The Castaway of Indian Society (History of Prostitution in India Since Vedic Times, Based on Sanskrit, Pali, Prakrit and Bengali Sources) - A Rare Book

Book Specification

| Item Code: | NAH101 |

| Author: | Dr. S.C. Banerji and R. Banerji |

| Publisher: | Punthi Pustak |

| Language: | English |

| Edition: | 1989 |

| ISBN: | 818509425X |

| Pages: | 278 |

| Cover: | Hardcover |

| Other Details | 8.5 inch x 5.5 inch |

| Weight | 350 gm |

Book Description

About the Book

The book 'Castway of Indian Society' Contains Sexual desire; Necessity of prostitution, its effect; Antiquity and evolution of Sexual enjoyment ; Free sex-relation between man and woman ; Prostitutes in the Purana; Prostitution in Tantra; Prostitution in classical Sanskrit and Pali literature; Regional accounts of prostitution; Actor; actress position in society; Sex life in Painting sculpture and architecture; Present day habitat of prostitutes; cause of prostitution; social and religious condition pre-vedic and vedic; Puranic age; age of the great epics; Political History; Prostitution of Arthasastra; society in smirti literature; puranic age; age of the prose and poetical works and dramatic literature women in tantra; Buddhist and Jain literature; Foreigners accounts and epigragranhical evidence; Society in Gupta age; Society in the Deccan; Turko afgan regime; Mughal Period Prostitution in post Mugal India; Source of information about prostitutes; Training of prostitutes; Wiles, Craftes, Nature, Dress and Decoration of prostitutes Devadasi and Visvakarma; Prostitution in Bengal; Prostitution in India Today Indian Call-Girls; Prostitution Abroad; Sale of Humans in the Modern world; A Tale of Five cities; etc.etc.

Prostitution is, perhaps, the oldest profession in the world, an antiquarian and historical interest prompted the author to study the evolution of this profession in india since vedic times. In this book, we have analysed the causes leading to prostitution. The object of this analysis is not merelythe recounting of the reason. From this the social workers and institution like the Ramkrishna Mission, who sincerely believe in the identity of siva and j'va and want to put into practice the ideal that to be kind to beings is to serve God may be aware of the malaise bedeviling the society; the awareness will enable them to eradicate this social evil Rather than curbing it, they can take steps for its prevention. We have dealt with various aspects of prostitution beginning with its origin before doing this, we have down a picture of the Historical setting against which this institution originated and ramified.

We have devoted a chapter to the fading of faded institution of Devadasis or temple-girls tracing its history from its beginning to the present day etc. etc.

About the Author

The author, a retired senior Professor of Sanskrit under Govt. of West Bengal, has been engaged in Indological research for nerely half a century, besides contributing numerous papers to Indological journals, he has published two scores of original works relating to different aspects of Indology. His Literary work includes critical editions, translations and studies. His probe into the Folk-life of ancient and medieval India is the first eversystemetic and sustained attempt in this direction, this published works, interalia, are Tantrain Benga a Brief History of Tantra; Dharma sutras, a study etc;

A Companion to Sanskrit Literature; Flora and Fauna in Sanskrit Literature; Indian society in the Mahabharata ; Kalidasa-Kosa ; Sadukti-Karnamrta; Vibraman Kadevacarita (eng tr.) etc. Crime and sex in ancient India, Historical Gleanings from Sanskrit Literature A Brief History of Tantra Literature; Natya-Sangita-Kosa etc.etc.

Preface

In the Micchakatika of Sudraka, Sakara says that a courtesan excites the passion even of thieves; she is a figurante, destroyer of families, an untameable shrew and a casket of lust. This was, indeed, the general attitude of ancient Indian society towards prostitutes, It is still so, The question that may arise in the mind of the reader-why has such an odious subject been chosen by the author?

Prostitution is, perhaps, the oldest profession in the world, I An antiquarian and historical interest prompted the author to study the evolution of this profession in India since Vedic times.

Despite the age-old opprobrium attached to prostitution, it 'is recognised by many thinkers of to-day as a safety-valve for 'the preservation of morality in society, Without it, the society -would have sunk into abysmal immorality with a section of the population hungering for sexual gratification, but having no means for this, Thus, it is a necessary evil, So, there may be curiosity about how Indian society viewed-it through ages, The satisfaction of this curiosity was another motive for the shaping of this work.

The Kashmirian polymath, Ksemendra (11th cent, in his ; Kalavilasa, says that one, who has insight into the guiles and tricks of evil women, does not fall into their trap. ' An object of writing this book is to lay bare the various gimmicks resorted to by public women so that people, prone to sexual indulgence, may be wary of their wiles; to be fore-warned is to be forearmed.

There are some works on this subject. Some of them are confined to particular, regions like Bombay and Calcutta, Others, dealing with prostitution in, India as a whole have utilisedthe Sanskrit literature only and that too partially; It is our aim, in this work, to dive into a larger number of Sanskrit works, both scriptural and literary, since Vedic times, referring to or dealing exclusively with prostitution. We have tried also to tap the sources in Pali, Prakrit and Bengali literatures. Inscriptions, foreigners' observations and newspaper reports. have also been taken into account.

In this book, we have analysed the causes leading to prostitution. The object of this analysis is not merely the recounting of the reasons. From this the social workers and institutions liks the Ramkrishna Mission, who sincerely believe in the identity of Siva and jva, and want to put into practice the ideal that to be kind to beings is to serve God, may be aware' of the malaise bedevilling the society. This awareness will enable them to eradicate this social evil. Rather than curbing it, they can take steps for its prevention.

We have dealt with various aspects of prostitution beginning with its origin. Before doing this, we have drawn a picture of the historical setting against which this institution originated and ramified.

We have devoted a chapter to the fading or faded institution or Devadasisor temple-girls tracing its history from its beginning to the present day.

A chapter has been written exclusively on prostitution in Bengal (West Bengal and Bangladesh). This is not the result of the author's bias to his own state, but because there are specific references, in Sanskrit and Bengali works, to the courtesans of Bengal, and because Bengal is the only province with the social condition of which the author is most familiar.

In dealing with Indian prostitutes and Devadasis, we have occasionally referred to these institutions in other countries of the east, and some countries of the west.

In one appendix, we have laid down the main laws, enacted in India and abroad, in order to check immoral traffic; in women.

A separate appendix is about the call-girls in India. A study of this chapter will warn the office-going girls, who care for moral purity, against the danger of falling preys to the passionate bosses or the subtle seduction by crafty colleagues.

In one appendix, we have given an idea of prostitution in. the sin cities of the world.

A glossary of terms relating to sex-life has been added. Information about prostitution, as it prevails in India to-day, has been culled from newspapers. There are reports. about some State government officials taking initiative in the marriage of girls who are in the above profession. From this, other States may take the cue, and try to rehabilitate young prostitutes in healthy social life. We feel inclined to echo the sentiments of Engels according to whom the future shape of healthy sexual love will be determined by the wise men of to-morrow who never enjoyed women either in exchange of money or taking advantage of their mastery over them, and by those women who did not, or were not forced to surrender themselves to men except through sheer love.

In preparing such a book, one has to look up to earlier works. Their mention in footnotes and bibliography is the expression of our gratitude to the earlier writers.

The author is indebted to his wife, Sm. Ramala Devi, M.A.". for her ungrudging help in gathering materials and for shouldering the responsibilities of domestic chores so as to provide the author with ample time and opportunity to devote himself to literary work. The fact that her name figures as co-author is evidence of the author's deep gratitude to her.

Thanks are due also to the author's two daughters, Chanda. Chakrabortiand Sarmila Chattopadhyay, his son-in-law, Tushar Kanti Chattopadhyay, who helped him in various. ways the chief of which was the procurement of books. The author's other son-in-law, Dr. (medical) Dipak Chakrabarty, kept him fit; without physical fitness nothing is possible. The author is obliged to Sri Sibdas Chaudhuri, the learned ex-Librarian of the Asiatic Society, Calcutta, for drawing his attention to some books. The kind of courtesy, shown by Sri Jagadish Saha, formerly Asstt, Librarian of National Library, Calcutta, and Sri Achintya Mallick, Junior Technical Assistant of the same library, is extremely rare now-a-days.

The author will be grateful if the kind readers point out lapses of omission and commission in the book, and give suggestions for its improvement.

Introduction

General Remarks

Prostitution usually means the surrender of a woman's body for the sexual enjoyment by a man in exchange of money. In the society there are some women who indulge in clandestine union with men, sometimes out of lust and sometimes for a. mess of pottage. Such women are adulterous. Adultery is a penal offence in all civilised countries. Adultery and prostitution are not synonymous. A woman, married or unmarried, may be a prostitute. Adultery means voluntary sexual intercourse of a married person with one of the opposite sex, either married or not. The Ten Commandments of the Bible and the Panchshil (Five rules of conduct) prohibit adultery (or, for that matter unconventional sexual enjoyment) in clear terms.

In ancient India, we find women as the eternal temptress as well as a replica of goddess. In fact, the twofold aspect of women's character is found in all times and all climes. Even now, when civilisation and culture have, it is claimed, reached the apogee of perfection, there are women who are ostensibly chaste, but, in reality, secret prostitutes. Such a woman is called demi-monde. The Gudhajiva, mentioned in ancient Indian works, apparently used to live a normal life, but resorted to clandestine sexual life.

Words denoting prostitute

Prostitutes have been variously called in Sanskrit literature. Each of the different words, denoting a strumpet, has a significance of its own. The words, commonly denoting such a woman, are as follows;

Vesya(rarely vesya)-A woman tempting men by her Vesaor dress.

Sadharani-Common or enjoyable by all (public woman).

Pumscali-A woman running after a man.

Vandhaki-A woman having sexual tie with many men.

Rupajiva-A woman earning bread by physical charm.

Ganika-Enjoyed by gana, i.e. many or one who lives in a group.

Varangana(also varastri, varayosit, varavanita, varavadhu or varanari)-A woman enjoyed by men by turn.

Kuttanior Sambhali-A prostitute procuring men.

Panyastrior Panyayosit-A woman used as a commercial commodity.

Kumbhika-Perhaps the same as Kumbhadasidenoting Kuttani.

Rupadasi-Enslaved for physical beauty.

Patakavesya-Such a prostitute is stated to be a forest-dweller.

In connection with prostitution in Paliliterature, the Pali words, denoting prostitute, have been stated.

In different dictionaries, the following words are found to denote prostitute ;

Ksudra, Salabhanjika (Jatadhara), Jharjhara, Suta, vara-vani, Bhandahasini, (Sabdaratnavali), Lanchika, Bandhura, Kamarekha, Barbti (Sabdamala), Bhujisya (Hemacandra), Bhogya, Smaravithika ( Rajanirghanta ), etc.

Ksirasvamin(C. 8th cent., according to some; l1th, according to others), in his commentary on the Amarkosa(C. 4th cent.), gives derivative meanings of some words denoting prostitute.

According to the Kamasutra(i/3/24), a Ganika, as distintinguished from Vesya(common harlot) is a courtesan who is highly accomplished and experienced in sixty-four arts; e.g. Vasantasenli. of the drama, Mrcchakatika. The above two words appear to have been used synonymously; e.g. Yajanavalkyasmrti(i/141, 161). The Ganikas were held in esteem even by kings, and praised by the appreciative people; such a woman or her company was coveted.

It is not clear whether the Ganikadasiof the Arthasastra(ii/27) was herself a courtesan or an attendant of a courtesan. In this work, the words pratiganika, dasi, silpakarika and kausika-stri. also denote prostitute.

It seems the words Adasi, Avaruddha, Krtavarodha, Duhitrka and Kumarietc. also were used in this sense.

The daughter of a ganikausually became a ganikaor svayambhava(voluntarily deserting the family of the husband or father).

Sexual desire, a pristine instinct

Sexual desire is one of the pristine instincts of beings. In English, it is called the original sin. Man makes God in his own image. So, gods are represented as passionate.

Necessity of prostitution, its effect

It is a primitive, perhaps the oldest profession. There is difference of opinion as to whether or not it should be allowed by the State. It is argued by some that the institution, which may lead people, particularly the young, astray, is, as such, harmful; it should be eradicated. Others consider it a safety valve offering an opportunity to those who hanker after sexual union, but cannot fulfill their desire due to poverty or some other reasons. In some cases, repression of the natural sexual urge leads to psychological complications sometimes culminating in insanity.

This profession, ignoble though it may seem, provides livelihood and shelter to those women who are deserted by husbands or fall victims to the indifference or neglect of their guardians.

Prostitution may lead to some social evils. Well-to-do donothing young people may be entrapped by prostitutes. Enjoyment of public women may cause venereal diseases, then making people despicable in society or rendering them unfit for work for the rest of life.

Antiquity and evolution of sexual enjoyment

Desire for the gratification of sexual desire is coeval with creation. In India, the earliest evidence is, perhaps, furnished by relics of Indus Valley Civilisation approximately dating back to the third millenary B.C. A bronze replica of a nude dancing girl is supposed by some to represent a prostitute. It has a necklace, and its arms are almost wholly covered with bangles; the hair-do is complex. Its standing posture is exciting. One of the hands is on the hip and the other on a thin long shank which is half curved. An animated attitude marks the figure. According to some, it is an Indian version of a temple-girl of contemporary Middle Eastern region.

The Rgveda(C. 1500 B.C.) contains references to sexual union of man and woman. Even the gods are stated to be subject to this urge. Even incest was, perhaps, in vogue. We find (Regveda X.10) goddess Yami imploring her brother, Yama, to satisfy her carnal desire. Yama, however, refused. Illegitimate sexual relation in the Vedic society is vouched by the words jara(Rv. i/66/4, i/69/l, vi/55/45, vii/10/10, ix/38/4) and jarini(x/34/5) denoting paramour and concubine respectively. The vogue of prostitution is attested by the words sadharani(i/167/4) and vesyii(vi/6l/14, vii/18/l7). The 'vesya' was, perhaps, derived from vesya(i/126/5). Winternitz thinks (History of Indian Literature, I, p. 67, 1927) that, in this age, many brotherless women, unprotected and companionless, took to prostitution. This appears to be confirmed by the Rgveda(iv/5/5) and Atharvaveda(i/17/1).

The hypothesis of Pischel and Geldner (Vedische Studien, I, p. xxv) that, as in Vaisali of the Buddha's time (5th c. B.C.) or in the Athens of Pericles (C. 490-429 B.C.), there was organised prostitution in Vedic India, is not based on sufficient.

From some passages in the Rgveda it appears that women freely mixed with men in feasts, dance, etc. This, however, does not warrant the assumption that those women were prostitutes.

The SuklaYajurveda(xxx/5-6, 22) mentions pumscaliand kumariputra (son of a virgin). Pumscalioccurs also in the Atharvaveda (xv/2/1). This Veda mentions ganikain connection.Vratyanusthana. Mahanagni Atharva, xiv/1/36 and AitareyaBrahmana (i/27/1) is taken by some to refer to prostitute. The VajasaneyiSamhita of the Yajurveda(xxx/15) contains the words Atitvariand Vijarjarawhich appear to indicate the vogue to prostitution.

The Vedic women used to participate in various folk festivals. According to scholars like Pischel, courtesans also took part. Sabhavati Yosa (Rv. i/167/3), according to some, denotes a woman participating in assemblies. Some think that the dancing goddess Usa. (Dawn), dressed in Adhipesa(embroidered garment) and baring her bosom (Rv. i/92/4, x/95/9), is a deified form of courtesan.

The Vedic rite, Varuna praghasa, hints at the existence of free love and clandestine lovers. In it, the sacrificer's wife was asked about her secret lover. Reciprocal abuse of a Brahmin student and a courtesan formed part of the rite called Mahavrata.

The Chandogya Upanisad (iv/4) contains the legend of Satyakama who is stated to have been born to Javala who had no husband.

In the historical period, the Arthasastra appears to testify to the fact that, long before the Maurya period, the courtesan were looked upon as a useful section of the society.

Contents

|

| Preface | vii |

|

| Chronology | Xi |

| I | Introduction | 1-28 |

| II | Historical Background | 29-41 |

| III | Position of women in the social and religious milieu | 42-83 |

| IV | Sources of information about prostitutes | 84-107 |

| V | Training of Prostitutes | 108-117 |

| VI | Wiles, crafts, nature, dress and decoration of prostitutes | 118-129 |

| VII | DevadasiAnd Visakanya | 130-149 |

| VIII | Prostitution in Bengal | 150-180 |

| IX | Epilogue | 181-186 |

|

| Appendices |

|

| I | Indian and International Laws and Conventions relating to prostitution and traffic in Women | 187-190 |

| II | Prostitution in India to-day | 191-204 |

| III | Indian Call-girls | 205-210 |

| IV | Prostitution Abroad | 211-216 |

| V | Sale of humans in the modern world | 217-218 |

| VI | A Tale of five cities | 219-225 |

|

| Glossary | 226-231 |

|

| Bibliography | 232-240 |

|

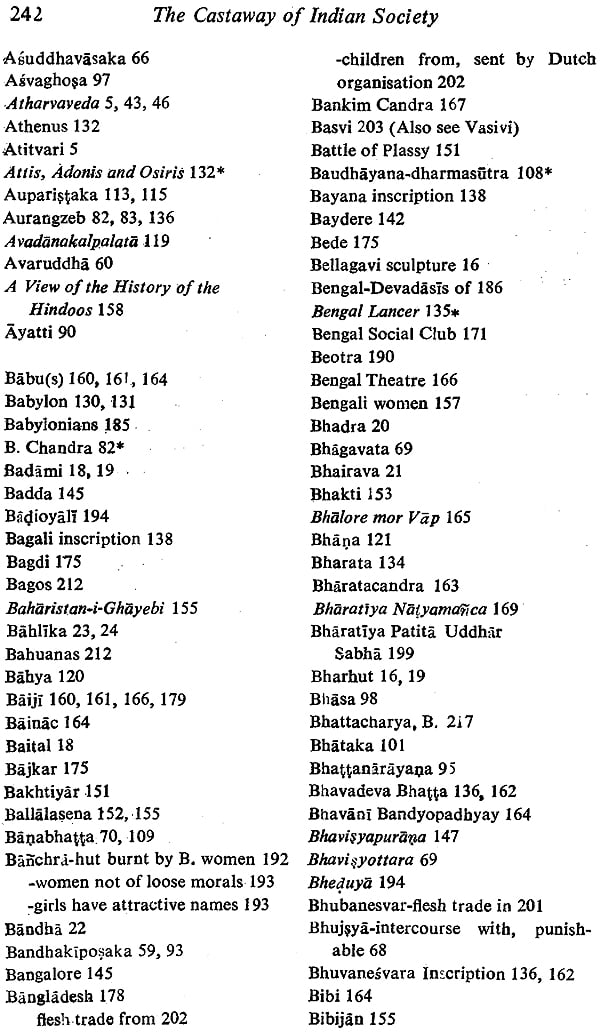

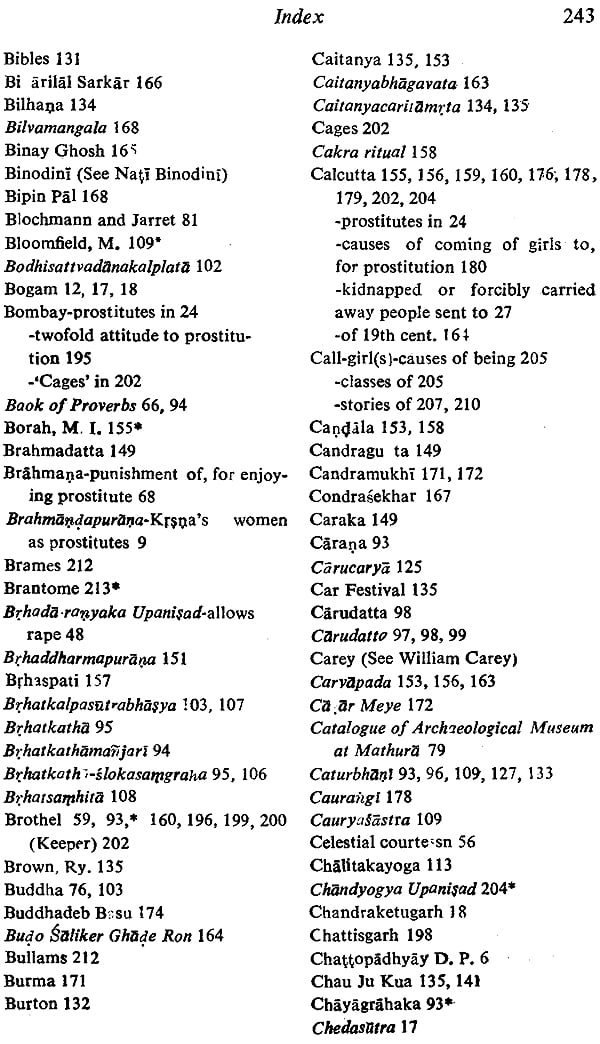

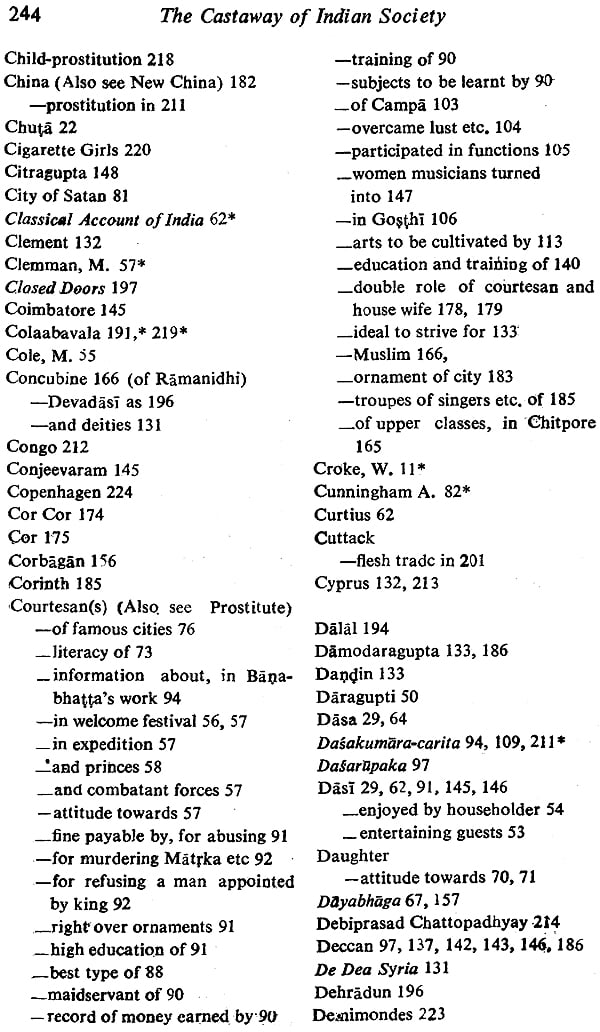

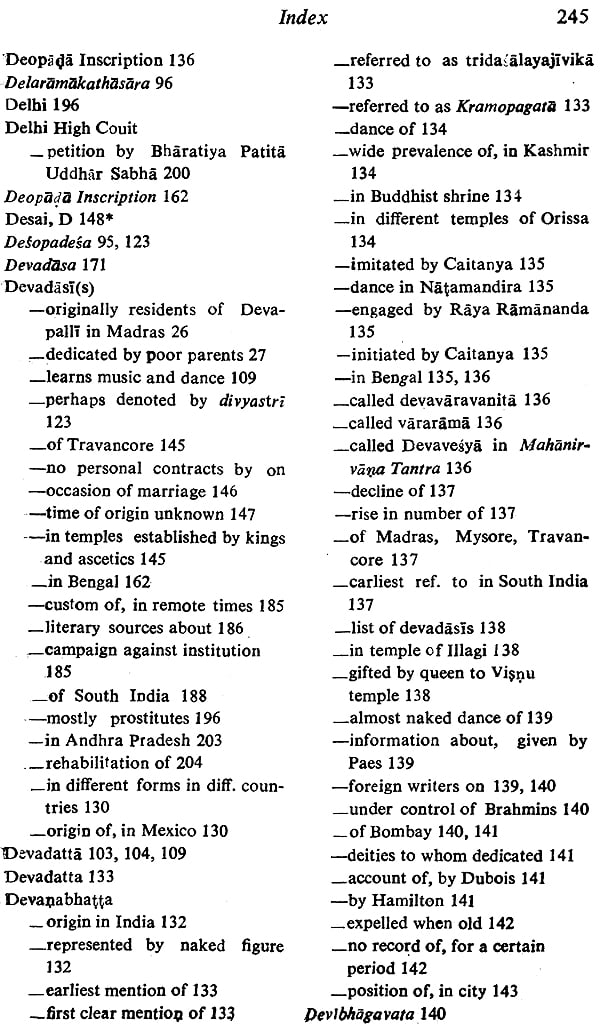

| Index | 241-260 |