Outline of Abhinavagupta's Aesthetics (An Old and Rare Book)

Book Specification

| Item Code: | NAM680 |

| Author: | V. M. Kulkarni |

| Publisher: | Saraswati Pustak Bhandar, Ahmedabad |

| Language: | English |

| Edition: | 1998 |

| Pages: | 118 |

| Cover: | Hardcover |

| Other Details | 9.5 inch X 7.0 inch |

| Weight | 360 gm |

Book Description

The theory of rasa is Abhinavagupta's major contribution to Aesthetics. His conception of rasa relates to poetry and drama. It can be equally applicable to other forms of art as well.

This monograph deals with the various aspects rasa is laukika or alaukika; whether all rasas are pleasurable or some pleasurable and others painful; where is rasa located – is it in the poet in the character or in the actor or in the spectator; whether the sattvikabhavas are only physical or mental or are they both; whether rasas are connected with the four purusrthas:

An earnest attempt is made here to provide satisfactory answers to these questions. Mahimabhatta's views on Abhinavaguptta's rasa theory are also discussed.

Dr. V. M. Kulkarni, formerly, Professor of Sasnskrit and Prakrit (Maharashtra Educational Service, Class I), Director of Languages, Maharashtra State, Mumbai, Director, B. L. Institute of UIndology (Patan, Now shifted to Delhi) has taught Sanskrit and Prakrit Literature, Sanskrit Poetics and Aesthetics to post-graduate students of various universities for several years. As an Author or Editor he has to his credit several publications.

In the two splendid commentaries, Locana on Dhavanyaloka and Abhinavabharti on Natyasastra, Abhinavagupta sets forth his theory of rasa. It rightly regarded as his major contribution not only to Sanskrit literary criticism but also to Sanskrit Aesthetics as a whole. M. Hiriyanna observes in his Foreword to Dr. V. Raghavan's book The Number of Rasas: "The conception of rasa though it is here dealt with chiefly in its relation to poetry, is general and furnishes the criterion by which the worth of all forms of fine art may be judged." Elsewhere too he says: "Though the theory applies equally to all the fine arts, it has been particularly well-developed in relation to poetry and drama."

In the chapter called Rasadhyaya (Natyasastra, Ch. VI) Bharata declares: 'na hi rasadrte kascid arthah pravartate' – meaning "every activity (on the stage) is aimed at the creation or generation of rasa". Immediately after this statement he sets forth his famous rasa-sutra: Vibhavanubhava-vyabhicari-samyogad rasa-nipattih, that is, "out of the union or combination of the vibhavas (determinants), the anubhavas (consequents) and the vyabhicaribhavas (transitory feelings) rasa arises or is generated".

Now, the ancient writers on dramaturgy, whom Bharata also follows, invented an entirely new terminology to impress on our minds the basic distinction between real life and life in the creative imagination-in the realm of literature-the real world and the world of drama, The vibhavas, anubhavas and vyabhicaribhavas belong only to art and not to real life. They, however, correspond to the karanas, the karyas and the sahakarikaranas. The rasas correspond to the sthayibhavas (the dominant or permanent emotions.) The vibhavasis are therefore called alaukika (nonworldly, or transcendental.)

The four exponents of the rasasutra, Bhatta Lollata, Srisankuka, Bhattanayaka and Abhinavagupta differ amongst themselves in their interpretation of the two words, samyoga and nispatti. They take the word nispatti to mean utpatti (production, generation), anumiti (inference), bhukti (aesthetic enjoyment) and vyokti (manifestation, suggestion) respectively. They understand by the word samyoga, it would seem, utpadya-utpadaka-bhava, jnapya-jnapaka-bhava, bhojya-bhojaka-bhava and vyangya-vyanjakabhava between vibhaadis and rasa respectively. That is to say, (i) The rasa is what is produced and the vibhavadis are the causes that produce rasa; (ii) the rasa is what is inferred and the vibhavadis are the characteristic marks or signs; (iii) the rasa is what is to enjoyed (aesthetically); and finally (iv) the rasa is what is suggested and the vibhavadis are the factors which suggest the suggested meaning.

Abhinavagupta presents the views of Lollata Sankuka and Bhattanayaka; each view if followed by its criticism. Finally, he sets forth his own view in great detail. In spite of the criticism of the earlier writers views Abhinavagupta acknowledges his debt to them before introducing his own position. He informs us that he has built his own theories on the foundations laid by them; and that he has not (completely) refuted their views but only refined them:

Tasmat satam atra na dusitani matani tanyeva tu sodhitani.

Again, in the course of the exposition of his own siddhanta he accepts the views of Lollata, Sankuka and Vijnanavadinas in a modified form: esaiva copacayavasthastu desadyaniyantranat: anukaro'pyastu bhavanugamitaya karanat; visayasamagryapi bhavatu vijnanavadavalambanat.

("We may say equally well that it consists of s state of intensification-Lollata's doctrine-using this to indicate that it is not limited by space, etc; that it is a respoduction-using this word to mean that it is a production which repeats the feelings – its., "to mean that it is an operation temporally following the feeling." – This is the view of Sanskrit; and that it is a combination of different elements – this conception being interpreted in the light of the doctrine of the Vijnanavadin.)

An view of these statements made by Abhinavagupta it was thought unnecessary to deal with the views of earlier writers at length in this treatise but briefly refer to them and concentrate on Abhinavagupta's position in regard to rasa-nispatti (production or generation of rasa) and rasasvada (aesthetic enjoyment of rasa), the nature of rasa and other related matters.

Abhinavagupta in the two commentaries has discussed a series of questions relating to beauty and rasa: What is the nature of beauty? Whether it is subjective or objective or subjective-cum-objective. Whether the permanent emotion itself is rasa-sthayyeva rasah – or rasa is altogether different from the permanent emotion – Sthayivilaksano rasah. Whether rasa is sukha-duhkhatmaka, i.e, some rasas are sukhatmaka (pleasurable) and some other duhkhatmaka (painful). Or whether all the rasas are anandarupa (characterised by bliss, perfect happiness). Whether rasa is laukika (wordly) or alaukika (nonwordly, transcendental). The there is the question of sattvikabhavas (asru=tears, sveda=perspiration, etc., involuntary states). Whether they are physical manifestations (jada and acetana in nature) or sentient (cetana) in their nature & internal? In other words, whether the sattvikabhavas are like bhavas (rati-love, hasa-laughter, etc,; and nirveda – world weariness, glani-physical weakness, etc.) or like anubhavas – the external manifestations of feeling (mental state) such as sidelong glances, a smile, etc., or whether they are of dual nature? Another important question regarding rasa as discussed by Abhinavagupta, is about the asraya (location or seat) of rasa. Could it be poet himself or the character (say, Rama, Dusyanta, etc.) or the actor who plays the role of Rama, Dusyanta, etc., or the spectator himself? Further, whether the rasa are meant to provide sheer pleasure (pri ti) to the spectators or are also meant to give (moral) instruction in the four ends of human life (purusartha)?

Naiyayikas like Mahumabhatta vigorously oppose Anandavardhana's newly invented sabdvrtti (power or function of word) called vyanjana which is readily accepted and defended by Abhinavagupta, and assert that the purpose for which vyanjana is invented is best served by the process of inference (anumiti, anumana). With the sole intention of enabling readers to judge for themselves how far the criticism of Mahimabhatta directed against Abhinavagupta is fair and just, the views of Mahimabhatta on how rasas arise and they are enjoyed by sahrdayas are presented at the end of Abhinavagupta's exposition.

Here I take the opportunity of gratefully acknowledging my indebtedness to A. B. Keith, M. Hiriyanna, V. Raghavan, J. L. Masson and M. V. Patwardhan. I am especially grateful to J. L. Masson and M. V. Patwardhan on whose two works, one on Santarasa and the other on Aesthetic Rapture, I have freely drawn.

Now it is my pleasant duty to thank those who have helped me in bringing out this monograph. I am grateful to Dr. G. S. Bedagkar, formerly professor of English, Elphinstone College, Mumbai and Principal, Vidarbha Mahavidyalaya, Amaravati for going through this monograph and making useful suggestion. I am also very happy to record my sincere thanks to my dear friend, Prof. Sureshbhai J. Dave for all his kind help seeing this publication through. I have also great pleasure in thanking Smt. Mrudula Joshi for editorial assistance. I sincerely thank my friend, Shri Ashwinbhai Shah, Proprietor,, his colleague Shri Hirabhai Vora, Saraswati Pustak Bhandar for readily agreeing to publish this monograph in Saraswati Oriental Series. I also thank the Printers, Dhrumil Graphics for the beautiful printing and attractive get up.

In the West the theory of beauty or aesthetics or the inquiry into the charater of beauty in Nature as well as in art, has come to be recognised there as a regular part of philosophy. Western philosophers study the problem of the beautiful in relation to the good and true. Controversies have prevailed regarding the questions: what are the characteristics of beauty? Whether it is objective or subjective, whether the artist (including the poet) as creating beauty must preach morality? or whether his province is different from a preacher of morality? Various theories of beauty have been propounded by Plato, Aristotle, Kant, Coleridge, Schopenhauer, Hegel, Croce and others. Their philosophical discussion of these questions makes aesthetics like ethics an important branch of philosophy.

In India, however, the study of aesthetics does not form a branch of philosophy. It was carried on by a distinct class of thinkers, literary critics, who were not, generally speaking, professional philosophers. Naturally, they nowhere systematically discuss in their works the essential characteristics of art in general and of the fine arts in particular. They deal mainly with beauty in creative literature, one of the fine arts. Further, they do not explicitly or emphatically speak of the distinction between the Fine Arts and the "Lesser" or "Mechanical" Arts - the Fine Arts comprising Architecture, Sculpture, Painting, Music, Poetry (including the Drama) and Dancing, and the "Lesser" or "Mechaincal" or "Useful" Arts of the smith, the carpenter, the potter, the weaver, and others like them. According to the Western crictics, "The distinction which separates these two classes is based upon the fact, that broadly speaking the arts of the first class minister to the enjoyment of man, while those in the latter minister to his needs. They are both alike manifestations of the development of man; but the Fine Arts are concerned mainly with his moral and intellectual growth, and the Lesser Arts with his physical and material well-being. "Nor do they speak of the two classifications of the Arts. "The first (classification) divides them into the Arts of the "Eye" and the Arts of the "Ear", according as they respectively use one or other of the senses of sight or hearing as their primary channel of approach to the mind. Thus grouped we get the arts of Architecture, Sculpture and Painting placed in broad contrast to the Arts of Music and Poetry. By the second (classification) they are arranged with reference to the greater or lesser degree in which they severally depend upon a material basis for the realisation of their respective purpose. "Nor do they venture upon a definition of Art, applicable to all the (Fine) Arts. They merely attempt a definition of one of the Fine Arts, namely, poetry (or Creative literature as such) and investigate into the source of literary beauty. Finally, they arrive at the conception of rasa as the first and foremost source of Beauty in Literature. Modem scholars like M. Hiriyanna say" ... the numerous works in Sanskrit on poetics which, though their set purpose is only to elucidate the principles exemplified in poetry and the drama, yet furnish adequate data for constructing a theory of fine art in general." And, "The conception of rasa. is general and furnishes the criterion by which the worth of all forms of fine art may be judged." There is the other view too, expressed by some scholars in their modem writings that in the context of other fine arts the term rasa is used by metaphorical extension only and the rasa theory is not applicable to other fine arts. There is much that could be said in favour of and against these two conflicting views. But without entering into this controversy let us revert to aesthetics investigation carried on by the Sanskrit alamkarikas in relation to the fine art of poetry (including the drama), which is placed among all the fine arts 'highest in order of dignity.'

In the growth or development of Sanskrit literary criticism we discern two distinct stages : The first stage is represented by the early writers on poetics who preceded Anandavardhana, and the second by Anandavardhana, his able commentator Abhinavagupta, and reputed followers like Mammata, Visvanatha, Jagannatha and others, not so reputed. Bhamaha, Dandin, Ubhata, and Rudrata - these early alamkarika-s are regarded by common consent as the protagonists of the view that in kavya (poetry, creative literature) it is the alamkaras that enjoy the pride of place. They were aware of the Pratiyamana sense but they were not aware of Anandavardhana's theory that pratiyamana sense or dhvani is' the soul - the essence of poetry. They, however, include this pratiyamana sense in their definitions of figures like aprastuta-prasamsa, samasokti; aksepa, paryayokta, etc. deal with other sources of beauty, namely, gunas like madhurya (sweetness), vrttis (dictions) like upanagarikn (the cultured) and the like. They fail to notice the central essence of kavya as their attention is concentrated for all practical purposes on its 'body'- the outward expression or externals of poetry, viz. sabda (word), and artha (sense). Certain forms of these are regarded as dosa-s and certain others as gunas; and they hold that what confers excellence on poetry is the absence of the one and the presence of the other. No doubt, there are minor differences in certain matters among these alamkarikas. For instance, some like Udbhata make no distinction between gunas and alamkaras. Varnana, however, makes a clear distinction between them. Dandin defines and distinguishes between the Vaidarbha and the Gauda styles. Bhamaha holds that there are no such two distinct styles. These and such other minor differences apart, these alamkarika-s reveal cognate ways of thinking. We may, therefore, regard them as, on the whole, respesenting the first stage in the growth of literary criticism and aesthetics.

It is Anandavardhana, the author of Dhvanyaloka, an epoch-making work, who completely revolutionized the sansktrit poetics and aesthetics by his novel theory that dhvani (suggestion) is the soul of poetry-the very essence of creative literature. This novel theory he formulated and clearly expounded for the first time. His statement in the opening karika – "kavyasyatma dhvaniriti budhair yah samamnatapurvah" is not to be taken literally. The makes this statement with a view to investing it with authority. He distinguishes between two kinds of meaning – the vacyartha (including the laksyartha or gaunartha) and the vyangyartha, the expressed or denoted or denoted meaning and indicated meaning on the one has and the suggested meaning on the other and holds that the expressed meaning (as well as the indicated meaning) and the words in which it is clothed, constitute the mere body of kavya. They together are the outward embodiment of the suggested meaning – the outward element of kavya and not its inner soul-emotion. He attempts to estimate or judge the worth of a poem by reference to this central essence rather than to the expressed meaning. The words and the expressed meaning are really speaking, external but these alone appealed to the earlier writers on poetics. They misjudged the true importance of the central essence of poetry and assigned to it a subordinate place. Anandavardhana concentrates concentrated his attention on the suggested meaning which forms the real essence of poetry. Whatever in sound (word) or sense subserves the poetic end in view (rasa, bhava, etc.,) is a guna; whatever does not, is a dosa. Dosa-s and guna-s are relative in character. There is no absolute standard of valuation for them. They are judged only in reference to the inner or suggested meaning which forms the poetic ultimate.

The suggested meaning is three-fold:

1.a bare idea, fact(vastu), 2. a figure (alamkara) and 3. rasa, bhava and the like. If the earlier or older alamkarika-s concentrated on an analysis of the outwards expression of kavya, Anandavardhana occupied himself with what this expression signifies or suggests. The expression is important to him as only a means of pointing to the suggested meaning. Anandavardhana's theory of rasadi-dhavai exactly corresponds to the Upanisadic doctrine of atman. The earlier alamkarika-s mistake the body (sarira) of poetry for its soul (atman)-the externals of true poetry for its essence.

Poetry versus Philosophy:

The alamkarika-s often draw our attention to the dichotomy or distinction between poetry and philosophy. We have the oft-quoted verse from Bhamaha on this distinction:

"Even a stupid man can learn the sastra-philosophy from the teachings of the teacher. But poetry is only given to the person who has imaginative (or creative) genius-pratibha and that only once in a while."

Another well-known verse, probably from Bhatta Tauta's Kiivyakautuka, now lost, clearly distinguishes between sastra and kavya, Philosophy and Poetry:

"There are two paths of the goddess of speech: one is the sastra (Philosophy) and the other is kavikarma (Poetry). The first of these arises from intellectual ability (prajna) and the second from genius (pratibha)"

He (Bhatta Tauta) also refers to the twofold gift of the poet, of seeing visions of striking beauty (darsana) and of communicating to others through appropriate language the visions he sees. Rudrata defines sakti which is synonymous with pratibha as follows:

"Sakti is that whereby in a mind, that is free from distractions, subjects of description always flash and words that are perspicuous shine forth."

Rajasekhara defines pratibha as:

"Pratibha" is that which causes to appear in the mind (of the poet) appropriate words, meanings or ideas, alamkaras, diction and style (uktimarga) and other similar things as well." He divides pratibha into two kinds: creative (karayitri - that with which poets are gifted) and appreciative (bhavayitri-which belongs to sahrdaya-s, sensitive and sympathetic .critics or readers).

Abhinavagupta quotes the following definition of Pratibha:

"(Creative) imagination is that form of intelligence which is able to create new things." He further adds: "the speciality of a great poet's creative imagination consists in the ability to produce poetry that is endowed with beauty and clarity due to the onrush of emotional thrill in the heart." Elsewhere he defines sakti in almost identical terms.

The most famous definition of pratibha occurs in the following passage quoted by Vidyacakravartin, in his Sampradnyaprakasini:

"Smrti is that which refers to an object of the past. Mati refers to something that is still in the future. Buddhi deals with that which is present and prajna belongs to all the three times (past, present and future). Pratibha is that (form of) intelligence which shines with ever fresh delineations of pictures of the matters to be described with 'ullekha' or ever fresh flashs of ideas (with 'unmesa')"

Mahimabhatta describes the nature of pratibha in a striking manner:

"Pratibha is that intellectual function of the poet whose mind is concentrated (or fixed) on thinking about words and meanings that are appropriate to rasa (to be portrayed in the poem). It arises for a moment from the contact of the poet's mind with the essential nature (of his own atman)."

"It is that which makes the things that exist in all the three worlds seem as if they were right before one's very eyes, and hence it is known as the third eye of Siva."

In brief, "Pratibha is that power whereby the poet sees the subjects of his poem as steeped in beauty and gives to his readers in appropriate language a vivid picture of the beauty he has seen. It is a power whereby the poet not only calls up in his reader's heart the impressions of the past experiences, but whereby also he presents ever new, wonderful and. charming combinations and relations of things never before experienced or thought of by the plain or ordinary man. A poet is a seer who sees visions and possesses the additional gift of conveying to others less fortunate through the medium of language the visions he has or the dreams he dreams."

We have dwelt on pratibha for long for the simple reason that it is regarded if not universally, generally, as the sole cause of poetry. Whatever is touched by the magic wand- power of pratibha becomes a-laukika, sui generis, unique; the world of beauty, the poet's creation is altogether different and distinct from our everyday world. What renders the poet's creation unique is his pratibhta In other words, creative literature whose hall-mark is originality is the art of pratibhii (genius). And by extension we might as well say that like Creative Literature, Architecture, Sculpture, Painting, Music and Dancing are also the arts of pratibha.

Pratibha is undoubtedly as already said, the sole cause of poetry but to appreciate this poetry you require a reader who is also gifted with pratibha. Abhinavagupta recognises this affinity of nature between the poet and the reader of poetry when he declares in the mangala sloka at the commencement of Locana:

"Victorious is the essence of speech called kavi-sahrdaya, (the inevitable pair involved in all aesthetic activity) the poet, the artist, and the discerning enjoyer, the critic."

Of the pair, the word sahrdaya cannot be easily rendered in English. It literally means 'one of similar heart' - 'one who is of the same heart', of like heart with the poet. It may be taken to signify a person whose insight into the nature of poetry is, in point of depth, next only to that of the poet. Abhinavagupta thus defines the sahrdayas: "Those people who are capable of identifying with the subject matter, as the mirror of their hearts has been polished through constant repetition and study of poetry, and who sympathetically respond in their own hearts-those (people) are known as sahrdayas-sensitive spectators."

We thus find what place of supremacy pratibha enjoys in the realm of creative literature, one of the fine arts and we might go a step further and assert, in the sphere of all the fine arts.

Contents

| Preface | ||

| 1 | Sanskrit Theory of Beauty | 1-17 |

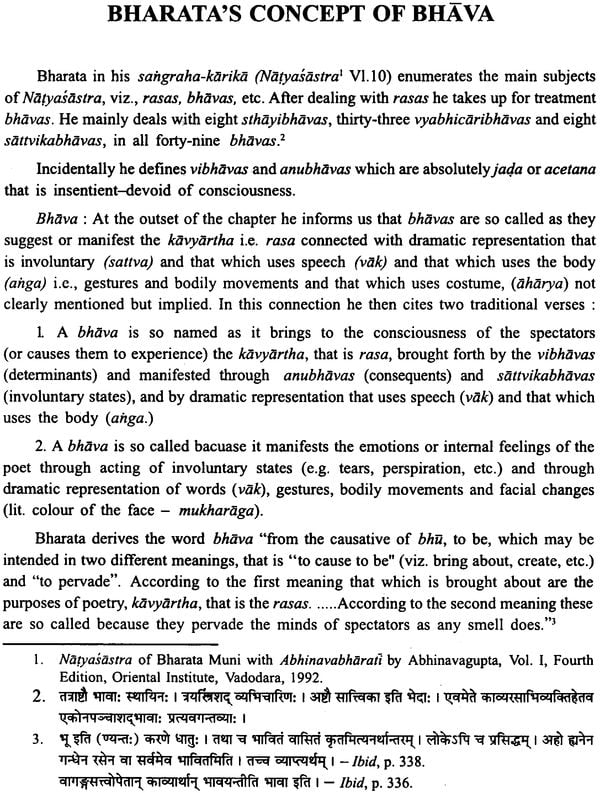

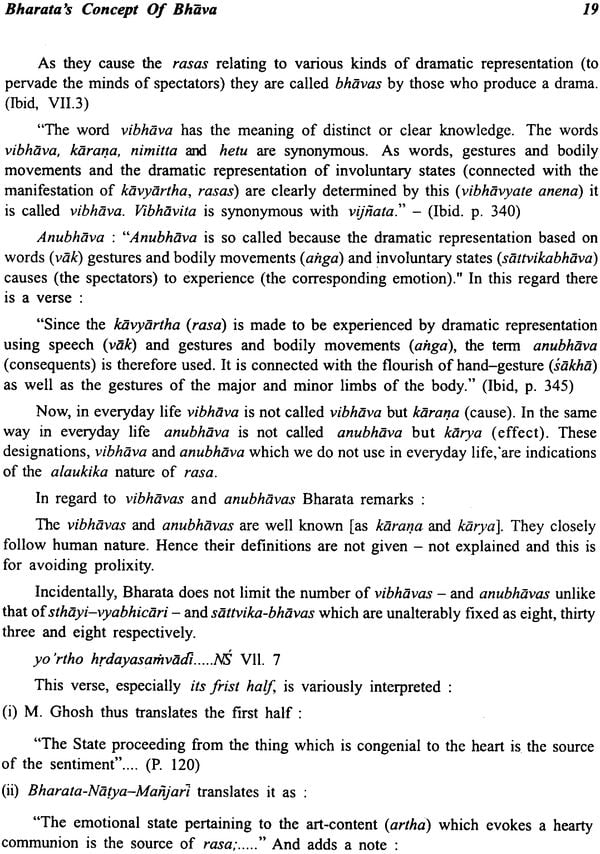

| 2 | Bharata's Concept of Bhava | 18-28 |

| 3 | Dual Nature of Sattvikabhavas | 29-39 |

| 4 | Hemacandra on Sattvikabhavas | 40-45 |

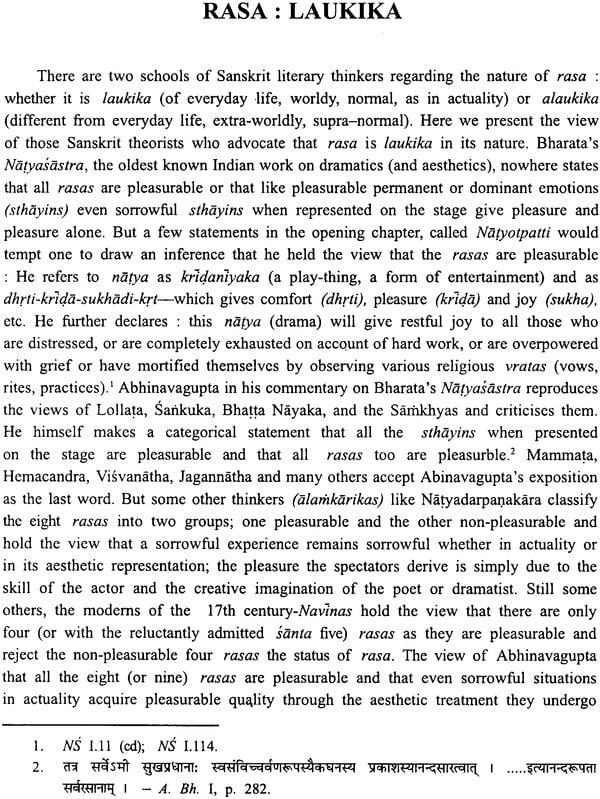

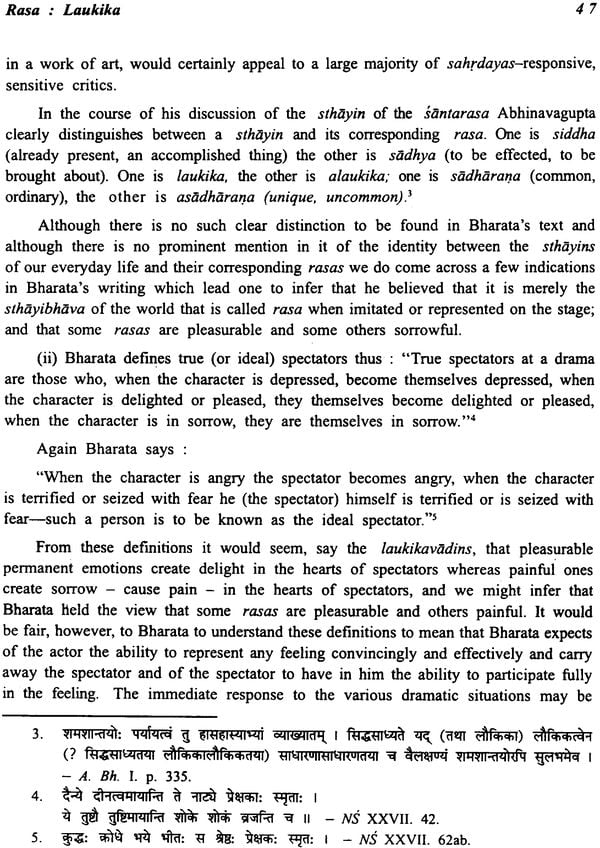

| 5 | Rasa - Laukika | 46-52 |

| 6 | Rasa - Alaukika | 53-68 |

| 7 | Rasa and its Pleasurable Nature | 69-80 |

| 8 | Rasa and its Asraya (Location, Seat) | 81-87 |

| 9 | Rasa Theory and Purusarthas | 88-94 |

| 10 | Mahimabhatta's Views on How Rasas Arise and They are Enjoyed by Sahrdayas | 95-105 |

| Appendix | Prof. M. V. Patwardhan's Translation of Acarya Hemacandra's Section is his Kavyanusasana | |

| (MJV edn. Bombay, 1964) | 06-110 |