The Indian Temple - Mirror of The World

Book Specification

| Item Code: | NAH707 |

| Author: | Bruno Dagens |

| Publisher: | INDIRA GANDHI NATIONAL CENTRE FOR ARTS |

| Language: | English |

| Edition: | 2016 |

| ISBN: | 9788178224855 |

| Pages: | 330 (47 B/W Illustrations) |

| Cover: | Hardcover |

| Other Details | 9.0 inch X 5.5 inch |

| Weight | 570 gm |

Book Description

Mirror of the world, the "Indian" temple mirrors India, by whom it has beer created, as well as the cosmos where live its gods. Through it, architects and sculptors inspired by theologians have known how to re-invent Space and Time. combining both of them in a continuous performance, where the Creation of the Universe starts over and over, again and again and is constantly repeated through daily ceremonies and solemn festivals. To ensure continuity in this performance they have petrified it in the temple ornamentation in the same way that the) have inscribed the cosmos and it! arrangement in the temple architecture a! well as the pantheon and its mythology in the images on its walls.

This Indian temple, like the church mosque, or even the Greek temple which it has sometimes encountered has spread all over the world, thereby following the doctrines which produced it. It has thus: become the mirror of many cultures, each of which has given its own interpretation in accordance with its own genius, but without ever discarding its bask characteristics which, as are defined if architecture treatises, allow recognition of its unity.

In ancient times, the temple blossomed in India and then went t< South>

This book aims at gathering in one presentation all these "Indian" temples, irrespective of their origin and their date. Attempting to delimit the mutual contribution of each concerned culture, it constantly draws a parallel between theoretical data and actual monuments, from the oldest to the more recent and through the liveliness of Indian traditions which they bespeak.

BRUNO DAGENS, Professor (Emer.), historian, archaeologist, and Sanskrit scholar from Paris III University has long sojourned in Asia, mainly in Cambodia and India, but also in Thailand, Laos, and Afghanistan where he has devote numerous years to the study of the temples which he has frequented, often daily in various locations.

IGNCA explores knowledge related to Indian Art and Culture in multiple dimensions and at different levels, through its various research programmes. These programmes are mainly carried out through five divisions known as Kala Nidhi (Library & Information Division); Kalakosa (Research and Publication Division) ;Janapada Sampada (Division for the Study of Diverse Living Traditions); Kala Darsana (Division for Exhibition and Presentation); and Sutradhara (Division for Administration and Co-ordination). It also has a well-developed Media Unit for audio-visual documentation and film-making, as also a Cultural Informatics Lab for the production of interactive multimedia CDs, DVDs and developing a National Digital Data Bank on Culture.

In Kalakosa Division the main focus is on research and publications, carried out through its three fundamental programmes. Kalatattvakosa is the first, representing the intellectual vision in a series of multiple volumes shedding a fresh light on Indian thought system and the categories of knowledge. The second programme is Kalamulasastra devoted to the publication of critical editions with translations of the fundamental texts which are basic to the Indian artistic traditions and also primary texts that are specific to a particular art. Kalasamalocana is the third programme which comprises publication of critical writings on different facets of art and aesthetics. This series concentrates on the works of eminent scholars who have dwelt upon fundamental concepts, identified perennial sources and created bridges of communication while placing diverse traditions side by side. The criterion for selecting these publications is the value of the works for their cross-cultural perception, multi-disciplinary approach and inaccessibility for reasons of language or being out of print.

In this light, the publication of this volume titled "The Indian Temple - Mirror of the World" is a welcome addition to our Kalasamalocana series. It is a manual on Indian temples that contains information related to the ideas behind the building of temples not only in India but also across the continent and, indeed, the globe. The Indian temple, representing the Universe, is an amalgam of consecrated time, space, elements and form. This has been analytically interpreted here according to Indian theology and as has been defined in the treatises on architecture. It also discusses the spread of the Indian temple all over the world, encountering various doctrines, especially in South-East Asia during ancient times and more recently on a much wider scale as a result of ever growing Indian Diaspora. In this way, Indian temples reflect the features of many other cultures while maintaining its basic characteristic that allowing the recognition of its unity.

We are grateful to Prof. Bruno Dagens for preparing the English version of his book which he had originally published in French and offering it to IGNCA for publication. Prof. Dagens has a long association with IGNCA. His critical edition along with its English translation of the well known treatise on architecture Mayamatam became a popular source book for both students and scholars working in the field of architecture and town planning, after its publication by IGNCA. I hope the present volume will receive an equally warm reception and we trust it will fulfill the quest of knowledge regarding the Indian temple not only of specialists but also of the common reader.

The title of the present volume, "The Indian Temple - Mirror of the World" carries a multidimensional meaning of the Indian idea or thought that has given form to the Indian temple. The author, Prof. Bruno Dagens also has elaborted on this in detail. At the same time, it may not be out of place to refer here to one of the towering figures of classical India, Acharya Abhinavagupta, whose millennium year we are presently celebrating. His ideas were studied all over the sub-continent. The range of disciplines that he mastered and the erudite commentaries that he authored have remained unparalleled through the ages. According to his concept, the world is not a material reality but a reality in consciousness. Abhasa and pratibimba are the two important terms, the meanings of which may be given as 'appearance' and 'reflection' respectively. The meaning may be elaborated further by an example: when we see our face in a mirror, the position of the actual face remains as the archetype (bimba) and what is reflected in the mirror is appearance or reflection. For more clarity, the term abhasa may be distinguished from the term vimarsa meaning "thinking", When one imagines one's face in one's mind, that can be termed as vimarsa Oust a thought), but when one sees the reflection in a mirror, it is abhasa, as it is an actual appearance. In this way, we see that abhasa (appearance) is objective but not material, as it is not a real object.

The world is abhasa projected or reflected in the mirror of cosmic consciousness. Abhinavagupta in the verses of his Tantraloka (TA) explains this position with one of his favourite analogies, the analogy of the reflection in a mirror:

Just as earth, water etc. are reflected in a clean mirror without being mixed, so also the entire world of objects appears together in the one lord consciousness. (TA 3.4)

The lord appropriates the entire world to himself (reflecting the world) in the mirror of his consciousness, and in this way he has pure ubiquity. (TA 3.44)

This entire world of many-ness appears in the self (consciousness) like a reflection (pratibimba) and the self is the lord of the entire reflected world. (TA 3.268)

But in the case of the world being reflected in Siva-consciousness, i.e. consciousness, as the Self or Siva is the bimba (the world) that is reflected and consciousness is also the mirror in which the world is reflected. This is unlike the passive mirror which receives reflections from outside, as consciousness actively creates its own reflections. Therefore, consciousness is a creative mirror that creates reflections from within itself. Thus, the real reflector is consciousness. This theory teaches how to be aware in daily activities like talking, walking, tasting, touching, hearing or smelling. By practicing this, every action of an individual moves in the supreme consciousness.

The Indian temple emerges as one of the remarkable expressions of this very thought process. Prof. Degens has drawn on the tradition texts and treatises on architecture while divulging the idea behind the creation of the temple. His analysis of the origin of the temple followed by its spread all over india and around the globe is remarkable.

The Indian temple and the concepts related to it have been discussed in IG CA's diverse programmes. For instance, in our series of key concepts, viz. Kalatattvakosa, the term prasada appears in the Volume Von Form/Shape: Akara/ Akrti. Amongst many other meanings, the term prasada stands for both 'temple' and 'palace'. The term also represents Cosmic Purusa, the Cosmic Tree and the axis mundi. Prasada enshrines mantra, tantra, yoga and jnana and is visualised not only as an abode of godhood, but as the manifestation of God. In the ultimate analysis, prasada is identical with supreme knowledge. The terms murti, pratima and vigraha from the same volume enshrine in them further minute details related to the Indian temple. Under the programme of Fundamental Texts - the Kalamulasastra series - three texts related to temple have been published, viz. Mayamatam, Silpa Prakdsa and Silpa Ratnakosa: These have become source materials for the specialists working in the field of architecture.

In order to analyse the Indian temple in all its dimensions, viz. conceptual, literary, textual, historical, epigraphical, crafts traditions, ritual calendars, ritual treatises and performances, IGNCA also initiated two multidisciplinary projects, one in the South - the Brhadisvara temple in Tanjavur and the other in the North - the Govindadeva temple at Vrindavana. Several publications have been published under these projects. Recently in 2014, IG CA released an interactive multimedia DVD on the Brhadisvara temple as a living tradition.

In the Kalasamalocana series, IGNCA has brought out a number of publications dealing with temple architecture. What is most important here is to note that through the initiative of IGNCA a new line of scholars has emerged in whose studies a shift of emphasis and change of perspective on the study of the temple as an all encompassing entity is observed.

The inception of the present volume goes back to the year 2012 while meeting Prof. Bruno Dagens during the 15th World Sanskrit Conference held in New Delhi in January that year. Although Prof. Dagens' scholarship was known much earlier, especially since his monumental work on a seminal treatise on architecture, viz. Mayamatam was published by IGNCA in 1997, my first personal acquaintance with him took place at Helsinki, Finland in 2003. During the 11th World Sanskrit Conference held there, Prof. Dagens had chaired the first session in the Tantra-Agama section and I had presented my paper on a tantra practiced in Kashmir.

During our discussion at the Delhi Conference, Prof. Dagens informed about his plans of preparing the English translation of his book on the Indian temple which had already been published in French. He also wanted to know if lGNCA would be interested in taking up that for publication. This was how it started. Thereafter, I worked out the modalities for taking it up as a publication project. It was fitting well into our Kalasamalocana series focussing on analysis of arts. In due course Prof. Dagens submitted his translation and our work started in respect of making it worthy of publication and completing other necessary formalities. It is now heartening and deeply satisfying to see our efforts fructifying in presenting Prof. Bruno Dagens' work as a published volume under one of our prestigious publication series.

Contents

| Foreword | vii |

| Preface | ix |

| Introduction | 1 |

| (Insert: Architectural Treatises) | 2 |

| | |

| Chapter I: The God at Home | 13 |

| The God | 14 |

| The Cult Object (p.14); In the Image of Man (p.17); From Object to God: Installation and Worship (p.18) | |

| Officiating Priest and Devotees | 19 |

| "Minimal Project" for a Temple | 21 |

| A Basic Dwelling Unit (p. 21); Universality of the project (p. 23). | |

| From Sanctum to Temple and from Temple to Sanctuary | 24 |

| Temples without Architecture and Hypaethral Temples | 25 |

| Chapter II: From the Sanctum to the Temple | 29 |

| The Sanctum | 29 |

| Basic Functional layout (p. 29); (Insert: Sanctum with a Double Function) (p. 30) | |

| Obvious Constraints | 31 |

| Interior Volume Delimitation | 32 |

| Walls, Partitions, and Materials (p. 32); Covering the Sanctum (p. 34) | |

| Plan of the Sanctum | 37 |

| En trance to the Sanctum | 39 |

| Door and Doors (p. 39); Door(s) and false-doors (p. 41) | |

| Orientation | 43 |

| Inner Arrangement of the Sanctum | 47 |

| Pedestal and Placing the Main God (p. 48); Draining away Bathing Liquids (p. 48); Bringing inside Bathing Liquids (p. 50) | |

| Turning Around the God in the Sanctum? | 51 |

| Encasing the Sanctum | 52 |

| Prototype and Developments (p. 52); Three Categories of Temple Developments (p. 53); Initial Project and History (p. 55) | 58 |

| Chapter Ill: The God's House | 58 |

| Prolegomena | 58 |

| Constraints | 58 |

| The orm | 60 |

| Theorizing the Facades (p. 60); Norm and Structure: From "Attic" to Superstructure (p. 63) | |

| Two Main Decorative Options | 65 |

| False Reversion to a Wooden Architecture? (p. 65); Geographical Distribution of the Two Options (p. 66) | |

| Perspective and other Effects | 67 |

| Colouring the Temple | 69 |

| Ground Floor Arrangement | 70 |

| Foreparts | 70 |

| Entrance Foreparts (p. 71); Chapel- or Pseudo-Chapel Foreparts (p. 73) | |

| Outwork Ambulatory and other Outwork Features | 74 |

| Temple Roofing | 75 |

| Generalities (p. 75); (Insert: Flat Roof Temples) (p. 77)); Horizontal Layout of Roofing (p. 78); Roof and Finial (p. 78); Attic and Summit Aedicule (p. 80) | |

| Superstructure: General Features | 81 |

| (Insert: Aedicules and "Pieces d'accent" (p. 83)); (False-) Storey | |

| Superstructure (p. 84); Stepped Superstructure (p. 88) | |

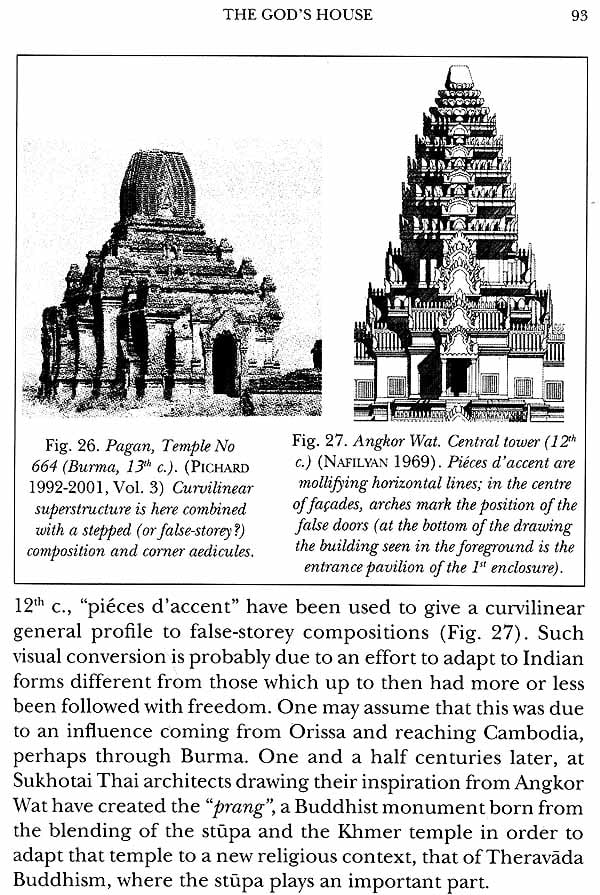

| Curvilinear Superstructure: Main Features and Geographical Distribution | 90 |

| Curvilinear Superstructure: Structure and Organisation 94 (Insert: Analysis oJ Curvilinear Superstructures) (p. 94). | |

| Superstructures: Facades and Technique | 97 |

| From a Simple Building to a Complex One | 98 |

| Pavilions | 99 |

| A Complement to the Sanctum | 100 |

| Form and Variations | 101 |

| Conclusion | 104 |

| Chapter IV: Sanctuary and Temple Precincts | 105 |

| Definitions | 106 |

| A Sacred and Delimited Space (p. 106); Variations of Enclosure (p. 106); "Density" of the Sacred (p. 108) | |

| A Beyond-the-Walls Space which is a "Necessary" One .. 109 | |

| A Wide Space Theoretically Unlimited | 110 |

| Theoretical Data: Practical Realities | 111 |

| The Space where a Temple-to-be will be Built | 112 |

| Factors to be Taken into Account Jor Choosing a Site (p. 112); Inside or Outside the City (p.1l3); Definition and Delimitation (p. 115 ) | |

| The Sanctuary, a Space Born from the Temple | 117 |

| A Limited, Measurable, and Measured Space (p. 117) (Insert: Temple Moat) (p. 118)); An Occupied and Inhabited Space (p.120) | |

| From Theology to Architecture through the Concentric | |

| Setting of Sanctuary | 122 |

| Archaeological Evidence (p. 122); (Insert: Mountain-like Temples and Concentric Enclosures in Cambodia) (p.125)); Theorising the Concentric Pattern (p.127); Entrance (p.129); Galleries and Similar Structures (p.131); What for a Pavilions Concentric Pattern? (p. 132); Beyond the Border oJ the Sanctuary (p. 134) | |

| Tiruvannamalai : Temple and the City | 135 |

| A Bipolar Holy Place (p. 135); Temple, Sanctuary and the City (p. 137); The Mountain (p. 140); By Way of Conclusion (p. 141) | |

| Angkor-Wat: Temple, City and State | 141 |

| Sanctuary Setting (p. 143); space Setting (p. 146); Changes in the space Organisation once the Temple Shifted to Buddhism (p. 148) | |

| Conclusion | 149 |

| | |

| Chapter V: Temple, Mirror of God | 153 |

| The Ritual Construction of the Temple | 154 |

| From Temple to God | 158 |

| Prolegomena (p. 158) | |

| Architecture as an Instrument of Definition | 159 |

| The Plan as a Signifying Element (p. 160); The Suggested Pantheon (p. 161); The Figured God (p.163); Perspective Effects and Religious Persuasion (p.167); Architecture and Persuasion (p.168) | |

| Iconography and Definition of the Temple | 170 |

| Images on the Temple and on its Annexes (p.170); Iconography and Iconographical Programme (p. 172) | |

| Organising the Sanctuary | 175 |

| The Sanctuary as a Projection of the Temple (p. 175); Bordering God's Estate (p. 177); The Pictured Temple (p. 178); Entrance Pavilions and Temple Enrichment (p. 180 ) | |

| Conclusion | 180 |

| Chapter VI: Temple, The Mirror of Man | 182 |

| Introduction | 182 |

| Temple and Human Hierarchies | 183 |

| The Right to Enter Temples: Social Hierarchy and Religious Law (p. 183) | |

| Social Hierarchy, Temple Hierarchy and Gods Hierarchy | 187 |

| The Festival or the Temple as a Unifying Centre? | 188 |

| The Temple and the King | 192 |

| A Preference Relationship (p. 193); Temple and the Rightful King (p. 195) | |

| State Temples | 196 |

| Tentative Infinitum (p. 196); State Temples and Architecture: General Features (p. 198) State Temples and Iconography (p. 199); State Temples and Symbolism (p. 201); Fate of | |

| State Temples) (p. 202); Kings' Disappearance and Change to a Secular State (p. 204) | |

| Conclusion | 205 |

| Chapter VII: Temple as a Performance | 206 |

| Introduction | 206 |

| Space and time (p. 206). | |

| Spectators and Actors | 207 |

| An Art of the Temple | 209 |

| A Necessary Beauty (p. 209); From Worship to Door Artistic Arrangement (p. 210) | |

| Animals in the Temple | 213 |

| Shade and Light upon the Temple | 216 |

| Water-plays and Mise en Abyme | 219 |

| Temple and Space: An Image of the Universe | 223 |

| Reaching the border (p. 223) | |

| Rites of passage | 224 |

| (Insert: The Dust upon Pilgrims' Feet) (p. 226) | |

| An Infinite or Quasi-Infinite Universe | 226 |

| Human Kingdom and Divine One | 228 |

| Performance and Time | 229 |

| Petrified Festival or Interrupted Time | 230 |

| Plants, from Daily Rites to Festival (p. 230); Petrified Plants, Makara, and Curtain (p. 231); Festive Elephants and Chariots (p. 232) | |

| Temple as Time-keeper | 234 |

| About the Value of Architectural Testimony (p. 234); A Dynamic Testimony (p. 236); Temple and Epigraphy (p. 236); Troubled Times (p. 237) | |

| Chapter VIII : Temple's Travels or the Indian Temple | |

| Throughout the World | 239 |

| Introduction | 239 |

| Prolegomena | 241 |

| Temple's Continuity (p. 242); | |

| Buddhism and Temple | 242 |

| Temple Travels throughout India | 244 |

| Regional Exchanges (p. 245); Adaptation to Environment (p.246) | |

| Travels outside India and Vectors' Problem | 248 |

| What Could Become Indian Temple in South East Asia (p. 248); Travelling Architects or Travelling Treatises (p. 250) | |

| Imaginary Travels and the Like | 255 |

| Archaeological Fantasies (p. 255); Gustave Moreau and the Eyes of the God (p. 256) | |

| Dream and Politics | 258 |

| Conclusion: | 259 |

| Indian Temple's Discovery | 259 |

| From Philostratus to Nikitin | 259 |

| Missionaries and Architects | 260 |

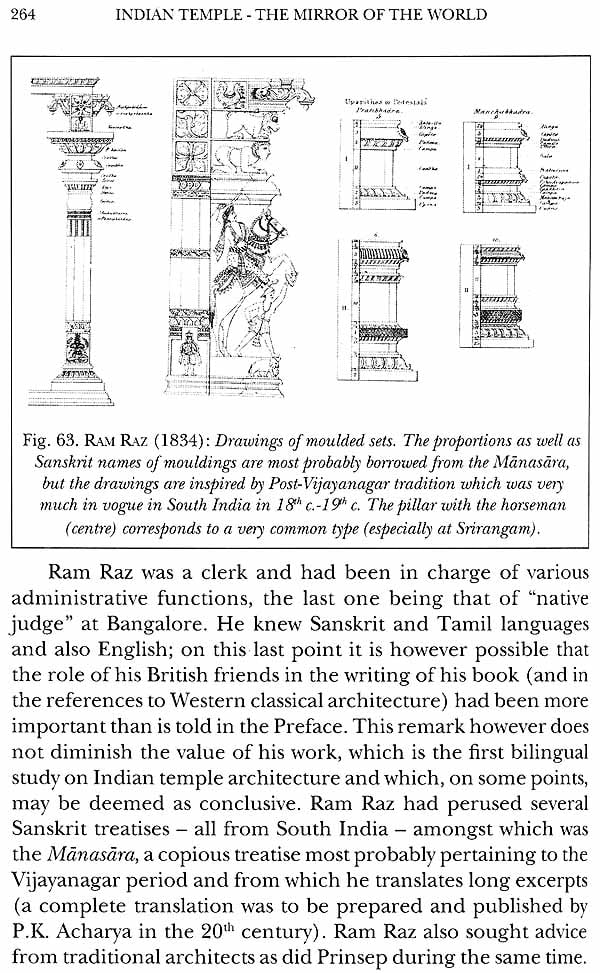

| Ram Raz, Towards a Bridge between Architectures | 263 |

| Towards a Global Study | 265 |

| New Temples | 267 |

| Social Minded Views and Projects for Safeguarding the faith | 268 |

| Expected Success ofa Hanuman Temple | 269 |

| The etworked Goddess Temple | 272 |

| Back to the Mirror | 275 |

| Glossary of Main Architectural Expressions | 278 |

| Bibliography | 284 |

| Topographical and Geographical Index | 293 |

| General Index | 299 |