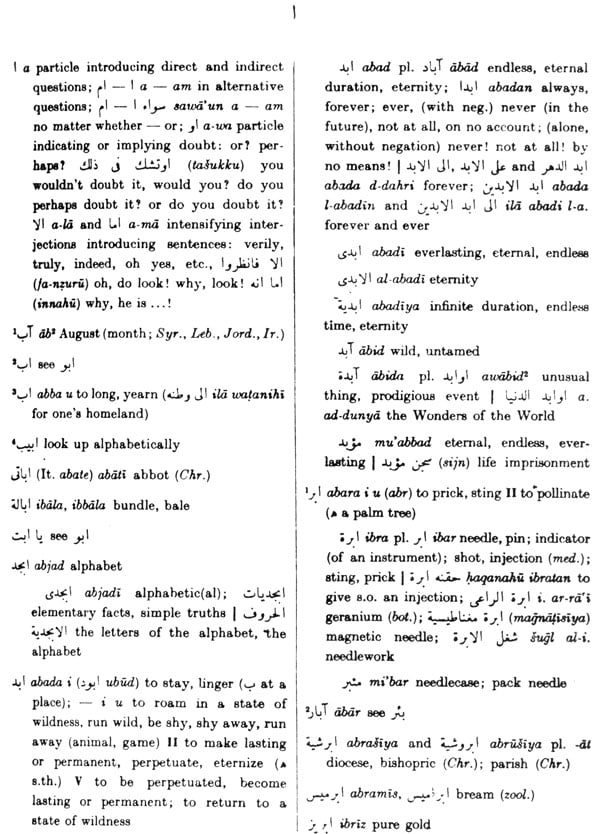

A Dictionary of Modern Written Arabic

Book Specification

| Item Code: | NAH248 |

| Author: | Hans Wehr Edited by: J. Milton Cowan |

| Publisher: | Kitab Bhavan |

| Language: | Arabic Text with English Translation |

| Edition: | 1974 |

| Pages: | 1118 |

| Cover: | Hardcover |

| Other Details | 9.0 inch X 6.0 inch |

| Weight | 1.10 kg |

Book Description

Preface

Shortly after the publication of Professor Hans Wehr’s Arabisches Worterbuch fur die Schriftsprache der Gegenwart in 1952, the Committee on Language Programs of the American Council of Learned Societies recognized its excellence and began to explore means of providing an up-to-date English edition. Professor Wehr and I readily reached agreement on a plan to translate, edit, and enlarge the dictionary. This task was considerably lightened and hastened by generous financial support from the American Council of Lerned Societies, the Arabian American Oil Company, and Cornell University.

This dictionary will be welcome not only to English and American users, hut to orientalists throughout the world who are more at home with English than with German. It is more accurate and much more comprehensive than the original version, which was produced under extremely unfavorable conditions in Germany during the late war years and the early postwar period.

Introduction

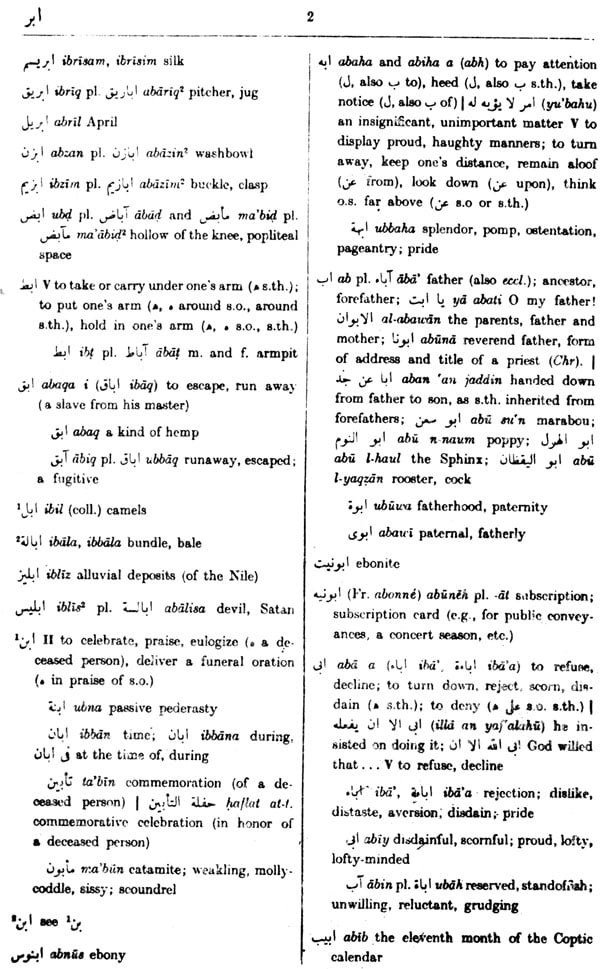

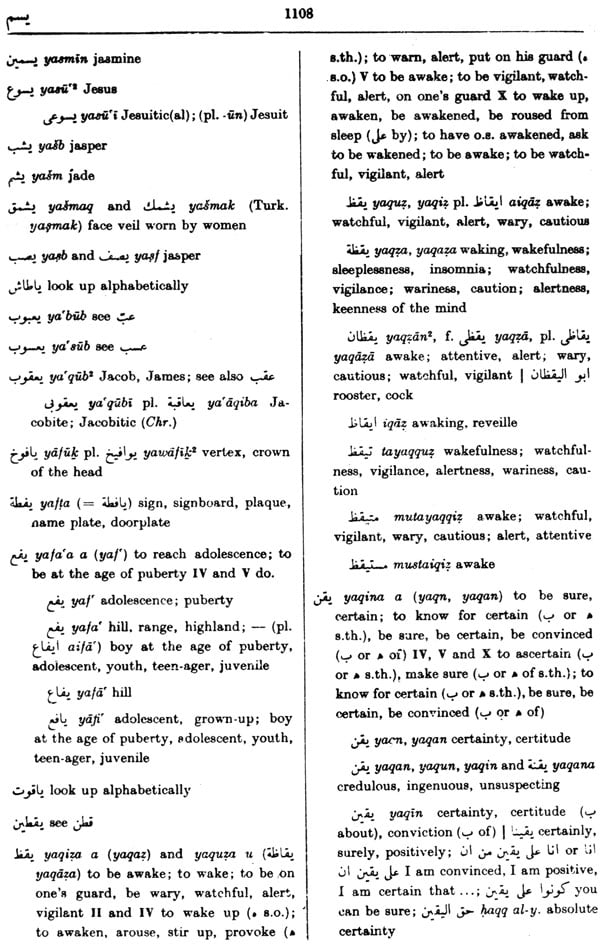

This dictionary presents the vocabulary and phraseology of modem written Arabic. It is based on the form of the language which, throughout the Arab world from Iraq to Morocco, is found in the prose of books, newspapers, periodicals, And letters. This Corm is also employed in formal public address, over radio and television, and in religious ceremonial. The dictionary will be most useful to those working with writings that have appeared since the turn of the century.

The morphology and syntax of written Arabic are essentially the same in all Arab countries. Vocabulary differences are limited mainly to the domain of specialized vocabulary. Thus the written language continues, as it has done throughout centuries of the past to ensure the linguistic unity of the Arab world. It provides a medium of communication over the vast geographical area whole numerous and widely diverse local dialects it transcends. Indeed, it gives the Arab people of many countries a sense of identity and an awareness of their common cultural heritage.

Two powerful and conflicting forces have affected the development of the modern Arabic lexicon. A reform movement originating toward the end of the last century in Syria and Lebanon has reawakened and popularized the old conviction of educated Arabs that the ancient arabiya of pre-Islamic times, which became the classical form of the language in the early centuries of Islam, is better and more correct than any later form. Proponents of this puristic doctrine have held that new vocabulary must be derived exclusively in accordance with ancient models or by semantic extension of older Corms. They have insisted on the replacement of all foreign loanwords with purely Arabic Corms and expressions. The purists have had considerable influence on the development of modern literary Arabic although there has been widespread protest against their extreme point of view. At the same time and under the increasing influence of Western civilization, Arab writers and journalists have had to deal with a host of new concepts and ideas previously alien to the Arab way of life, As actual usage demonstrates, the purists have been unable to cope with the sheer bulk of new linguistic material which has had to be incorporated into the language to make it current with advances in world knowledge. The result is seen in the tendency of many writers, especially in the fields of science and technology, simply to adopt foreign words from the European languages. Many common, everyday expressions from the various colloquial dialects have also found their way into written expression.

From its inception, this dictionary has been compiled on scientific descriptive principles. It contains only words and expressions which were found in context during the course of wide reading in literature of every kind or which, on the basis of other evidence, can be shown to be unquestionably a part of the present-day vocabulary. It is a faithful record .of the language as attested by usage rather than a normative presentation of what theoretically ought to occur. Consequently, it not only lists classical words and phrases of elegant rhetorical style side by side with new coinages that conform to the demands of the purists, but it also contains neologisms, loan translations, foreign loans, and colloquialisms which may not be to the linguistic taste of many educated Arabs. But since they occur in the corpus of material, on which the dictionary is based, they are included here.

A number of special problems confront the lexicographer dealing with present-day Arabic. Since for many fields of knowledge, especially those which have developed outside the Arab world, no generally aceepted terminology has yet emerged, it is evident that a practical dictionary eau only approximate the degree of completeness found in comparable dictionaries of Western languages. Local terminology, especially for many public institutions, offices, titles, and administrative affairs, has developed ill the several Arab countries. Although the dictionary is based mainly on usage in the countries bordering on the eastern Mediterranean, local official and administrative terms have been included for all Arab countries, but not with equal thoroughness. Colloquialisms and dialect expressions that have gained currency in written form also vary from country to country. Certainly no attempt at completenees can be made here, and the user working with materials having a marked regional flavor will be well advised to refer to an appropriate dialect dictionary or glossary. As a rule, items derived from local dialects or limited to local use have been 80 designated with appropriate abbreviations.

A normalized journalistic style has evolved for factual reporting of news or discussion of matters of political and topical interest over the radio and in the press. This style, which often betrays Western influences, is remarkably uniform throughout the Arab world. It reaches large sections of the population daily and constitutes to them almost the only stylistic norm. Its vocabulary is relatively small and fairly standardized, hence easily covered in a dictionary.

The vocabulary of scientific and technological writings, on the other hand, is by no means standardized. The impact of Western civilization has confronted the Arab world with the serious linguistic problem of expressing a vast and ever-increasing number of new concepts for which no words in Arabic exist. The creation of a scientific and technological terminology is still a major intellectual challenge. Reluctance to borrow wholesale from European languages has spurred efforts to coin terms according to productive Arabic patterns, in recent decades innumerable such words have been suggested in various periodicals and in special publications. Relatively few of these have gained acceptance in common usage. Specialists in all fields keep coining new terms that are either not understood by other specialists in the same field or are rejected in favor of other, equally short-lived, private fabrications.

The Academy of the Arabic Language in Cairo especially, the Damascus Academy, and, to a lesser extent, the Iraqi Academy have produced and continue to publish vast numbers of technical terms for almost all flelds of knowledge. The academies have, however, greatly underestimated the difficulties of artificial regulation of a language. The problem lies not 80 much in mventing terms as it does in assuring that they gain acceptance. In some instances neologisms have quickly become part of the stock of the language; among these. fortunately, are a large number of the terms proposed by academies or by professional specialists. However, in many fields, such as modern linguistics, existential philosophy, or nuclear physics, it is still not possible for professional people from the different Arab states to discuss details of their discipline in Arabic. The situation is further complicated by the fact that the purists and the academies demand the translation into Arabic even of those Greek and Latin technical terms which make possible international understanding among specialists. Thus while considerable progress has been made in recent decades toward the standardization of Arabic terminology, several technical terms which all fit one definition may still be current, or a given scientific term may have different meanings for different experts.