गीत वाद्य शास्त्र संग्रह: An Anthology of Ancient Sanskrit Texts on Music

Book Specification

| Item Code: | NZF360 |

| Author: | प्रेमलता शर्मा और मुकुंद लाठ (Premlata Sharma and Mukund Lath) |

| Publisher: | Sahitya Akademi, Delhi |

| Language: | Sanskrit |

| Edition: | 1999 |

| ISBN: | 8126006447 |

| Pages: | 200 |

| Cover: | Hardcover |

| Other Details | 9.0 inch X 6.0 inch |

| Weight | 330 gm |

Book Description

Gita-vadya-sastrasamgrahah is an anthology of Sangita-vadya-sastra (the discipline of music-vocal and instrumental) which has a tradition of more than two millennia. The period becomes larger if we also take sama into account, because the music of sama is as ancient as the Veda itself. The traditions of reciting Vedic mantras, performing yajnas and sama singing have come down to us in an unbroken continuity.

This anthology projects the sastra in all its ramifications as a descriptive and analytical discourse. Gita-vadya-sastrasamgrahah which is unique is its kind invites fresh thinking in the sastra and the section devoted to purvacaryasmaranam shows both a sense of change and continuity in the specialized field.

The compilers of this volume, Dr. Prem Lata Sharma (1972-1998) and Sri Mukund Lath are renowned musicologists. Dr. Prem Lata Sharma had been the Vice chancellor of Indira Kala Sangit Visvavidyalaya, Khairagarh (M.P.). She had won many awards which includes the Sangeet Natak Akademi Award. She had eleven published works to her credit which includes the much acclaimed work Sangeetraja Rana Kumbha. She had been the Vice-chairman of the Sangeet Natak Akademi.

Mukund Lath (1937) grew up in Caluctta studying music with Pt. Maniram, Pt. Ramesh Chakravarty and Pt. Jasarj. He did B.A. (Hons.) in English and move on to Sanskrit. He did his Ph.D. on an ancient text on music published as A Study of Dattilam. He then joined the Department of History and Indian Culture, University of Rajasthan. He has published a number of books and articles on music, theatre, dance as well as history, culture and thought in general. His book Sangita Evam Chintan is a unique attempt to reflect on thought on the analogy of music.

This perhaps is the first anthology prepared under the auspices of the Sahitya Akademi (National Academy of Letters) where the subject matter is a laksana-sastra; all other anthologies published so far pertain to kavya, itihasa, purana etc. which are products of the imagination rather than attempts to theorize about it and analyse and describe it, or in other words, apprehend it discursively. A laksana-sastra attempts to do just that

Sangitasastra has a tradition of analyzing and comprehending music both theoretically and in its various forms of more than two millennia. The period becomes larger if we also take Sama into account, for the music of Sama is as ancient as the Veda itself. Also the enterprise of analyzing, describing and transmitting the music of the Sama is as old as similar enterprises for the Vedic mantra. Also like the traditions of reciting Vedic mantras and performing yajnas, the traditions of Sama singing, too, have come down to us in an unbroken continuity.

But the world of Sama is a world in itself. In this anthology we have not tried to enter this world except peripherially. The reason is two-fold. Form a musicological point of view, Sama remains largely an unchartered area, both formally and historically. The little mapping of the area that has been done is inadequate for us to be able to place it in the larger map of Indian music and musical tradition in general. Sama also has a rich sastraic tradition of its own. This tradition has not yet become a familiar territory for the musicologist. The history of this sastra, the nature of its discourse, it s relation with the laksya, the Sama, remain vague to us as musicologists. An independent scholarly enterprise is needed to charter this territory before one can even think of making a samgraha of it.

But though distinct from the sangita which is a envisaged in this samgraha, Sama has been a source of inspiration for what might be called the jati and raga tradition in many ways. The sastra itself speaks of these connections which, as can be seen from our samgraha, is both formal and historical. Gandharva has been spoken repeatedly as being born of Sama. Many of its specific elements are directly related to the specific elements in Sama.

The greatest importance of Sama lies in the great sanctity it bestows on music. Sama is perhaps the only example of a revelation which has expressed itself in the form of music. The Vedic mantra, that is the text to which the Sama is sung, is revealed independent of the Sama. Indeed, in the Sama tradition, when Sama became an upasana there was a tendency to devalue the rk (as our quotation from the Jaiminiya Brahmana, show…) and make music a transcendental object in itself.

The snactity which Sama gave to music has served it well in musical history. It could be brought to the defence of music as an art when such a defence was needed (see our section on Sangita Prasamsa).

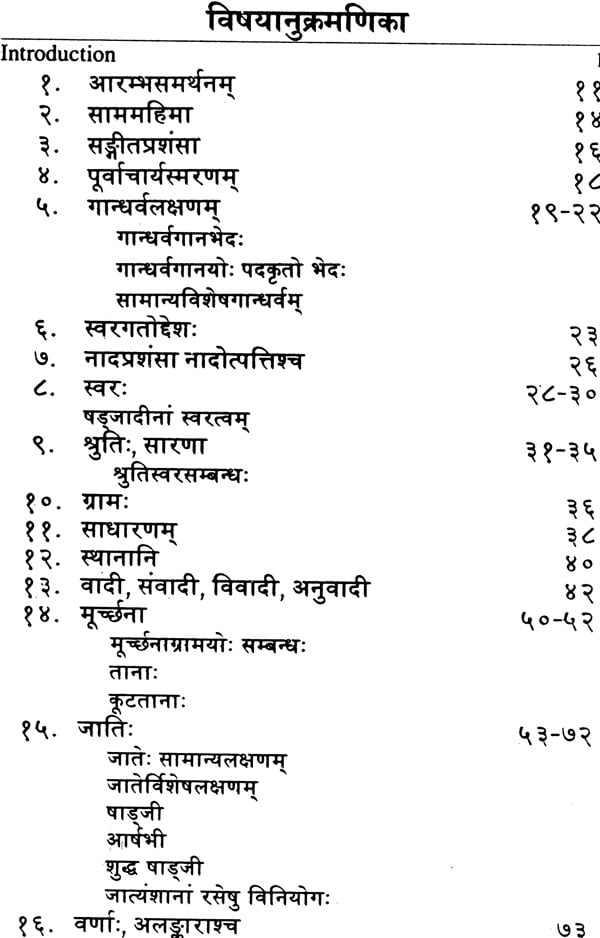

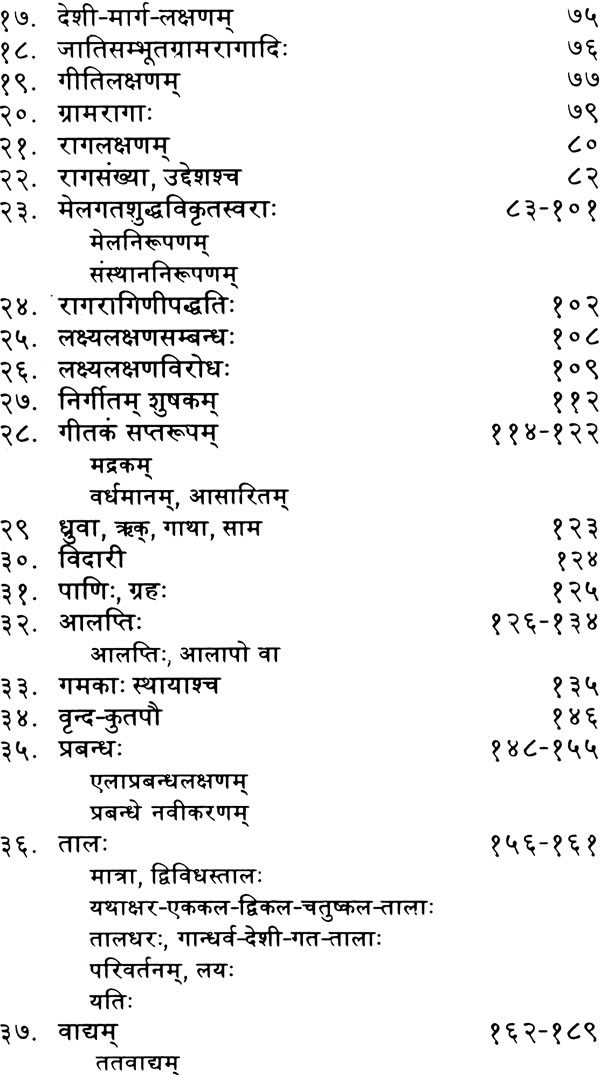

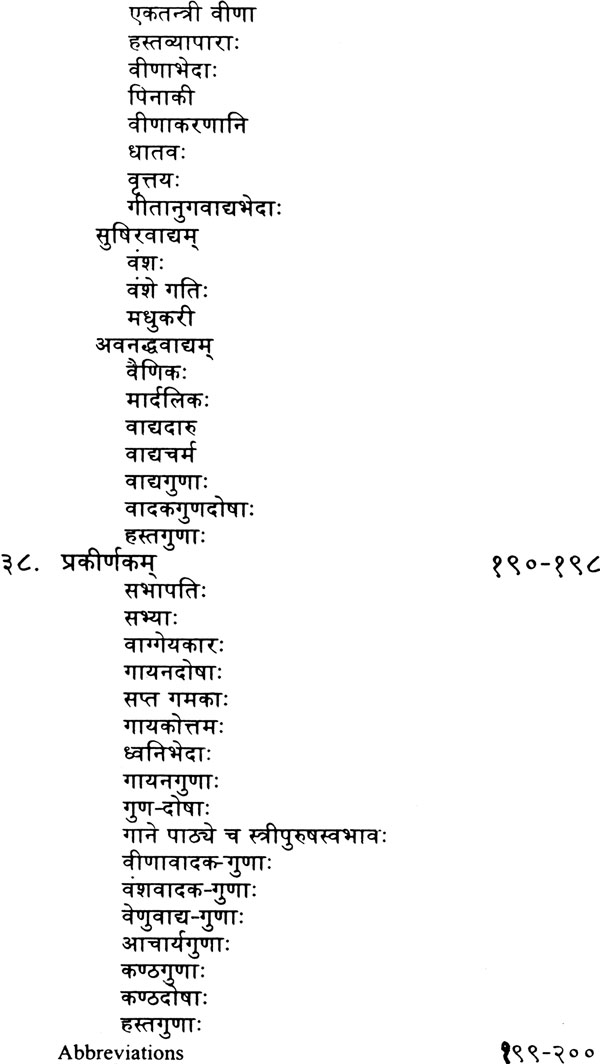

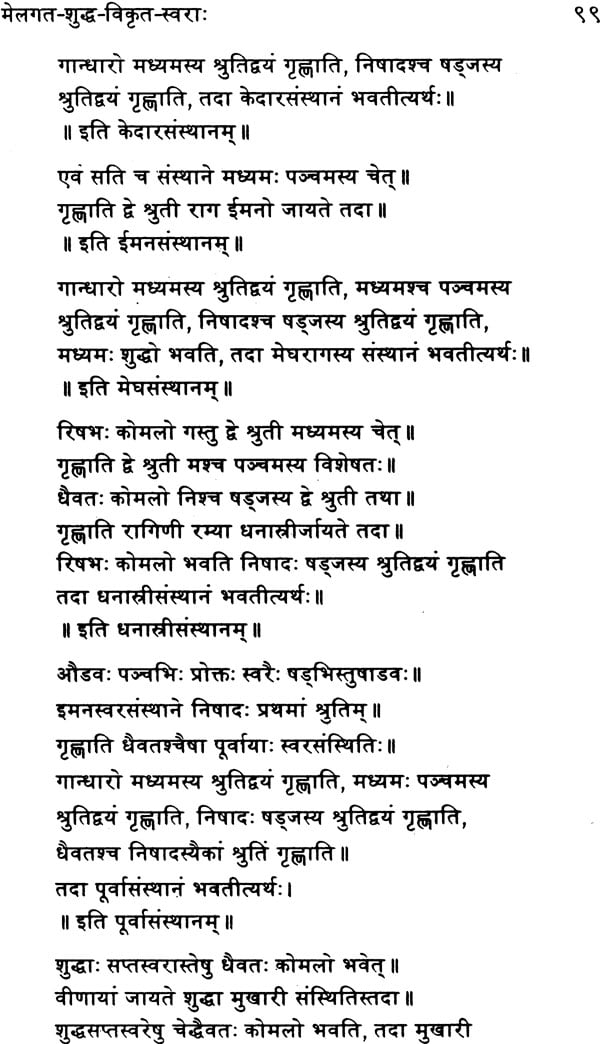

The plan of our samgraha is, we think, displayed in our chapterization itself. These we have called vidaris, borrowing a term from music, a term which deserves to be used more often than it is. We have tried to amalgamate two distinct principles: the formal or logical and the chronological or historical. We have tried to project the sastra in all its ramifications as a descriptive and analytical discourse. But the sastra has been a growing and changing sastra in an inherent sense, since the laksya, music, has itself grown and changed. Thus our samgraha takes into account this fundamental historicity of its discourse. Indeed the sastra shows great self –awareness of its historical nature even while maintaining a continuity which sometimes might appear forced and unnatural. Our chapter devoted to fresh thinking in the sastra and the section devoted to purvacarya-smarnam shows both a sense of change and continuity.

What does not-and cannot- be reflected in a samgraha of this kind is –(i) the great amount of repetition with which much of the sastra is overladen, (ii) the role of individual sastris in the formation and formulation of the sastra, both as theorists and stylists. Great individuals, such as Abhinavagupta, Sarngadeva, Venkatamakhin and Somanatha among others do not stand out as great figures as they ideally should.

It should also be remembered that sangita as a descriptive discourse tends to be very technical and specialized, weaving a large web which captures its laksya to whatever degree it can only as a totality. We have perforce had to break this totality and select items to suit our purpose and design.

To whom are we addressing this samgraha is a question that we have asked ourselves again and again. We are really not sure. Students of this sastra are rare and few even among the growing tribe of musicologists. Such students would in any case enter the sastra through a standard text rather than a samgraha as would be wise enough. Who, then, do we have in mind as our readers? There is, happily, a growing number of people who are interested in a comparative and historical study of intellectual history and theory who, we hope, could be initiated into this sastra through our samgraha. Indeed this samgraha would have served its purpose if it arouses interest in an appreciation of this sastra as a major intellectual discipline.