The Yoga of Siddha Tirumular: Essays On the Tirumandiram

Book Specification

| Item Code: | IHL663 |

| Author: | T.N. Ganapathy & KR. Arumugam |

| Publisher: | Babaji’s Kriya Yoga Trust |

| Language: | English |

| Edition: | 2006 |

| ISBN: | 9781895383218 |

| Pages: | 534 |

| Cover: | Paperback |

| Other Details | 8.5 inch X 6.0 inch |

| Weight | 840 gm |

Book Description

Foreword

Thanks to the tireless efforts of M. Govindan of Babaji’s Kriya Yoga and Publications, the Ramakrishna Mission and the late Swami Subramanya of Hawaii, Tirumular is now well known in the West. The present work by T.N. Ganapathy and KR. Arumugam, The Yoga of Siddha Tirumular, ventures to present an in-depth study of Tirumular’s monumental work, the Tirumandiram.

Tradition cherishes it as one of the important Saivite scriptures, Tirumular who can be considered to belong to the 5th Century A.D. believed that the Saivism of his times was not only a religion with a convincing philosophy and Yoga system but that it formed an integral part of our mundane life also.

The Philosophy of the Tirumandiram

After surveying various pramanas or alavais (processes of acquiring valid knowledge), the author of this chapter states that Saiva Siddhanta accepts only three processes (alavais)-perception, inference, and testimony. He has considered in depth the views of Tirumular about God, soul and the world (Pati, pasu and pasa). He explains both the accidental nature and the essential nature of God as delineated in Saiva Siddhanta in the times of Tirumular. He has often quoted the Tirumandiram to explain the following concepts of Saiva Siddhanta: 1. Maya

a. suddha-maya

b. asuddha-maya

2. Karma

3. Anava

4. Nature of the soul

5. States of the soul (stages of consciousness)

6. The soul’s liberation and

7. The nature of the soul in the state of release.

Saivism as Conceived in the Tirumandiram

Tirumular’s philosophy was based on the religious concepts of Saivism, which spoke of the four steps saloka, samipa, sarupa and sayujya in order to reach Siva. The popular myths about it are re-interpreted by Tirumular to explain the metaphysical truths behind them.

The Yoga of the Tirumandiram

The author interprets Yoga as a means by which the basic features of the individual, namely, the physical body, the vital current, mind, consciousness and energy get mobilized and harmonized.

Tirumular has founded a new tradition in Tamil which goes beyond Patanjali’s concept of Yoga. To Tirumular, Siddhas are yogins who practice Siva-Yoga and have attained Siva-jnana. These yogins are called jivan-muktas; jivan-mukti (liberation while living) is a state of embodied wisdom in which the yogin’s attainment transforms all aspects of human life.

The author reveals similarities between the Tantric school of Yoga and the Yoga of Tirumular by analyzing Laya-Yoga. Laya-Yoga is concerned with the functioning of the kundalini, the cosmic power that is inherent in the human body. He considers Laya-Yoga as the highest form of Hatha-Yoga, though its lower stages are now claimed to be Yoga in the Western countries.

The cakra system extolled by Tirumular is an important component of the Laya-Yoga. The author of this chapter has viewed it in the right perspective and appreciates it as one of the subtle operative powers. The cakras are believed to be awakened by the kundalini-the form of the great cosmic power in the individual body. The awakening corresponds to the predominant psychological states and the levels of spiritual consciousness, the aspirant has attained. Kundalini-Yoga is a technique for transforming ordinary consciousness into supreme consciousness.

The function of pranayama (the control of breath and prana) is to awaken the cakras and thus facilitate the rising kundalini through them.

An important element of Tantra-Yoga is the use of mantras and mandalas. The Tirumandiram is a repository of many mantras. The author has given the right explanation to these mantras, the focus being on bija-mantras (the syllable seeds). He defines the bija-mantras as the concentration of the vital force at a point where its sound emitting power gets exhibited.

According to Tirumular, the sphere of the six adharas is classified into three mandalas, agni (fire), Surya (sun) and candra (moon). Tirumular devotes a separate chapter to describe in detail the powers of these mandalas. There is an exclusive discussion in this book on Pariyanga-Yoga of Tirumular. It is called Maithuna-Yoga in which the semen instead of getting ejected is sublimated upwards.

The author considers Pariyanga-Yoga as a type of Yoga in which the heroic yogin and his consort participate inn the great banquet, a secret sex ritual, which culminates in their act of intercourse. It is an expression to show that the yogin’s sensory tumult is stilled, an expression to show that the yogin’s sensory tumult is stilled, paving way for an ever-increasing identity with the cosmic consciousness.

The Mysticism of the Tirumandiram

According to Tirumular, mystical experience is a state of transcendental awareness or a state of oneness. The author analyzes the various levels of consciousness which pertain to Tirumular’s concept of mysticism and mystic experience. Here, the Tamil terms, yoga-samadhi, corugi-k-kidakkum-turai, vettaveli, tungi-k-kanden, etc., are well explained. The five divisions of consciousness according to Tirumular are jagrat, svapna, susupti, turiya and turiyatita. Tirumular considers them as being experienced at five turiyatita. Tirumular considers them as being experienced at five levels-kevala, Madhya-jagrat, suddha, para and a still higher level.

The Twilight Language of the Tirumandiram

The Siddhas usually employ a paradoxical language to describe mystical experiences. The meaning of their poems has to be understood at two levels:

1. The exoteric and the linguistic and

2. The esoteric and the symbolic.

Tirumular too follows the same pattern. The author of this chapter analyzes and classifies the language adopted by Tirumular and identifies more than ten kinds, which are characterized by various kinds of symbols. In one chapter Tirumular has composed all the verses in this twilight language. The author has taken great pains to bring out their hidden meaning.

The Concept of the Human Body in the Tirumandiram

Metamorphosing of the sthula-deha (the ordinary physical body) into divya-deha is called kaya-sadhana. The Tirumandiram specifically assures us that the jiva moves from one body to the other in reincarnation. Kaya-sadhana implies a change of perspective where physical existence is not denied but replaced by a permanent spiritual existence.

When a body is tempered by yogic techniques, one attains the yoga-deha. The ordinary physical body is “burnt out” through continual exposure to the fire of Yoga. For this purpose, the Siddhas have used the following techniques, caga-t-talai, vega-k-kal, poga-p-punal. Saint Ramalingar too has referred to suddha-deha, pranava-deha and jnana-deha.

The Concept of Guru in the Tirumandiram

A guru (spiritual preceptor) to Tirumular is an illuminator who imparts knowledge and helps the disciple glow with spiritual knowledge. A guru is a person who has realized the self (self-realization is the state of the guru becoming Siva Himself). It is a state of unitive experience where there is no distinction between the guru and Siva.

The Social Concern of the Tirumandiram

The Indian thought does not demand of a yogin the renunciation of the world itself. True samnyasa (renunciation) means only the renouncement of desires. Being kind towards other beings (love thy neighbor as thy self) is an important tenet in Tirumular’s spiritual work. Tirumular’s message is:

One the caste

One the God

Thus intense hold

No more death will be.

These lines hint at the highest goal of life, i.e., attainment of the love of God. It is possible only through our loving attitudes towards other beings without any discrimination.

The author classifies the ethical principles of Tirumular into two classes:

1. The ethics which is prior to realization and

2. The ethics which is the result of realization.

Though Tirumular accepted the transitoriness of the body, he knew well its value as an excellent instrument to succeed in one’s spiritual endeavors. Hence, he gives suggestions to enrich the instrument (the body) through observance of medical and ethical principles. He even shows the way for the delivery of defectless birth of progenies. The scope of the Tirumandiram is not only the advancement of the individual, but the welfare of the whole society.

It appears from the epic Mani-megalai that Saivism did not have a great following in Tamil Nadu before the times of Tirumular. Buddhism and Jainism enjoyed greater respect then. Besides Saivism there also existed the Vedic faith, which considered Vedas to be the only object of worship. The scholars were aware of the darsanas -Buta-vata, Samkhya, Nyaya and Upanisads.

Vedantic thoughts could have evolved only after Mani-megalai, which belongs to the third century A.D. The Agamas of Saivism could have been composed in Sanskrit only then. The works in Sanskrit were only based on those in Tamil. These works incorporated yagas and mantras inn a way that suited them. (Refer: P.T. Srinivasa Iyengar, History of the Tamils, chapter on “The Rise of the Agamas.” Also refer: V. Ponniah, The Saiva Siddhanta Theory of Knowledge, p. 7).

Saivism which had the four divisions of carya, kriya, yoga and jnana and included temple worship, rituals, homas (oblations in fire), methods of initiation into religion spiritual practices and the search for ultimate truth could have developed only during this period. Tirumular’s reference to the concept that Vedas and Agamas were different appears to suggest that the Agamas in Sanskrit did not follow the Vedic faith.

There had been many attempts to blend the Vedic faith and the faith of the Tamil people. While Vedas came to be considered the basic and common scriptures, the agamas were viewed as specific works. The Saivites began equating Lord Siva with the ultimate power spoken about in the Upanisads called Brahman. It was believed that the chief God referred to by the Agamas was none other than Siva.

As Tirumular lived during the formative stage of Saivism, his attempts had been chiefly to compile all that had been said about Saivism; explanations are only very brief. The four steps beginning with carya, the four ways beginning with dasa-marga, the two types of liberation-pada-mukti and para-mukti, sakti-nipadam (God’s grace) types of experience etc., have been mentioned as facts and not discussed as the different aspects of Saivite philosophy.

Though Vedic faith and the Tamil people’s faith were coming together in Tirumular’s times, Tirumular categorically points to the separate identity of Tamil faith.

So that I may sing His glory in sweet Tamil.

The lines of Tirumular clearly show his faith in the Tamil religious heritage as well as his aim in life to compose Agamas in Tamil. In fact, the Tirumandiram is the first Agama in Tamil. The stress by Tirumular on the path of love to be the basis of Saivism reinforces the immemorial faith of the Tamil people. Tirumular’s insistence on love can be well inferred from the invocatory verses of the Tirumandiram.

Tirumular states firmly that Yoga cannot be beneficial without love. Combining the Vedic concept of one God and the belief of the Tamil religion that all men are born of the same, Tirumular coins a new concept-One caste and one God.

Yoga is being one with God. A devotee being one with Siva is called Siva-Yoga. In the ascent of the ten steps in spiritual growth (dasa-karya), Siva-Yoga is the ninth step.

To the questions,

1. Who is Siva?

2. Who are we?

3. Are we not different from Siva?

4. Is it possible to be one with Him? etc.

Tirumular affirms that being one with Him is certainly possible. The means to attain Siva is to be conscious of the significance of “One caste and one God.” To know how it is attainable we need to reflect on the following verse:

One the caste; One the God

Thus intense hold,

No more death will be

None other is Refuge, with confidence you can seek

Think of Him and be redeemed,

In your thoughts, holding Him steadfast.

Before analyzing the verse it would be helpful to consider the following:

1. Love and Sivam are not different; Siva is Love. According to Tirumular this a fundamental concept of Yoga. How are we to reconcile this with the concept that Siva is grace personified and that human soul is love-personified?

2. We need to remind ourselves that Siva, who is manifest in all, is manifest in our minds also.

He is the One within, He is the light within

He moves not a wee bit from within

He and your heart are thus together

But the heart His Form knows not.

How are we to identify the hidden Siva in us? There are quite a few ways. An inkling of Siva is possible in nature’s beauty, in music, in sounds of mantras and in mystic experiences.

Tirumular feels that the ability to consider others as oneself, service to society and being charitable can also facilitate our efforts to be one with Siva. This is suggested by the above reference that there is only one caste and one God.

Living beings are innumerable and men have been classified into many castes. However, there is no real difference among them. Their intelligence, talents and qualifications may vary; in aliveness and love, there is no place for difference. Further, there is ground to unite all the beings for it is the same God who manifests in all. God being One, there can be only one caste, according to Tirumular.

Tirumular has well blended his knowledge obtained by yogic practice, the knowledge of other Siva-yogins as well as the facts from the Upanisads and Agamas to offer us what he calls Vedanta-Siddhanta faith. His work Sadasiva Agama is only a book on the faith of wisdom, as wisdom is the consequence of reflections about feelings and experiences, the stages of it (wisdom) get stated first.

Yogic practice causes vibrations all over the body. It enables us to experience the vibration from the waist (muladhara) to the scalp (sahasrara). It is averred that this vibration goes twelve inches above the scalp. During the course of such experience, visualizing a light in between the brows and at the top of the head are considered the best. The spirit (jiva) in us is supposed to grow by such experiences.

This (same) spirit is called jiva, when it resides within the body and called soul (atman), once it is out of it. The significance of Siva-Yoga is that it helps life (the spirit within) attain wisdom, joy and oneness with Siva even while alive.

I was really elated to write a Foreword to this important work. This is the first work to present a comprehensive and clear explanation of the contents of the Tirumandiram for the reader of the English language.

Back of the Book

“The Yoga of Siddha Tirumular: Essays on the Tirumandiram”

This book fulfills a longtime need for a comprehensive introduction and commentary in the English language for one of Yoga’s greatest source works: the Tirumandiram or “Holy Garland of Mantras,” described by Dr. Georg Feuerstein Ph.D “as important as the Yoga-Sutras of Patanjali, the Bhagavad Gita and the Yoga-Vashistha combined.” Tirumandiram is considered to be the greatest and earliest seminal work of the Siddhas, the greatest adepts of Yoga, and an encyclopedia of philosophical and spiritual wisdom rendered in verse form. It is a book of Yoga, tantra, alchemy, mysticism, mantra, Yantra and philosophy. But without a commentary, it has been difficult for most English readers, unfamiliar with much of its underlying philosophical concepts, to clearly understand.

This new book explain clearly the most important themes and philosophical concepts which are woven throughout the Tirumandiram. These include” Saivism; the nature of Siva and the relationship which the soul or jiva has with the Lord; the philosophical school of Saiva Siddhantha; the concepts of God, the soul, the world, liberation, the paths to liberation; the bonds or impurities which keep the soul in bondage; the concept of Grace; Love; meditation; jnana; the Yoga of Tirumandiram: Astanga-Yoga, Khecari-yoga, Pariyana-Yoga (tantric yoga), Chandra-Yoga (literally “moon” yoga), Kundalini-Yoga; mysticism, the concept of the human body and its transformation into a divine body; the concept of the guru; the social concerns of the Tirumular. With an understanding of the basic ideas, the reader will then be stimulated to make a detailed study of the Tirumandiram itself.

It is the sixth publication in a series produced by scholars of the Yoga Siddha Research Center, in Chennai, South India, sponsored by Babaji’s Kriya Yoga Order of Acharyas and the Yoga Research and Education Center. The present work benefits from the great familiarity which the authors have developed over many years of full time study of much of the massive body of palm leaf manuscripts written by the Siddhas.

| Foreword | v | |

| Suba. Annamalai | ||

| Preface | ||

| T.N. Ganapathy | ||

| GUIDE TO PRONUNCIATION IN TAMIL | xxv | |

| Chapter 1 | Introduction KR. Arumugam | 1 |

| Chapter 2 | The Philosophy of The Tirumandiram KR. Arumugam | 43 |

| Chapter 3 | Saivism As Conceived In The Tirumandiram KR. Arumugam | 97 |

| Chapter 4 | The Yoga Of The Tirumandiram T.N. Ganapathy | 147 |

| Chapter 5 | The Mysticism of the Tirumandiram T.N. Ganapathy | 231 |

| Chapter 6 | The Twilight Language of the Tirumandiram T.N. Ganapathy | 279 |

| Chapter 7 | The Concept of the Human Body in The Tirumandiram T.N. Ganapathy | 323 |

| Chapter 8 | The Concept of Guru in the Tirumandiram T.N. Ganapathy | 365 |

| Chapter 9 | The Social Concern of the Tirumandiram KR. Arumugam | 401 |

| Chapter 10 | Conclusion T.N. Ganapathy | 439 |

| Appendices | ||

| Appendix-A | The Works That Unduly Claim the Authorship of Tirumular | 445 |

| Appendix-B | The Categories of Souls | 449 |

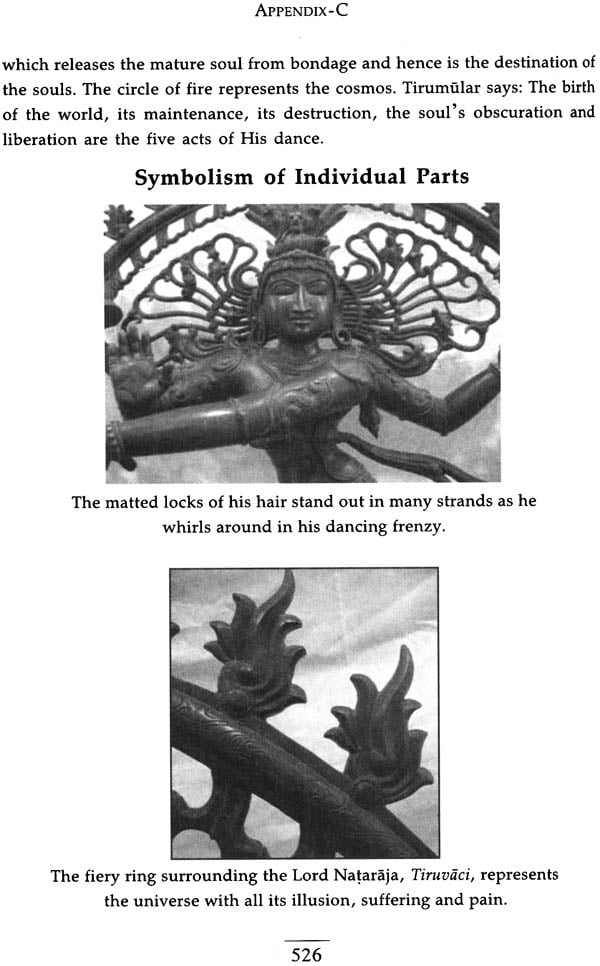

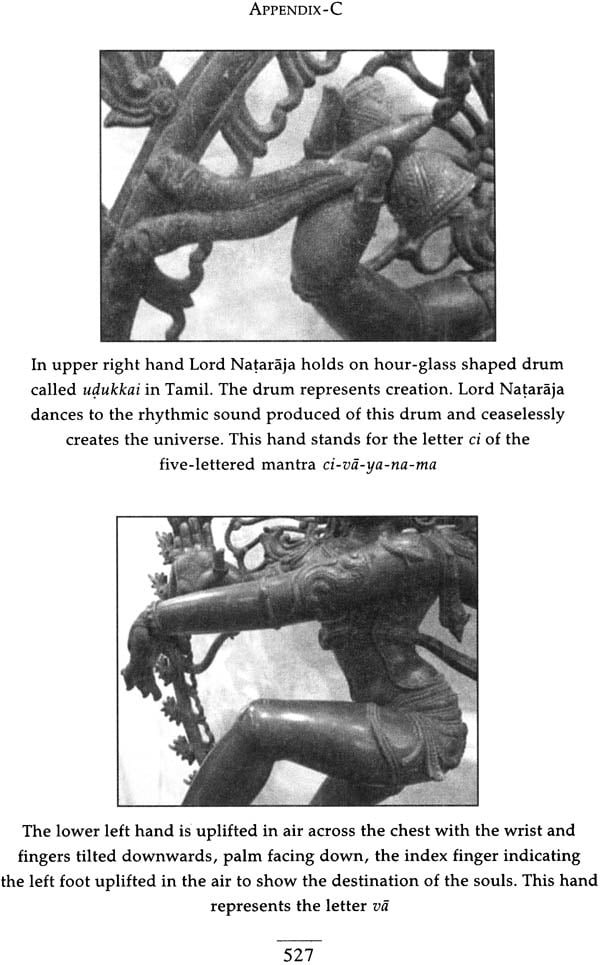

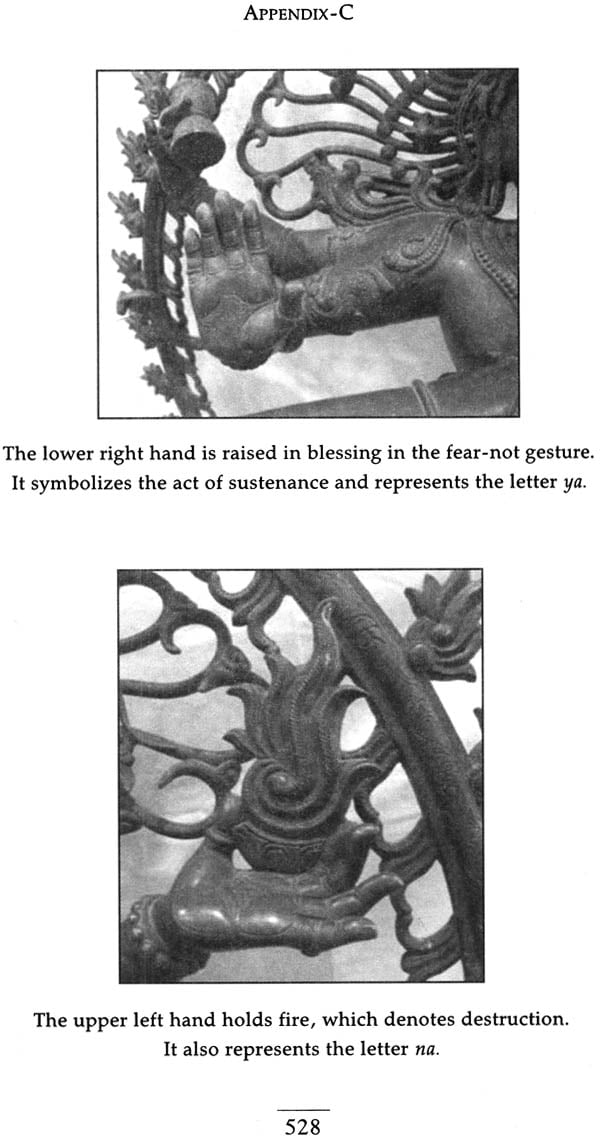

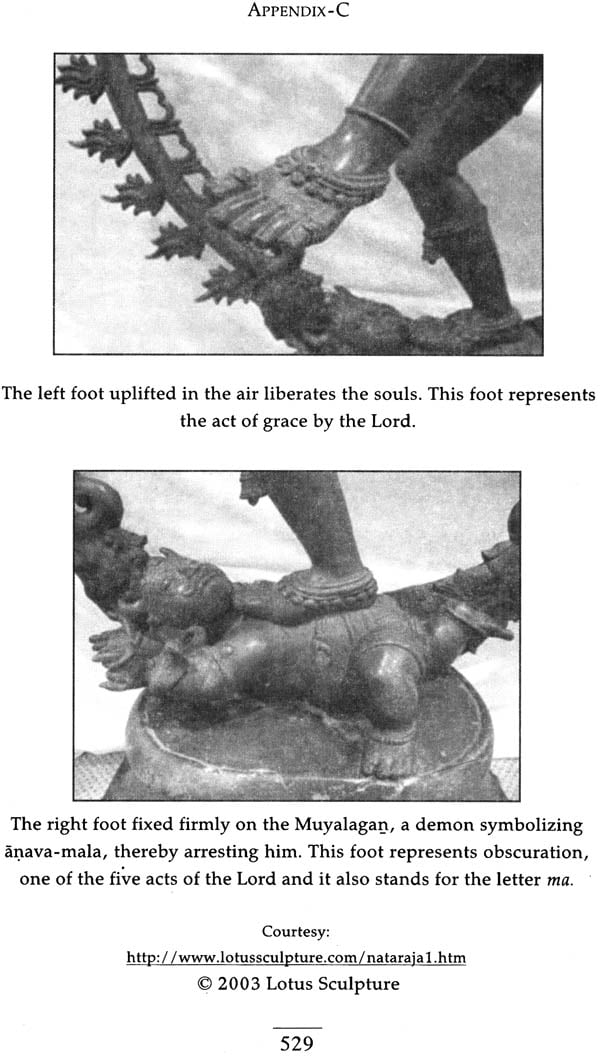

| Appendix-C | The Symbolism of the Dance of Siva | 451 |

| Appendix-D | A Brief Discussion of the Five ‘M’s: Panca-Makara | 457 |

| Appendix-E | The Pariyanga-Yoga | 463 |

| Appendix-F | The Thirty-Six Tativas | 473 |

| Appendix-G | The Twilight Terms That Occur in the Tirumandiram | 477 |

| Bibliography | 483 | |

| Index | 497 | |

| About the Authors | 533 |