Chan Heart, Chan Art

Book Specification

| Item Code: | NAM800 |

| Author: | Venerable Master Hsing Yun |

| Publisher: | Buddha Light Art and Living Pvt Ltd |

| Language: | English |

| Edition: | 2012 |

| ISBN: | 9789382017158 |

| Pages: | 236 (Throughout Color Illustrations) |

| Cover: | Paperback |

| Other Details | 11.0 inch X 8.5 inch |

| Weight | 700 gm |

Book Description

Chan Heart, Chan Art is a unique volume that pairs one hundred traditional Chan (Zen) stories retold by a modern Chinese master with one hundred painting that beautifully capture the flavour of traditional art. Venerable Master Hsing Yun, founder of the Fo Guang Shan Buddhist Order, offers an account of the teaching of ancient Chan masters who have awakened to the Buddha's truth through the cultivation of their minds, and in turn, inspired countless students to pursue Chan study. To make these lessons more accessible to today's readers Master Hsing Yun has written commentaries at the end of each story to elucidate the meaning of difficult gongans (koans) and gathas (verses). The accompanying portraits, painted by the renowned husband-and-wife team, Gao Ertai and Pu Xiaoyu, visually transmit the profound expressions of Chan.

This volume includes supplementary material aimed at enriching the experience of the reader and guiding them towards a deeper 7understanding of Chan. A biographical section has been appended to the stories to provide a historical context to the lives of the notable Chan masters and students who appear in. The section of endnotes further explains key Buddhist terms, cultural references, and the layers of meaning alluded to in the original Chinese text.

Founder of the Fo Gauang Shan (Buddha's Light Mountain) Buddhhist Order and the Buddha's Light International Association, Venerable Master Hsing Yun has dedicated his life to teaching Humanistic Buddhism, which seeks to realize spiritual cultivation in everyday ling.

Master Hsing Yun is the 48th Patriarch of the Linji Chan School. Born in Jiangsu Province, China in 1927, he was tonsured under Venerable Master Zhikai at the age of twelve and became a novice monk at Qixia Vinaya College. He was fully ordained in 1941 following years of strict monastic training. When he left Jiaoshan Buddhist College at the age of twenty, he had studied for almost ten years in a monastery.

Due to the civil war in China, Master Hsing Yun moved to Taiwan in 1949 where he undertook the revitalization of Chinese Mahayana Buddhism. He began fulfilling his vow to promote the Dharma by starting chanting groups, student and youth groups, and other civic-minded organizations with Leiyin Temple in Ilan as his base. Since the founding of Fo Guang Shan monastery in Kaohsiung in 1967, more than two hundred temple have been established worldwide. Hsi Lai Temple, the symbolic torch of the Dharma spreading to the West, was built in 1988 near Los Angeles.

Master Hsing Yun has been guiding Buddhism on a course of modernization by integrating Buddhist values into education, cultural activities, charity, and religious practices. To achieve these ends, he travels all over the world, giving lectures and actively engaging in religious dialogue. The Fo Guang Shan organization also oversees sixteen Buddhist colleges and four universities, one of which is the University of the West in Rosemead, California.

Xiaoyu and I painted these one hundred Chan paintings three years ago in Los angeles at the request Venerable Master Hsing Yun. When we first arrived in the United States, we had no family or friends, and not so much as a single penny, we were extremely grateful to Venerable Master Hsing Yun for providing us with an opportunity to earn our own living allowing us to pave the way for a new life through our own efforts. At the time, we had two opportunities: one was to go to Harvard University as visiting scholars; the other was to go to Hsi Lai Temple to work on these paintings. We chose the latter. This first choice we made upon initially arriving in the United State determined our life's course for many years afterwards.

Out of gratitude to Venerable Master Hsing Yun, we worked extremely hard night and day, completing these one hundred paintings within half a year. During this time, because several publications were urgently asking for my manuscripts, had no choice but to spend a great deal of time on them. Therefore, these paintings are mostly Xiaoyu's own compositions. She worked Museum for ten years copying ancient paintings, which is reflected in the strong traditional aura of these paintings.

Although the specifications and dimensions of the one hundred paintings are the same, each one has an independent theme. For this reason, we dedicated ourselves to giving the appearance of each character distinctive features, and did our very best not to make them similar. Avoiding duplication in one hundred paintings with one hundred paintings with one hundred compositions and hundred of characters is really not easy. Particularly since monastic's wear identical attire, only in the characteristics of the facial features and expressions could we eek variation. The degree of difficulty was even greater when conforming to the laws of human anatomy because we could only seek variation within the scope of artistic composition and proportion. If the readers can see in these one hundred paintings that every composition is different and the appearance of very character is distinct, then we will feel deeply contented.

There is a tradition in Chinese portrait painting that seeks to "accomplish social education and advocate human ethic." Frequently, it transforms words into a concrete and tangible form. For the two of us, the process of painting these works was propagating the Dharma as well as studying the Dharma. The source for the subject matter of these paintings is the four-volume Hsing Yun's Chan Talk. These four books not only present the vast wisdom of ancient Chan masters, but also the profound wisdom of Venerable Master Hsing Yun. Passing them on to the reader with the paintbrush is also kind of meritorious deed. It with this spirit that we offer all of these paintings to the readers.

The verses inscribed on the paintings were provided by Hsi Lai Temple and are not work. We wish to make this clear and do not claim credit for them.

All Buddhist teaching begin with a teacher and a student, and the instruction Venerable Master Hsing Yun offers us in this collection of Chan stories between masters and disciples is no exception. These are stories about self-awakenings: Chan masters who awakened to the Buddha's truth through the cultivation of their, minds, and in turn, inspired countless students to practice Chan. The literature behind these teachings flows directly from the old master's metaphors of the Buddha's realization, and is not necessarily history as conventionally conceived. Like all human experience, the history of Chan is mostly unrecorded in books. The significance of these stories lies not in the events of the past, but in their effect on the students of the Way.

Chan was rooted in China by Bodhidharma, who traveled from India in the sixth century, and was then carried eastward to Japan in the twelfth century. By our worldly understanding, the Chan sages lives in a time and context so far removed from our own experience that we risk dismissing their wisdom outright, yet Chan is no less relevant today than it was in ancient China. It remains important precisely because the enlightenment of the historical Buddha and his Chan descendants does not depend on external cultural or social conditions so much upon the state of the mind within us.

The Chan mind, the masters teach us, cannot be sought outside. Where then, can we find the mind? Venerable Master Hsing Yun recounts an encounter between Chan Master Nanyue Huairang and his teacher Songshan An to break through this very point:

One day, Chan Master Nanyue Huairang of the Tang Dynasty paid a visit to Chan Master Songshan An and asked him, "What is the meaning of the patriarch coming to the West?"

Huairang then asked, "What is the meaning of self?"

Songshan An replied, "Pure contemplation and wondrous function."

Huairang inquired, "What is the wondrous function?"

Chan Master An instructed him by opening and closing his eyes. At that moment, Huairang had a great awakening.

It is our physical eyes which perform the actions of opening and closing, but it is our it is our true mind which given commands. At every moment, our true mind is not separate from us; most of the time, we obscure is. What we must do to become aware of the mind is to examine and investigate it directly.

Cahn Heart, Chan Art is a volume that attempts to penetrate to the very heart of Chan by directly demonstrating how the Chan life is as relevant to the casual reader as to the practitioner. Venerable Master Hsing Yun's approach is to let the Chan tradition speak for itself. In our translation, Dana and I have respected the Master's style of teaching by preserving the essential spirit of this words in order to fully capture the "flavour of Chan." He is the teacher and we are the students. For this reason, we have avoided providing our own interpretations and have, instead, allowed our translation to flow in the current of his words. The supplementary material appended to the stories is aimed at enriching the experiences of the readers and guiding them towards a deeper understanding of Chan. The section of explanatory notes explains key Buddhist terms, cultural references, and the layers of meaning alluded to in the original Chinese text. The biographical section provides a historical context to the lives of the notable Chan teachers and students who appear in the book.

In the last two years, working with Dana has profoundly deepened my awareness of cultivating the mind through translation. From moment to moment, he manifested Chan through the simple acts of listening to others and respecting others. For Dana, the experience of translating of translating the Chan exchanges between masters and students was just another opportunity to speak Chan words, hear Chan sound, so Chan deeds, and cultivate the Cahn mind. It was by his example that the seeds of the Buddha's teaching began to take root in my life.

It can be said that the Buddha us to reflection on the fact we do not have forever to cultivate the mind. The same thing is true of Chan practice. It is not practice; it is your life in every moment May you experience the living heart of Chan and awaken to your own true Chan mind.

Contents

| What Is Chan? | i |

| Foreword By The Artist | iii |

| Translator's Introduction | iv |

| Acknowledgements | vi |

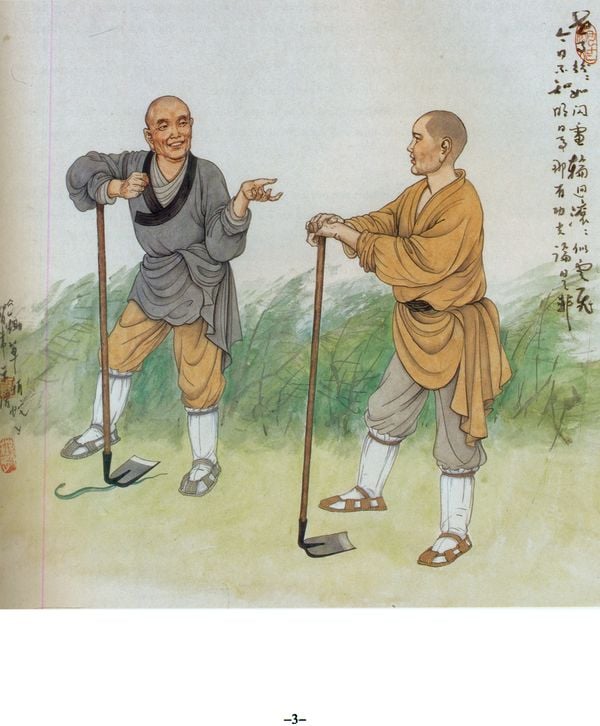

| Hoe The Weeds, Chop The Snake | 2 |

| The Moon Cannot Be Stolen | 4 |

| Transcend The Ordinary And The Sacred | 6 |

| One And Ten | 8 |

| Not Changing Responds To Myriad Changes | 10 |

| Not Believing Is The Ultimate Truth | 12 |

| I'm Not A Sentient Being | 14 |

| Cannot Take Your Place | 16 |

| Let Go Of What? | 18 |

| Arrive At Longtan | 20 |

| I'm An Attendant | 22 |

| The Manifestation of Manjusri | 24 |

| I'm Here | 26 |

| Help Yourself With Your Own Umbrella | 28 |

| Mind And Nature | 30 |

| How Heavy | 32 |

| High And Far | 34 |

| Nightly Wanderings | 36 |

| I Can Be Busy For You Too | 38 |

| Antique Mirror Not Polished | 40 |

| How Was It Ever Confused? | 42 |

| Dadian And Han Yu | 44 |

| Extinguish The Fire In One's Mind | 46 |

| A Model Through The Ages | 48 |

| Hundred Years, One Dream | 50 |

| Space Winks | 52 |

| Aspects Of Life | 54 |

| No Merit At All | 56 |

| The Imperial Master And The Emperor | 58 |

| Originally Empty Without Existence | 60 |

| What Are Lice Made Of? | 62 |

| Can't Be Snatched Away | 64 |

| The Way To Receive Guests | 66 |

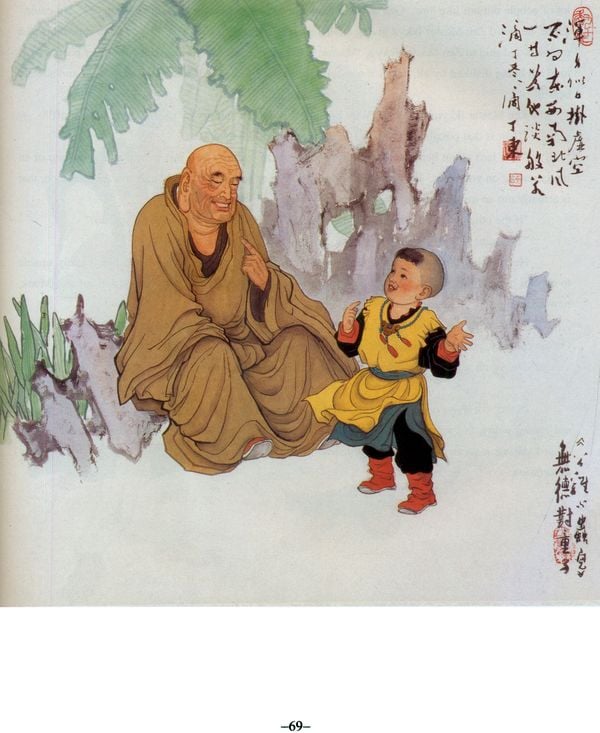

| The Rooster And The Bug | 68 |

| Do Not Wipe It Off | 70 |

| The Beggar And Chan | 72 |

| Original Face | 74 |

| The Chan In The And Meals | 76 |

| Pick Up A Little More | 78 |

| One Sitting, Forty Years | 80 |

| A Poem | 82 |

| Happiness And Suffering | 84 |

| Self-Liberating Person | 86 |

| A Place For Living In Seclusion | 88 |

| Huike's Settled Mind | 90 |

| Treasure The Present | 92 |

| Speaking Of The Supreme Dharma | 94 |

| The Most Charming | 96 |

| Like Cow Dung | 98 |

| Abnormal | 100 |

| Question And Answer In The Chan School | 102 |

| Niaoke And Bai Juyi | 104 |

| The Eight Winds Cannot Move Me | 106 |

| A Mind Without The Way | 108 |

| Poems And Gathas Debate The Way | 110 |

| I Want Eyeballs | 112 |

| Flowing Out From The Mind | 114 |

| Big And Small Have No Duality | 116 |

| Revere The As A Buddha | 118 |

| Close The Door Properly | 120 |

| Let Go! Let Go! | 122 |

| No Time To Feel Old | 124 |

| A Monastic Robe | 126 |

| No Room For The Ordinary Mind | 128 |

| The Universe As My Bed | 130 |

| Tone Of Voice | 132 |

| Better Silent Than Noisy | 134 |

| Grass And Trees Become Buddhas | 136 |

| Where Are You From? | 138 |

| The Buddhas Do Not Lie | 140 |

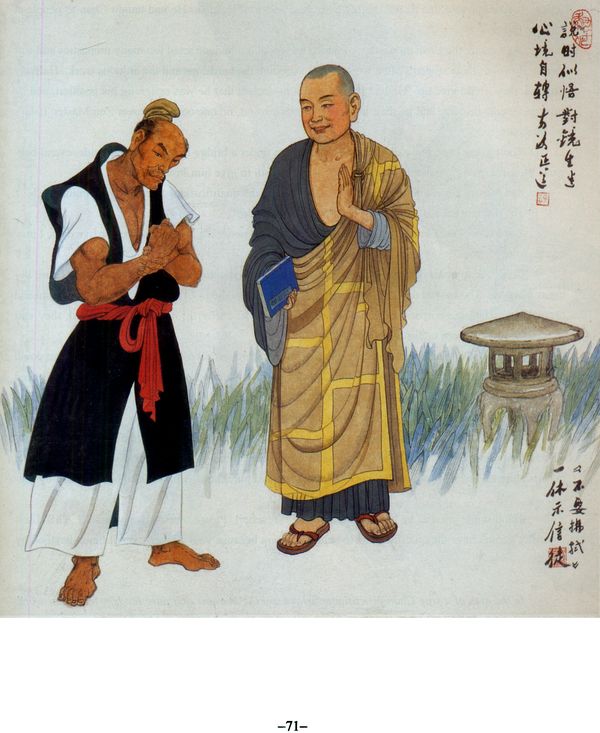

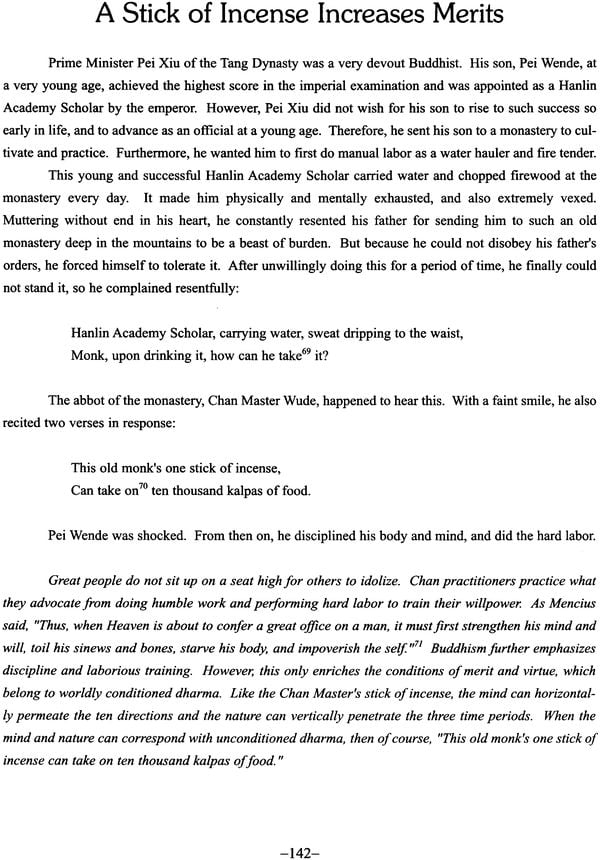

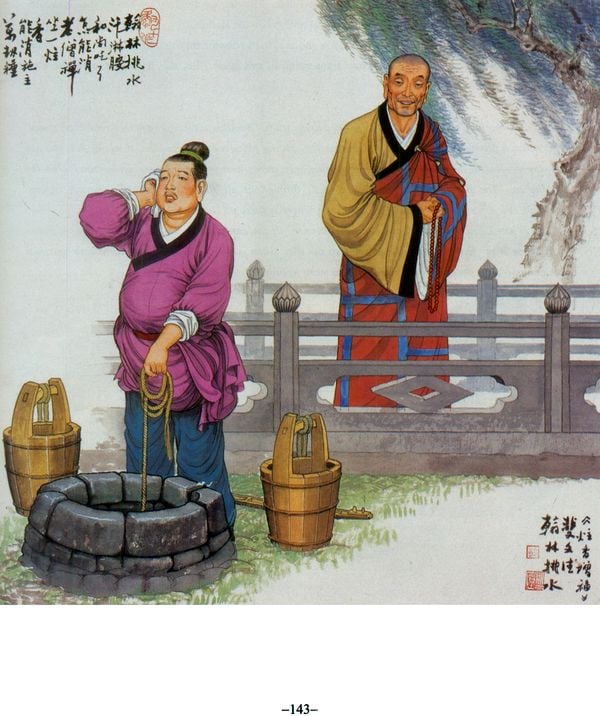

| A Stick Of Incense Increases Merits | 142 |

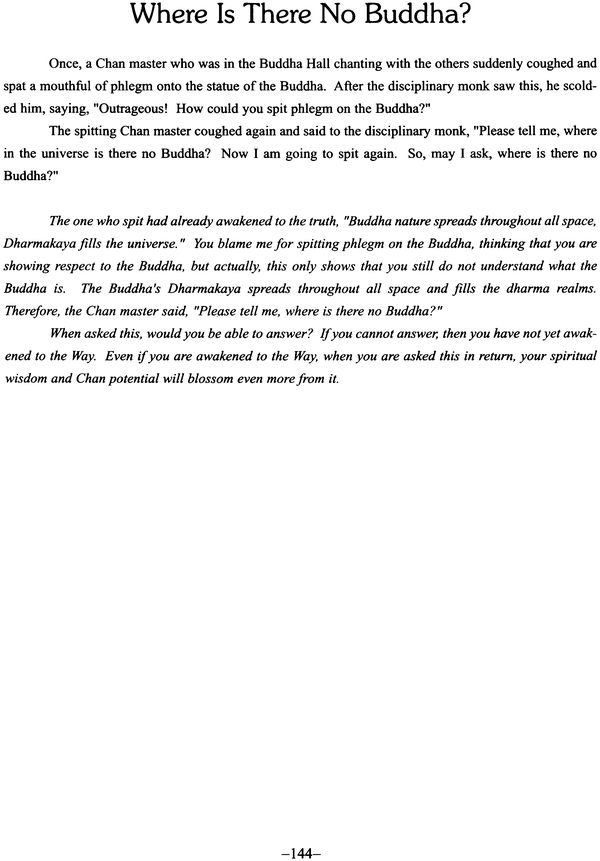

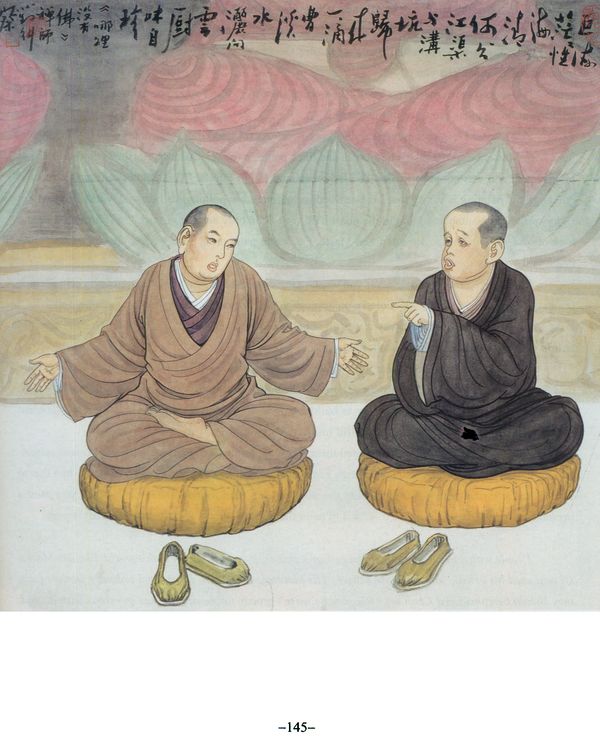

| Where Is There No Buddha? | 144 |

| Never Paint Again | 146 |

| The Wondrous Application Of Chan | 148 |

| Doing Evil And Cultivating Goodness | 150 |

| Short-Tempered By Nature | 152 |

| Where Can We Abide In Peace? | 154 |

| The Heart Of Chan | 156 |

| Like An Insect Eating Wood | 158 |

| Is It Crooked? Is It Upright? | 160 |

| Can't Tell You | 162 |

| Drying Mushrooms | 164 |

| Fly Beyond Birth And Death | 166 |

| Not Permitted To Be A Teacher | 168 |

| Not Even A Thread | 170 |

| Wild Fox Chan | 172 |

| Reform The Self | 174 |

| I Don't Know | 176 |

| The Whole Body Is The Eye | 178 |

| The Way Of Nurturing Talent | 180 |

| Everything Is Chan | 182 |

| Cutting Off Ears To Save The Pheasant | 184 |

| One And Two | 186 |

| Honesty Without Deception | 188 |

| A Taste Of Chan | 190 |

| Transferring Merits | 192 |

| Purify The Mind, Purify The Land | 194 |

| Salty And Plain Have Flavor | 196 |

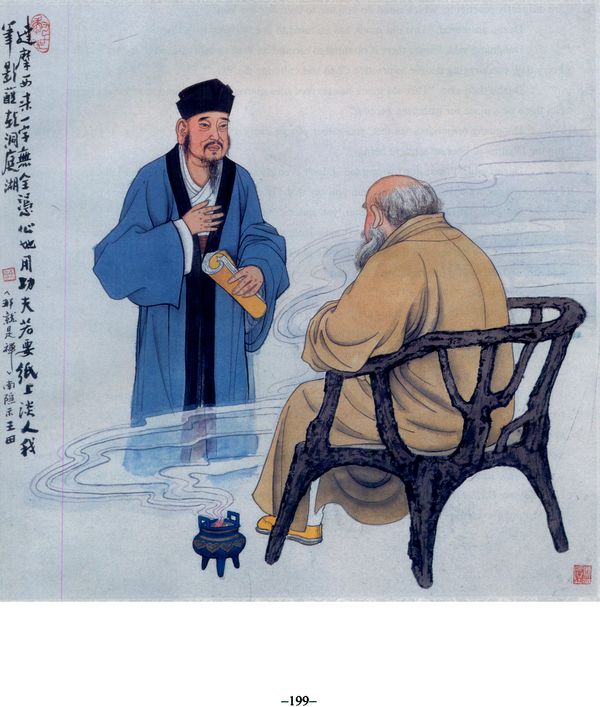

| That Is Chan | 198 |

| True And False-Deluded Words | 200 |

| Explanatory Notes | 202 |

| Glossary Of Buddhist Terms | 205 |

| Biographies Of The Chan Masters | 213 |

| Biographies Of Other Noteworthy People | 220 |