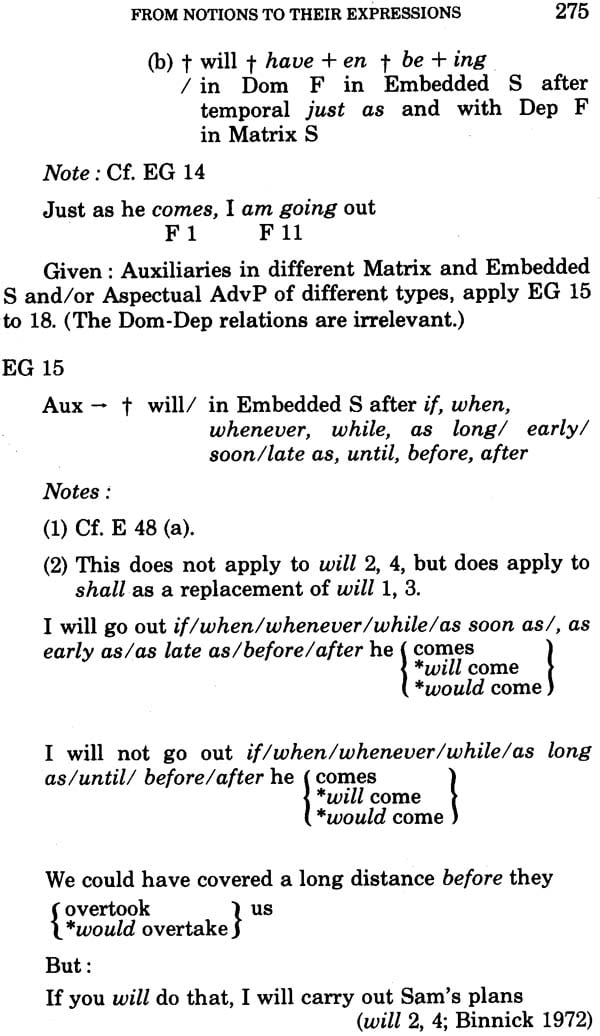

| 4 | From Notions to Their Expressions | 194-340 |

| 4 A | English | 195-278 |

| 4 B | Marathi | 279-328 |

| 4 C | Discussion | 328-340 |

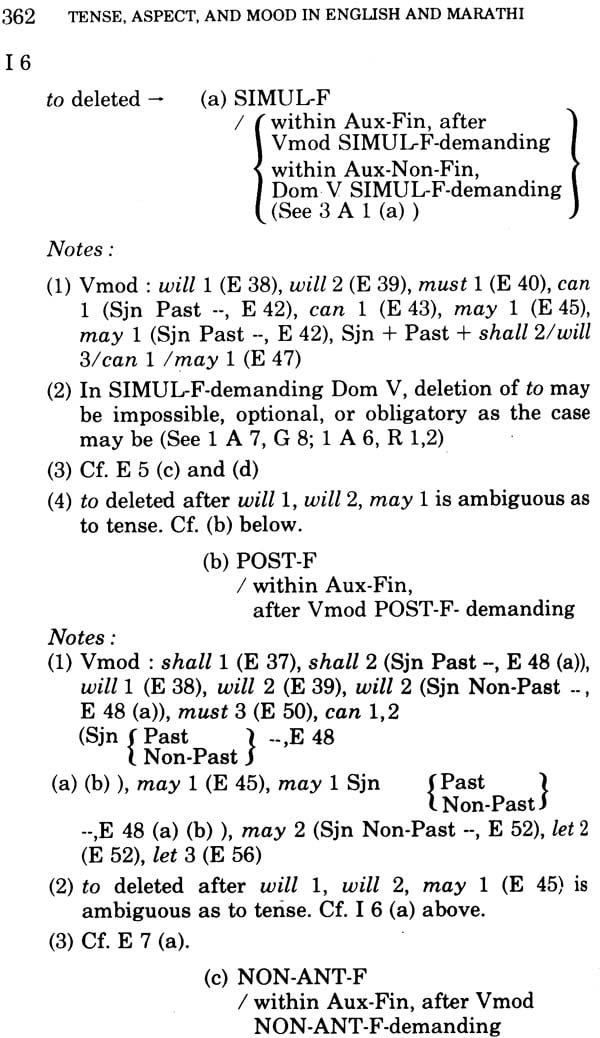

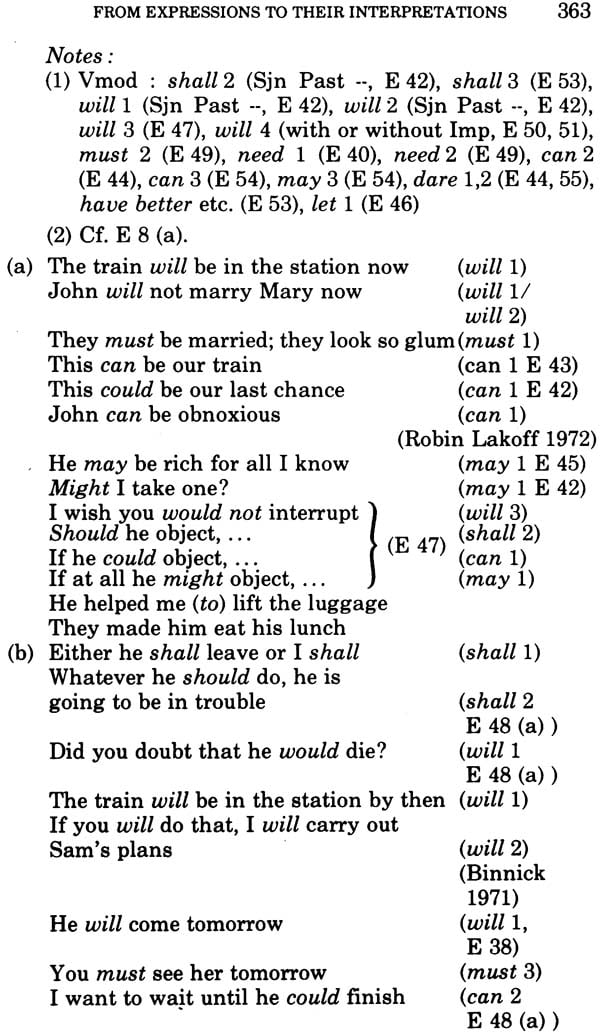

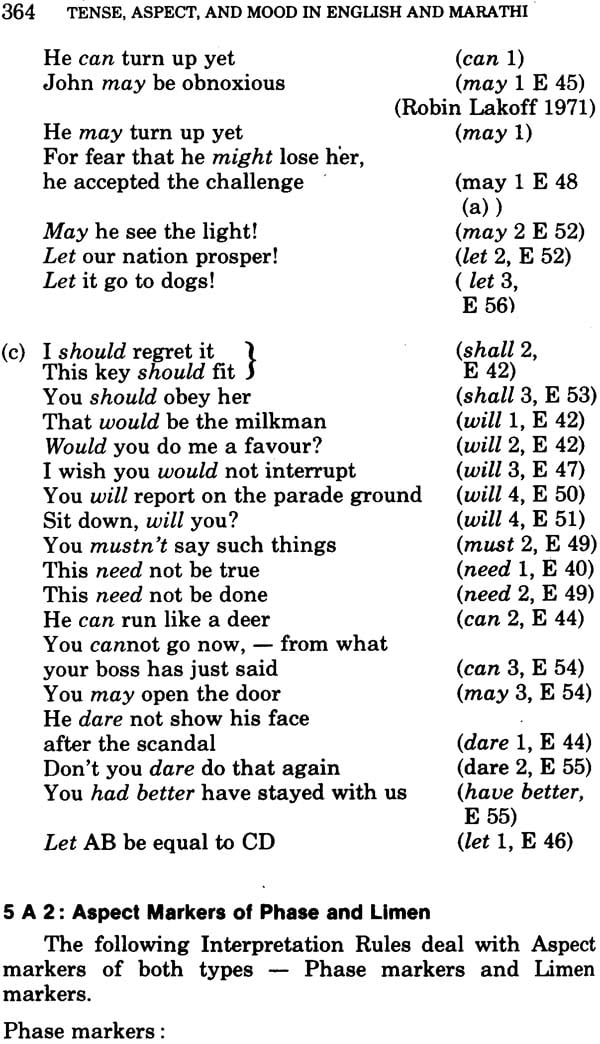

| 5 | From Expressions to Thire Interpretations | 341-467 |

| 5 A | English | 343-403 |

| 5 B | Marathi | 403-451 |

| 5 C | Discussion | 452-467 |

| 6 | Extension and Appllcations | 468-471 |

| Bibligraphy | 472-480 |