Smita Patil (A Brief Incandescence)

Book Specification

| Item Code: | NAL193 |

| Author: | Maithili Rao |

| Publisher: | Harper Collins Publishers |

| Language: | English |

| Edition: | 2015 |

| ISBN: | 9789351775126 |

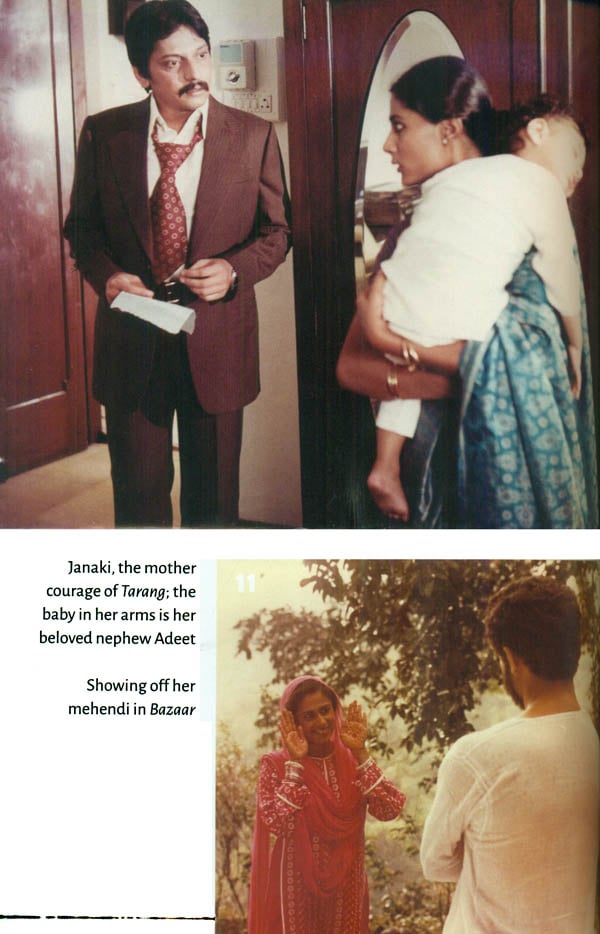

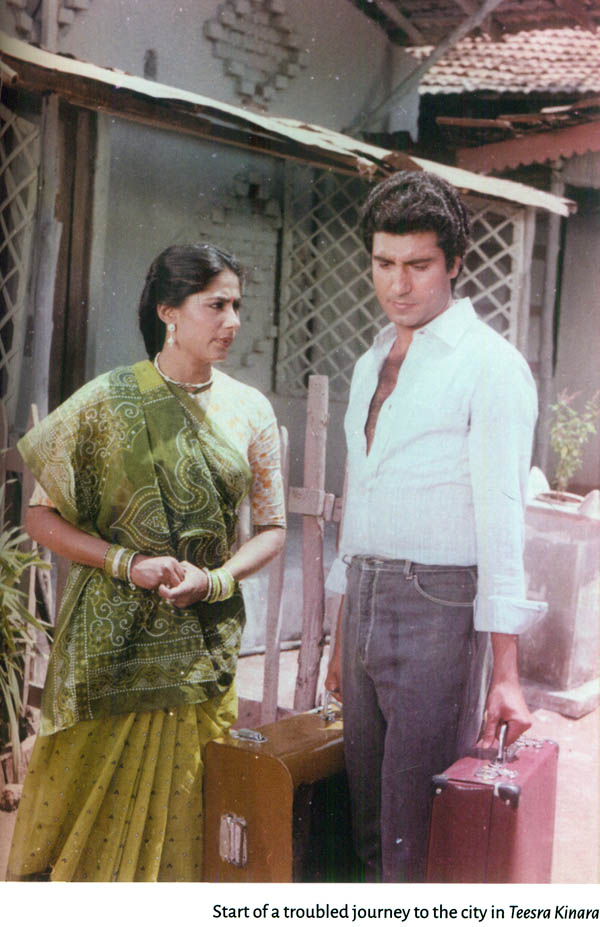

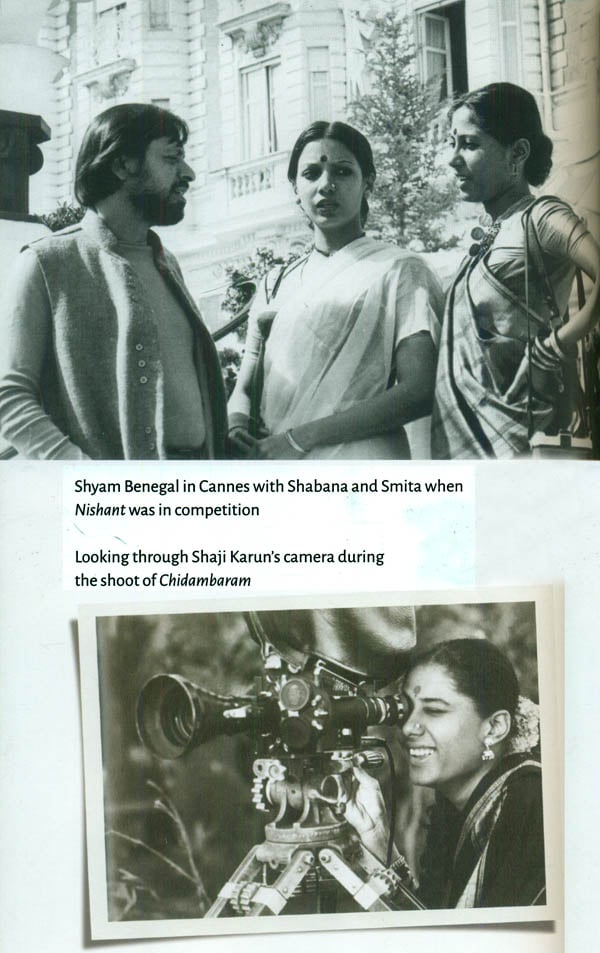

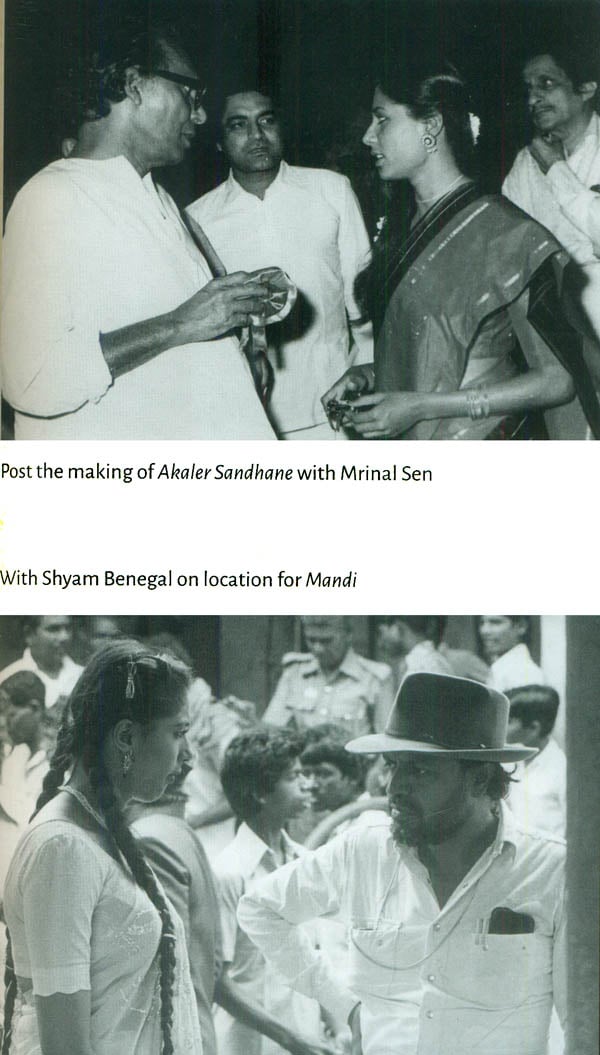

| Pages: | 384, (16 B/W and 9 Color Illustrations) |

| Cover: | Paperback |

| Other Details | 8.5 inch x 5.5 inch |

| Weight | 340 gm |

Book Description

In the three decades since Smita Patil died –at the impossibly young age of thirty—one –she has become one of India cinema’s biggest icons.

Smita Patil: A Brief Incandescence tells her remarkable story, tracing it from her childhood to stardom, her controversial marriage and untimely death. Her close friends remember ‘Smi’ as outspoken and bindaas, not beyond hurling abuses or taking off on bikes for impromptu joyrides. Film-makers Shyam Benegal and Jabbar Patel and co-stars Om Puri and Shabana Azmi talk about Patil’s dedication to her craft and her intuitive pursuit of that perfect take. From the difficult equation she shared with her mother to her propensity for ‘wrong’ relationships, about which she was always open unlike other stars of the time, this is a complex and honest exploration of Patil’s life. It includes a critique of the films that defined her and read like a roster of the best of New Indian Cinema: Bhumika, Mandi, Manthan, Umbartha, Bhavni Bhavai, Akaler Sandhane, Chakra, Chidambaram and Mirch Masala among others. The author also examines Patil’s many unfortunate forays into mainstream commercial cinema.

Incisive and insightful, this is the biography of a rare talent.

Maithili Rao is an ex-English lecturer who drifted into film criticism through happenstance. She has written extensively for Indian and international publications. Currently a columnist for Man’s World, she has written regularly for The Hindu, Frontline, Cinema In India, Film Comment, International Film Guide, BFI website, South Asian Cinema, Gentlemen, Eve’s Weekly (a long-running monthly column, ‘Images of Women’), The Sunday Observer and Independent (foreign film critic for the last two).

She has served as member of the jury for National Awards and critics’ jury at international film festivals (Sochi, MIFF-Mumbai, International children’s film festival-Hyderabad, Bengaluru International film festival). She also served as nominations council member of the Asia Pacific Screen Awards, Australia. She has contributed chapters to books on Indian cinema: ‘Rebels without a Cause’ for the Encyclopaedia Britannica India volume on Hindi cinema; ‘Heart of the Hindi film’ for Bollywood, Dakini Publications, London; “To Be a Woman’ for Frames of Mind, Indian Council for cultural Relations; ‘Images of Women’ for Rasa, Vol. II, edited by Anil Dharker, Roli; ‘Idealized Women and a Realist’s Eye’ for Bimal Roy : The Man Who Spoke in Pictures, edited by Rinki Bhattacharya, essays for Madhumati and Janani by Rinki Bhattacharya.

She lives in Bombay with a forbearing husband who is not interested in films but calmly survives her deadlines and film mania. An allied activity has been subtitling films from Hindi, Telugu and Kannada into English.

Smita was the proverbial girl next door. You hardly noticed her. She could easily get lost in a group of young people and become quite simply an anonymous presence.

She was dark complexioned, in a profession that worships fair-skinned women. None of the stereotypical definitions of feminine beauty prevalent in the Indian film industry could define her. It was when she faced the camera that she was transformed into an irresistible magnetic presence that every actor strives hard for, but rarely if even manages to achieve to the extent she did.

In her short career that spanned all of twelve years, Smita Patil’s incredibly riveting and memorable performances in practically all the films she acted in, have remained the envy of most actors in Indian cinema. Anyone who knew Smita as an acquaintance, a friend or a professional colleague remembers her as a guileless, spontaneous young woman given to great enthusiasm.

She had an incredibly wide range of interests, to the extent that her film directors (I speak from experience) would constantly worry that these would come in the way and distract her from the role she was playing in the film she was doing at the time. This never happened because she had that rare ability to switch on and off at will. The moment the stepped in front of the camera lens, she was totally focused. Equally and exasperatingly, she could be completely divorced from the film the moment she moved away from the film set. Smita was not a trained actor. Instinct and intuitiveness played an extremely important part in her performance. Perhaps, this was the single most important reason that made her performances irresistibly attractive and credible.

Maithili Rao’s well-researched book is an extremely perceptive introduction to Smita’s life and her exceptional work as an actor in Indian cinema.

She was Indian cinema’s Everywomen. Her genius shone through in rendering the everywoman extraordinaire with a signature hypnotic allure, a depth charged with intensity that exploded into emotions on celluloid, grand and subtle, dramatic and nuanced all at once. What is the key to unlocking Smita Patil’s haunting presence on the silver screen? Is it her finely sculpted face that can be so expressively mobile? Or those wide and deeply set eyes-when they accuse, you feel a twinge of uneasy guilt; when they are mute with agony, you suffer with her. What about that wilful and generous mouth full of passion-love and hate, rage and the promise of husky laughter? A voice vibrating with emotion, seemingly capable of infinite inflections, sometimes surprising you with girlish trills of gaiety. Her silence spoke as eloquently as her full-bodied voice, setting off tremors of complexities. The least flamboyant of gestures and the suggestion of a half-smile expressed a range of meanings. With the proud carriage of a born fighter, valiant as she is vulnerable, Smita created a new grammar of intensity and complexity. She subsumed her self and mannerisms to the demands of the role. Her body had the tensile strength of steel balanced with the suppleness of a reed. These are marvellous assets and a good actor is one who uses these inherent gifts wisely to bring out the familiarity of common experience, and yet portray the particular idiosyncrasies of the screen character.

Smita’s face fascinates; she has an earthy Indian look that could belong to any part of India. So many of her brilliant portrayals come to mind: a fiery Gujarati Dalit (Manthan), a free-spirited gypsy (Bhavni Bhavai), the migrant Bihari peasant who transforms from nurturing earth mother into avenging Kali (Debshishu), the vivacious Tamil wife ripe for extramarital amour in lush Kerala highlands (Chidambaram), an older widow navigating the crime and grime of a Bombay slum, coping with her young son’s drug habit even as she unravels her own love life (Chakra), a genteel housewife of Calcutta (a gem of a performance in Abhinetri, in the TV series Satyajit Ray Presents....), the Deccani Muslim woman who sells a young impoverished bride to an older Gulf-based man to cement her own uncertain status with a lover who will not commit to marriage (Bazaar), the uninhibited tribal woman giving her all to the love of her life (Jait Re Jait), a Maharashtrian upper-class woman with a conscience, who finally finds her vocation (Umbartha), the lonely writer wrenched from her daughter (Aakhir Kyon) and the traditional wife caught in marital misunderstanding (Bheegi Palkein). All these roles, albeit not as famous as her work in the more celebrated Bhumika and Tarang, depict a vibrant inner life apart from the external portrayal, convincing body language and bearing that bring the on-screen character alive.

Mrinal Sen endorses this unique talent to be everywoman. ‘Smita’s is an eventful story built in an incredibly short span of time, walking from one film to another, growing from strength to strength. Her versatility is a delicious feat, her range beyond easy measure. Her versatility is a delicious feat, her range beyond easy measure. And true, she always makes herself spectacular by her natural qualities, by remaining exceptionally ordinary [the emphasis is mine], by her elegance and poise, and topping it all, by the intensity which surfaces irresistibly from within.’ Sen goes on, ‘India is a country where people speak diverse languages, wear different outfits and where the people are easily identifiable by their different physiognomies. But pull Smita out from anywhere and throw her into any milieu in any part of the country and, surprisingly, she looks deeply rooted in it’.

Of course she made inexplicable choices in her personal life and career, something that confounded and disappointed her fans. That makes her human, not a devi to be put on a pedestal. Vulnerability is essential for a person to experience a range of emotions and even more so for an actor; it enables her to convey the tumult of the screen woman she portrays. Career choices need to be examined in their context and the personal must be respected—especially when she is not here to defend herself.

A veteran journalist, now based abroad, asked me amid the chatter of many simultaneous conversations endemic to a film festival: ‘Do you think she deserves a book?’ This book is my answer. Smita Patil is a living memory to many of us. Her contribution to Indian cinema, in redefining the Indian woman and interpreting her complexity in memorable films, is immense.

17 October 2014, Nehru Centre auditorium, Worli, Mumbai: Jhelum Paranjape’s students from Smitalay, the Odissi school run by this childhood friend of Smita, perform an innovative ballet Leelavati. With a cast of over a hundred dancers, the ballet asks and solves mathematical problems using Sanskrit shlokas, with imaginative choreography and inventive storytelling. In the audience are Shivajirao Patil and Dr Anita Patil-Deshmukh, Smita’s \father and older sister. On the stage is a black-and-white portrait of Smita placed beside a brass diya. After the rousing performance, in an atmosphere of loving remembrance, Jhelum invites Prateik to the stage.

Overwhelmed by emotion even after all these years, Prateik goes up and sings ‘Happy birthday angel’, echoing the emotion that pulses gently through the crowd. Time has blunted the edge of grief but not our mourning; our poignant memories of her excellence linger in the air that envelops us. It is almost palpable, the mesmerizing memory of her, the warmth in our hearts.

Such abiding emotions, such collective memory, are not created in a vacuum. Smita was born in the dawn of our new cinema and grew to maturity in that creatively rich milieu. Destiny brings the right people together at the right time in history. What eminent critic James Monaco wrote of the French New Wave in 1979 is as true of the Indian New Wave: ‘ The metaphor of the “New Wave” was surprisingly apt: the wave had been building up for a long time before it burst on cinematic shores.’

The 1970s were a time when the calcified mould of mainstream cinema began to break up, and amidst its splinters, shoots of vibrant, personal perceptions of film aesthetics struggled to find audience acceptance. All through the post-Emergency years when the Angry Young Man ruled the screen, there was a sense of fatigue with the formula building up. There was slickness of narrative and smart technology-aided gloss, but the themes were confined within narrow limits. Melodrama and romance, vengeance and violence were the bricks that built the box office pyramid. The reality of Indian life, its endless struggles, challenges and frustrations, little joys and great sorrows, the sheer variety of a multi- cultural pluralistic society were not being portrayed, neither by mainstream Mughals nor by slavish followers of a successful new formula.

Satyajit Ray, Ritwik Ghatak and Mrinal Sen had shown that a different kind of cinema was possible. A cinema of personal vision that came from deep within a cultivated sensibility and educated intellect. One that was alive to the ferment at home and yet open to the winds of change wafting in from the world outside. Bengal acted like a beacon—as it had so many times in the past—to film makers in other regions who forged a cinema that was rooted in their ethnicity and culture. It was a reassertion of the authentically local against the conformism demanded by mainstream cinema, not just Hindi but its regional counterparts too.

Auteurs of the new cinema flourished when the government stepped in-the Film Finance Corporation offered funding to a host of film makers—many were often anti-establishment, a few espoused avant garde experimentation, most were neo-realists who wanted to tell the truth without the embellishment of song and dance that is so inherent to our narrative traditions, and a minority of adherents pursued purist non-linear cinema. Wavelets of change were acting cumulatively to build up the surge that changed our cinema in the 1970s, through to the 1980s, until is petered out as any unstructured movement does in the course of time. New Cinema as a movement ran out of steam. Auteurs remained, ploughing their lonely way with admirable conviction even though they could not build up an alternate distribution system. Only the film festival circuit and Doordarshan were available. It is interesting to speculate whether parallel cinema could have thrived if multiplexes had arrived in the 1980s and catered to what was always a niche audience.

| Foreword | ix | |

| Introduction | xi | |

| 1 | Anchored to Her Puneri Roots | 1 |

| 2 | Reluctant Move to Beckoning Bombay | 21 |

| 3 | The Seminal Seventies | 35 |

| 4 | Smita Patil and Her Dasavatars | 66 |

| 5 | Ensemble Excellence | 161 |

| 6 | The Ambivalent Eighties | 192 |

| 7 | The Woman Behind the Image | 257 |

| 8 | The Way We Remember Her | 292 |

| Afterword | 320 | |

| Filmography | 323 | |

| Index | 337 | |

| Acknowledgements | 345 |