Folk Festivals and Beliefs of Radh Bengal- Understanding Through Ethnoarchaeology

Book Specification

| Item Code: | UAD759 |

| Author: | Lopamudra Maitra Bajpai |

| Publisher: | Kaveri Books |

| Language: | English |

| Edition: | 2022 |

| ISBN: | 9788174792426 |

| Pages: | 280 (Throughout B/W Illustrations) |

| Cover: | HARDCOVER |

| Other Details | 9.00 X 6.00 inch |

| Weight | 620 gm |

Book Description

This publication explores various folk festivals, rites, rituals, beliefs and oral traditions to understand the many processes that went into creating a unique identity of the area of study - the Radh region of Bengal. The work has been supplemented with intensive ethnographic fieldwork across the region, supplemented by available archaeological findings, records and publications. Forming the western part of the state of West Bengal (India), the present study focuses on the districts of Purulia, Bankura and Paschim Mednipur (West Mednipur) and is a representative of understanding a continuous process of historical development to look into settlement patterns, migrations and resettlements, geographical boundaries, royal patronages of festivals and beliefs and oral traditions, reflecting ideas and identities.The local characteristics of these also helps to connect the area to the larger picture of the region and also brings to context a historical understanding with the bigger part of India. The fieldwork undertaken, was intensive enough in nature and looks into rural communities, which have undergone important processes of assimilation of thought processes and ideas, rendering them a distinct identity.

The present publication will be of interest to not only common readers, but anybody who wants to look into the study of history, archaeology, anthropology of Bengal, eastern India, ethnography, religious studies, folk culture, folk festivals, oral history and traditions.

Dr. Lopamudra Maitra Bajpai is a Visual Anthropologist, author and international columnist, her interests include - history, popular culture and communication and intangible cultural heritage (ICH and oral history) of India and South Asia. She lectures at Symbiosis International (Deemed) University, India. She has been a Culture Specialist (Research) at SAARC Cultural Centre, Colombo, Sri Lanka, a Research Grant Fellow (Indian High Commission, Sri Lanka) and an Assistant Professor at Symbiosis International (Deemed) University, Pune (India). She is also on the editorial board of several international journals and has also been a Guest Editor for Nidan- International Journal of Indian Studies- of University of Kwa-Zulu Natal, Durban, South Africa (2020-2022) for the issues on South Asian Folklore.

The Radh region of West Bengal presents an interesting blend of thought processes and beliefs, expanding over an extensive geographic region which is an extension of the Bihar Chhotanagpur plateau and is comprised of red laterite soil. This study concentrates on three specific districts of Purulia, West Mednipur and Bankura, which celebrate various ceremonies, festivals, melas as well as rites and rituals that represent an interesting medley of what might be considered an orthodox Brahmanical tradition on one hand and an unorthodox folk tradition on the other. With limited historical and archaeological records, it becomes difficult to weave a continuous trend of representation of sociocultural and religious aspects of life in the region. However, certain information from archaeology as well as history, supplemented as well as complimented by folk traditions as well as specifically observed rites and rituals, help to understand the ethos of the existence of a major part of the socio-religious life in the region. These ceremonies form an important part of the lives of the autochthones or vratyas who reside in the region of study. Interestingly enough, these autochthones were not originally agriculturists and are referred to as belonging to so-called lower castes and so-called upper castes of the region even in present times, with several such instances evident throughout various historical and literary records as well. The section of the population in the region- referred to as the so-called upper castes- are also mentioned in various historical and literary records to have migrated from outside the region, who gradually and over a period of time, absorbed the non-agriculturist locals as hired labours under them in their agrarian activities. The geo-physical aspect of their habitation also varies between the relatively woodlands of the tribal population with a subsistence pattern of fishing, hunting, etc. to the plain regions with agriculturists, pastorals and other antyaja groups. Evidences of hired labourers in agrarian fields were also prominent during the course of the field-work with many people from such classes as the Bauris, Lohars, Lodhas, Bagdis, Kayet and others working as hired labours in the fields of landed agriculturists, who evidently belonged to the so-called upper castes, including Brahmans, Kayasthas, Rajputs and others. The stories of such immigration of the so-called upper castes were also prominent through oral traditions during the course of study. It should be mentioned here that the oral traditions help to justify up to a certain extent the social association between the State of West Bengal and neighbouring states. Thus, these traditions help to highlight the significant aspect of social, cultural and religious similarities between the region of study and Odisha as well as parts of Bihar and Jharkhand. The connection between cultures is also corroborated by various historical facts, which testify the region to have been closely associated and connected to Odisha as well as Bihar, besides Jharkhand through trade routes.

Over a period of time, the so-called lower classes got gradually absorbed within the folds of the agrarian setup. In fact, no agrarian economy in Bengal can really work without taking into consideration these autonomous people who were finally absorbed as labours (labour force in the fields)-to ultimately evolve into a proper serfdom. Though various scholars debate on the existence of a proper feudal feature in West Bengal, the medieval period of the state witnessed the growth and development of various autonomous local powers as well as different vassal chiefs under them. It is also interesting to note the close association of the local aristocracy, who often had vratya origin and shared a close-knit relationship with the locals under them. The significant effect of this association was the assimilation of ideas and beliefs, especially of the tribals, which permeated into the agricultural group similar to a symbiotic relationship and helped to win the confidence of the people.

Several of these rites, rituals and ceremonies were influenced by economic and financial activities of the region, including the agrarian cycle. Thus, the Radh region presents an interesting blend of an array of ceremonies, festivals, melas, rites and rituals, all of which have a folk or Brahmanical origin or an assimilated admixture where both categories of ceremonies exist within the same sociocultural and religious framework without a skirmish. These festivals further help us not only to understand the modern cultural scenario, but also to find traces of rites and rituals followed in the past in the region chosen for study. It is also significant to note here, the addition of the gradual process of social acceptance of certain Mangal Kavyas (folk epics centered on folk gods and goddesses written in Bengali), such as the Manasamangal Kavya, into the social setup. From 5th-7th century onwards, many domestic folk festivals of the region of West Bengal were elevated to the status of mainstream agrarian tradition and culture, as they gradually got acceptance in the mainstream Puranic traditional agrarian rites and rituals. One instance is seen in Manasamangal Kavya, which started getting recognition by the Puranas around this time onwards. Amidst these festivals, many pertain to the sowing season, the reaping of the harvest, paying oblations to one's ancesters, fertility rites, and rituals for overall security of the village. These offerings also include various articles and artifacts from the daily life, especially the ones witnessed in rural Bengal, including the rampant use of turmeric, betel leaves, bananas, coconut, cow dung, different alpana's, etc. To this list, various votive offering such as terracotta horses and elephants of various sizes and shapes may be included, especially in the region of study. Over a period of time, as these traditions from the so-called lower classes of the society got accepted within the folds of the agrarian so-called upper castes, the deities also made their way into an accepted orthodox tradition gradually. Thus, the culture of the adivasi vratyas eventually and evidently got acceptance into the mainstream Puranic-Brahmanical fold, with some of them getting changed slightly and others maintaining their true identity. This phenomenon is quite unique to the area of Mednipur, Purulia and Bankura, as in many other regions of the country, the folk and household traditions exist as a distinct category from the mainstream Puranic traditions.

Previous Work Pertaining to the Region

The work done so far pertaining to festivals and agriculture in India has been independent studies. There has been no attempt to sublime and amalgamate the thoughts of one discipline into the other, and expand the parameters for a more holistic study. Mostly previous works have been separate efforts to understand the systems of folk culture and traditions in the region or to understand the importance of the more popular and widely known agrarian festivals of the region, such as Durga Puja, Basantotsav, etc. The aspect of the inter-relationship of the Puranic-Brahmanic rites and rituals and the lesser known, yet widely followed, traditions was not taken into purview before to lead to an understanding of the importance of these festivals and the peculiar coexistence of different agrarian rites and rituals within the same social setup.

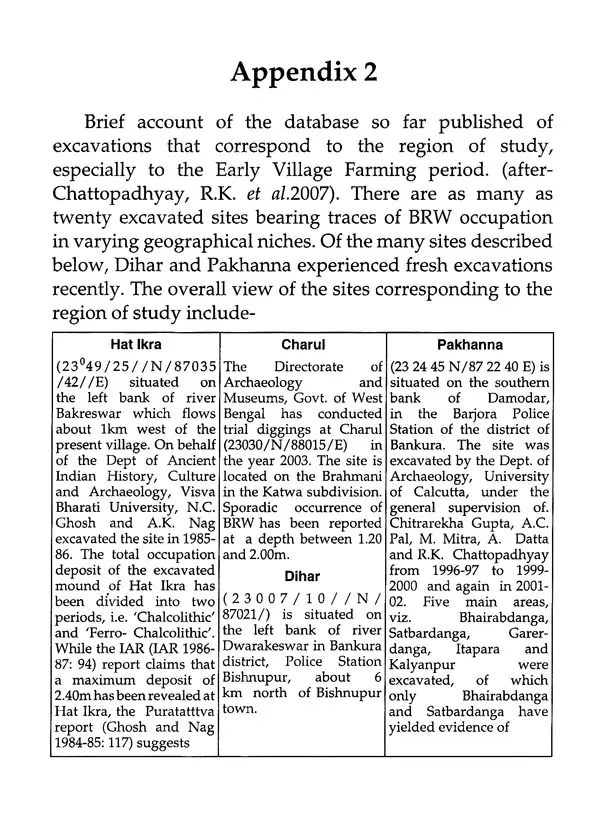

**Contents and Sample Pages**