Why I Killed the Mahatma (Uncovering Godse's Defence)

Book Specification

| Item Code: | NAN395 |

| Author: | Koenraad Elst |

| Publisher: | Rupa Publication Pvt. Ltd. |

| Language: | English |

| Edition: | 2018 |

| ISBN: | 9788129149978 |

| Pages: | 269 |

| Cover: | Hardcover |

| Other Details | 8.5 inch X 5.5 inch |

| Weight | 400 gm |

Book Description

Back of the Book

‘It is a fact that in the presence of a crowd numbering 300 to 400 people I did fire shots at Gandhiji in open daylight. I did not make any attempt to run away; in fact, I did not try to shoot myself; it was never my intention to do so, for it was my ardent desire to give vent to my thoughts in an open Court.

About the Book

It is common knowledge that Mahatma Gandhi was shot dead in 1948 by a Hindu militant, shortly after India had both gained her independence and lost nearly a quarter of her territory to the new state of Pakistan. Less well-known is the assassin Nathuram Godse’s motive. Until now, no publication has dealt with this question, except for the naked text of Godse’s own defence speech during his trial. It didn’t save him from the hangman, but still contains substantive arguments against the facile glorification of the Mahatma.

Dr Koenraad Elst compares Godse’s case against Gandhi with critisms voiced in wider circles, and with historical data known at the time or brought to light since. While the Mahatma was extolled by the Hindu Masses, political leaders of divergent persuasions, who had had dealings with him, were less enthusiastic. Their sobering views would have become the received wisdom about Gandhi if he hadn’t been martyred. The author also presents some new considerations in Gandhi’s deference from unexpected quarters.

Dr. Koenraad Elst (Born in Leuven, Belguim in 1959), obtained MA degrees in Sinology, Indology and Philosophy, and a Doctorate in Oriental Studies with a dissertation of Hindu Nationalism. While intermittently employed in political journalism and as foreign policy adviser in the Belgain Senate, his scholarly research findings earned him both laurels and ostracism. His numerous publications concern Asian philosophies, language policy, democracy, Indo-European origins, Vedic history.

Historical writing and political purposes are usually inseparable, but a measure of institutional plurality can allow some genuine space for alternative perspectives. Unfortunately, post-independence Indian historical writing came to be dominated by a monolithic political project of progressivism that eventually lost sight of verifiable basic truths. This genre of Indian history and the social sciences more generally reached a nadir, when even its own leftist protagonists ceased to believe in their own apparent goal of promoting social and economic justice. It descended into a crass, self-serving political activism and determination to censor dissenting views challenging their own institutional privileges and intellectual exclusivity. One of the ideological certainties embraced by this coterie of historians has been the imputation of mythical status to an alleged threat of Hindu extremism and its unforgivable complicity in assassinating Mahatma Gandhi.

Historian Dr Koenraad Elst has entered this crucial debate on the murder of the Mahatma with a skilful commentary on the speech of his assassin, Nathuram Godse, to the court that sentenced him to death, the verdict he preferred to imprisonment. Dr Elst takes seriously Nathuram Godse's extensive critique of India's independence struggle, particularly Mahatma Gandhi's role in it and its aftermath, but he points out factual errors and exaggerations. He begins with a felicitous excursion into the antecedent context of the Chitpavan community to which Narhurarn Godse belonged and its important role in the history of Maharashtra as well as modern India. The elucidation of Godse's political testament becomes the methodology adopted by Dr Elsr to engage in a wide ranging and thoughtful discussion of the politics and ideology of India in the immediate decades before Independence and the period after its attainment in 1947.

Godse's lengthy speech to the court highlights the profoundly political nature of his murder of Gandhi. Nathuram Godse surveys the history of India's independence struggle and the role of Mahatma Gandhi and judges it an unmitigated disaster in order to justify Gandhi's assassination. But he murdered him not merely for what he regarded as Gandhi's prior betrayal of India's Hindus, but his likely interference in favour of the izam of Hyderabad whose followers were already violently repressing the Hindu majority he ruled over. In the context of discussing Godse's political testament, many issues studiously ignored or wilfully misrepresented by the dominant genre of lssweftist Indian history writing are subject to withering scrutiny. The impressive achievement of Dr Elst's elegant monograph is to highlight the actual ideological and political cleavages that prompted Mahatma Gandhi's tragic murder by Godse. A refusal to understand its political rationale lends unsustainable credence to the idea that his assassin was motivated by religious fanaticism and little else besides. On the contrary, Nathurarn Godse was a secular nationalist, sharing many of the convictions and prejudices of the dominant independence movement, led by the Congress party. He was steadfastly opposed to religious obscurantism and caste privilege, and sought social and political equality for all Indians in the mould advocated by his mentor, Vinayak Damodar Savarkar (also called Veer Savarkar).

Godse's condemnation for the murder of Mahatma Gandhi cannot detract from the extraordinary cogency of his critique of Gandhi's political strategy throughout the independence struggle and a fundamentally misconceived policy of appeasing Muslims, regardless of long-term consequences. His latter policy merely incited their truculence, and far from eliciting cooperation on a common agenda and national purpose, intensified their separatist tendencies. His perverse support for the Khilafat Movement, opposed by Jinnah himself, was compounded by wilful errors at the Round Table Conference of 1930-32. He took upon himself the task of representing the Congress alone during the second session without adequate preparation, and eagerly espoused the Communal Award of separate electorates. And by conceding the creation of the province of Sindh in 1931 by severing it from the Bombay Presidency, as a result of Jinnah's threats, guaranteed an eventual separatist outcome. Godse also denounced the Congress strategy of first participating in the provincial governments of 1937 without the Muslim League and then withdrawing hastily from them, thereby losing influence over political developments at a critical juncture. He also censures the bad faith of Gandhi's unjust critique of the reformist Arya Samaj and Swami Shraddhananda's social activism and Gandhi's shocking failure to condemn his murder by a Muslim.

Nathuram Godse even espoused the very conclusions of the progressive strand of historical writing in independent India that blamed the British for accentuating communalism (i.e. religious division) to perpetuate imperial rule. What he did oppose was the kind of communal privileges he felt Mahatma Gandhi accorded to Muslims, though in the end he accepted them as unavoidable for the pragmatic reason of eliciting Muslim support for a united, independent India.

Of course, Gandhi's populism transformed both Congress and Muslim politics into a more volatile mass movement. In the case of Muslim politics, over which the constitutionalist Mohammed Ali Jinnah had presided until 1916 before retiring for a time to his legal practice, Gandhi's appeasement helped nurture unequivocal separatism. What Godse implacably opposed was India's partition, which underlined the failure of Gandhi's attempt to appease Muslims. Most of all, Godse was ourraged by Gandhi's continued solicitude towards them after Partition and despite the horrors being experienced by Hindus inside newly-independent Pakistan. In particular, he was appalled by Gandhi's insistence on releasing Pakistan's share of accumulated foreign exchange reserves, which Jawaharlal Nehru also counselled Mahatma Gandhi against, (while India was at war with it in Kashmir), because the funds would immediately aid their war effort.

Revealingly, Godse appears to have grasped the imperative to negotiate wisely with the British in order to achieve the intact legacy of a united India. He was critical of the posturing of the Congress that ended in the disastrously misconceived Quit India Movement of 1942 that was quickly succeeded by Gandhi's total capitulation. The latter could have meant the abandonment of all democratic pretensions and handing over the governance of independent India to the Muslim League to prevent Partition. Quite clearly, Gandhi's assassin was not the raving Hindu lunatic popularly depicted in India, but a thoughtful and intelligent man who was prepared to commit murder. In some respects, Dr Bhimrao Ambedkar was an even fiercer critic of Gandhian appeasement of Muslims, sentiments echoed by no less political giants of India and the Congress like Sri Aurobindo Ghose and Annie Besant.

Dr Elst also provides a brief, but persuasive account of the political lapses of Congress and its iconic personalities, as well as the fate of the Hindu Mahasabha and its prominent leaders, Veer Savarkar and Dr Syama Prasad Mookerjee. He points out the utter folly of Congress politicians in their dealings with British in the 1940s. The highly respected Sri Aurobindo Ghose, a former Congress leader himself, had urged support for Britain's war effort and excoriated Subhas Bose for allying with the Japanese, but to no avail. In addition, Dr Elst carefully highlights Godse's disapproval of the glaring inconsistencies in Gandhi's pacifism, both intellectual and political, counter posing them to the lofty principle of absolute non-violence it supposedly represented. But Dr Elst is fully aware of the tragic impact of the Mahatma's assassination on India and the profoundly debilitating impact it had on Indian nationalist politics subsequently. In his conclusion, he balances Nathuram Godse's critique of Mahatma Gandhi by revisiting its substantial rejection by leading Hindurva scholars, Ram Swarup and Sita Ram Goel. In a lengthy concluding section, he adds his own careful assessment of Gandhi's successes as well as perversity in promoting hostile Islamic and Christian interests. His comments on contemporary Indian political life and the significance of Gandhi's continuing legacy for it are astute.

It is also relevant to reiterate that an important additional contribution of Dr Else's excellent monograph is to underline the insuperable contradictions posed by the Indian discourse on secularism and communalism. In his convincing account, Dr Elst judges that it has turned logic on its head by accusing secular nationalists, represented, for example, by the alleged Hindu nationalists of the RSS, of the very political transgression of communalism that its own support for sectarian privilege, however politically well-meaning, clearly entails. Ironically, Indian politicians of all hues continue to maintain, in a triumph of hope over experience, that true Islam would guarantee Hindu-Muslim amity. And the paradox of independent India is that it evolved into an armed modern entity as secular nationalists like Nathurarn Godse ardently wished.

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi, better known as the Mahatma, was shot dead by the Hindu nationalist journalist Nathuram Godse on 30 January 1948, half a year after the independence and partition of India. During his trial, which ended in a death sentence, Godse was permitted to explain his motives in a speech. The present book is largely a critical comment on that courtroom speech. One of our findings is that while Godse's act was by definition extremist, his criticism of Gandhi was in fact shared by many.

The first version of the present book was De moord op de Mahatma in Dutch (The Murder of the Mahatma'), published by the Davidsfonds in Leuven, Belgium, in January 1998, in time for the assassination's fiftieth anniversary. News of the publication led to my being invited by the leading Dutch radio anchor Marjolein Uitzinger of AVRO broadcasting foundation and by the Dutch Hindu broadcaster OHM- Vtmi for lengthy interviews. By contrast, after initial calls for interviews on the news programmes of Flemish (i.e. Dutch-speaking Belgian) state radio and TV, I was disinvited, apparently because the book did not contain the expected hagiographical indignation over Godse's radical incomprehension of Gandhi's presumed greatness. Its message was not deemed fit for a commemoration of a holy man's martyrdom. Of the two leading Flemish dailies, De Morgen gave it a review mixing praise with indignation, while De Standaard burned it down completely.

At the publisher's request, I had included in the Dutch edition a long introduction of Indian history, the caste system and the Hindu-Muslim conflict. I left these out in the English editions, judging that separate publications on those topics are sufficiently available. The first English edition, Gandhi and Godse: A Review and a Critique, was published in 200 1 by Voice of India, a Delhi-based Hindu publishing house founded and managed by the late great historian, Sita Ram Goel. I had my doubts about having the book published through an ideologically marked publisher, but it seemed there was little alternative. I expected mainstream publishers to be wary of publishing it as it cited most of Godse's speech verbatim, and India's ban on the publication of his speech had never formally been lifted. Like many laws in India, that ban had become dead letter and Godse's own political party, the Hindu Mahasabha, had effectively brought out the speech as a booklet; but a serious publisher with a reputation to uphold might choose to be more prudent. However, when Mr Goel heard of my Dutch book detailing Godse's motives for murdering Gandhi, he himself offered to publish an English translation. He had been a Gandhian activist in his youth and an eyewitness to some of the events discussed in the speech. He always retained a soft corner for the Mahatma, even after narrowly escaping with his life, his wife and his first child during the Muslim League's 'Direct Action Day' in Kolkata, the prelude to the great Partition massacres for which many Hindus and Sikhs hold Gandhi co-responsible. His skepticism vis-a-vis the Hindu nationalists' tendency to blame Gandhi for the Partition is discussed here in chapter 6-8.

A French translation of the Indian edition, Pourquoi j'ai tue Gandhi: Examen et Critique de la Defense de Nathuram Godse (Why I Killed Gandhi: Investigation and Critique of Nathuram Godse's Defense), was prepared at the request of the Paris-based publisher Michel Desgranges in 2007. His prestigious publishing house Les Belles Lettres, otherwise specialized in the Greco-Roman classics, had started a series of books on India directed by Francois Gautier, Indian correspondent for several French dailies. It was a step forward to be published alongside top-ranking Indology scholars like Prof. Michel Angot.

Meanwhile, the English-Indian edition was getting some recognition. It was, after all, a rare entrance into the real thoughts of a Hindu nationalist, as opposed to one of those 'expert' analyses by a biased academic Indologist. Even those Westerners who are in the pocket of the Indian secularists can recognize a reliable source when they are presented with one. That is why Prof. Martha Nussbaum used my book as a source in her own book The Clash Within (Harvard 2007, p. 165 fE, p. 362 ff.). Not that she wrote anything that Nehruvians in India would disapprove of, but at least she got the Godse part right.

A much updated Dutch edition was published by Aspekt Publishers in Soesterberg, the Netherlands, in 2009. It was included in its series of biographies under the simple title Mahatma Gandhi. This amounted to a first-class burial, obscuring the specificity of the book and making it look like just another biography. But at least I am happy it became available in print again for the Dutch- medium public.

Now the book, updated once more, may well have found its definitive shape in this English edition. I thank Professor Gautam Sen for writing an insightful foreword.

| Foreword | ix | |

| Preface | xv | |

| 1 | The Murder of Mahatma Gandhi and Its Consequences | 1 |

| 2 | Nathuram Godse's Background | 12 |

| 3 | Critique of Gandhi's Policies | 39 |

| 4 | Gandhi's Responsibility for the Partition | 74 |

| 5 | Godse's Verdict on Gandhi | 108 |

| 6 | Other Hindu Voices on Gandhi | 136 |

| Conclusion | 171 | |

| Appendix 1: | Sangh Parivar, the Last Gandhians | 176 |

| Appendix 2: | Gandhi in World War II | 184 |

| Appendix 3: | Mahatma Gandhi's Letter to Hitler | 198 |

| Appendix 4: | Learning from Mahatma Gandhi's Mistakes | 215 |

| Appendix 5: | Questioning the Mahatma | 226 |

| Appendix 6: | Gandhi and Mandela | 231 |

| Appendix 7: | Gandhi the Englishman | 234 |

| Bibliography | 241 | |

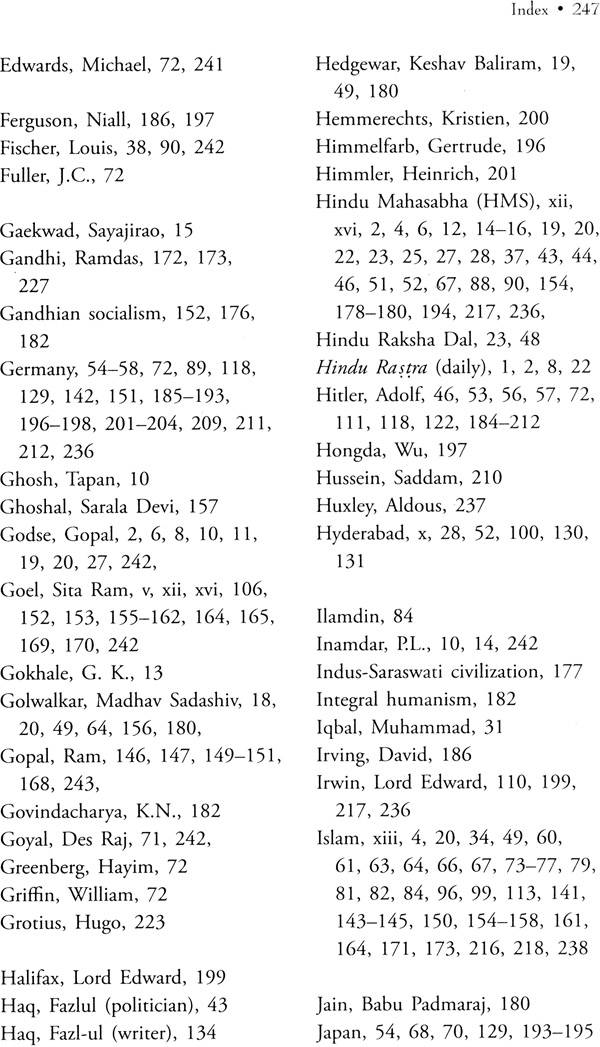

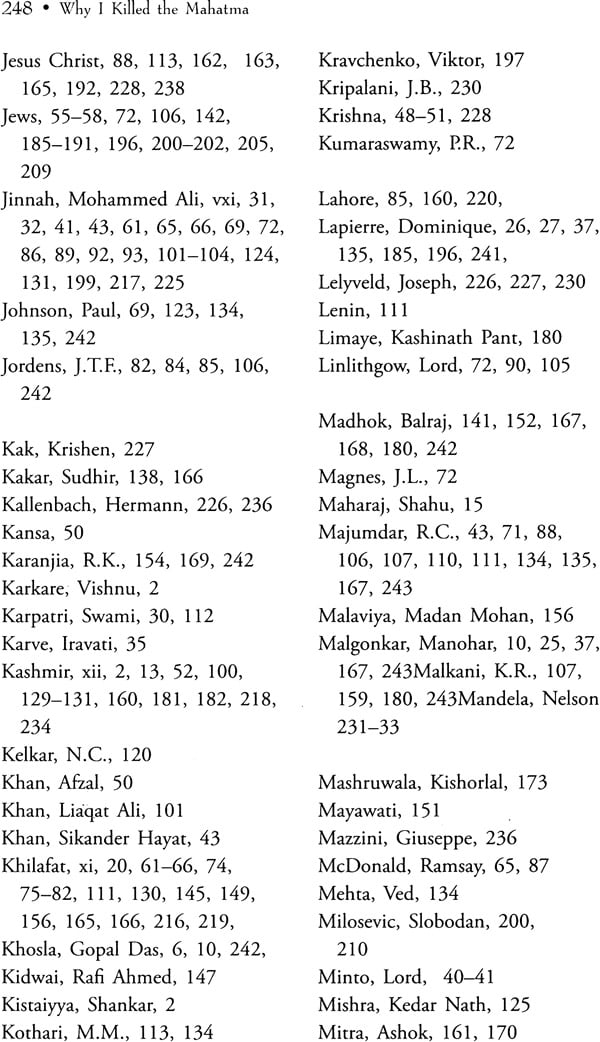

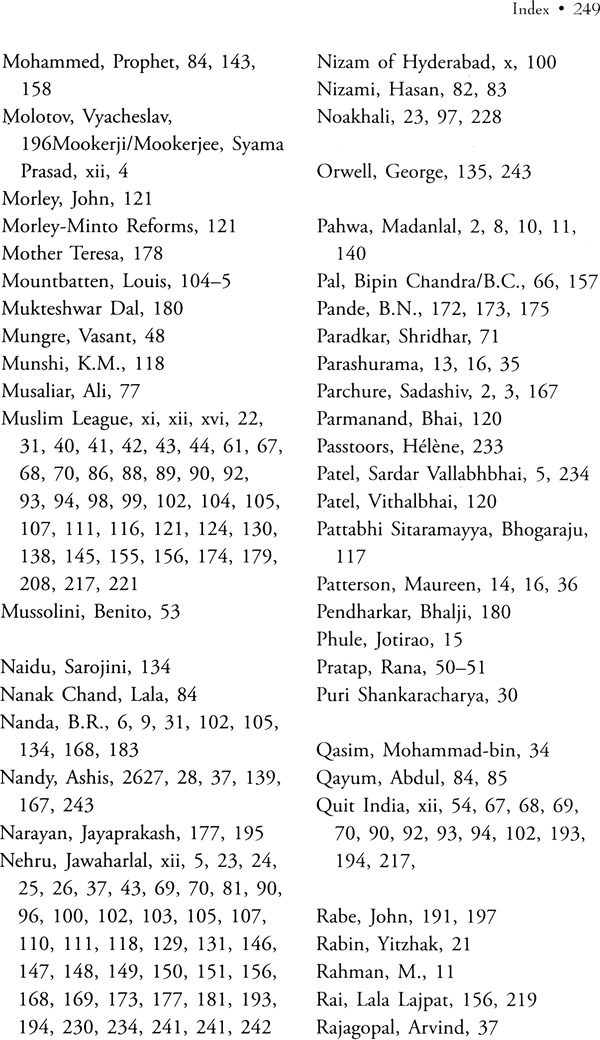

| Index | 245 |