An Island of Sal

Book Specification

| Item Code: | NAT102 |

| Author: | Shaani |

| Publisher: | National Publishing House |

| Language: | ENGLISH |

| Edition: | 1981 |

| Pages: | 88 |

| Cover: | HARDCOVER |

| Other Details | 9.00 X 6.00 inch |

| Weight | 290 gm |

Book Description

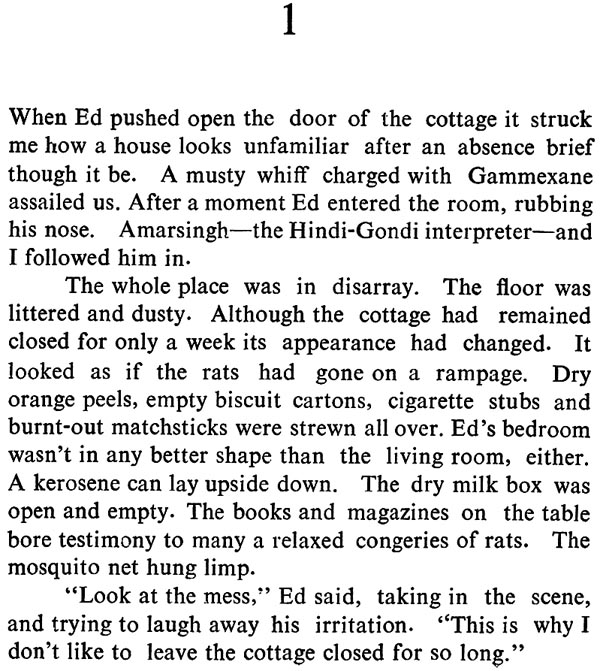

An Island of Sal is a factual account in fictional style of the social life of the tribesmen of Orcha, a small village in the Abujhmar Hills in Bastar. The Abujh (Hill) Maria Gonds, who are the aboriginals of the place, have been much romanticised elsewhere, if not ignored. Besides trying to portray the tribal as a man, the book also focuses upon relevant aspects of a study of the community conducted by an American social-anthropologist Edward J. Jay, and takes an unsparing look at the reactions of the author him- self, who is a renowned Hindi Novelist and short-story writer.

A lopsided assumption is rife with respect to all backward tribes, particularly those of Bastar, that they are a happy lot, that their life brims over with joy and resounds with songs and untiring rhythm of dance. But there is a parallel picture, too—a picture which may be suppressed by the former one because of Its strident sentimentality but which nevertheless shows what is undoubtedly their more realistic profile.

An Island of Sal is a factual account in fictional style of the social life of the tribesmen of Orcha, a small village in the Abujhmar Hills in Bastar. The Abujh (Hill) Maria Gonds, who are the aboriginals of the place, have been much romanticised elsewhere, if not ignored. Besides trying to portray the tribal as a man, the book also focuses upon relevant aspects of a study of the community conducted by an American social-anthropologist Edward J. Jay, and takes an unsparing look at the reactions of the author him- self, who is a renowned Hindi Novelist and short-story writer.

A lopsided assumption is rife with respect to all backward tribes, particularly those of Bastar, that they are a happy lot, that their life brims over with joy and resounds with songs and untiring rhythm of dance. But there is a parallel picture, too—a picture which may be suppressed by the former one because of Its strident sentimentality but which nevertheless shows what is undoubtedly their more realistic profile.

It is a pleasure and an honor to write this foreword on behalf of my friend and companion, Shaani. His generous assistance during my stay in Bastar made the social anthropological study of the Hill Maria Gonds possible, and contributed substantially to its success.

Any account of those days among the Hill Maria Gonds fills me with nostalgia and pleasant memories. For eighteen months my ex-wife and I lived in the village of Orcha, at the base of the Abujhmar Hills, an idyllic setting in one of the still sparsely populated regions of India. The quiet people of Orcha cling valiantly to a traditional and highly valued way of life in the midst of a changing world.

The Maria Gond homeland is a place of hills, forests, and streams. Along the banks of a nearby river which the people of Orcha have named after their own village, one can find rice fields worked with bullock-drawn plows. But the Gonds, or Koitur as they call themselves, refuse to abandon completely their ancient slash-and-burn cultivation on the hilly slopes to the west of the village. Here are grown millets, pulses, beans, squashes, potatoes, and other vegetables by the simple process of cutting, burning, clearing, and sowing. The only tools used are the axe and the hoe.

But the forested hills are more than just a site for cultivation. They are the source of many useful household products, such as leaves for leaf-cups, and bamboo for baskets. The forests are rich with wildlife as well, and occasionally a deer, hare, or jungle fowl is shot with bow and arrow, adding variety to the diet.

Out of the hills run rapid streams which are blocked by makeshift dams during the rainy months, so that the water spills out over the cultivated fields below. Basket- shaped fish weirs are also placed in the streams at this time, and fish are caught in abundance.

The people of Orcha look to the hills for still other reasons. There dwell the rest of the Koitur, in numerous tiny settlements which shift their location from time to time to allow the exhausted land to rejuvenate. From these small villages the men of Orcha receive their brides, and send their sisters in return. Thus a network of kin- ship is established, which links Koitur throughout the Abujhmar region. On festival occasions such as kaksar in the Spring, the Koitur youth assemble first at one village then at another to observe the religious rites, to dance, drink, and make merry in the evening. Out of these celebrations liaisons between boys and girls of different villages develop, and these often form the basis of marriage.

The Koitur are a happy people, and life among them was a pleasant experience. In the early morning and late afternoon I would join the men of the village at a sago palm tree in the nearby forest for a refreshing drink of effervescent palm wine. Here we would sit in a circle, with a fire in the center, drinking from our leaf-cups, enjoying the beverage and the company of our fellow men. News and gossip of the village were exchanged, and in the morning the day’s plans were made. If a ceremony was soon to be held, the men had to make sure everything was ready. Everyone had to provide the pigs, chickens, and grain which the gods would demand in sacrifice and which the people would consume if the gods were pleased. A special/eské, or shaman, might have to be called from a neighboring village, and the men had to decide who would summon him.

Orcha itself has three resident shamans, and they are renowned for their performances. The people believe that these men have the power to get the deities into their bodies, and by this means people can communicate directly with the gods. The ceremonies are exciting, the leskés sometimes doing a wild, uninhibited dance to the beat of drums, after which they settle down and converse in the excited, quivering voice characteristic of the gods. They admonish the people to do their duty to take care of their fields, and to perform the sacrifices.

An Island of Sal is not a novel, nor is it a travelogue; it is a factual narrative of the social life of the tribesmen of Orcha, a small village in the Abujhmar in the backwoods Of Bastar—-a district of Madhya Pradesh. Through it, I have endeavoured to acquaint myself with the pain and pleasure of the Maria Gonds—the aboriginals of the place—smothered as they are under the rubble of customs and traditions, social mores, and religious beliefs and superstitions.

I have little to do with either sociology or anthropology. First and foremost I am a writer; itis a work I like. Perhaps I should have written a novel on the life of these tribals. I had, indeed, wanted to do so but later I decided in favour of the present form. The novel has its limitations, or at least so it appears to me, when the aim is an objective but meaningful exposition of the way of life of the tribals in its entirety, their problems and para- doxes. This difficulty will be faced by any honest writer brought up in a city with its different culture. To this day, I have not been able to understand how a novel can be written on alife of the undercurrents of which you have no inside experience; such an effort is bound to result in nothing more substantial than a mere reportage. Perhaps an honest novel on these people will be written when someone from amongst themselves rises to the task; only such a writer will be able to give shape to their true feelings and sensibility.

A lopsided assumption is rife with respect to al) backward tribes, particularly those of Bastar, that they are a happy lot, that their life brims over with joy and resounds with song and untiring rhythm of dance. Strange that my contact with them should reveal another parallel picture —a picture which may be suppressed by the former one because of its strident sentimentality but which neverthe- less shows what [ think is their more realistic profile. I have always wondered if a people can be summed up within the confines of but a few customs, songs and images evocative of a quaint sense of values.

Anyway, this is a narrative about Orcha, and the charac- ters in it are drawn from Orcha. The tribulations, the problems, the paradoxes, either explicit or implicit in this narrative, are an authentic reproduction of the way of life of these tribals. But are these true of Orcha alone ? Isn’t the whole of the Abujhmar grappling with all these and maybe tenfold greater difiiculties? And isn’t all this happening to the tribesman not only in Bastar but else- where also?

**Contents and Sample Pages**